"We want to appeal to everybody and get rich quick. We want to be millionaires": How AC/DC's plan to conquer the world began in the back of a squalid bus

We travel back to 1976 to spend time with AC/DC as they clamber the first few rungs on stardom’s greasy ladder

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In 1976, much-missed UK music weekly Sounds sponsored AC/DC's Lock Up Your Daughters tour, a jaunt that took in such salubrious venues as the Civic Hall in Bedworth and Gravesend's Woodville Halls Theatre. Sounds dispatched young writer Geoff Barton to cover the action as the band travelled to the Porterhouse in Retford, an encounter he revisited for Classic Rock in 2004.

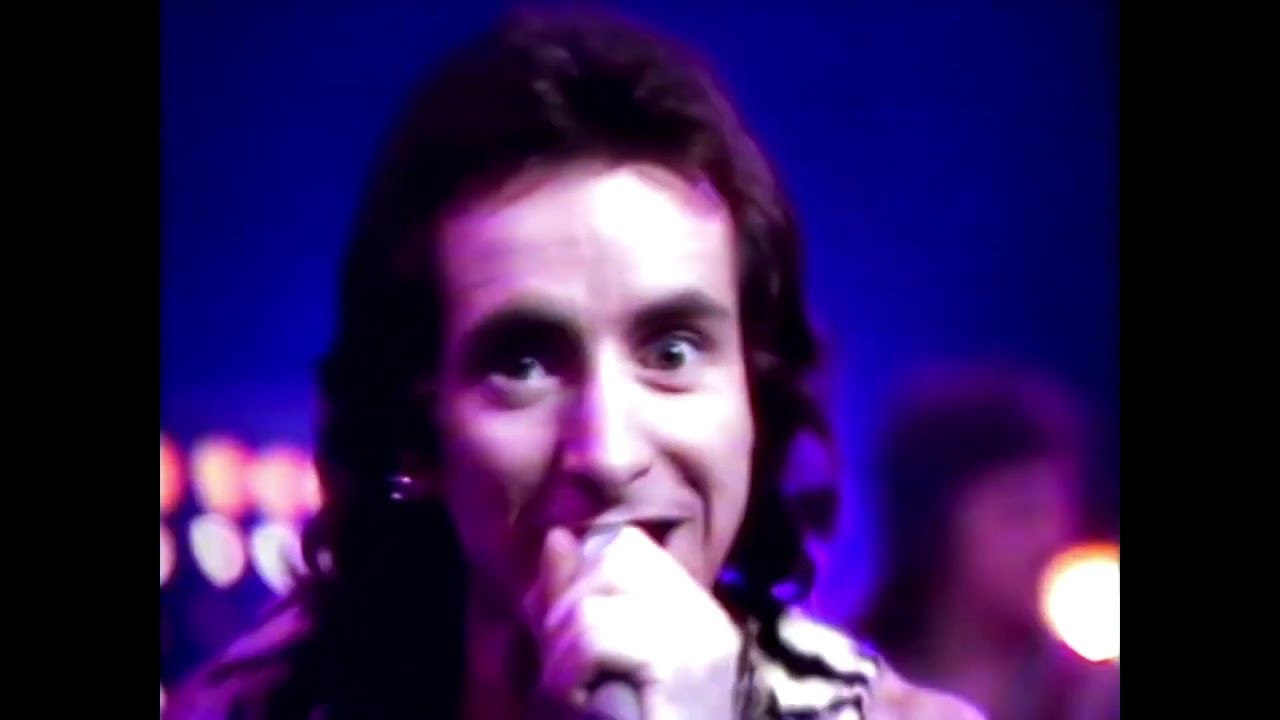

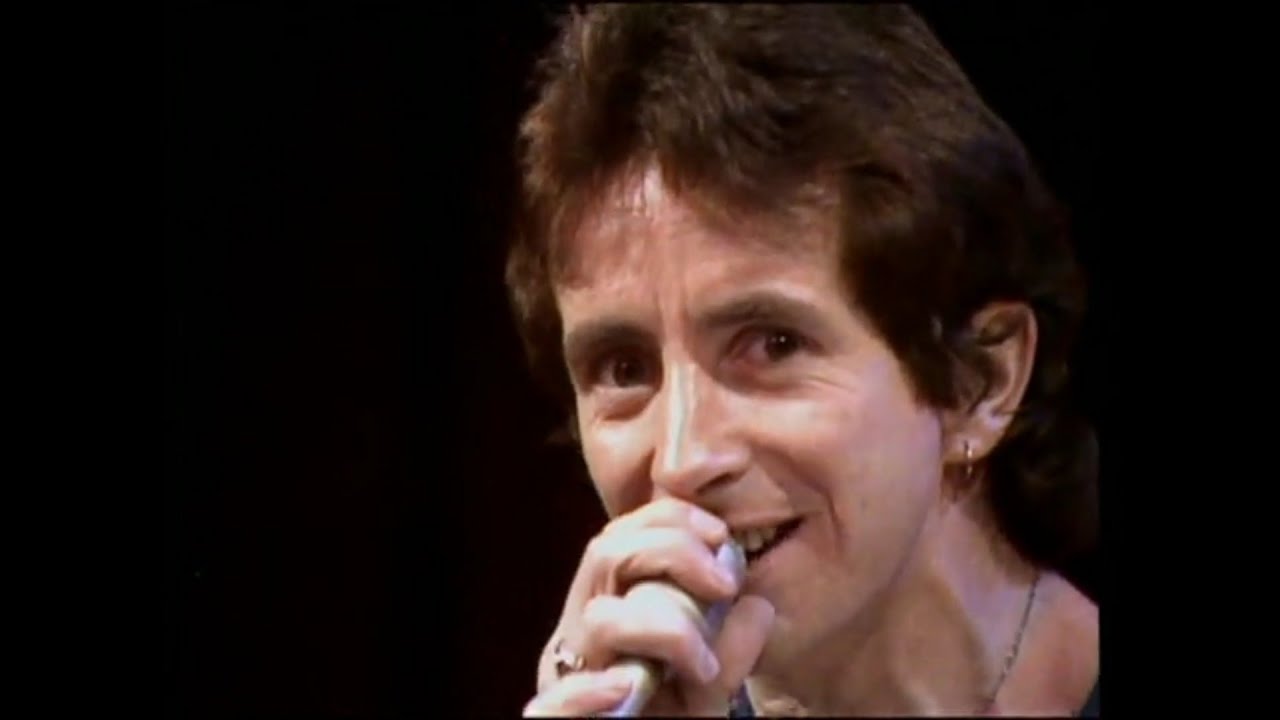

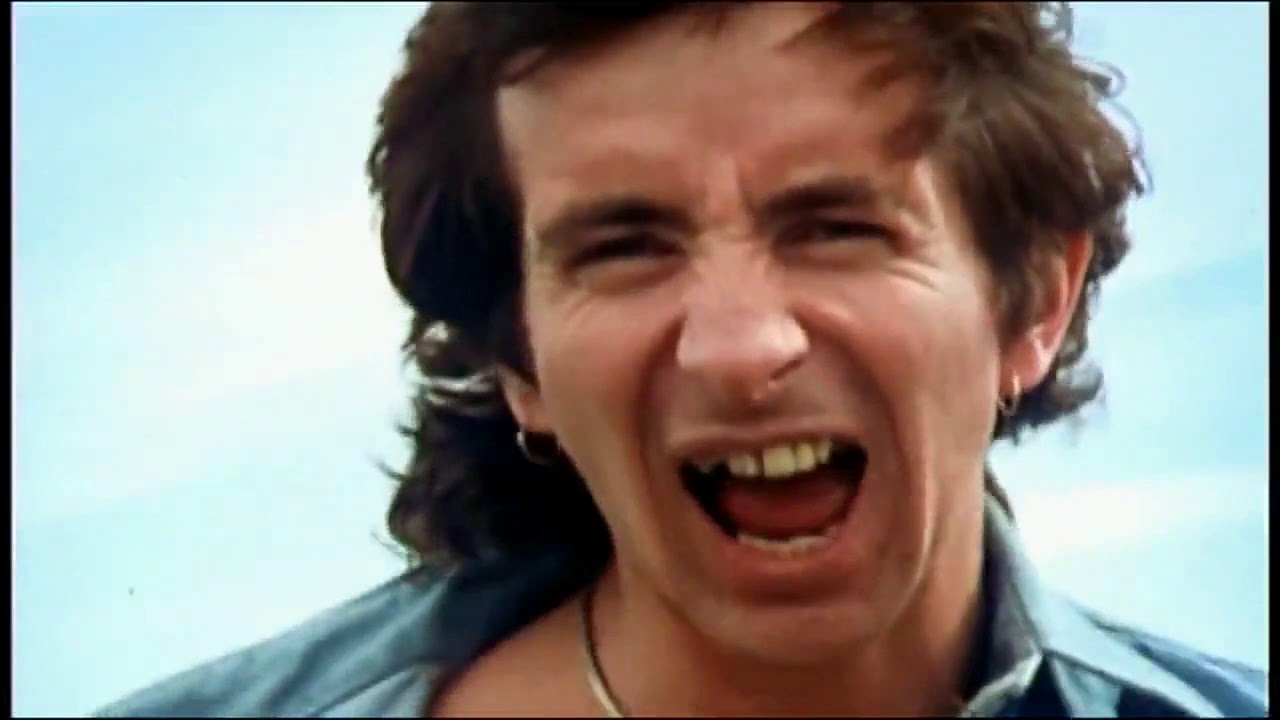

We are knee-deep in adult magazines. The entire floor of the tour bus is awash with them. AC/DC singer Bon Scott climbs on board and spreads-eagles on the backseat. He snaffles up a title at random, flicks through its pages and flashes his soon-to-be-trademark lascivious grin. As the remaining AC/DC members follow Bon inside, a handful of copies of Club International fall out on to the pavement. No matter. There’s plenty more where they came from.

It’s a rather decrepit bus, truth be told, with dirty beige bodywork, rusty holes around the wheel arches and a creaking interior apparently lifted from an old London Routemaster. Nevertheless, as the vehicle’s engine wheezes into life, AC/DC’s mood is buoyant. We might not be on the Highway To Hell – we’re actually on the more prosaic Road To Retford – but the band’s adventures are just beginning.

It’s May 1976, y’see, and they’ve got a long, hot summer (hang on, better make that career) ahead of them. Guitarist Angus Young sidles into position just across the aisle from me. Eschewing the hard-core publications tumbling about his feet, he pulls a crumpled copy of his own from his back pocket. Strangely, it isn’t Penthouse, Playboy or Plumpers And Big Women (a particular favourite of Bon’s, as he will explain in future song Whole Lotta Rosie). No, it’s a copy of The Beano. Well, Angus is only 16 years old, after all…

Fashback to an hour or so earlier. Two of Angus Young’s schoolboy outfits have just arrived back from the dry cleaner’s – one red, one black, each is folded neatly inside rustling, protective clear plastic. Coral, AC/DC’s publicist, holds up the tiny velveteen twin-sets and casts a critical eye over them. Her verdict: the blazers and shorts are spotless.

