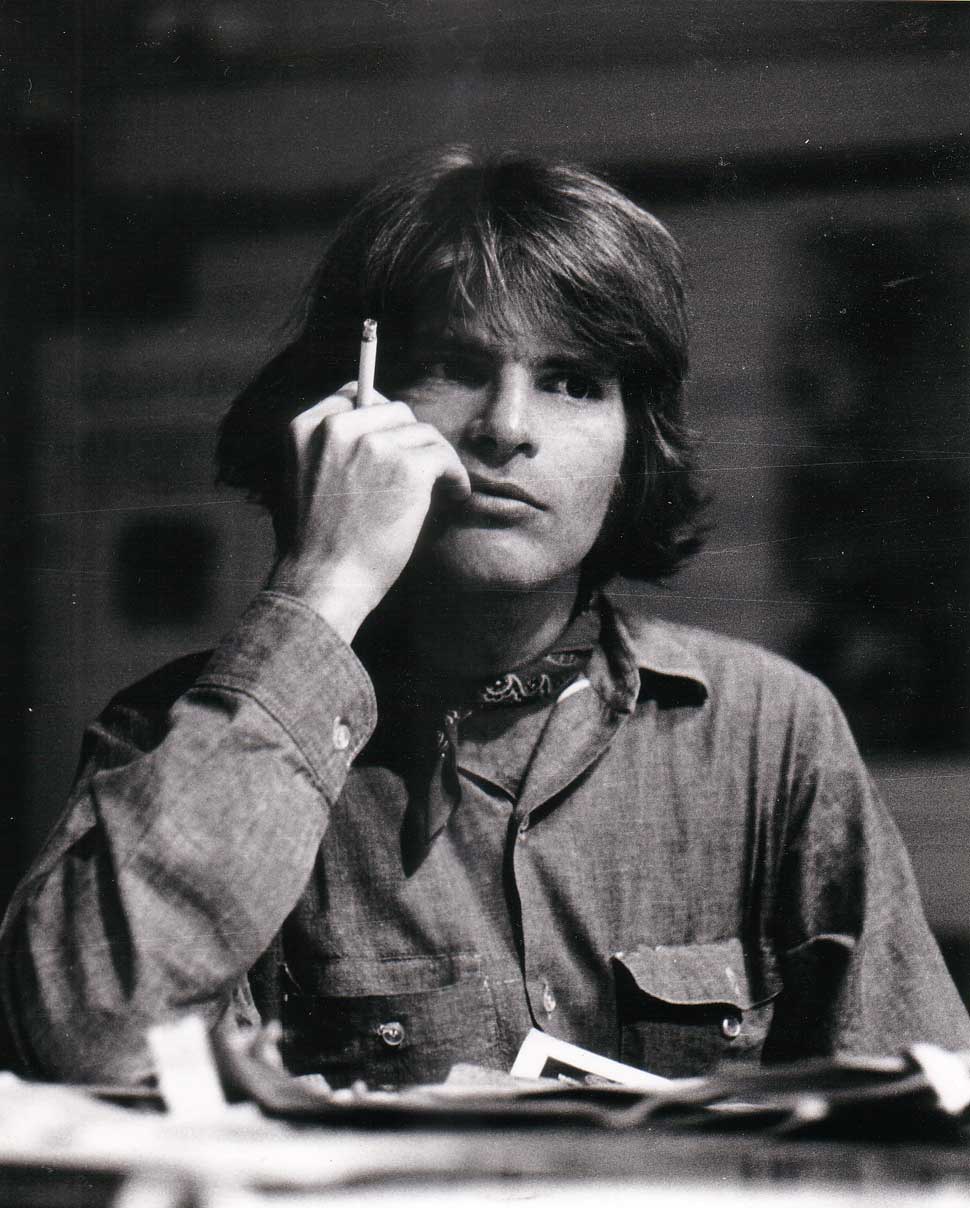

"I'm the one that created all this music, and I don't know that the world always understood that": John Fogerty on closure and reclaiming the Creedence legacy

Now at peace with his past and driven by a renewed purpose, John Fogerty's story is not over yet

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

For more than half a century, John Fogerty lived in a surreal and crippling paradox: he was one of rock’s most distinctive and influential songwriters, yet he didn’t own the rights to the music that made him famous.

The voice behind Proud Mary, Bad Moon Rising, Have You Ever Seen The Rain and Fortunate Son had effectively been locked out of his own legacy. Decades of litigation, bitterness, and silence followed, casting a shadow over one of the most extraordinary songwriting streaks of last century.

