Time For Livin': How Check Your Head brought Beastie Boys back from the dead

Released on April 21, 1992, the kaleidoscopic, irreverent Check Your Head saw the Beastie Boys tap into their punk roots, silence haters and become kings of their own ultra-cool universe

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

On March 15 1992, the Beastie Boys stepped onto a London stage for the first time in five years. Appearing at the latest iteration of the Marquee club, located on Charing Cross Road, the New Yorkers’ svelte headline set – barely 50-minutes, no encore – was notable for more than one reason.

The most casual of observers would have noted a reduction in the band's circumstances. Back in 1987, the trio’s co-headline UK tour with fellow New Yorkers Run DMC was the kind of affair about which the entire nation had a view. Subjected to the sincerest compliment in the vast arsenal of the domestic tabloid press – the moral panic – the hit-job on these unsuspecting Americans was such that questions were raised in the House of Commons regarding their suitability for the eyes and ears of Britain’s youth. Never mind that the tizzy made no sense at all – it was good for business. That May, the Beastie Boys performed for more than 12,000 rap fans over three nights at London's Brixton Academy. On their return visit to the capital in the new decade, at the Marquee, mere hundreds were on hand to greet them.

What’s more, on that Sunday evening on Soho’s eastern border, the Beastie Boys declined to perform a single note of music from their multi-platinum debut album, License To Ill. As if this weren’t quite remarkable enough, no member of the audience seriously expected them to. Certainly, the young man in the front rows who shouted out for the hit single No Sleep Till Brooklyn did so out more in hope than expectation.

“I wanted to play it,” said Mike D, “but he said no.”

The 'he' referenced here was MCA, Adam Yauch, the man today credited with masterminding the group’s transition from the somewhat problematic louts of the License To Ill era to nothing less than the coolest cats on the block for the remainder of their career.

It can’t have been easy. In 1992 the group’s fortunes were hanging by a thread. Three years earlier, the trio’s second album, Paul’s Boutique, died a death at the box office despite being one of the finest, and certainly one of the most innovative, releases of the decade. As their doomed enterprise faded from view, the Beastie Boys’ new record company, Capitol, told them to begin writing fresh material because their latest release was dead - and, anyway, the company wanted to put its efforts into marketing Donny Osmond.

At the end of the '80s, it was simply <<impossible>> to overstate just how low the group’s stock had sunk. The small but vocal army who insisted to anyone who would listen, and many who wouldn’t, that Paul’s Boutique was within touching distance of being a masterpiece were laughed out of the room. It was like going to bat for The Smurfs. It was like saying your favourite band was Showaddywaddy.