“Thank God,” Coral sighs. “I was afraid that the shop would refuse to handle them, they were absolutely filthy. Angus sweats a lot, you see, and we have to clean them regularly. It’s unheard of for him to wear the same suit two nights running. And, on top of that, when Angus gets carried away on stage – you know how it is – his nose begins to run. Ugh! There are always some horrible streaks of snot down the fronts of his jackets,” she grimaces.

We’re waiting in a home-cum-office being rented by AC/DC’s manager Michael Browning near Piccadilly in London, preparing to catch a taxi out south-west to the band’s temporary home in leafy Barnes. From there we’re scheduled to travel with them in their van to tonight’s gig at a club called the Retford Porterhouse.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The Antipodean band have been in Britain for a month or so now, the first group from Australia ever to make a calculated stab at the big time in this country. And so far they seem to be doing pretty well. AC/DC’s were originally scheduled to appear as support to Back Street Crawler on an extensive UK tour, but plans went awry when the headliners’ guitarist, ex-Free man Paul Kossoff, died suddenly and the band’s date schedule, for obvious reasons, was cut drastically.

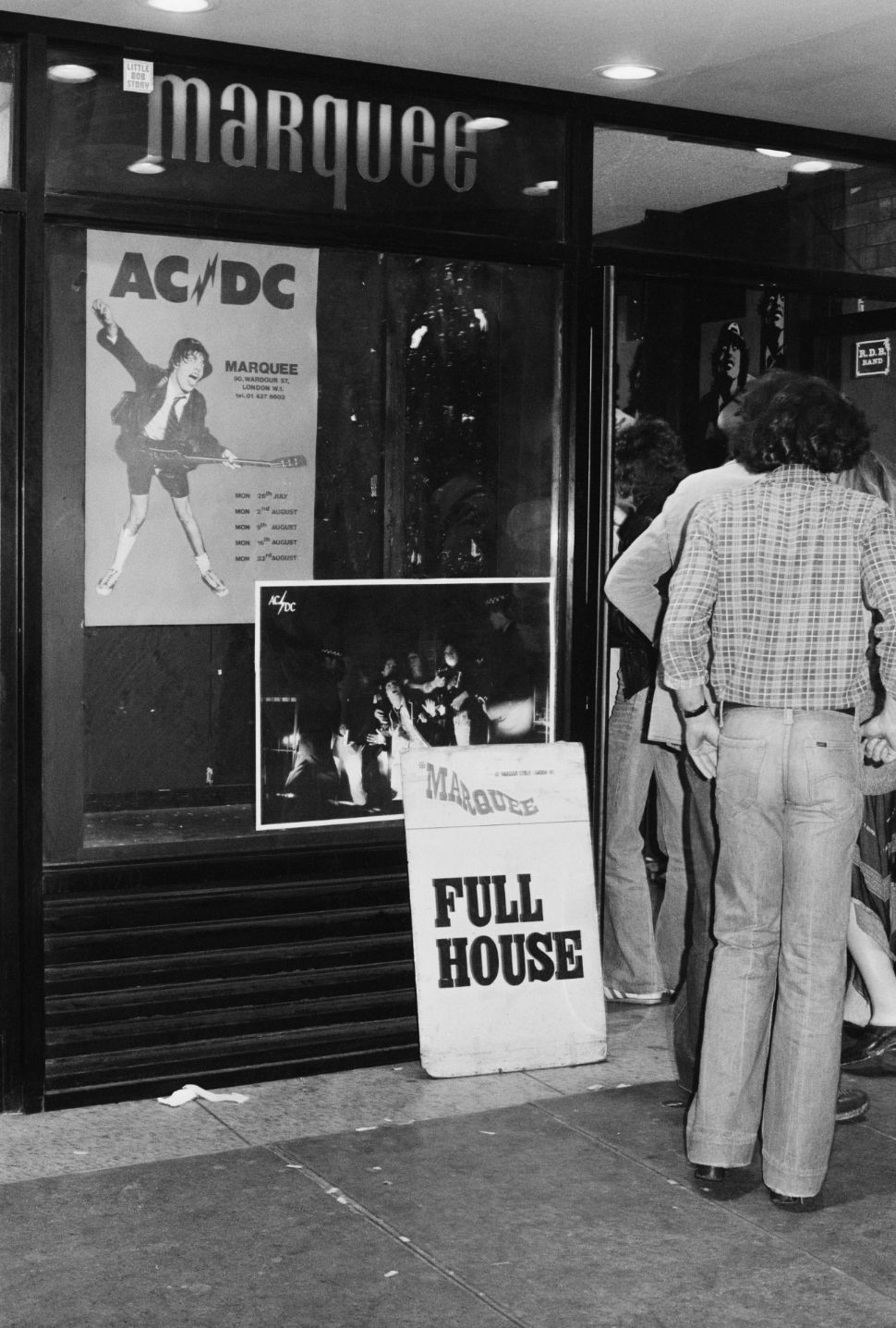

For the moment, AC/DC have contented themselves with picking up odd dates when and where they can, mostly around the London Marquee/Nashville/Red Cow club-pub circuit, occasionally venturing further afield – to showplaces such as Retford, for example. No doubt their ambitions will be set back onto the right track when a headlining tour begins on June 11 (1976) at Glasgow City Hall. For the moment, however, it’s over to Barnes in a cab.