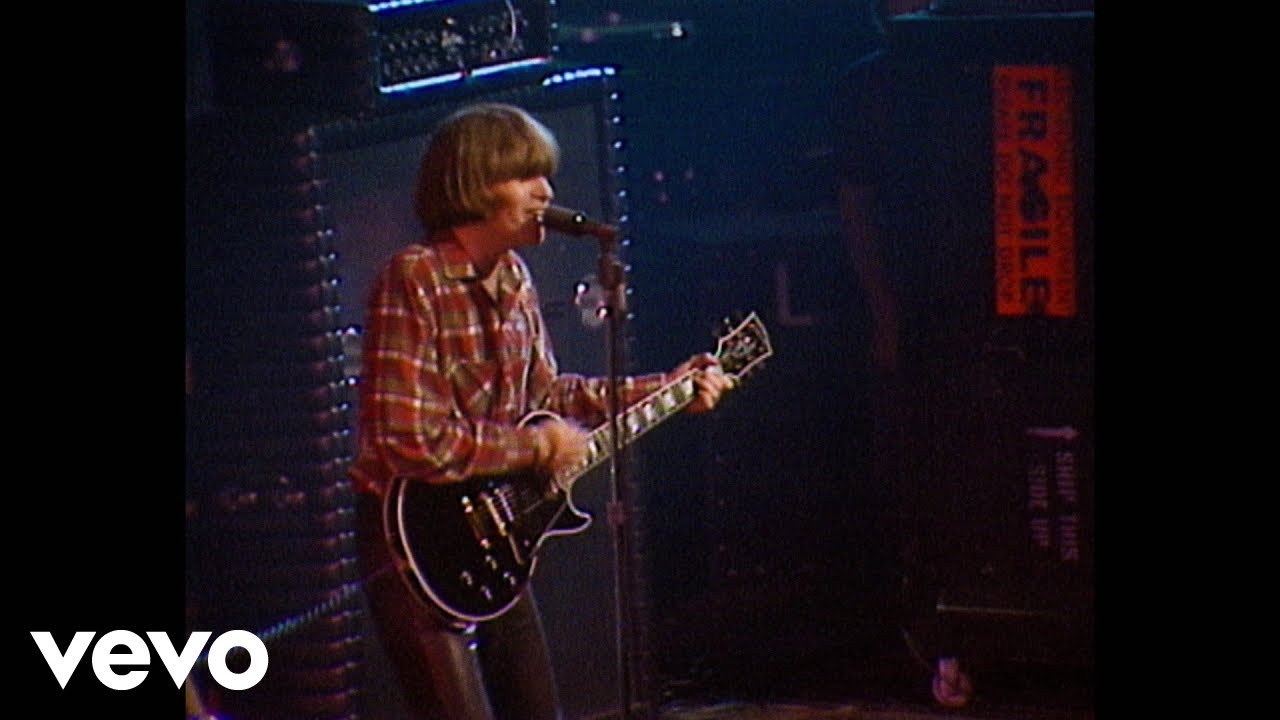

It all began with Creedence Clearwater Revival, the band Fogerty formed with his older brother Tom and two high school friends, Stu Cook and Doug Clifford. Emerging from the Bay Area’s fertile early 60s scene, Creedence evolved from a tight, hard-working local act into one of America’s defining rock bands.

Between 1968 and 1972, CCR released an astonishing seven studio albums packed with sharp, rootsy anthems that spoke directly to a restless generation. In 1969 alone, they released three albums and had four Top 10 singles in the US. For a time, they were outselling The Beatles.

And then, almost as quickly, it was over. Internal rifts and contract disputes tore the band apart. Fogerty cut ties with Fantasy Records and its owner Saul Zaentz, refusing to play his Creedence songs live for years in protest of a deal signed when they were too young to know better.

“Stu was supposed show the contract to his father, who was an entertainment attorney,” Fogerty tells Classic Rock, “but over the years, I’ve kinda wondered if Stu ever really showed it to him.”

At loggerheads with Zaentz, whose ruthless control of CCR’s music crushed his spirit, Fogerty entered a long and painful period of creative exile. There was no reunion. His brother died in 1990. By then, Fogerty had begun the slow process of rebuilding as a solo artist, but the battle over the songs continued for decades.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

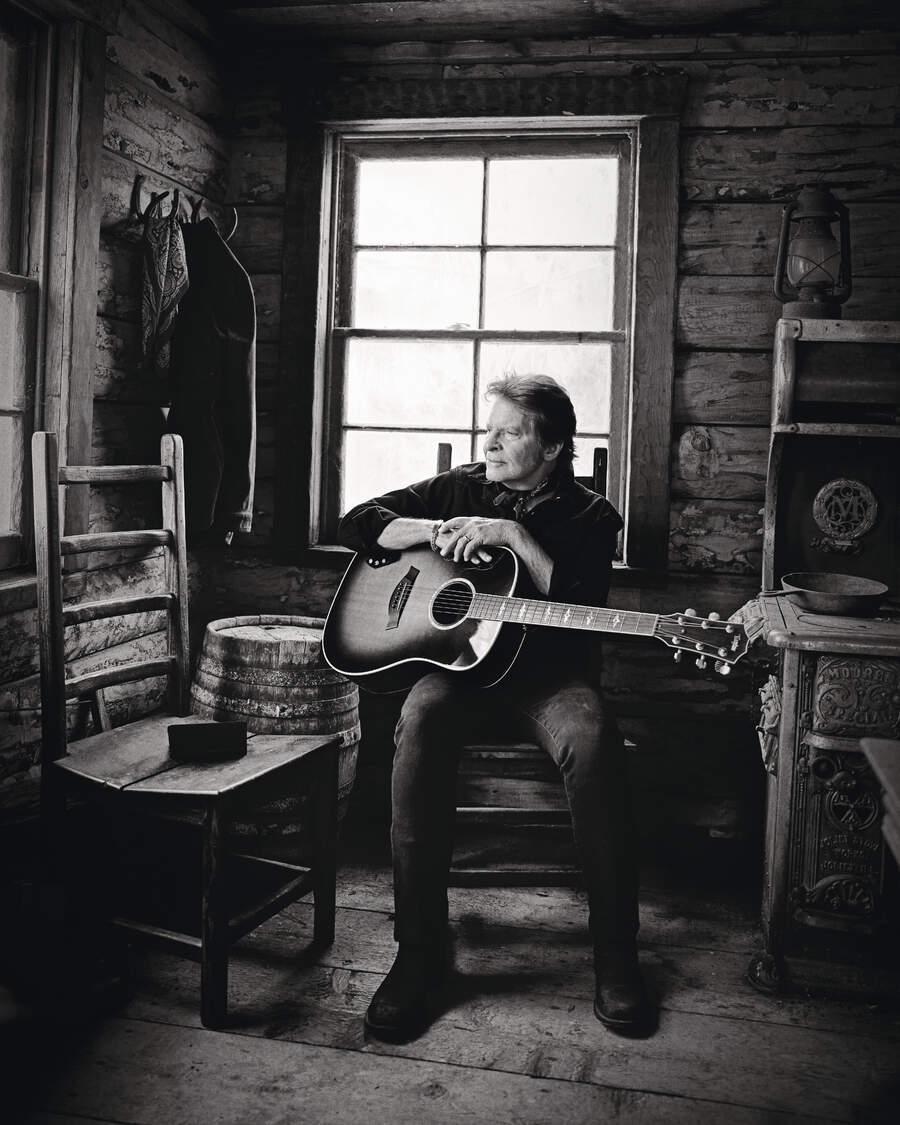

Now, in a remarkable late career victory, Fogerty has finally regained control of his own catalogue. Decades of legal wrangling were brought to an end after Concord purchased Fantasy in 2004, and eventually made good on returning his rights in 2023, freeing him at last to reclaim his own creations.

