Barclay James Harvest: the British pioneers who led prog to glory

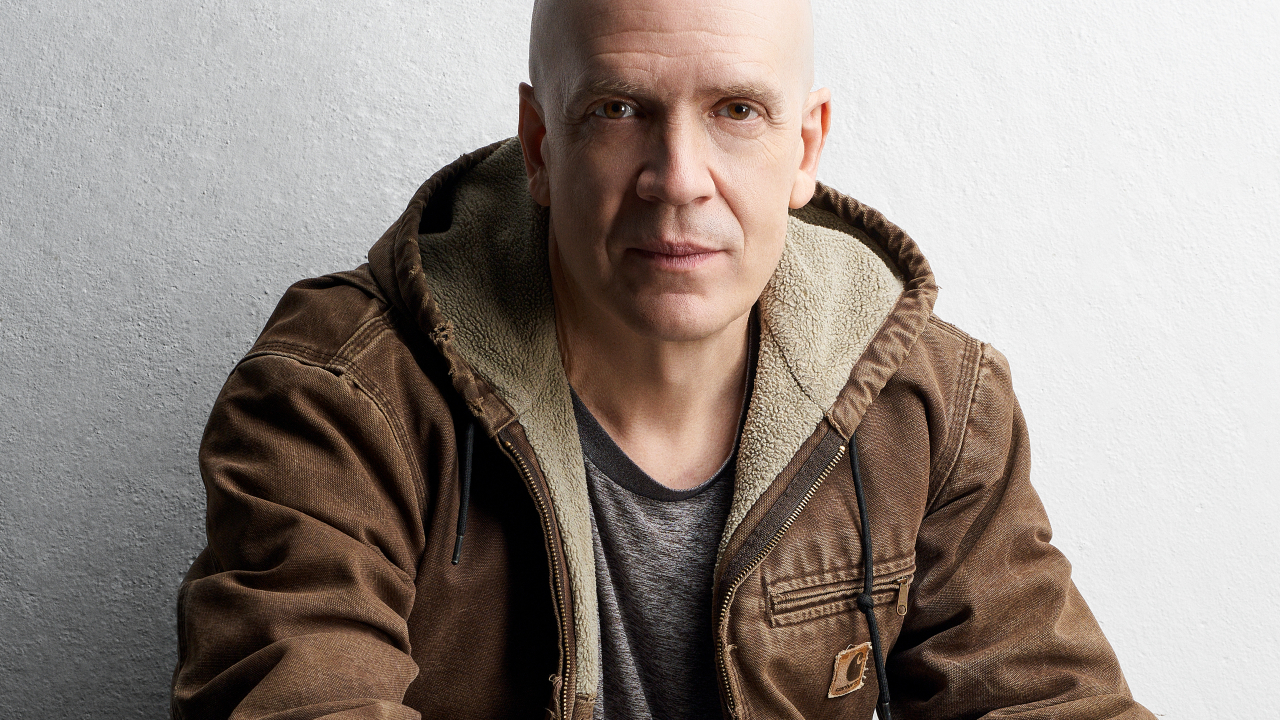

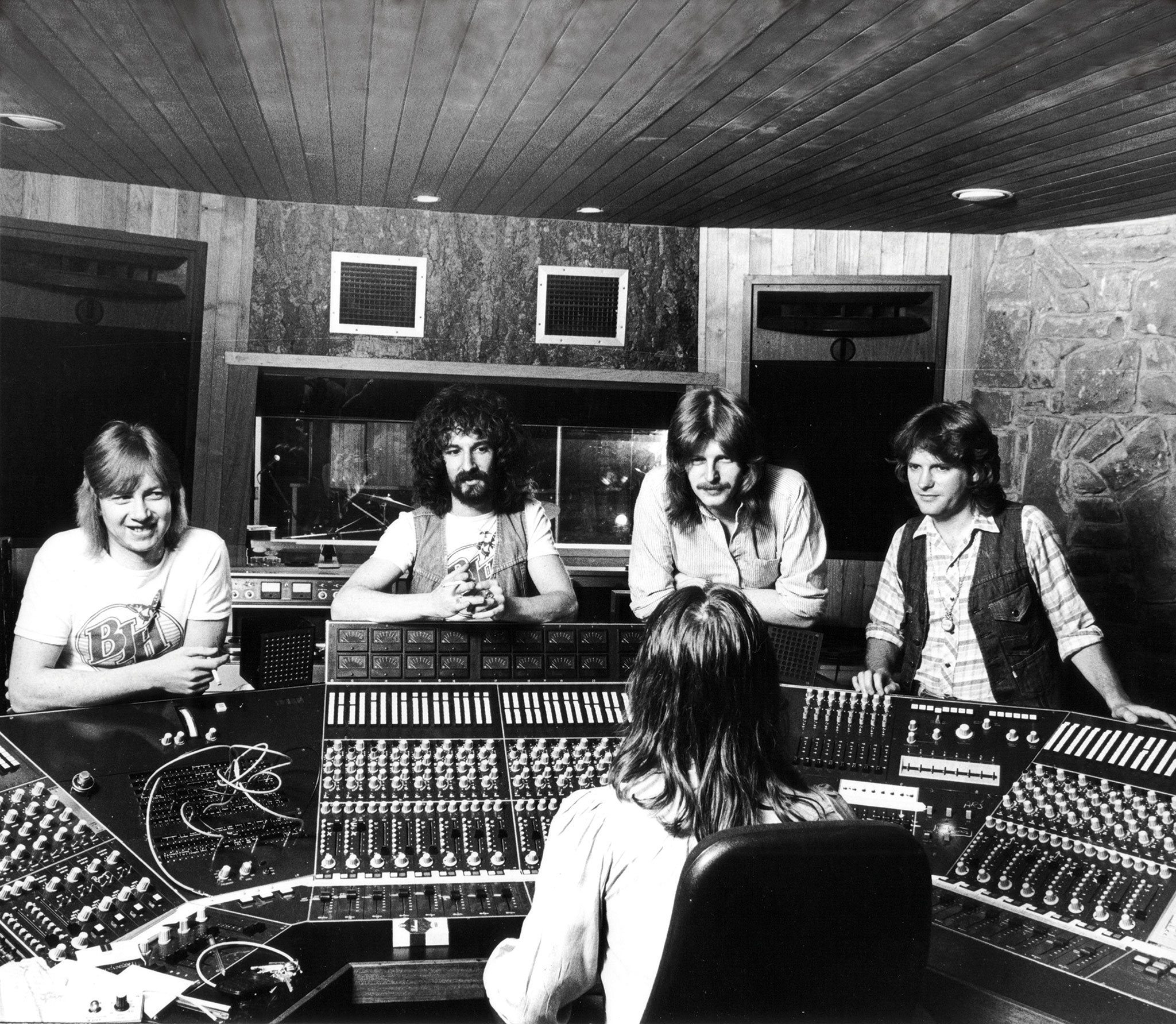

Multimillion-selling albums, sold-out UK tours and legendary status in, er, Germany: John Lees reveals how Barclay James Harvest spearheaded the prog scene

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“I don’t think people realise how far back Barclay James Harvest goes,” says guitarist and vocalist John Lees. “We played Middle Earth at the Roundhouse in 1968 with The Gun, and with Pink Floyd at London All Saints; with Genesis and Led Zeppelin, Pink Fairies, Edgar Broughton, that kind of heritage.”