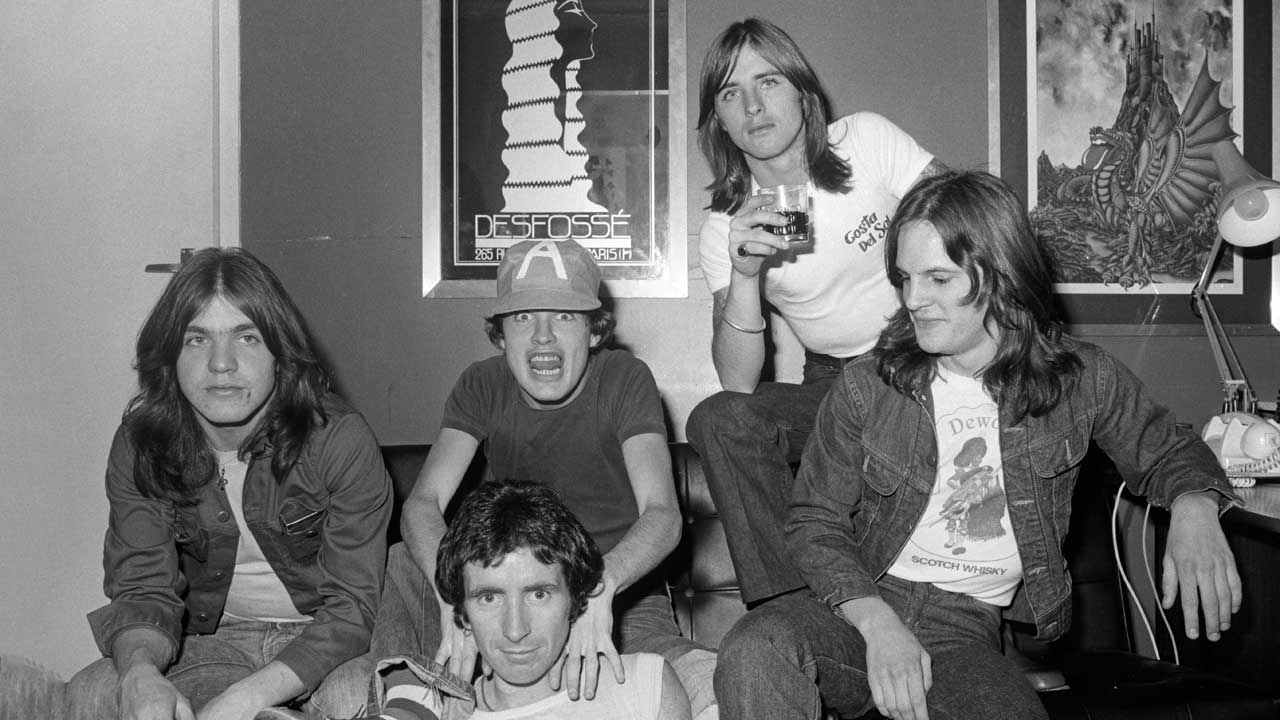

The AC/DC residence is a large, congenial detached house. It’s cosy, if cluttered – cigarette butts and half-finished drinks are strewn liberally about its interior. The first thing that strikes you about the band is their smallness – apart from singer Bon Scott, they’re all about five feet, four inches. The second is their fresh-faced, bright-eyed appearance. On closer inspection, however, you find that their skin looks a good deal more leathery than it should, and their eyes are glazed more than shiny. On-the-road wear and tear, without a doubt.

Angus Young, slumped on a sofa, is the runt of the band. Purported to be aged 16 (he was actually born in 1955), it has to be said that he looks even younger. Wearing a tiny jumper, an incredibly narrow-waisted pair of jeans and a pair of dainty tennis shoes, he could have been kitted out at a Mothercare store.

The others I take to be typical Australian scruffs, the sort our own token Aussie Jonh Ingham – the highbrow Sounds punk writer who would later go on to manage Billy Idol’s Generation X – would no doubt rather disown than associate with. They are Malcolm Young (Angus’s brother), Phil Rudd, Mark Evans and Bon Scott. The oldest and most well-worn of the five, Scott got himself into a fight as soon as the band arrived in Britain, and consequently the first AC/DC publicity shots showed him wearing shades to cover up the bruises.

Scott leers at me in a half-friendly, half-threatening way through his unkempt mop of curly dark hair. He points proudly at his battle scars: a pair of still-angry blue-black shiners. “The other guy came worse off,” he snorts.

Around late afternoon, we pile into the van to head for Retford, which, we discover, appears to be somewhere near Nottingham. As we set off, an eye-boggling collection of adult magazines is immediately brought out from under the seats for all and sundry to ogle at. All, that is, except Angus – he reads a comic.

After a long and rather tedious drive, we arrive at the venue at about 10pm. Up flights of stairs and through a couple of swing doors, and the Retford Porterhouse is revealed in all its dubious splendour. The culinary experts among you will know that porterhouse is another name for sirloin steak – but tonight’s audience is not well done, or medium, or even medium-rare. It’s just rare.

The band members’ mouths, formerly beaming, upturned and happy, all drop to resemble inverted boomerangs. In the whole of the club, which extends in a sort of squashed T-shape over some distance, there are probably about 30 people. But it’s early yet, apparently; for the place to be this empty at such a time of night is not at all unusual, the club manager insists. Not that his assurance boosts the band’s now-flagging morale any.

![AC/DC - It's A Long Way To The Top [Official Music Video], Full HD (Remaster, Resync and Upscale) - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/g-qkY2yj4_A/maxresdefault.jpg)

AC/DC still feel rather uncomfortable in British gig situations. After having plodded around the Aussie club circuit for a number of years, it must seem very strange to have to adjust to a rather different style of touring life.