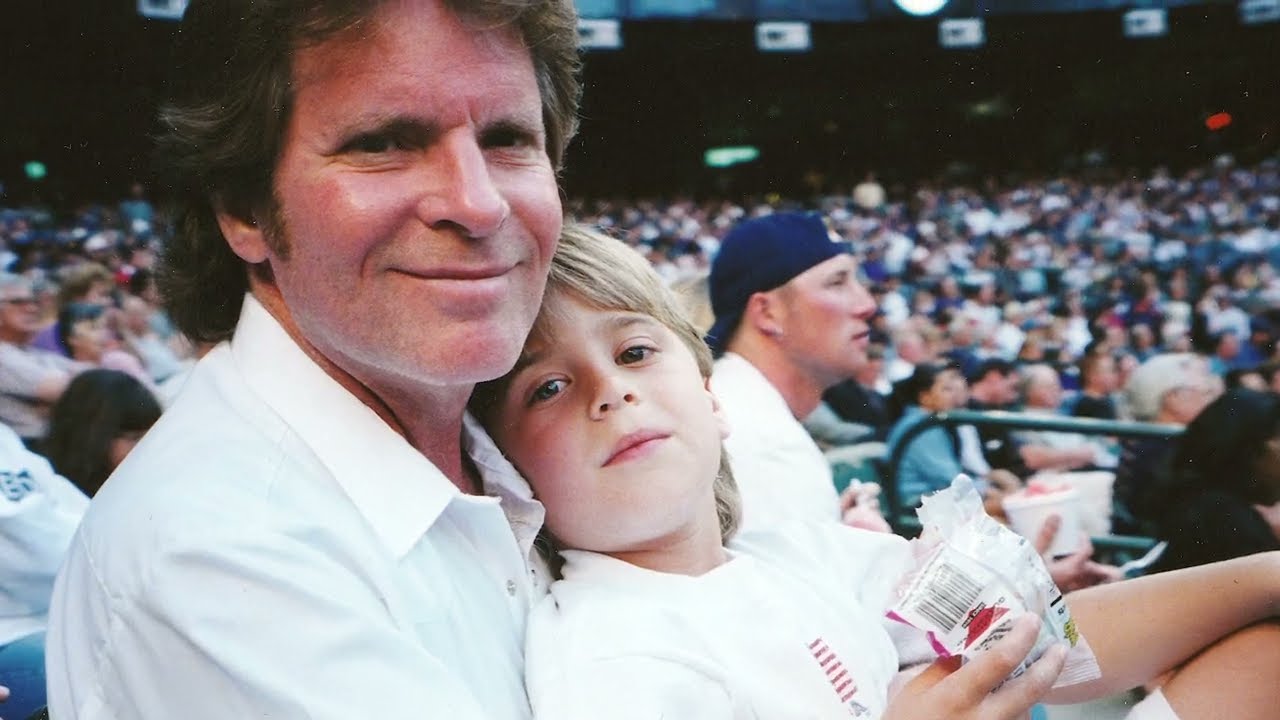

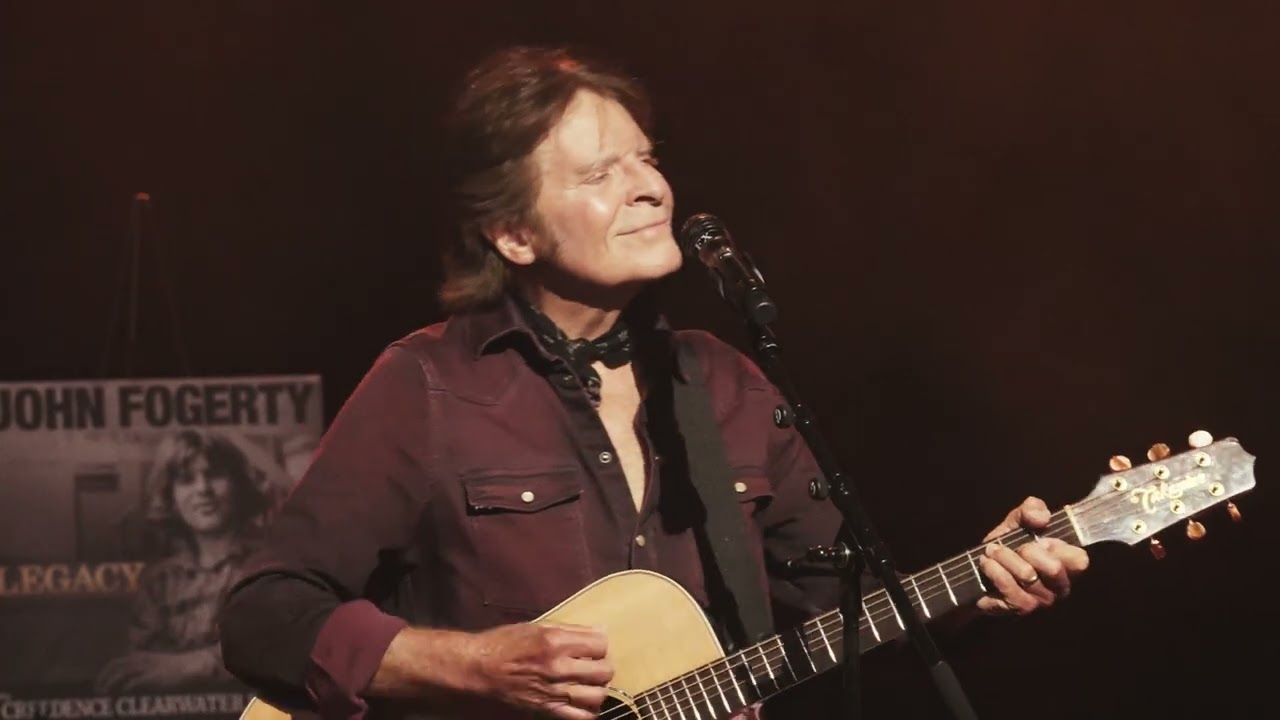

Legacy, his latest album, is both a personal and artistic reckoning. It sees him revisiting and re-recording a hand-picked selection of the songs that once defined a decade of revolt and rebellion. But this time, the performances carry a fresh resonance. That’s because he’s joined in the studio by his sons Shane and Tyler, turning Legacy into something more than just a covers album. Executive produced by his wife, Julie, it’s a family project, a spiritual reclamation, and a joyful assertion of ownership.

Staying mostly true to the timeless originals, there’s a relaxed warmth and a sense of triumph in these new recordings. They’re not just remakes; they’re affirmations. You get the sense this isn’t just about preserving Creedence’s legacy; it’s about redefining it, extending it into the future with family at its core.

As we speak to Fogerty, he reflects on the highs and lows of his long career: from the blue-collar boom of CCR to the acrimonious implosion that followed; from watching others profit from his songs to the hard-won moment of taking them back. Now 80, he remains clear-eyed, good-humoured, and still, utterly passionate about music. At last, he gets to tell his story his way.

After waiting over 50 years to regain the rights to the Creedence catalogue, why did you decide to re-record the songs rather than package up a new greatest hits?