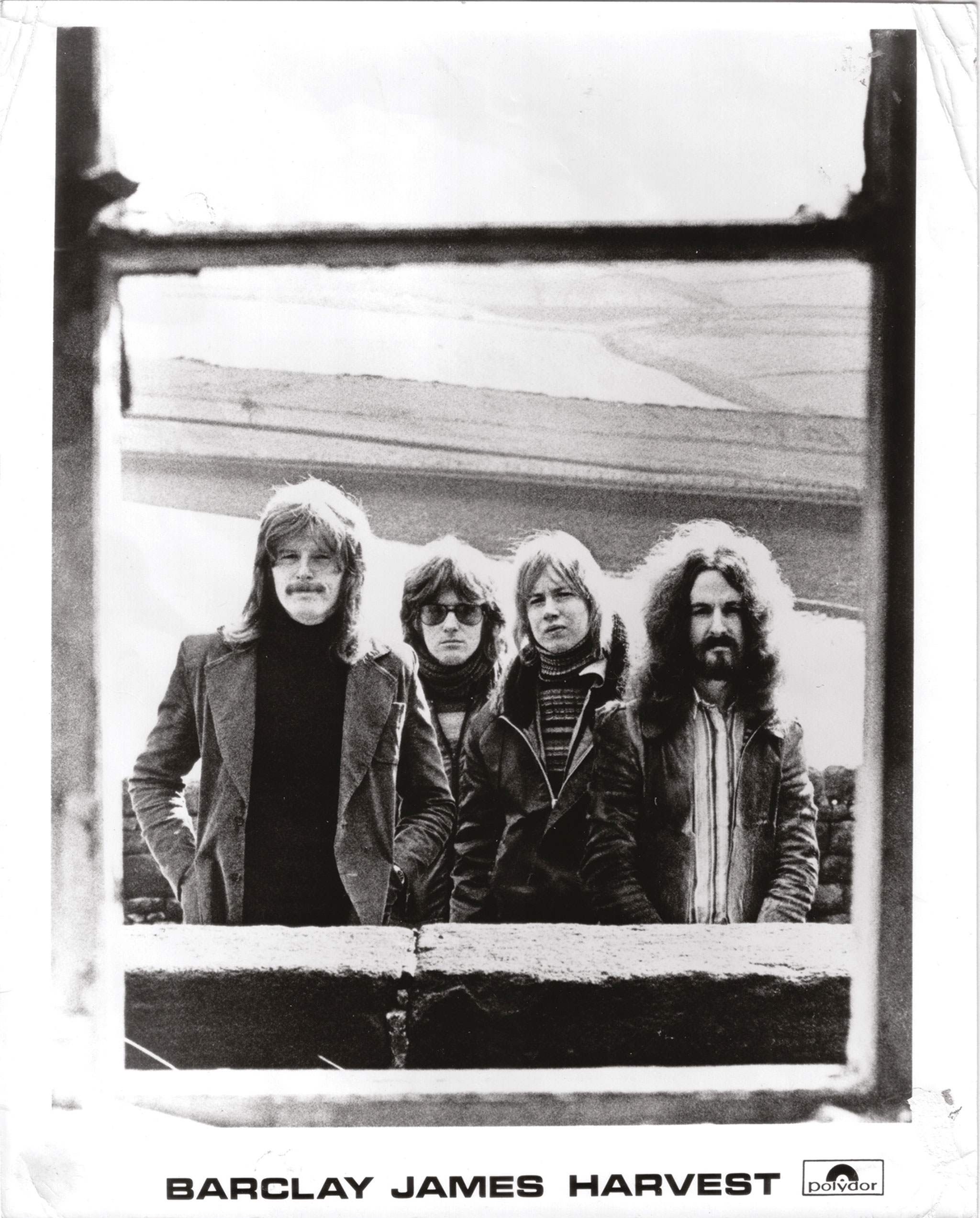

Lees is right, of course, as many associate the group with their 70s heyday. Esoteric are re-releasing two defining albums from that decade, Everyone Is Everybody Else (1974) and Gone To Earth (1977), but the story started in Oldham in 1967 when two blues groups joined together to form Barclay James Harvest.

