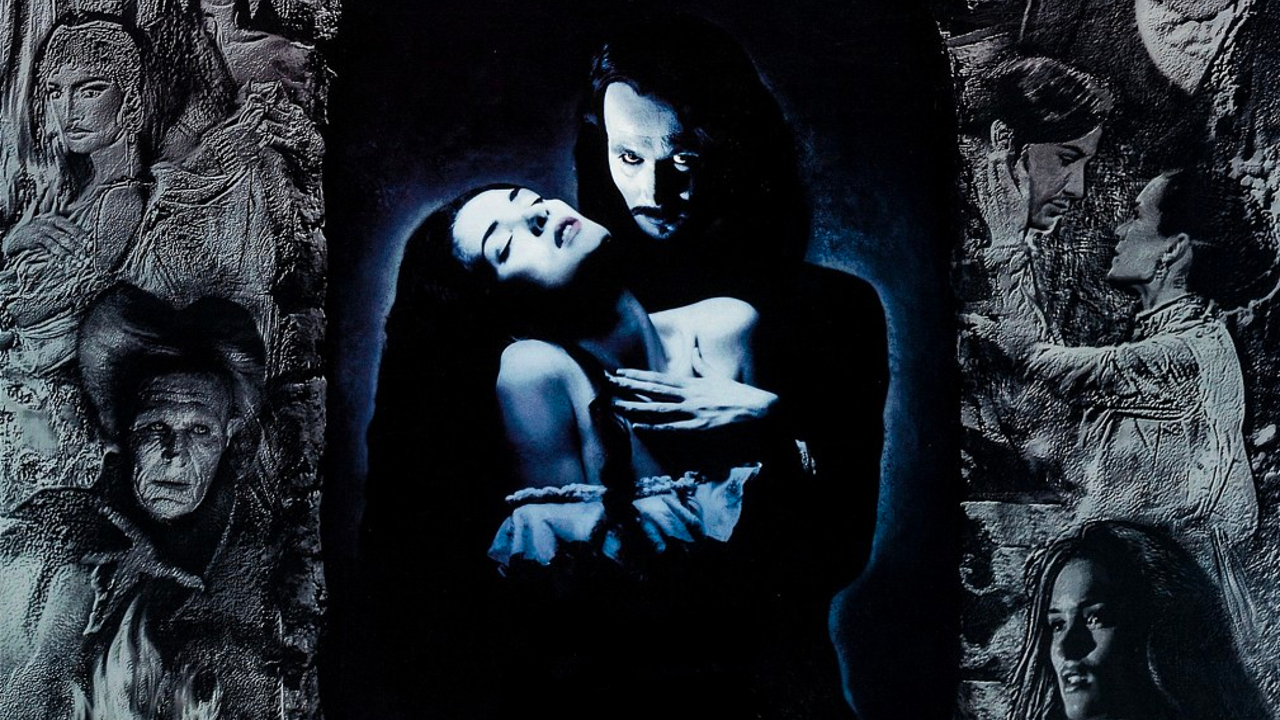

Bram Stoker's Dracula at 30: a love letter to Francis Ford Coppola’s classy, bloody, horny masterpiece

Bram Stoker's Dracula turns 30 this week. Despite being the last thing mainstream horror needed, it smashed expectations and remains a cult classic - and with good reason

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

By 1992, Dracula was seemingly the last thing the mainstream wanted to see in its horror films. Scary movies built around monster antagonists were becoming a punchline, the credibility of Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees assassinated by a torrent of shithouse sequels. Meanwhile, The Silence Of The Lambs had just swept up the five most prestigious Academy Awards. People wanted cinema’s scarers to be real and intelligent, able to blend in before eviscerating you, not some fantastical twat in an outfit.

Yet Francis Ford Coppola created an anomaly. For a fleeting moment between Silence… and Seven, the master behind The Godfather made supernatural evil feel fresh and scary again – and more than a little bit sexy. Its star director, ensemble cast and $40 million budget proved powerful enough to transcend fashions and create a vintage monster movie everybody wanted to see.

Even in 2022, with the film now thirty years old, Bram Stoker’s Dracula remains Coppola’s underrated masterpiece, and has aged more beautifully than every other effects-laden horror of its era. The story remains the closest adaptation of the 1897 novel to date, integrating every key character, every modicum of vampire lore and even the same epistolary narrative structure. On top of that though, it’s also a gothic love story.

In this version, Dracula is a 15th-century warlord that vows vengeance against God and descends to vampirism after the love of his life commits suicide. When, in 1897, solicitor Jonathan Harker attends the monster’s castle to facilitate his move to England, he sees that Harker’s fiancée, Mina, is a reincarnation of his long-dead bride, and plots to tempt her to him while spreading his disease.

As faithful as Dracula is to the book, it’s more a love letter to the birth of cinema than to Stoker’s writing. Bar one effect (a ring of fire that burns blue at the gate to Castle Dracula), everything seen on screen really was in front of the camera. The trickery was intentionally primitive: reliant on miniatures and reverse-footage. Only what the Marx Brothers or Georges Méliès could have had access to would do. Between that, the expansive sets and the regal-looking costumes, every cent of Dracula’s $40 million was thrust onto the screen in a level of dedication likely to never be seen again.

