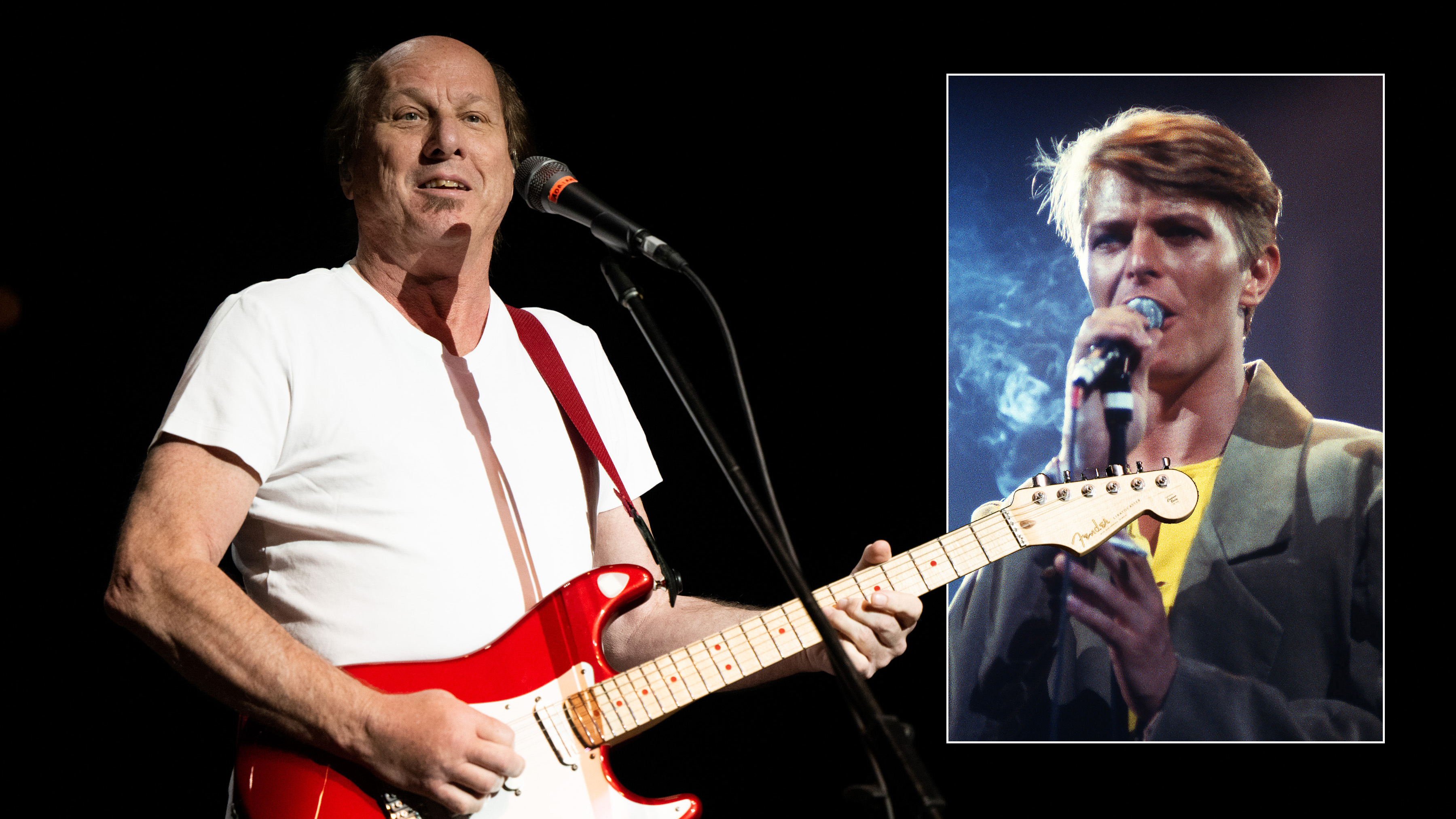

“David Bowie’s Lodger was supposed to be called Planned Accidents… I was the accident!” Adrian Belew on being poached from Frank Zappa’s band

King Crimson and Talking Heads veteran recalls having to record for Bowie without hearing the songs first

Despite his work being familiar to millions thanks to his extraordinary contributions to classic singles including David Bowie’s Boys Keep Swinging, Talking Heads’ existential classic Once In A Lifetime and the utterly joyous Genius Of Love by Tom Tom Club among countless and diverse others that also include Nine Inch Nails, Paul Simon and Laurie Anderson, Adrian Belew’s name is not one that prompts the response it deserves from Joe Public. But to those in-the-know, he’s recognised and revered as one of the most inventive, forward-thinking and outright progressive guitarists to have broadened the scope of the instrument.