I think some of it was realising I’m never gonna be offered a chance to own the masters – none of us in the band will ever get that opportunity; they’ll be owned by a company, and another company, and it all gets very corporate. So, approaching 80 years old, it just seemed like, ‘Gee, what would I like to do? Well, I’d like to have some recordings that I actually own so that I get to control their destiny,’ you might say. There was a lot of impetus from my dear wife, who kinda envisioned the idea of me having an album made up of re-records. It gave me a project that was actually pretty difficult. It wasn’t like falling off a log.

What were the challenges?

To do it good. To do it well. I realised, ‘Wow, I’m not gonna stand for it being mediocre’. So it meant a lot more work, a lot more involvement, a lot more understanding of it.

You named this record Legacy. Is that word about closure for you, or is it still a living thing, something you’re shaping even now?

Julie came up with that word, and I think it’s perfect. These songs are my legacy, you know? Even though the story has been very convoluted, and half the time when people would talk to me I would look angry or confused or aggressive, it was because there were many feelings I wasn’t able to put a smooth face on. And rightfully so.

I mean, when a guy is tricked out of his artistic creations, I think there should be loud noises going off in the world to say, ‘No, this is wrong!’ I’m the one that created all this music, and I don’t know that the world always understood that. And now that I’ve finally gotten a lot of the ownership – at least, certainly, the publishing ownership of my own songs - declaring that it’s a legacy is very important, because these are, in fact, my creations.

I was alone when I wrote these songs – there was nobody there except me – so I think it’s a perfect word that explains what these songs mean to me.

CCR has always been in the bloodstream of American music, but lately it seems like there’s an even bigger resurgence. Rolling Stone called you “the biggest band in America” in 2024. Why do you think your songs are resonating again so strongly now?

I do believe that I wrote some pretty good songs. You can’t stand at the base of a mountain and try to take credit for the mountain, but I do believe that I did a very good job of crafting and editing and compressing my songs to where there was very little dead weight. They were mostly pretty pure and valid songs. I think that has something to do with it. Certainly the fact that I’m running around creating a lot of noise by doing different things – for one, getting my publishing back.

It became a really big story – there were over a billion views of that story, which astounded me. That means people were interested. I’m completely humbled by that. I think there was some sense that I’d been screwed, and that things weren’t right and, you know, I’m not an awful fella – it seemed like I probably didn’t deserve to have my songs stolen – and so people looked at it as I was kind of the underdog, and I was finally getting something wonderful happen.

I think they were cheering that as perhaps the good guy finally winning. The Creedence music has never really gone away. I think Chronicles [CCR greatest hits collection] has been something like 14 consecutive years on the charts, I don’t know. But I think the current resurgence has a lot to do with my own activity and visibility.

You’ve been active on social media and embracing those platforms to take your music to a wider audience. Do you credit your wife and kids for keeping you plugged in to what’s going on?

Oh, very much so. Yeah, you know, you don’t wanna become the old fuddy-duddy sitting on the couch and petting the family dog and nodding your head, ‘That’s nice’. But not having a clue what’s going on in the world. It’s fun. I look at social media as a fun means of communication and perhaps part of the wider awareness of my music in this modern era.

It’s great that you play with your kids on this album, because Creedence was a family band, too – your brother Tom was in the band. It almost gives the songs a deeper personal connection. Were there any emotional moments in the studio that took you by surprise?

Oh, I think that happened every day. Because the way I kind of explain it is in the beginning, of course, I was just a little boy that discovered music and realised that he loved music, and so I was going forward with the simple joy of a human being discovering what it was in the world that he loved to do, and so I just kept going forward with that, and lo and behold, it turned out that I was pretty good at it. So, not only did I love music, but it loved me back. I got to have this wonderful relationship.

And then things soured; I had success, and the success led to a lot of human interaction that was not happy – it was very hard for me to understand, and in many ways it almost broke me, it was so disturbing. And having then met Julie, and we have our family, and having grown into this relationship and this commitment, life became very good again for me. And then, because of those wonderful feelings, finally being able to face music and have the interest and the energy or the stamina that it took to roll with the punches and the disappointments, and be willing to go into that again.

And now, to find such joy with the music, to me, it’s how it started, and now I am just so happy that things are this way. It’s a great joy to be able to share making music with your family, and that sense of passing things on is just a wonderful emotion. It’s why we become parents, I guess, but it’s a beautiful thing.

Speaking of parents, your mother paved the way for your career by enrolling you in folk guitar lessons as a kid. It’s easy to see a link between the social commentary of folk music and the songs you’ve written. How influenced were you by the music of that era and what you heard at home?

I really am very grateful to my mom for doing that, for steering me or giving me the additional area of folk music that I got to learn from the inside, because she was so fascinated with folk music. I loved rock’n’roll, I loved Elvis, I loved Rock Around The Clock, and The Beatles when they came along, but my mom was so immersed in folk music. She loved Pete Seeger, and passed that on to me, and there were many more. She would take me to these folk festivals that were starting to get organised - especially after the song Tom Dooley became a big hit…

I actually met Pete Seeger when I was 12 years old, and got to go to workshops and hear him explain and show movies about Leadbelly and other singers, so I got an additional musical education besides the one that I naturally gravitated to, that were sort of the sons of Elvis Presley, you might say.

Fogerty met Cook and Clifford as a teenager in El Cerrito, a city just north of Berkeley, California. Calling themselves The Blue Velvets, they played local gigs and served as backing band for John’s older brother, Tom, who had his own aspirations as a singer. After Tom joined full-time, by the mid-60s, the group’s growing regional reputation led them to a deal with San Francisco jazz label, Fantasy Records. The label rebranded them The Golliwogs, a name the band openly despised, and under which they released a handful of singles between 1964 and 1967.

Though modest in chart terms, the material showed promise, and John, increasingly frustrated with the band’s direction and the label’s creative control, was beginning to hone his voice as a songwriter. The group’s momentum was abruptly suspended when Fogerty and Clifford were drafted in 1966, but it was while stationed in the Army Reserve at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, that John wrote Porterville, a song that hinted at a more mature lyrical outlook, and which would shape the group’s new, emerging identity.

Porterville is the earliest song to appear on Legacy. That song was a watershed for you in terms of subject matter – moving away from Beatle-esque pop lyrics. What did it mean to you that made you revisit it here, and what does it represent now?

Well, I think because I was marching around and in a state of sort of delirium and meditation in discovering how to use my mind to position the thoughts into a story – rather than just rhyming cute little rock’n’roll phrases that I’d already heard on somebody else’s record, these were storytelling, and that was kind of a new thing for me.