But thankfully the atmosphere in the cupboard-sized dressing room is not at all formal or restrained. “It doesn’t matter if there’s one person or a thousand out there, we’ll still put on a good show,” comes the trouper’s quote from the band’s frontman, Bon Scott.

I decide it’s about time to set up my tape recorder and do an interview, hoping that the microphone will pick up AC/DC’s voices and not the “Hi there, beautiful people, here’s a great, great, sound from…” spiel of the club DJ, and the cheesy 70s sounds from the likes of Suzi Quatro and Mud that are thudding insistently and continuously through the dressing room walls.

As I expected, a likeable bunch though they are, AC/DC aren’t the most articulate of fellows – a ‘fuck’-in-every-sentence band, in fact – but are quite lovable in a coarse-but-kind-hearted way. The spokesmen turn out to be Angus and Bon. We begin by talking about the band’s early days, and it transpires that only two founder members remain – the brothers Young.

“Yeah, me and him,” Angus says, motioning toward his rhythm-guitar playing brother, who is sitting in a corner munching a greasy chicken-in-a-basket meal. “Malcolm got the band together at the end of ’73 or thereabouts. We were living in Sydney at the time, and we started to play the local dance club circuit.”

By 1973 the Youngs had been resident in Australia for around 10 years. A Scottish family, they emigrated in the early 60s to begin a new life in the southern hemisphere.

“Me dad couldn’t get work,” Angus drawls in his distinctive Aussie twang – no trace of a Scottish accent to be heard. “He found it was impossible to support a family of our size [two parents, seven sons, one daughter] so he decided to try his luck down under. This was when people were being encouraged to leave Britain. You got your fare to Australia for just ten pounds.”

Angus, the youngest of the family, “the bottom rung” as the smirking Scott calls it, is a strange little tyke. Possessor of boundless energy, extraordinary curling lips, a speaking voice that slurs/slurps at the end of every sentence, he’s mature in many ways, although he doesn’t drink at all.

“If I drank I’d be off,” he says. “The other members of the band have to drink to come up to my level.”

“He doesn’t want to make things too hard for us,” Scott laughs, handing the diminutive guitarist a can of non-intoxicating Coca-Cola.

But anyway, in their earliest days, in Australia, AC/DC were really a teen-scream band, and placed more emphasis on the bisexual connotations than the electrical aspect of their name (apparently they got their moniker from the label on the back of a vacuum cleaner). AC/DC stands for alternating current/direct current in electrical parlance, but of course the term is also be used to describe someone who ‘swings both ways’.

“But we were still playing rock’n’roll,” Angus asserts, “it was just that we didn’t really know what sort of market we were aiming for.”

“The only member of the band who actually played up to the sexual aspects of the name was the old singer [Dave Evans],” adds Bon, who as well as being a Scott turns out to also be a Scot – his family emigrated to Australia in 1952 when he was age six. “He [Evans] used to come on like Gary Glitter, but nowhere near as good. A pretty boy. But the rest of the band was much the same as it is now.

“In fact when I first saw AC/DC, before I joined them, my first reaction was to label them a sex-oriented outfit. But thinking about it now, it was the electrical aspect that came on stronger than anything else.”

Bon’s real first name is Ronald, but when he moved to Australia the neighbourhood kids made fun of him by calling him Bonnie Scotland. The name was later shortened (after a few fistt fights along the way, no doubt) to Bon Scott.

A turning point came when AC/DC left Sydney to try their luck in Melbourne. By this time Bon Scott (originally the car driver for the group) had inveigled his way into the position of band vocalist. Despite local prejudice that anyone who tried to make a living out of music was a shirking layabout and probably a ‘pooftah’ to boot, Scott had previously tried his luck as a drummer-cum-singer in Oz bands The Spektors, The Valentines and Fraternity, before being laid low after a serious motorcycle accident. After recovering, he odd-jobbed for a while and then began to roadie for AC/DC.

When Dave Evans failed to turn up for a gig, Scott – who also had a very brief spell as AC/DC’s drummer – suggested he should stand in as frontman. After that no one dared ask Bon to step down. The band acquired the services of drummer Phil Rudd and bassist Mark Evans in about mid-’75, thus securing their present (’76) line-up.

“In Australia, Melbourne is really the home of rock’n’roll bands like ourselves,” Angus says. “If you want to make it really big as a band you have to move to Melbourne. The city is the hub, the heart, where the biggest demand is. If you’re big there, you’re big all over.”

Working in Melbourne through late ’74 and early ’75, the band dropped the sexual connotations completely to concentrate purely on high-voltage rock’n’roll.

So are AC/DC the biggest band in Australia at this mid-70s moment?

“I’d say we are,” Angus replies, immodestly. “There are three or four top bands back home, Skyhooks and Hush among them, but each tends to cater for a certain audience. We’re the only band that’s able to cover the whole spectrum.”

“This is what we wanted from the start,” Scott asserts. “We want to appeal to everybody and get rich quick. We want to be millionaires. I’ve got this plan to buy Tasmania, you see…”

I mention Angus’s school uniform. Apparently he’s had it from the band’s inception, and can never see a time when he’ll go on stage wearing anything else.

“It was originally a one-off thing,” he says. “I was playing in this band before AC/DC, and the drummer talked me into doing something outrageous, so I dressed up like a school kid; I became a nine-year-old guitar virtuoso who would play one gig, knock everybody out, and then disappear into obscurity. I’d have become a legend.”