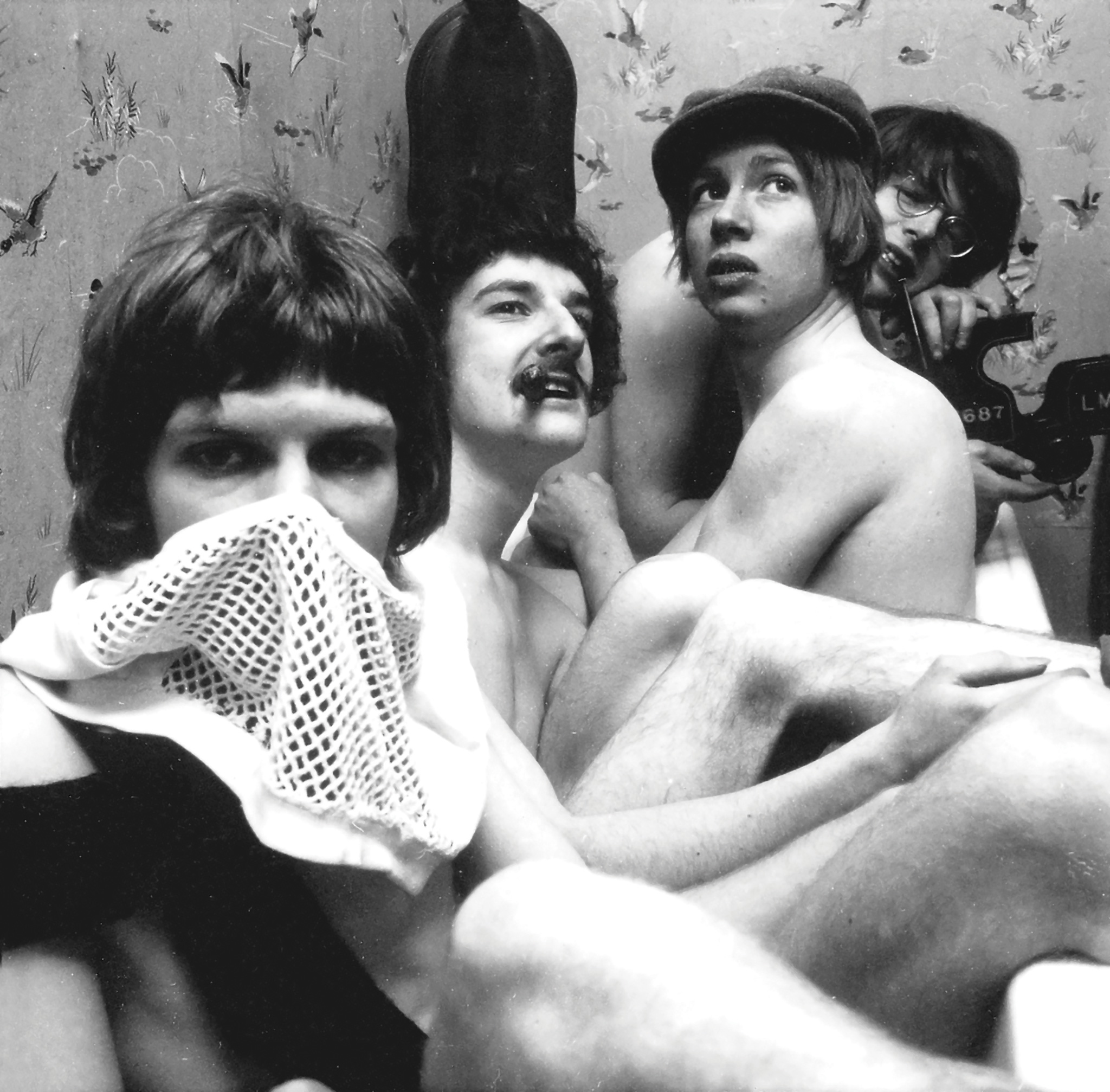

The ambitious group attracted an early patron in local fashion entrepreneur John Crowther, who had bought Preston House, a semi-derelict farmhouse in nearby Diggle, into which the group moved en masse. “We all more or less quit our jobs and threw holiday pay and final pay into a pot, and with his help we were going to write the hit single,” Lees recalls.

Article continues below

Crowther hawked a demo tape around record companies and the band were briefly signed to Parlophone, then moved to EMI’s new progressive subsidiary, Harvest, whose name was suggested by the group.

Initially they played in a melodic, folky style and experimented with chamber ensemble instrumentation such as tenor horn, oboe, recorder and cello, both in the studio and onstage. “We were looking for something very different,” says Lees.

They had come across a mellotron at Abbey Road Studios that Woolly Wolstenholme played on 1968’s Early Morning, their debut single for Parlophone, and they hired one from a keyboard shop in Derby – the first time it had left the shop. They eventually bought it, and it became a hallmark of their sound.