Obviously I’d heard other people’s stories, but to do it yourself from a story that’s personal… Porterville has a little bit of autobiographical material in it, and then there’s quite a bit of poetic licence, too. But I considered that my first song where I told a story and had a point of view. The first version of Porterville came out as The Golliwogs, as a single, and the recording didn’t quite live up to the song. The song holds up, I just thought that the song was good enough and deserved to have a better recording.

After serving your six months, but still with the threat of being sent to Vietnam looming over you, you became even more determined to make a success in music. How did the experience shift your perspective on your purpose?

Boy, there’s nothing like having something taken away to make you appreciate it, and I suppose what was taken away while you’re in the army is you’re not free, you’re not self-determining. And so, when you get back home and you now have time to decide your own schedule, you also decide to be a little more careful what you spend your energy on, and that was really my determination.

I decided, for one, ‘Wow, I gotta get more organised about my songwriting,’ because I’d always kinda done it haphazard - not really a specific approach - and so, literally, one of the things I did was I went and got a little notebook… I guess the idea in my mind was simply, ‘Well, you’ve got to have a place where you write everything down so it’s all in one place instead of being scattered all over on random pieces of paper all over the place’.

So, I went and got a little notebook and decided that was going to be my little songwriting notebook, and that was a big change in my life.

That determination saw you step up to become lead singer. Tom would later concede, “I could sing, but John had a sound”. When did you first realise you could make that thunderous sound with your voice?

Obviously I grew up being able to carry a tune – I could sing - but around 1964, I started actively trying to push myself to have a more rock’n’roll sort of aggressive voice. It didn’t just come out of me naturally, I actually had to make an effort to push in that direction. I had gone up with some fellas to a place called Portland in Oregon, and we had a two-week job in a little club up there, and I was using the opportunity…

I had a little reel-to-reel tape recorder, and I would record each set every night and then come back and listen to myself and try to determine how I could make my voice get a little more scratchy, a little more harsh, a little more growly… It was a conscious effort to make my voice sound the way I had thought it should sound.

You wrote Proud Mary on the day you received your honourable discharge from the army, which seems to be reflected in the song’s themes of escapism and hope.

Yeah. It’s a strange story behind the song that not many have as their motivation, I suppose. But, for me, the hype of the Vietnam war and the spectre of being sent to the jungle and possibly getting maimed or dying, getting relief from that was a very big deal. So, getting my honourable discharge, I ran right in the house and picked up my guitar, and the first line of Proud Mary is, ‘Left a good job in the city/Working for the man every night and day’. I mean, that’s exactly it. I felt relieved and elevated that I was finally free.

In 1967, just before John’s military service ended, the band finally ditched their distasteful name, and re-emerged as Creedence Clearwater Revival, releasing their self-titled debut the following year. The album featured a breakthrough cover of Suzie Q, which cracked the US Top 20, alongside originals like Porterville and Walk On The Water, and quickly laid the foundation for their signature swampy, stripped-back sound.

But despite this early success, not everyone was happy with how the band was evolving. Tom had been relegated to rhythm guitar, and John’s growing control in the studio – writing, producing, mixing the songs – began to cause friction. By the time they entered the studio to make their second album, Bayou Country, the cracks were already beginning to show.

Given that you were delivering the goods that were propelling the group, what were their main points of contention so early on?

These are really kinda little things, but they’re such big things when you’re 21-years-old and you’re in a band, and the people get their feathers ruffled because they’ve been standing there making music with you casually or whatever for years and years, so suddenly, when one fella starts actually becoming very creative, well, everybody else thinks they can do that too. That’s probably the biggest thing that goes wrong.

By the way, that’s not my responsibility, you know? I was having enough trouble just trying to help myself be creative, so it’s not my fault that the drummer wasn’t able to sing like me. But when people are young and they start yelling at each other, somehow it becomes my fault. ‘Well, you’re better than us and that’s not fair. You should make us as good as you,’ or something like that. It becomes kind of silly.

Things weren’t much better between yourself and Fantasy. Saul Zaentz was boss of Fantasy now, having bought the label in 1967. Were there any signs of what trouble may come down the line with his personal relationship with you?

We’d had a relationship with Fantasy since 1964, when I had walked in the door and asked if they were interested in somebody that could sing and write songs. Saul was the sales rep. He really didn’t have a say-so as far as the creative direction of that record company, that business, but we liked Saul. He seemed to be kinda more normal than a couple of the people that were running the label. They were jazzbos, right? They were really from the beatnik era, and we were just kids; we certainly didn’t understand that.

So when Saul took over and bought the company, we thought that was a very good thing. ‘Oh, somebody that we understand is owning the label now.’ I’m not privy to what’s in Saul’s mind, but you just find it fascinating that a person who’s on the outside, buys a little label for a couple of hundred thousand dollars that’s a jazz label, that’s so far away from the mainstream of rock’n’roll that it’s like being on Pluto, and then lucks into this thing where you’ve got a young man that can write songs and sing ’em, and also produce records. You would think he would go, ‘Oh my goodness, I’ve discovered a golden goose! Wow! Let’s make this the happiest thing we could ever do!’

Instead, his instinct was to put that golden goose in prison so that the golden goose could never get out and go do something somewhere else. I mean, he would have had a wonderful career. Instead, what he did was he shut the whole thing down.