“But for some reason he kept on doing it,” Scott continues. “Everyone was imitating Gary Glitter at the time, so Angus decided to do something a little more original.”

“Now… well, I’m stuck with it,” Angus shrugs. “I can’t play wearing anything else, anyway.”

I wondered what the band thought of British audiences – if they reckoned them to be different from Australian ones.

“People are the same the world over,” Scott offers, profoundly. “It doesn’t depend on the people so much as the bands themselves. If a band doesn’t happen, it’s their fault, their fault alone.

“So far in this country we’ve had no trouble. If our receptions haven’t been polite, then they’ve been more so. We haven’t been booed or anything like that. It’s Angus’s knees, you see – the more he shows them, bruises and all, the better we go over. We’ve been really happy with the gigs we’ve done so far over here. But,” he says warily, “I don’t know what it’s going to be like tonight at the Porterhouse, though.”

Actually, it wasn’t too bad at all. Between the time when we’d arrived in the dressing room and when the band emerged to take to the stage at 11.30, the venue had filled up considerably. The closing of the pubs doubtless had something to do with it (this being the age of archaic licensing laws). Indeed the people behind the Porterhouse’s bar appeared more intent on ringing their cash registers than on watching the band, and the punters tended to concentrate on drinking rather than applauding. But it was a hugely entertaining show.

The first time I saw AC/DC at London’s Marquee Club, I was amazed at the good-time atmosphere they created. If your face doesn’t break out into an ear-to-ear smirk during the opening bars of their set you must be a depressive. And even in the decidedly uninspiring surroundings of the Retford Porterhouse, AC/DC were very good indeed.

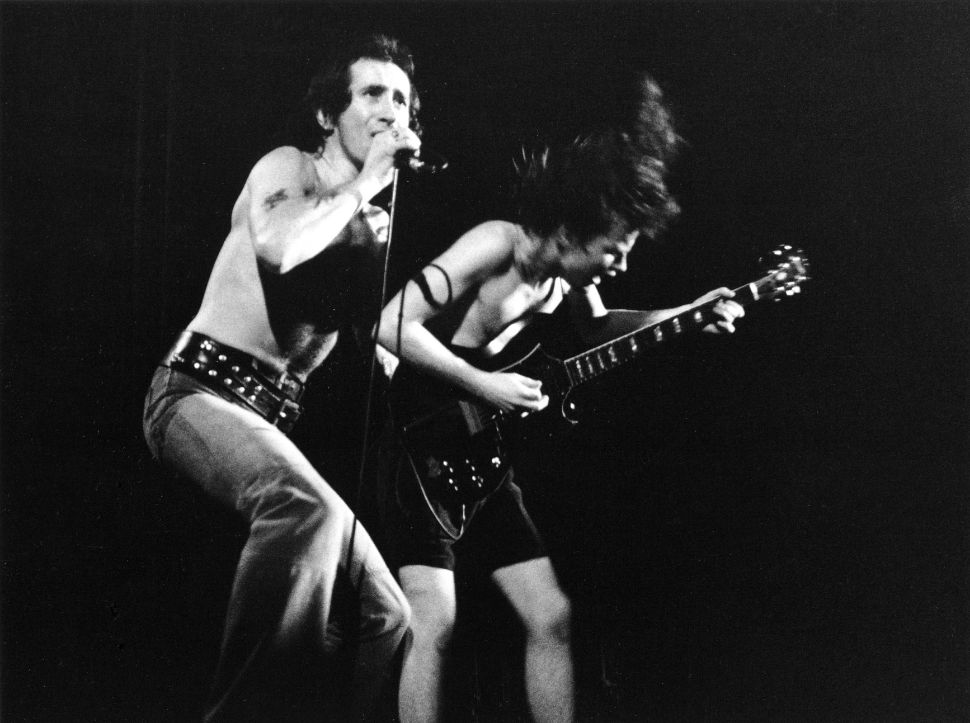

Livewire is the first number, quite appropriate in its way – the first thuds of Evans’s bass acting like a shot of adrenalin, a dose of speed to Angus Young. First his upper lip curls up like a roller-blind, and you half-smile. Then he stoops, peering out at the audience from beneath the peak of his school cap, and you snigger. Then he begins to strut about the stage, and you giggle. By the time the number has built up sufficiently and Angus’s frail arm comes down on his guitar strings with a loud ‘daaauuummm!’… well, you should be chortling with delight.

The next number, She’s Got Balls, presents Bon Scott with the chance to come over as ramrod vocalist and impress his personality on the audience. He isn’t a great singer, but his cheeky, flashing eyes more than compensate for any deficiencies in the vocals department. Well, it’s not so much the eyes as the actual whites of them that come across the most, giving him a leering, lewd’n’proud presence. Scott is in-your-face and bare-chested from practically the opening number, and his pre-Peter Andre six-pack looks as solid as iron.

It’s A Long Way To The Top If You Wanna Rock’N’Roll features Scott on bagpipes, and has some wonderfully clichéd lyrics. Soul Stripper follows, which in turn is superseded by the AC/DC theme tune High Voltage.