But in the questing spirit of the era, the band were determined to work with an orchestra. They had met up with Robert John Godfrey, who worked for the group’s agents, Blackhill Enterprises. Godfrey orchestrated some of the songs on Barclay James Harvest (1970) and Once Again (1971), and they also worked with orchestral leader and orchestrator Martyn Ford.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

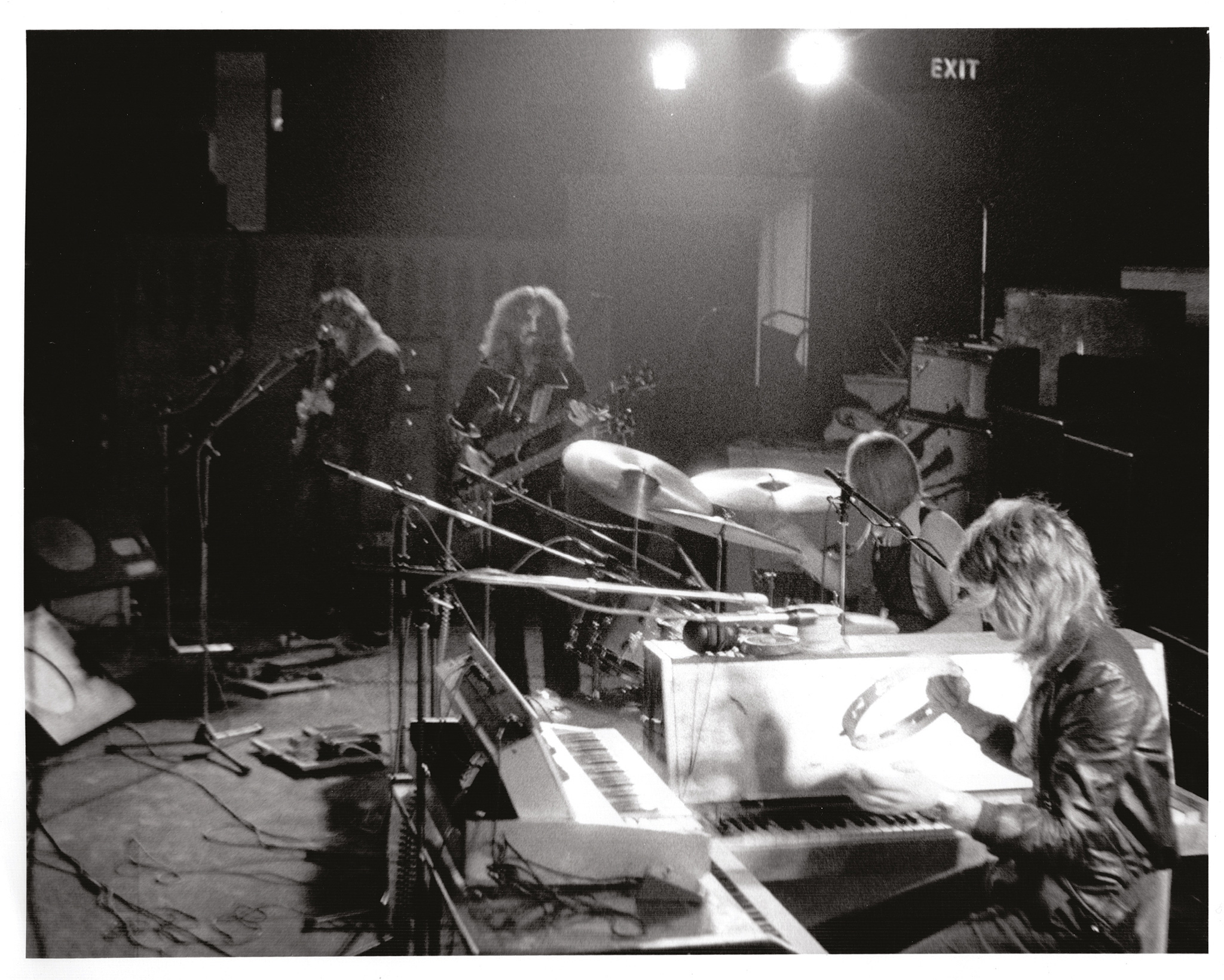

Barclay James Harvest were one of the first rock groups to tour with an orchestra, from early 1971, but things weren’t as grand as they might have appeared. “It was a disaster,” say Lees. “It was a [London-based] student orchestra who were hard to work with. We needed to pay for extra rehearsals when they weren’t up to speed, because what we were doing was groundbreaking at the time, marrying a rock band to an orchestra.”