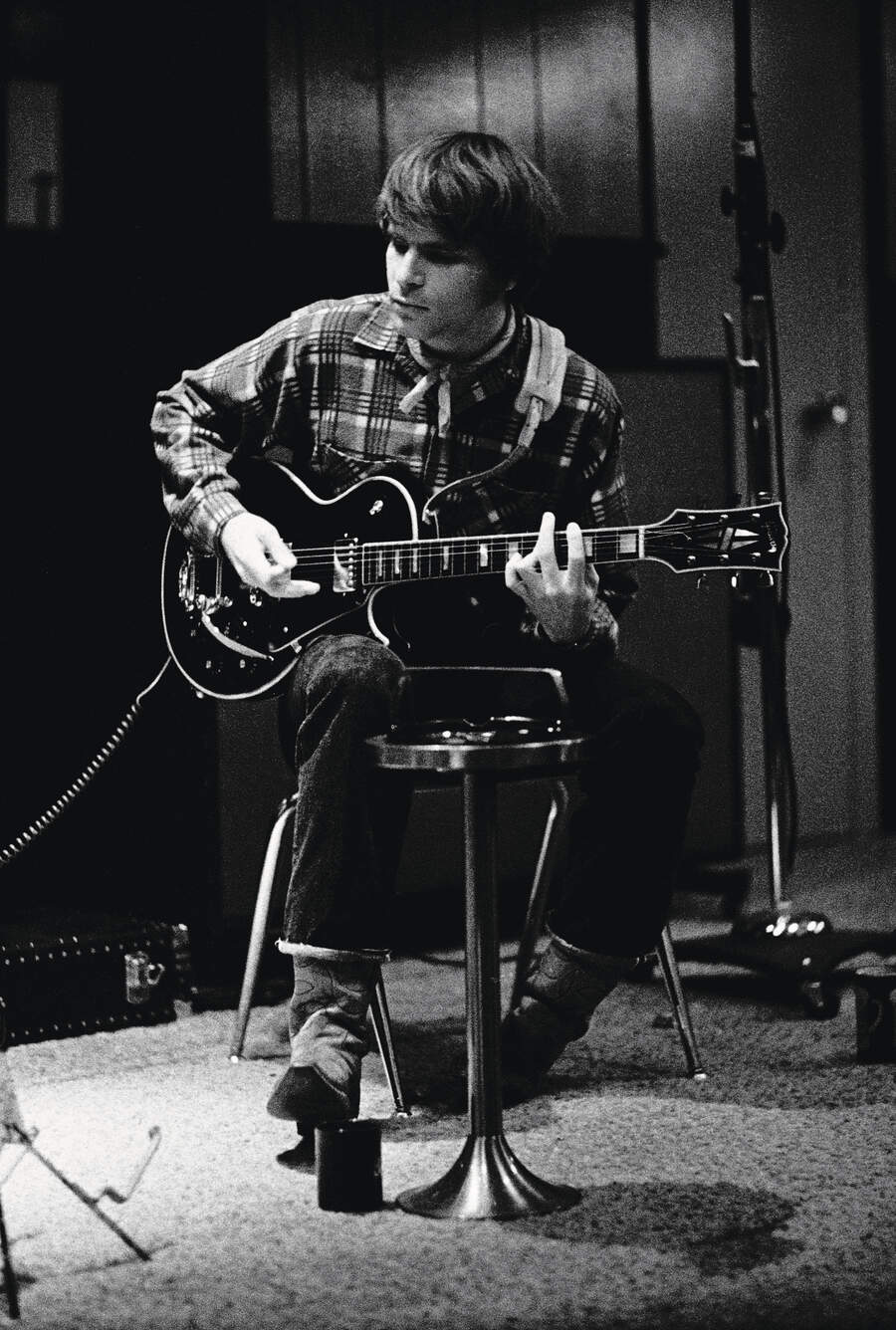

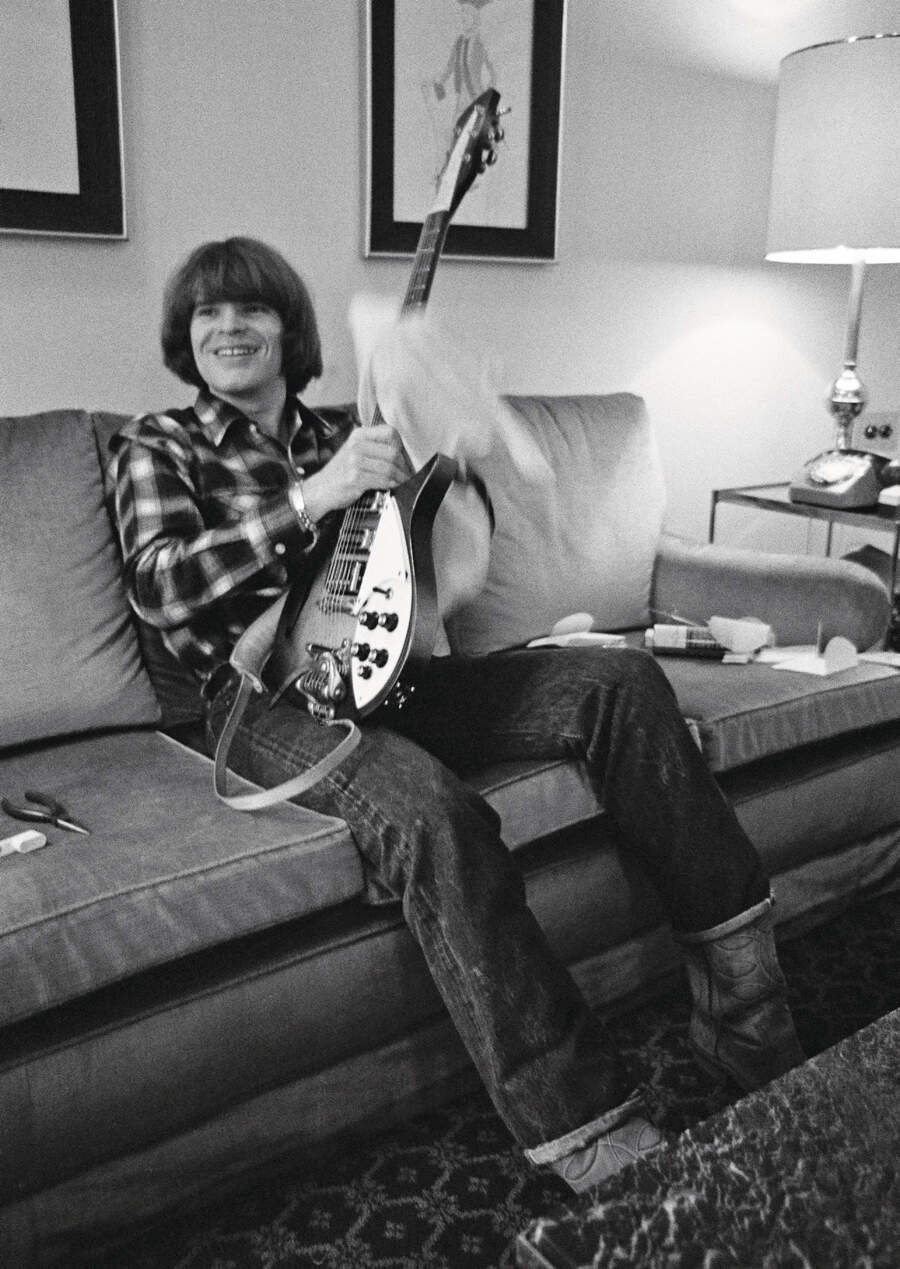

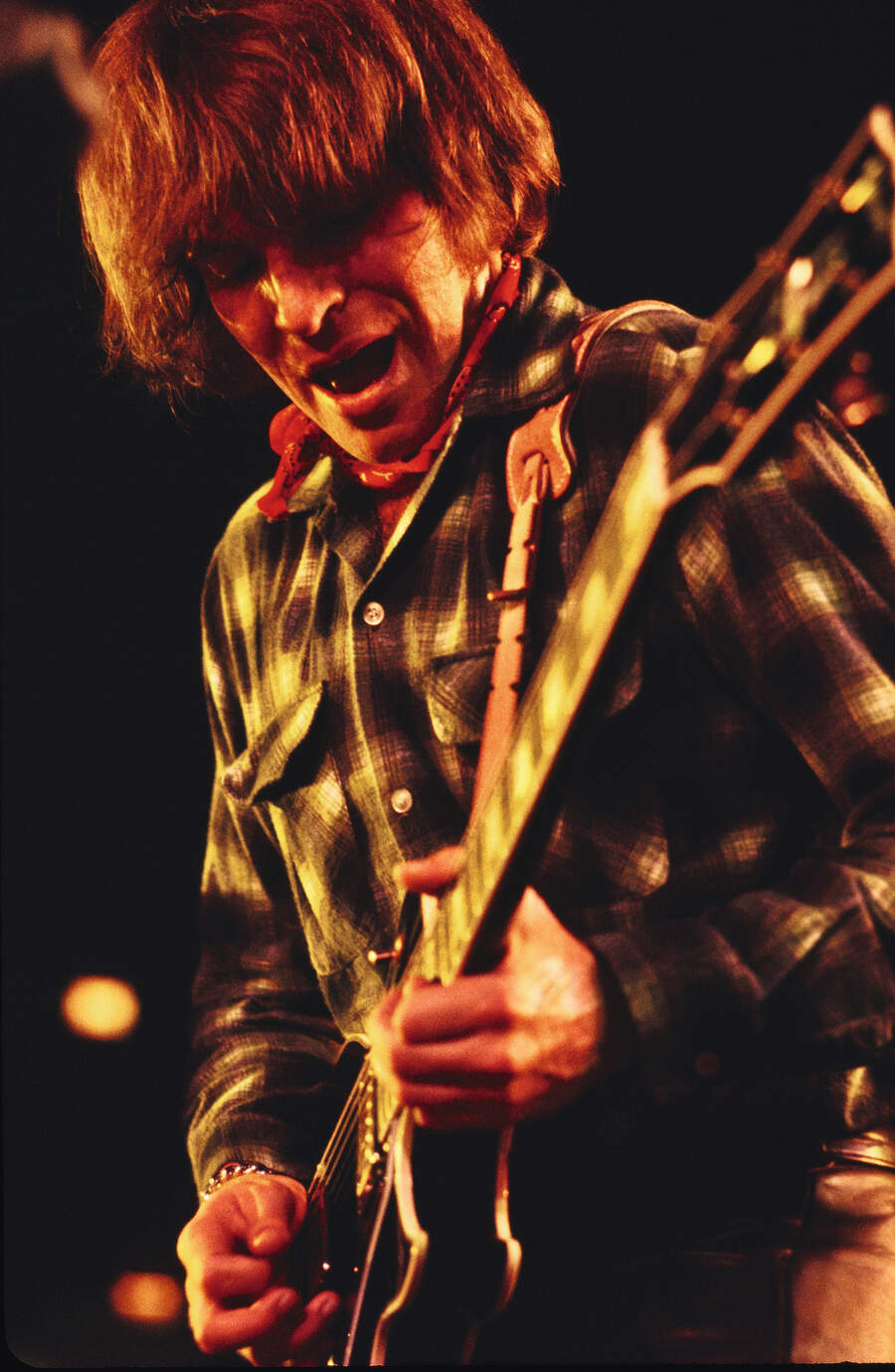

The music that you made has always connected with the people of America. There’s a very working class theme to your music, and even in the way you dressed – plaid shirts and jeans. Was this something conscious you wanted to portray, or was that just your natural persona?

Yes, it was very unconscious. I think I was just trying to show up and be clean and do my job professionally – and I mean that with all straightforwardness. I just decided to wear certain clothes because I liked those clothes, and that was something I understood.

I was not like David Bowie, or even Mick [Jagger], making fashion choices that understood fashion. I’m not here to say I understood that world at all. I really didn’t even care about that. I didn’t think that was important. In fact, when fashion became important later in rock’n’roll, I thought it was a distraction. I didn’t think it held a candle to the music. So, those things were just sort of natural.

Even then, as you say, working class stance: all those words, all that point of view, came out of me, of course, because I was writing the songs, and that was something that I did think about. I had a very well-developed sense of who I was and what I thought this music was for. In many ways like Pete Seeger or Woody Guthrie: the sense that this was from the common people.

In other words, this was not about rich people, or people that owned a lot of stuff - or certainly politicians or anything like that. I was just kind of the everyman doing my job, so I wrote songs from that perspective.

It’s interesting that you use the word ‘job’. CCR’s studio was called The Factory, so it’s almost like you had a place to go to work and create a product to sell. To achieve the level of success that you had required a firm work ethic; you were known to be a perfectionist in the studio, and never let drugs interfere with performance. Were you laser focused on what you wanted to do, and how you wanted it to do it?