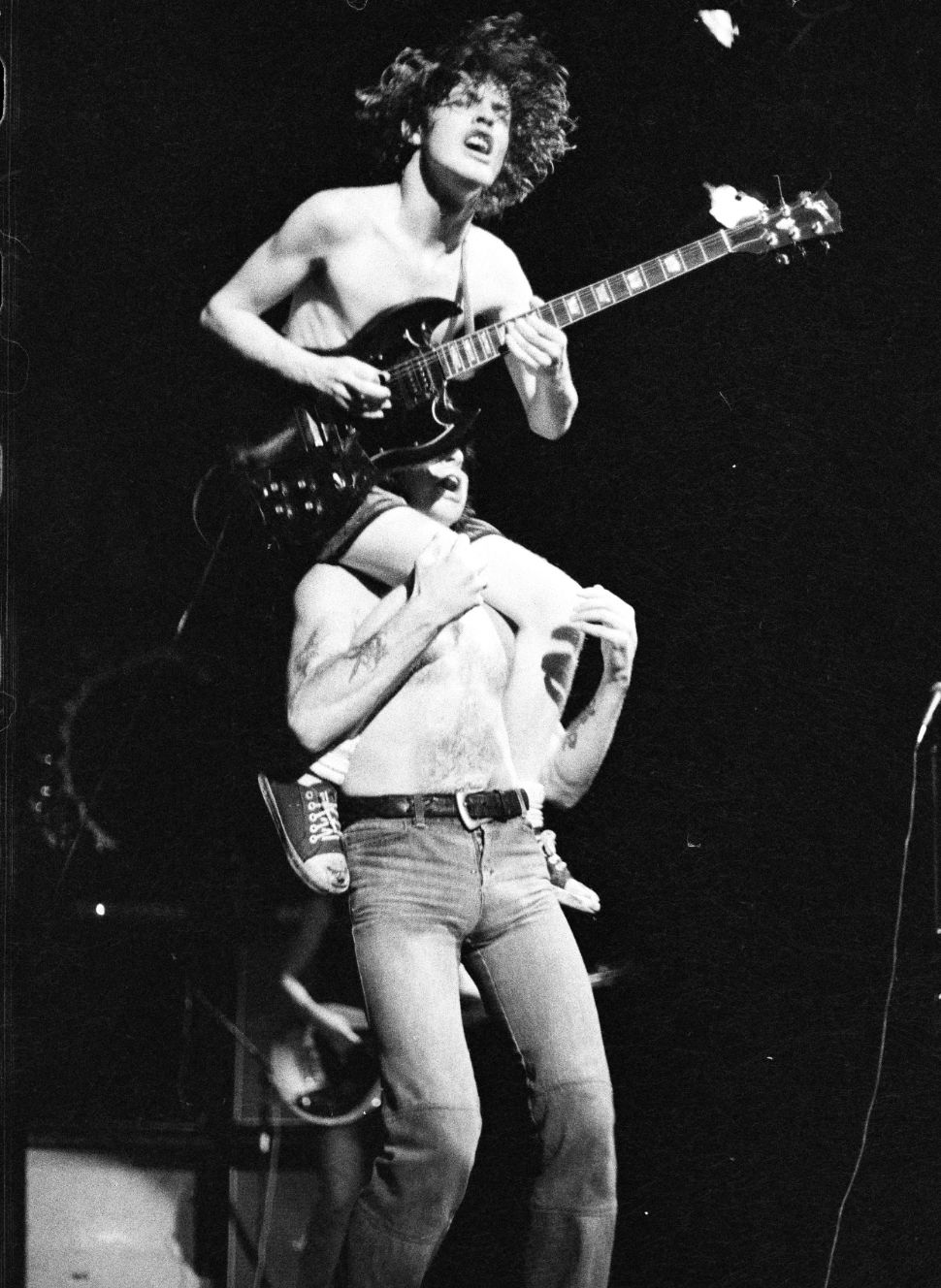

All the while, Angus makes little jittering runs from one end of the stage to the other, leaps up and down, gyrates, sweats, pirouettes, moves, grooves, gets down, bounds, whirls, sweats, gestures, stomps, shuffles, waddles, slides, sweats, flits about, jerks, darts, sweats, lopes, hops, skips, jumps and… sweats. All the while he never misses a beat.

She’s Got The Jack, a little ditty about having sex with a girl who has VD, and which is usually a time for audience participation, doesn’t really get off the ground due to the relatively sparse crowd. But it’s still infinitely enjoyable, including gemlike phrases such as: ‘I searched her mind and I searched her body – but then so did everybody’ and various graphic details concerning ‘a great big empty hole’, delivered by Scott in a suitably despairing wail. Prurience has come to the Porterhouse, and the frontman is loving every low-toned minute of it.

So it goes on, the show reaching a climax when Angus gets up on Scott’s shoulders for a piggy-back ride, and the pair surge off stage and disappear into the bowels of the venue. The audience, it has to be said, looks totally bemused.

Afterward I ask a breathless Angus the question: “How do you keep it up?”

“What?” he replies. “My trousers?”

It’s going to take a good three-and-a-half hours to get back to London, but AC/DC don’t seem to mind. To them it’s just a short trip, a skip around the block. A six-gigs-a-week band in Australia, they think nothing of trundling huge distances across vast deserts and open spaces using only scruffy dirt tracks to travel from one venue to another.

And throughout our trip home Angus is talking, chattering, fidgeting, never still, always wide awake, active and never without something to say or do.

For a while, Bon Scott and I talk some more about the Aussie rock scene. He reckons the reason us Brits haven’t heard of many Australian acts before is because most bands set their sights too low. And when they do decide to try their luck in foreign parts, he adds, they invariably leave Australia proclaiming that they’re going to play in London, Paris and Los Angeles and other cities, and end up being ridiculed when they return because they’ve done none of these things.