The most veteran members of Coppola’s ensemble – Gary Oldman and Anthony Hopkins, who portray the Count and his nemesis Van Helsing respectively – refuse to get swallowed up by the bombast. Oldman’s performance mimics the dramatic changes in Dracula’s appearance, running the gamut from aged monster to debonair gentleman, while Hopkins communicates the doctor’s experience in his clinical delivery of some distressing dialogue. On the other hand, the younger cast, many of whom were hired for their name factor, butt heads with the grandeur of their surroundings. Keanu Reeves’ Jonathan Harker especially seems wooden inside the granite walls of Dracula’s castle, stuck in a stiff English accent that, due to the intensity of his early-’90s schedule, he did not have time to refine.

In hindsight, it’s amazing that Dracula remains a classic of blockbuster horror when the film was pushed into existence not out of passion for the novel, but a need to stay financially afloat. By 1990, Coppola and his production company, American Zoetrope, had already gone bankrupt twice, owing to such flops as One From The Heart, and were looking down the barrel of a third trip to the adjudicator’s. To compile some cash, the auteur made The Godfather Part III, which grossed $130 million but was lambasted as the nadir of the series, then decided to quickly follow up with Dracula after Winona Ryder (who’d just dropped out of playing Mary Corleone) presented him with James V. Hart’s screenplay.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

There was an overarching eroticism to the script, which cast Mina as a repressed young woman in Victorian London, with Dracula representing a passionate and exotic escape. Coppola played into the sexual themes. He emphasised the intimacy of the vampiric neck-biting and of Mina drinking Dracula’s blood (which is in fact in the book, just rarely adapted). The hypnosis and attack of Dracula’s first English victim, Lucy, is depicted as a seduction that climaxes with her wandering outside in semi-transparent nightwear for an out-and-out sex scene.

To help achieve the film’s lustful tone, Coppola made production as randy as possible. During a moment where Lucy writhes alone in bed mid-transformation, the director had Oldman speak seductively to actress Sadie Frost from offscreen. She later called what Oldman said to her “very unrepeatable”. Coppola even went so far as to hire an acting coach especially for guiding Ryder and Frost through their sexualised sequences, as the prospect of doing it himself made him uncomfortable.

Ryder also allegedly felt the brunt of Coppola’s brutal approach to direction. During the scene where Mina and Dracula first meet, Oldman flashed a courgette in front of his crotch to get what was deemed an appropriate response from the actress. Furthermore, Coppola instructed Oldman to say intimidating and improvise lines to Ryder, hoping to enhance the horror in her performance. She quickly fell out with Oldman, finding his intensity overwhelming, although the two later reconciled. Ryder also wrote in her diary during production: “Angst. Angst. Angst. Angst. Thank God for Keanu Reeves. Thank God I’m going to see Keanu.”

The practicality of Dracula’s special effects was of paramount importance to Coppola, as the late 1890s coincided with the birth of cinema. When the film’s visual team told him that the shots he wanted to do were impossible without green screens and CGI, he sacked every one of them, then hired his son, Roman, in their place. Despite being a clear nepotism pick, the junior Coppola fulfilled his role spectacularly. The father and son’s commitment was such that, for the opening of the scene where Dracula takes Mina to the cinema, they used a contemporary, hand-wound Pathé camera from Francis’ collection.

After Coppola and American Zoetrope filed for bankruptcy a third time in July 1992, Dracula needed to make money upon its release that November. Initial projections were grim, as those who saw the film in advance deemed it too much of an auteur project – too weird, erotic and mature – to be a mainstream hit. However, thanks to the number of stars attached to it, Dracula reached the top of the American box office before ultimately grossing $215 million, recouping its production budget more than five times over.

In the longer term, Dracula ignited a brief resurrection of the vampire myth. Two years after its release, Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt starred in Interview With The Vampire, which earned box office success and global acclaim, before Quentin Tarantino wrote and starred in 1996’s From Dusk Till Dawn. Then came Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Blade. Meanwhile, Coppola capitalised on his newest hit by producing another horror adaptation, the Kenneth Branagh-directed and Frank Darabont-written Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. However, the end product crumbled under the weight of its own weirdness and didn’t become the hit the filmmakers envisioned.

Now that he’s retired into low-budget and just plain weird personal projects, ...Dracula remains Coppola’s last masterpiece. It’s also, in an era of increasingly economical CGI, likely going to remain the last of its kind: a swan song to the onscreen magic tricks filmmakers employed before Hollywood became...well... Hollywood. Clashing with those vintage values is a sexuality that affronts conservatism, making Dracula a timelessly compelling and controversial work of art.

Louder’s resident Gojira obsessive was still at uni when he joined the team in 2017. Since then, Matt’s become a regular in Metal Hammer and Prog, at his happiest when interviewing the most forward-thinking artists heavy music can muster. He’s got bylines in The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, NME and many others, too. When he’s not writing, you’ll probably find him skydiving, scuba diving or coasteering.