Very much so. Once I had written Porterville and had arranged the song Suzie Q in such a way that seemed to really work, it seemed like… I’m not gonna say I understood everything about it, but I certainly had a much clearer vision of how to go about things. Because that’s what you’re mostly doing before you have success; you’re kinda poking around in the pond going, ‘Gee, how does that guy do that? How does he get to be a success like that? What do you have to do to get there?’

And you’re trying to figure things out because you don’t know, and obviously you don’t have success, so once you start to have things working, you’re trying to figure out how to keep doing those things, right? I became, at that point, manic about it. I started staying up very late in the evening – up until 4am every day, writing songs – because for me, I realised what was going to make me different than all the other people who were trying to be on the radio and have a band, was I needed to have more songs.

I had actually made a commitment to myself; at the end of 1968, Suzie Q had been a hit, and I took stock of my situation and I said, ‘Well, gee, we don’t have a publicist, we don’t have a manager, we’re on a tiny little label, we don’t have financial backing… I guess I’m just gonna have to do it with music’. Meaning, if I can create music and supply enough music, it will overcome not having those other ingredients that I thought somebody like The Beatles did have and I was lacking. So I just set about taking care of the thing I thought I could take care of by working really hard.

Despite the brewing tensions within the band, 1969 saw Creedence Clearwater Revival erupt into one of the most commercially successful acts in America. Their second album, Bayou Country, arrived in January, powered by the enduring swamp-rock anthem Proud Mary, which shot into the Top 10 and became their breakthrough hit.