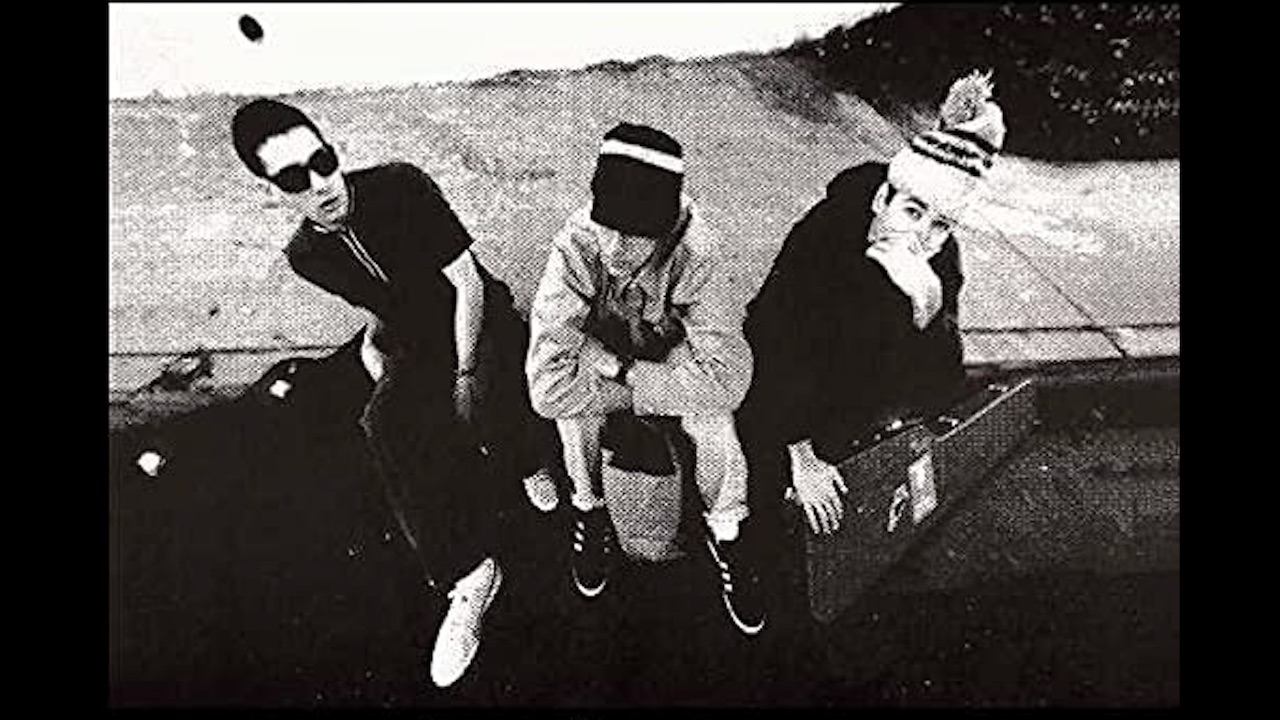

Check Your Head, though, was where the rebuild began to gain traction. Released on April 21, 1992, even the cover art of the 20-track platter suggested differences from the trio’s recent past. Whereas the musical core of Paul’s Boutique had been assembled from a dizzying patchwork of samples – the Ramones, the Commodores, Sweet, Isley Brothers, you name ‘em – the group-photo adorning the front of their third LP featured Adam Yauch, Michael ‘Mike D’ Diamond and Adam ‘Ad Rock’ Horowitz seated around guitar cases.

Back in the day before they were rather briefly very famous indeed, the Beastie Boys were a band who played organic instruments in the hope of sounding like their heroes, the Bad Brains. (That these attempts were entirely hopeless need not detain us here.) Even though the first sound heard on Check Your Head, on set-opener Jimmy James, is indeed a sample – Cheap Trick frontman Robin Zander announcing “This next one is the first song on our new album” is taken from the concert album Cheap Trick At Budokan – a good portion of what follows is music played by drums (Diamond), bass (Yauch) and guitar (Horowitz), not to mention muscular contributions (organ, synthesizer, keyboards, clavinet and Wurlitzer) from unofficial fourth member Money Mark. Other obscure instruments – a cuica, anyone? The mridunga, perhaps? – also feature.

Certainly, here, the Beastie Boys don’t much sound like music-makers sweating under the glaring heat of imminent career extinction. Rather, they seem like people in whose mouths ice wouldn’t melt. Not only are parts of Check Your Head playful, incidental, hypnotic and even psychedelic – Something’s Got To Give, for example, somehow replicates the experience of having a whitey in a flotation tank buried at sea – but at its most off-the-wall the weirdness is almost equal to the group’s impossibly weird Cooky Puss EP, from 1983. Only difference being that back then the trio didn’t have a major label record company on their back griping about a return on a sizeable investment.

Elsewhere, Check Your Head crackles and pops with the kind of hip hop finesse that only the genre’s finest practitioners can attain. Because, make no mistake, when the Beastie Boys decide it’s time to rhyme, the flow and the interplay between them is a wonder to behold. “You’ve got the boomin’ system but it’s sloshing out doo-doo, you think it’s chocolate milk but it’s watered down Yoo-hoo” they rap on the pulsating Professor Booty. On So What’cha Want, likely the album’s most electrifying track, they announce that “you scream and you holler about my Chevy Impala, but the sweat is getting wet around the ring around your collar”. Seriously, beat that.

In what might just have been a surprise to its authors, upon its release Check Your Head debuted on the Billboard 200 album chart at number 10. Then again, perhaps not. Unlike the world into which Paul’s Boutique made its mistimed entrance, by 1992 the weird and eclectic music-makers of the Alternative Nation were, for a time at least, the ruling class of the international scene. In other words, the pitch had been rolled for the public resurrection of the Beastie Boys.

And while it doesn’t seem likely that the group’s paymasters at Capitol Records heard the sound of ringing cash-registers the first time they pressed play on their charges’ second attempt to file a hit record, ring they did. By which point, few were the people who claimed to have ever doubted them.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Barnsley-born author and writer Ian Winwood contributes to The Telegraph, The Times, Alternative Press and Times Radio, and has written for Kerrang!, NME, Mojo, Q and Revolver, among others. His favourite albums are Elvis Costello's King Of America and Motorhead's No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith. His favourite books are Thomas Pynchon's Vineland and Paul Auster's Mr Vertigo. His own latest book, Bodies: Life and Death in Music, is out now on Faber & Faber and is described as "genuinely eye-popping" by The Guardian, "electrifying" by Kerrang! and "an essential read" by Classic Rock. He lives in Camden Town.