AC/DC, Scott claims, left Australia unceremoniously. Realistically, if they do well they’ll be greeted as all-conquering heroes when they arrive back; if they don’t achieve what they’ve set out to do – which is unlikely, with the heavily publicised 19-date Lock Up Your Daughters summer tour coming up – it won’t matter anyway. (The …Daughters tour climaxed with a date at London’s Lyceum with DJ John Peel, of all people, judging a ‘best-dressed schoolgirl’ competition. “I think that’s a contradiction in terms,” Peel said on the night. Oh, behave!)

By 3.40am we’re just past Stevenage. Malcolm Young, Mark Evans and Phil Rudd are all asleep in the back seats. A booze-sodden Bon is slouched beside me, still fingering through one of those damn magazines, toxic fumes escaping from his mouth like smoke from a powerstation.

“What’d be great right now,” he slurs, dozily, brandishing an empty brandy bottle and stifling a hiccough, “would be a huge, comfortable, squashy waterbed, a woman lying right alongside you…”

“…And a big pair of tits in your face,” Angus adds.

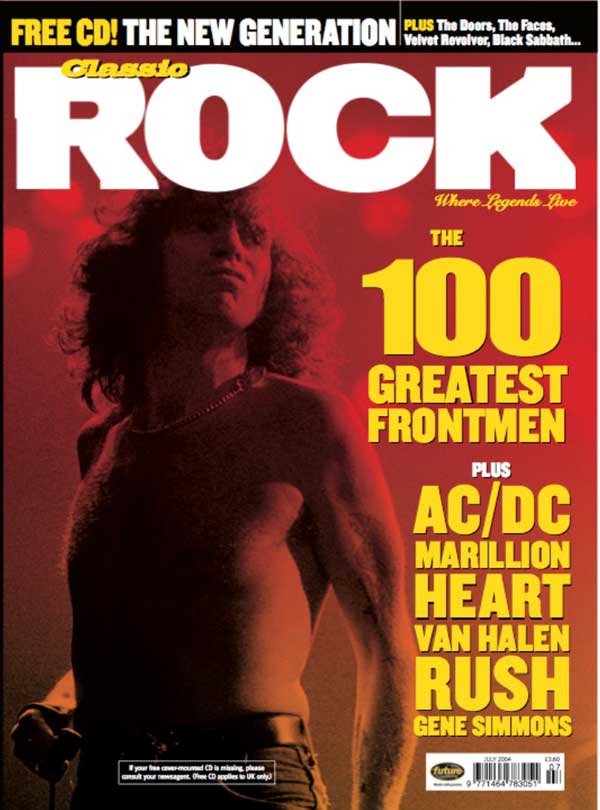

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 68, published in July 2004.

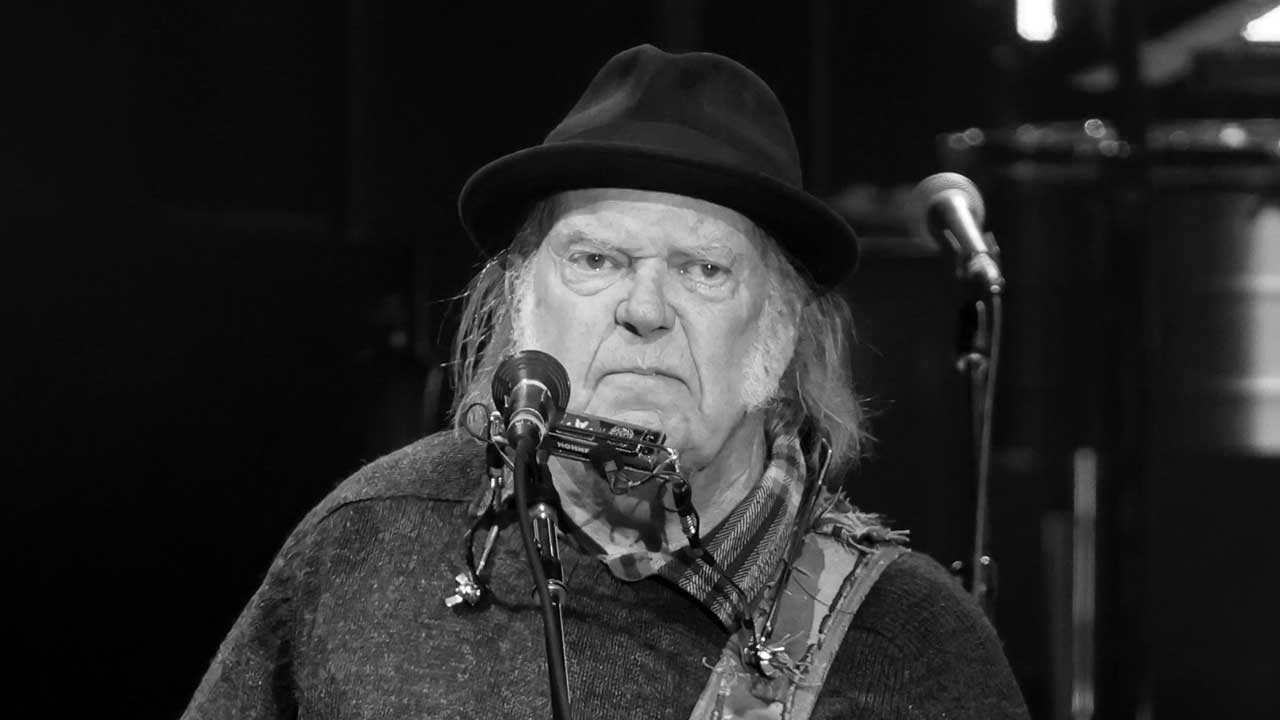

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.