A prodigiously talented autodidact groomed under the wing of Frank Zappa, he’s probably best known round these parts as the singer and guitarist of King Crimson. Introduced to founder and guitarist Robert Fripp by erstwhile and mutual employer David Bowie, they were joined by bassist Tony Levin and drummer Bill Bruford, and the new line-up released three celebrated and highly influential albums in the shape of Discipline (1981), Beat (1982) and Three Of A Perfect Pair (1984) before taking a break for over 10 years and then returning with their famed “double trio” line-up.

In between, Belew has continued contributing his unique guitar playing to a variety of artists as well as concentrating on his band, The Bears, and his own steady stream of solo albums. Indeed, with his 25th solo album, Elevator, the fabulously polite Adrian Belew is the very definition of a Southern gentlemen as he looked back with Prog at his career in August 2022.

You started as a drummer in your teens. How, why and when did the guitar become the instrument for you?

Aged 16, I got sick with mononucleosis [glandular fever] and had to stay home for two months. I couldn’t play drums and had to stay in bed. I borrowed a guitar from one of my then-bandmates and I taught myself to play. And when I went back after two months I had written five songs. I played them for them and they said, “What the heck are those chords?” Because I didn’t know how to play, I worked it out by putting my finger on the note I wanted, then thought, right, where’s the harmony? So I ended up with all these crazy chords!

Have you ever had any formal guitar lessons?

No. When I was in the marching school band, they taught me how to play marching cadences on the drums, but I’ve had no proper guitar training at all and have taught myself all the instruments that I play. I love doing all that, and it’s one of the reasons I play all of the instruments on my solo records.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Where did your fascination for sound manipulation come from?

As a child, I used to watch these cartoons – Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck and all of those – and I’d try to mimic the sound of the different characters. I always seemed to have a good ear for figuring out sounds. Sound always fascinated me, like I could hear the rhythm of life when I was young.

I saw a cellist on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, and he was a comedian. At one point he was joking around and he made his cello sound like seagulls with the bow and I thought: Oh my God! That’s fantastic! I wonder if I can do that with the guitar?

You came to Frank Zappa’s attention when you played with covers band Sweetheart. What do you think he saw in you?

My guitar playing had started to be my own. I was doing car horns in solos, but he never really said much to me about my guitar playing and later on he was quoted as saying that I reinvented the electric guitar. He needed someone for the music he was writing that could do a lot of vocal styles. Not a lot of people know this about Frank, but he was not coordinated – in his opinion – to play guitar and sing at the same time; it was either one or the other. So when he was playing guitar, I would sing and when he was singing, I was playing guitar.

And that was my role, but also my role was to be a little theatrical. He would say to me, “Adrian, would you wear a dress onstage?” And I’d say, “Sure! Why not? I’m in Frank Zappa’s band; that’s what they’re known for!” I loved it and it was a great education. I loved Frank so much and he was really generous to me.

That three months that we rehearsed, it was five days a week, 10 hours a day and I learned five hours’ worth of Zappa material. At weekends, I’d go home with him and he’d teach me what’s coming up next. Being self-taught, I was the only bandmember not reading from sheet music.

You fell short in your first audition for him and asked for another chance. What happened?

I came in during the early part of the day, and it was in his basement, which eventually would become a fantastic studio over the years. It was a construction project that never ended! Every time I went up to Frank’s house it was like, “Oh, there’s another room, then, added on!” [He’d say:] “Yeah, we moved the pool!” Anyway, at that time, they were moving gear around and Frank was sitting there at a studio console. I’d start playing and singing and then someone would walk by with a drum kit! I couldn’t concentrate.

Eventually, all the activity had quieted down and there’s just me and Frank. And I said, “Frank, I’m really sorry. I know I didn’t do well. I just had a different idea of how it would be done,” and he said, “Well, what do you mean?” I said, “I thought it would just be you and me somewhere quiet, and I can show you that I can do this.” I did the audition again, and about a third of the way through, he was singing along with me and he reached his hand out and said, “Okay, you’ve got the gig.” It’s a good thing that I had the nerve to do that because I was so disappointed in myself and I actually felt like I’d let this guy down.

