Gazpacho On time travel and the end of the universe

The ninth release from Norwegian deep-thinkers Gazpacho is a concept album like no other, and it may just be the most explosive record ever made...

Warning: if you listen to Gazpacho’s new album Molok on a CD player, there is, theoretically, a chance you might just cause the end of the universe as we know it. No pressure, then.

The physics behind such an outlandish claim is complex; just as complex as the record’s deep, thought-provoking concept that delves into the idea of humanity being devoid of real meaning in the absence of a god figure.

With all the fantasy behind the record – the Norwegian sextet’s ninth since forming in 1996 – it’s a little easy to forget about the music, which spans nine songs and meanders through a variety of styles, from haunting art rock to electronica, jazz folk to gospel. It continues Gazpacho’s trend, exhibited on previous albums such as 2007’s Night, of concocting immersive music that isn’t just a simple listen – it’s a journey, a passage through the cerebral vortex and back.

We’re trying to make an artistic point. If the universe can be destroyed, then that means the universe is a mechanical place. According to that, you’re just a chemical reaction.

The Oslo group’s last record, Demon, only hit the shelves in 2014, with the band almost mimicking the conveyor-belt turnover rate of mainstream pop’s big hitters. Molok, however, wasn’t a case of pushing out a release that had been swiftly mashed together to appease record-label suits.

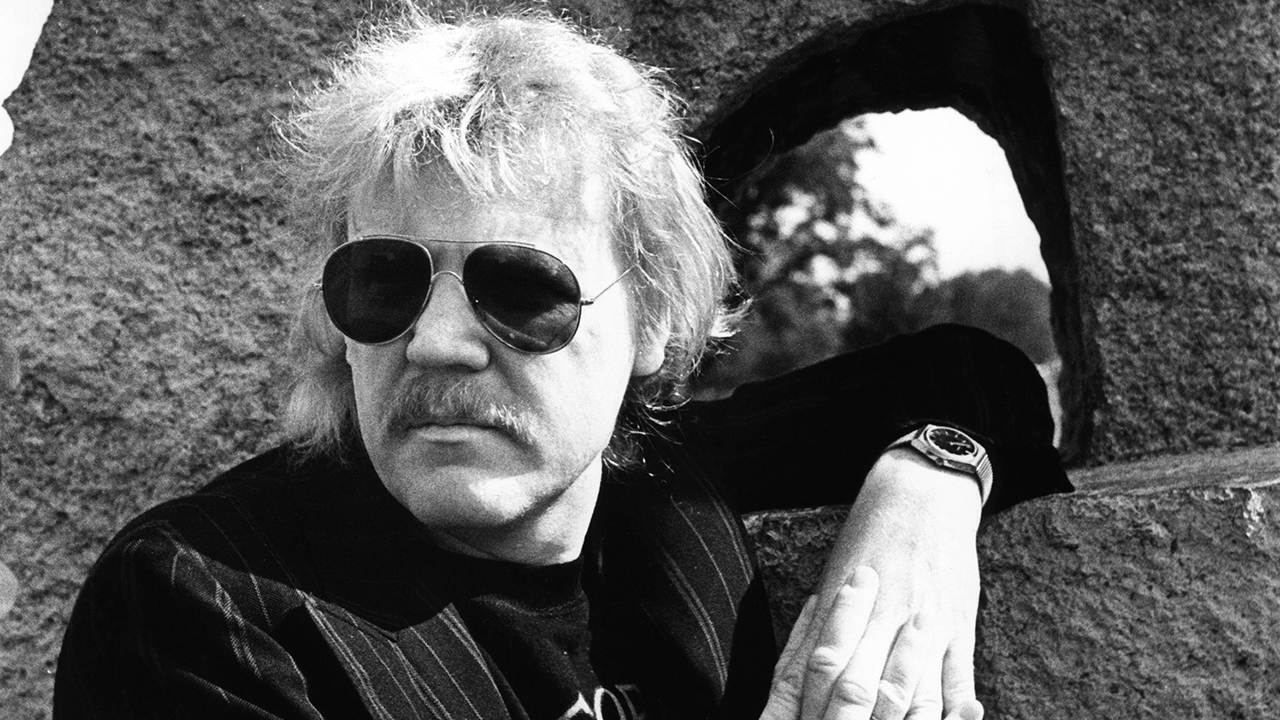

“I’m opposed to releasing music just for the sake of releasing music,” says keyboardist and principal songwriter Thomas Andersen. “I’ve always said that with all the music being produced these days, you need one hell of a good excuse to make an album. If you’re going to ask for someone to spend 45 minutes of their life listening to your stuff, you need a very concrete message.”