Lees recalls that their budget dictated that the orchestra would get smaller as they played further away from London. The venture practically bankrupted John Crowther, souring their relationship, but it had its benefits.

“It probably made the group, because then we had to pay for it all and that meant gigging for as many days as we could, every week for a year and a half to two years, doing universities, clubs and colleges,” Lees explains. “And that gave us a name and really cemented our career.”

By Everyone Is Everybody Else, released in 1974, the hard-working group had developed into a tougher proposition, with dramatic, anthemic songs fuelled by Lees’ incisive rhythm guitar and keening lead lines, cut with vocal harmonies along the lines of Crosby, Stills And Nash, particularly on bass guitarist Les Holroyd’s Poor Boy Blues.

Barclay James Harvest were virtually unique in progressive rock in that their songs were full of social commentary and even politics. “I’m fortunate in that I can explore my anxieties and fears in songs, but there was always a caveat with me that I don’t really want to ram it down anybody’s throat: if you get the lyrics, then great. If not, it still stands up as a song.”

Lees’ The Great 1974 Mining Disaster references the Bee Gees’ 1967 single New York Mining Disaster 1941, updating it to reflect the miners’ strike that brought down Edward Heath’s government. Holroyd’s Negative Earth is a tale of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission set to a swooning melody, while Lees’ Child Of The Universe and For No One are statements against war and for peace and universality.

Half of the songs on Everyone Is Everybody Else fed into the double album Barclay James Harvest Live, released in 1974, which took many by surprise as it showed that in concert, they were one of the most powerful progressive groups in the UK, their songs elongated and swelling into huge choruses, all powered by Mel Pritchard’s spectacular drumming. It was their first UK chart success, breaking into the Top 20.

Despite “selling out gigs for fun”, the physical size of the PA, the lights and the road crew meant they were only breaking even at the end of UK tours. “That’s one of the reasons we went into Europe, where you could get more bums on seats and justify the cost of the show,” says Lees.

Barclay James Harvest released their eighth studio album, Gone To Earth, in 1977. How does Lees feel they had progressed musically over the decade since forming? “I think it was a great learning curve through the whole of that era,” he says. “Take Hymn. We are producing, from a simple beginning, this huge, climactic number, with what appear to be massive brass and strings, which was in fact just us using synthesizers, mellotron and guitars. Sea Of Tranquility was an orchestral thing Woolly had done, so there’s quite a level of sophistication creeping into the arrangements when you get to Gone To Earth.”

Lees continued his rather cheeky rearrangement of songs with Poor Man’s Moody Blues. Written after a snide music paper review of the group, it’s a pastiche of The Moody Blues’ Nights In White Satin. “I wish I hadn’t penned it – it’s haunted me ever since,” admits Lees. “It might sound similar, but musically it’s not the same at all. The Greeks use it as a wedding song. When they have the first dance, they play Poor Man’s Moody Blues. How that figures, I do not know.”

As Barclay James Harvest began to play more in Germany, that country’s audience formed a peculiarly strong bond with the group. They became massive there, and while Gone To Earth reached No.30 in the UK charts, in Germany it peaked at No.10 and stayed in the album charts for 197 weeks. As of 2011, it was ranked No.6 in the list of albums that have spent the most time in the German charts.

“On one of the later tours we did in Germany, in 1979-’80, we sold a million tickets,” says Lees. “It’s ridiculous! I’ve got a platinum ticket at home. Then we went on and played to 185,000 people in front of the Reichstag.”

Barclay James Harvest may have never had the hit single they wanted at the outset, but they’ve more than made up for that with album sales. “We’d sold something like seven million albums back in the late 70s – I hate to think of how many we’ve sold now,” laughs Lees. “It’s fantastic really. We’ve just always had massive support.”

The remastered and expanded edition of Everyone Is Everybody Else is out now, while Gone To Earth is out on September 2, both on Esoteric.

Exclusive interview with Barclay James Harvest founder Les Holroyd

Barclay James Harvest - Everyone Is Everybody Else album review

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.