What lessons did you learn from Frank Zappa?

He taught me how to play in odd time signatures. He said, “I don’t hardly play in 4/4, so you’re going to have to learn how to play in odd time signatures.” The way he explained odd time signatures to me – coming from a background as a drummer – made total sense to me; it was all about accents. That was a really important thing when I got into King Crimson. I don’t think I would ever been able to write the stuff necessary had I not learned it at that point.

Moreover, what I think I got from Frank was a truly, almost crash course in how to be a professional, world-class touring musician and recording artist: having your own business, putting out your own records, having a band; every little aspect of it. He took me through the mastering process once. We did a movie together and I saw how all of that stuff works. Every single day it was just one lesson after another but done in a fun way; he was hilarious! I always say I graduated from the School of Zappa.

Did David Bowie really make his musical move on you in front of Zappa?

Yes. There was a portion of the show for about 10 minutes where I left the stage while Frank took a guitar solo with just the bass player and drummer. As I left the stage, I saw David standing there by the mixing board. I thought, I’ve gotta say something! So I shook his hand and said, “I just want to say thank you for all the fabulous music you’ve made.” And he said, “Great! How would you like to be in my band?” I turned around and said, “Well, I’m kinda playing with that guy out there on the stage!” He laughed and said, “Yes, I know, but when your tour ends, mine starts two weeks later. Maybe we should talk about this? I’ll come to your hotel and we’ll go out to dinner after the show.” I could not believe that!

David was a personal hero because I always thought that David did something I wanted to do in music, which is combine the avant-garde art side of music with the pop side. I’ve been trying to do that ever since.

You reportedly recorded your parts for Bowie’s Lodger without hearing the songs first and were given just three passes to make a contribution. Is that true?

Three if I was lucky! I think sometimes by the second pass I knew where the chorus was and they said, “Okay, that’s it! No more! He’s starting to get wise to it.” They wouldn’t even tell me the key of the song. The studio was above the control room. I couldn’t see them but they had a one-way television camera that could see me, so they said, “Put your headphones on, you’ll hear a click and start playing.” I was like, “Play what?” “Whatever you think of.” It was a method that they came up for getting your accidental responses. At one point Lodger was supposed to be called Planned Accidents, so I was the accident! Then they would make a composite of their favourite things into one guitar track.

What did you make of Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies as a creative tool?

I love all that stuff! I think it’s thought-provoking, and even if it does nothing, it gives you a mindset to try to move the room around a little bit. Sometimes it worked, I guess. I mean, he didn’t use it that often there and I don’t know if he used it when I was making Remain In Light with Talking Heads either, but they did pull the cards out once or twice. Most of the time we kind of giggled at him!

Was it Eno who introduced you to Talking Heads?

No. I met Talking Heads when they were touring around the area I lived in. I went to three of their shows and the third show I went to, they asked me, “Would you come play our encore with us?” They had seen me play with Bowie at Madison Square Garden. They were in the second row and clearly I saw them, and so I know they were impressed in some ways and so they said, “Would you come out and play our encore, Psycho Killer?” And I said, “I know the song, but I’ve never played it before” and they said, “Don’t worry – just wait until the end and just freak out like you do!” No one tells me what to do; they just want that crazy stuff!

I was then playing a show with my own band in New York trying to get a record label to listen to my music. We did a couple of shows and David Byrne, Brian Eno and Jerry Harrison were there. They cornered me in the stairwell after the show and said, “Hey, how long you in town?” I said, “We’re driving back tomorrow to Illinois” and they said, “Could you just stay for one day and play on this record we’re making?” And so the next day I went into Sigma Sound in New York City and in one day made Remain In Light.

How did your relationship with King Crimson come about?

My solo band was the opening act for Robert Fripp and his League Of Gentlemen around the Midwest. He got a kick out of my show and I think he realised, “Maybe this is the character I’m looking for?” I think he knew he needed a partner guitar player and possibly a partner songwriter.

The first time I met him was at the Bottom Line in NYC and he wrote his number on my arm with a Sharpie! And I’m like, "Okay, I guess I’ll call this number then!" We went and had coffee together and during that conversation I think I surprised him by letting him know how much I knew about all of the early King Crimson catalogue. I was a huge a fan of all that music and it was second only to The Beatles.