That message this time around, says Andersen, centres on “the origin of the responsibility of your actions and morals and the origin and banality of evil”.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The story of the album, in very basic terms, focuses on the time machine Molok, which comes to life on the winter solstice. With loose laws of physics at play, the machine manages to simulate the past, trying to find evidence of a god. There’s a plethora of themes, such as the meaning of life, faith, morality and, importantly, how many religions appear to worship stone.

“It seems like God has been chased into the stone, never to return,” Andersen says. “And for this reason, the man in the story decides the universe is a mechanistic place.”

“If [the universe’s creation] was just the big bang, which it was,” adds singer Jan-Henrik Ohme, “then that could be reversed. If that happened, a lot of sense and meaning and religion would be a waste, and it has been for as long as mankind has existed.”

It’s these thoughts that bring us back to the suggestion that you could kill off billions of people by pressing ‘play’ on your Molok CD. It all stems from an innocuous bleep at the finale of closing track Molok Rising, which should cause correction software on CD players to generate a number. If that number corresponds with the position of all the electrons whizzing around in the world at that very moment, then, technically, the universe could stop. University physicists have backed up the mind-boggling theory.

The noise replicates the moment in the story when the Molok machine – “by accident or by its own choice” – does the same thing and destroys the universe. Don’t get too worried, though. “That happening would be like winning the lottery a billion times over without participating in it,” Andersen reassures Prog. “We’re trying to make an artistic point. If the universe can be destroyed, then that means the universe is a mechanical place. According to that, you’re just a chemical reaction.

“If we’re just very advanced machines, then the moral aspect of destroying us is something which we need to question, because what’s wrong with destroying a machine? If we remove God, we have to replace morality with something else.”

Andersen is a big thinker, and he apologises more than once for “rambling”. But where does the inspiration come from? He thinks, on a subconscious level, that a heartbreaking turn of events in his personal life may have seeped into the new record.

“I lost both my parents last year, and the next album we make after that is based on the idea of God’s death? A psychologist must think there has to be something in there. When we remove God from the equation, we are the masters of the universe, or at least the masters of Earth, and there’s huge responsibility that comes with that.”

Molok, which was created in and around Oslo, grabs the Gazpacho style – lush soundscapes mixed with outward-looking art rock – but slathers it with a more barren yet wholly captivating aura that’s part Porcupine Tree, part Anathema.

“Its starkness is a deliberate move,” says Andersen. “On this album we decided that our usual sound might not be correct for the concept as there is an idea that the machine Molok itself is making some of the sound.”

Gazpacho drafted in Daniel Bergstrand to mix Molok, who has previously worked with metallers Behemoth and Dimmu Borgir.

“He was very into making the sound mechanical in a magical way, and he has a knack for creating spaces using reverbs. We also have a tendency to think very much like classical musicians when we write, where nuances in chords are important to generate different feels to the melodies. The hard production is a great contrast to us being the picky, obsessed-with-every-detail types that we are.”

Norwegian music archaeologist Gjermund Kolltveit also makes an appearance to play representations of age-old instruments, as well as a local singing stone that may have been used 10,000 years ago.

It’s fair to say, knee-deep in concept, that this album’s prog credentials are pretty resolute. However, for some band members, that might be a little bit of a dirty word.

I lost both my parents last year, and the next album we make after that is based on the idea of God’s death? A psychologist must think there has to be something in there.

“I think we’re progressive in that we’re dabbling in different genres and we try our best not to be derivative,” says Ohme. “We’re trying to make it different in that way, and if different means progressive then yes, we are progressive. But I take much more pride in when we get called art rock. I think that’s more of what we’re trying to do.”

Fellow founding member Andersen, however, seems to welcome the ‘P’ word more. “I grew up and still am a big fan of progressive rock,” he says. “I love Kate Bush, and I think Hounds Of Love is the best album ever made. There is no doubt in my mind that it’s a progressive rock album. And I love Jethro Tull and Yes and Genesis and Marillion.

“I have no problem being prog rock, but I think the idea of prog is that it should be progressive. I am a little wary of bands now who are trying to emulate the sounds of the old masters of the 1970s. It should be more about trying to create new music that hasn’t been heard before.”

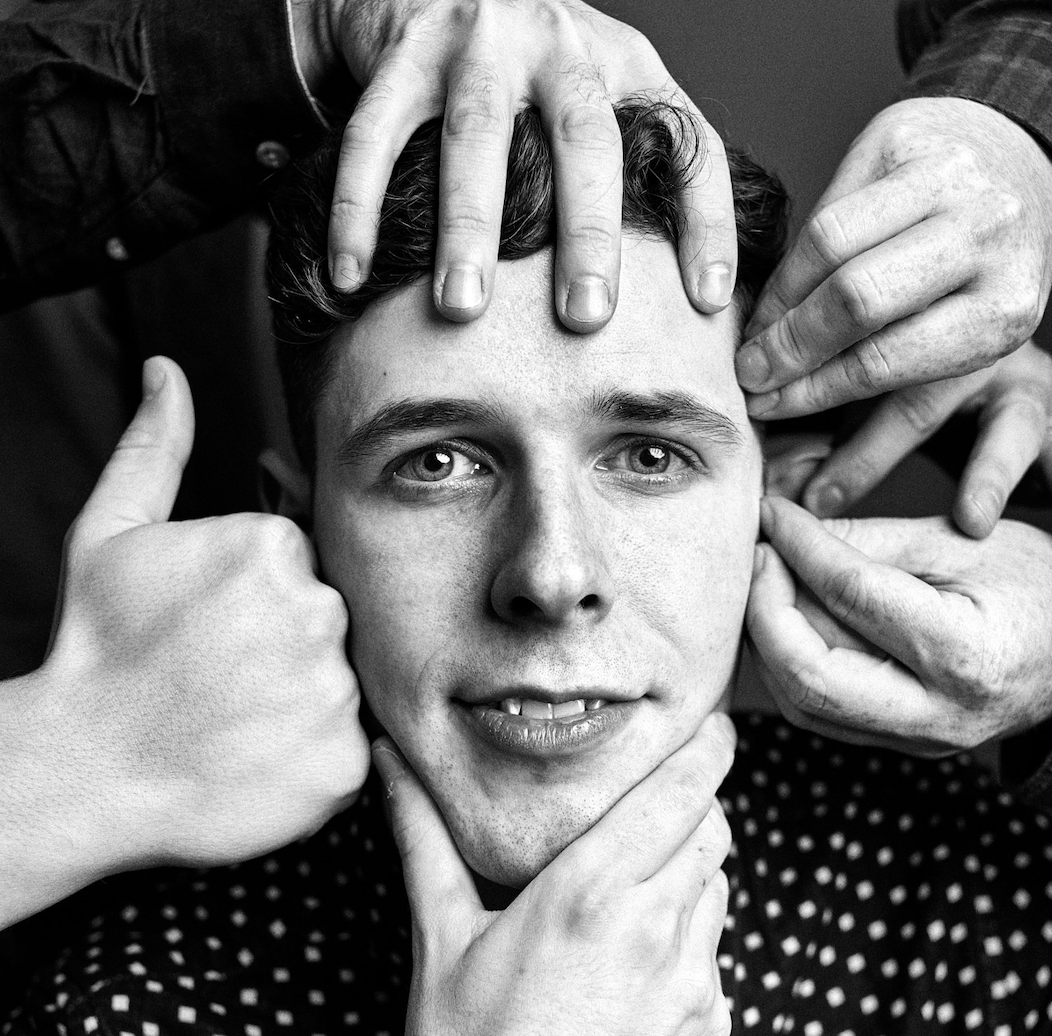

Gazpacho – named after the Marillion song and not so much the cold soup – have steadily evolved since forming in the mid-1990s, with Andersen and Ohme joined by guitarist Jon-Arne Vilbo as core members. They’ve now got violinist Mikael Krømer, bassist Kristian Torp and drummer Lars Erik Asp in on the action too, forming a tightly knit sextet of free-thinking musicians.

Despite continuing on their upwards trajectory, though, it seems that touring reluctantly will remain something of a rare treat. Ohme is a high flier at Sony Music in Norway, while Andersen runs a studio in Oslo, as well as creating advertising jingles – something he has been doing for two decades. “You’ll hear some of my stuff during every single commercial break on the radio,” he says.

The others, meanwhile, work in areas such as pharmaceuticals and computer engineering.

“Most of us are in our early 40s and you have obligations that are very hard to get around,” Ohme says. “Some of us have senior positions – you work your ass to bone, as they say. You have four or five weeks’ holiday, and taking two of those for touring is not very popular. It’s getting harder and harder. But it’s still just as fun making music and recording it, and playing the few concerts we do.”

After putting the grand, overarching Molok in the can, you might think that Gazpacho would be concepted out, weary of such deep thought for at least a couple of years. Think again. “Thomas and I have said if the next album takes four years then it takes four years,” Ohme reveals. “But if it takes four months then it takes four months. We’ve already talked about at least four new concepts for the next album.”

Only time will tell, it seems, if Gazpacho will continue their prolific streak with another absorbing record in quick succession. If the world hasn’t ended by then, that is…

Molok is out now on Kscope. For more information, see www.gazpachoworld.com.

A writer for Prog magazine since 2014, armed with a particular taste for the darker side of rock. The dayjob is local news, so writing about the music on the side keeps things exciting - especially when Chris is based in the wild norths of Scotland. Previous bylines include national newspapers and magazines.