Talking Heads went to London on our tour and for the first night there we went to a Russian restaurant; we got absolutely plastered on flaming vodkas. I wasn’t a drinker so it was terrible for me when, at 8am, the phone rings and it’s Robert who says, “I know that you’re not one to be raving so I thought I could call you this morning.” I said in a croaky voice, “Could you please call me back in about three hours?” I was that miserable! He did call back and said, “Me and Bill Bruford would like to start a band with you.” I was stunned because Bill Bruford was my favourite drummer in the world!

What freedoms were afforded you as a member of King Crimson?

The job was multitasking because I needed to write whatever material was going to be sung. So Robert and I would develop some ideas together and if I said, “Well, I think I could make a song of this,” he’d say, “Okay, then it’s up to you. Now you write the words; they have to be your words and your melody because you’re the singer.”

The other role was being the frontman and that didn’t bother me. But the hard part for me was adapting to Robert’s precise style of playing. It wasn’t my style at all and we practised that for four to five hours every day to get me up to speed with being able to do that. Then the next problem was, okay, now you’re playing together based on Robert’s precision, how do you write a song to that? It puzzled me for six weeks and finally I locked in and said, “Okay, I think I got this now” and that became the makings of the Discipline record.

I will say this: Robert always gave me total encouragement: “Whatever you need; if you need the keys to change here; whatever you need, Ade.” He was really supportive of me all the way. There were kind of guidelines and rules about what worked in the band and what you didn’t do. I always said it’s kind of like having a box of 24 crayons and you just take out six now, and these are the ones you’re allowed to use. The rest of you can’t. I mean, it was hard! I spent more time on the words than anything and I wish I got more credit for being the lyricist. Nobody ever says anything about the lyrics, but the lyrics were the hardest part for me!

What are the differences between Adrian Belew: the solo artist and Adrian Belew: the collaborator?

As a collaborator, I have to be very careful with what I’m offering up, especially as a lyricist. I’m always very keen to make sure I wouldn’t talk about things or say things in a manner that might embarrass someone else. I can often tell what is really for me – this is my personal view or this is really for Crimson.

With my personal stuff, anything goes; I like to do funny things, even. Sometimes, I don’t know that that works well within the stricture of a serious band like King Crimson because there is a different level to it.

How is it that your unique and recognisable sound fits so seamlessly into a variety of genres?

I think it’s my musical ability and knowledge that I’ve collected through years of experience. If you say you have something or an idea of what you could affect on this particular piece of music or song, I will probably have several. And it doesn’t really matter whether it’s a heavy thing like Nine Inch Nails or one of Paul Simon’s songs from Graceland, I still will probably have some ideas. So that’s what I think people come to me for; they rarely tell me what to do – they’ve asked me, “What would you like to play?” Well, it’s easy! I can think of something like falling off a log. And I’d rather think of something than falling off a log!

Elevator is your 25th solo album. What motivates you to keep making music?

I really can’t stop myself. In fact, it just pours out of me more than ever. I’ve gotten better and better at writing things quickly and lyrics don’t struggle me up so much anymore at all. But I did get a rest and it was called Covid. There we were stuck at home. Man, for a while I was going nuts, so I just started really diving in and creating.

When I realised it’s a milestone, I also thought, I’m going to damn well make the best record I can. It was really a great thing to do and I love it and I can’t wait to play it for everyone.

Given the depth and breadth of your work, where should the novice begin?

I would honestly start with Elevator. I would go there and work my way backwards. If you loved Elevator, you’ll wanna hear Pop-Sided, the one before. And if you love that, you might go back to Mr Music Head and eventually reach all the way back to Lone Rhino. Of course you should go listen to Discipline, you should listen to Remain In Light, you should listen to something from Bowie and all that stuff. But if you wanna know me, then start with my solo records. Good luck – and I’ll see you in 20 years!

This article originally appeared in Prog 132.

Julian Marszalek is the former Reviews Editor of The Blues Magazine. He has written about music for Music365, Yahoo! Music, The Quietus, The Guardian, NME and Shindig! among many others. As the Deputy Online News Editor at Xfm he revealed exclusively that Nick Cave’s second novel was on the way. During his two-decade career, he’s interviewed the likes of Keith Richards, Jimmy Page and Ozzy Osbourne, and has been ranted at by John Lydon. He’s also in the select group of music journalists to have actually got on with Lou Reed. Marszalek taught music journalism at Middlesex University and co-ran the genre-fluid Stow Festival in Walthamstow for six years.