What followed was a staggering burst of productivity: two more albums came that year – Green River and Willy And The Poor Boys – each stacked with hits like Bad Moon Rising, Lodi, Down On The Corner and the furious Vietnam-era protest, Fortunate Son. CCR were suddenly everywhere: on the radio, in the charts, and even on the Woodstock stage – although their set wasn’t included in the original film or soundtrack, due to the band’s displeasure with their aftermidnight performance.

As 1970 rolled in, and with it their celebrated masterpiece Cosmo’s Factory, while the hits kept coming for CCR, many of Fogerty’s lyrics reflected something darker: a rising unease that seemed to mirror the turbulence of the times.

Like the folk songs that originally influenced you, your work became chronicles of American life at that time. Bad Moon Rising and Run Through The Jungle are really infused with this sense of foreboding; looking back, were there clear signposts signalling the death of the 60s? Were those times as fraught as those songs might suggest?

It wasn’t like I was sitting around noticing those signposts. In other words, I think I was swimming in the stream like everyone else. Older, intellectual writers like Hunter S. Thompson, or people like that, would notice those things. I was just a kid of the times, you might say. But I sure loved the sense of foreboding. I just got a chill when you said that. It was like, ‘Yeah, I need to do that again.’

Having written a song like Bad Moon Rising at the time, I was really happy with myself. I hope I don’t come off like a braggart or something, but it was a good song, and I really liked it. Later in life, of course, people could look back and see that sense of foreboding and it makes me proud, but… I think I was more feeling it. You know, Nixon was in the White House, the Vietnam war was going on and all of that… That was where those senses came from.

If you wanted to do it again, just look at the sense of foreboding that’s gripping America now. Ironically, the current President, likely unaware of the song’s true meaning, played Fortunate Son at his rallies. Aren’t you inspired to write anything about this administration?

The answer is yes. I did write a song. It was actually released on January 6th 2021, called Weeping In The Promised Land. Years and years ago, I remember saying something about, ‘Richard Nixon, man, he is a source of endless inspiration.’ I could probably say the same about Mr. Trump. I wonder where are all the other creative writers? I mean, come on, you guys and gals, get out there! There’s a whole lot to write about here. Yes, I am certainly inspired.

You’ve said that Have You Ever Seen The Rain, from 1970’s Pendulum, was really about CCR’s internal problems at the height of your success. Was it emotionally difficult revisiting that song for Legacy?

It’s a wonderful sort of mysterious song. I’m delighted that it has become quite a popular song around the world over time, and it’s in the modern era - it’s passed two billion streams! That means young people are doing it. I’m very, very flattered about that.

Originally the song was about the breaking-up of Creedence, but these days, before I perform the song, I tell the audience that nowadays it reminds me of them, of the audience, of the people who have been singing my songs all these years and keeping them in their heart, and so I’ll say, ‘You’ve been a rainbow in my heart, and this song has a rainbow in it,’ and then I do this song.

Creedence really began to splinter when your brother left in 1971. Did it hurt that the person who should have supported you most walked away first?

Oh, yeah. I never got the chance to reconcile or even figure out what Tom was thinking – if indeed his thoughts were cohesive or understandable at that time. I’m pretty sure he was upset and confused – and I don’t mean that in any demeaning way; I was upset and confused during those times, too – certainly not like an adult would process all that stuff. But at the same time, when Tom left, he also said, ‘Saul Zaentz is my best friend’. That’s such a goofy statement considering what Saul Zaentz was doing to me at the time.

I would have loved to try to figure out what the heck Tom was thinking. I didn’t get to speak to him directly – I was speaking through one of our road people – and so I remember telling this guy, Bruce: ‘Go tell Tom, look, let’s all just take a vacation. Let’s just knock off for a year or two. Don’t make any grand declarations about it, let’s just stop doing this until we can make some sense’.

But Tom didn’t wanna do that. He was adamant about having some definitive action, a decisive event, and so he did that. At that point, then, I’m left with Doug and Stu, and that’s kind of a three-legged stool. Doug and Stu were already each other’s best friend, so I was gonna lose any argument in that crowd. And the only reason I stayed around, remarkably, is I kept walking around going, ‘Well, I guess they deserve a shot,’ meaning a chance to be whatever it is they say they need to do with Creedence, right?

I didn’t think there was a chance in hell that any of them would come up with a good song. That’s just how I felt. I’d known these people for a long time, and I certainly thought that it was career suicide to make the move that they wanted to do, but to keep the band together I had agreed to acquiesce. But then Tom left, so that really threw it out of loop, and then I’m stuck with this thing I said I would agree to. And then, of course, they made their recording and it was pretty awful, and that was that.

The resulting album, 1972’s Mardi Gras, was dominated by songs written by the others, after you agreed to relinquish your songwriting monopoly. As a result, it compromised the strength of the group’s material. Jon Landau in his review for Rolling Stone, called Mardi Gras “the worst album I have ever heard from a major rock band”. You’ve always distanced yourself from that album, but now Someday Never Comes is its only song to feature on Legacy. Do you have a different relationship with that song to the album it came from?

I think it’s a really good song, and I dare say this is probably a better version than the version that was supposedly played by Creedence. Creedence was me and Doug and Stu, and that was disintegrating rather quickly. I suppose I’m not the first band or company or even administration that has found itself in this situation – ‘Wow, we got here because we were trying to do the best quality, the highest level of things, but we don’t seem to be doing that now. We seem to be okaying the very lowest standard of quality just to stick together, or just to hang on to power.’

I guess that’s a natural human emotion, but that last gasp of Creedence was not designed to be trying their best. It was the opposite. ‘Okay, I’m gonna let this guy try to make a record because he demanded to have that right, and I think it’s loony but we’re gonna do it.’ And so we did it, and it was loony, and there you go.

You’ve previously called that situation a “time bomb”, and you must have known that the end was coming, but when that inevitable break-up happened in October 1972, were you confident, because you wrote all the songs, that you would have a secure future, or were you scared because you didn’t know where to go next?

A little of both, I’m gonna say. I knew that continuing Creedence was untenable, because I did not have collaborators. The collaboration ethic seemed to have disappeared, so it seemed like this has to end, even though it’s painful, so that I can somehow get to the next thing.

And I thought that my musicality would help me and see me through – what I didn’t know at the time, of course, was that then Saul Zaentz was going to let everybody else in the band free of their contract, except me, and then hang on to me with a death grip that was overwhelming. It sounds pretty naïve, but I didn’t know the world could be so unfair.

Any hopes Fogerty may have had for a new beginning beyond the confines of CCR were quickly extinguished. Under the terms of his deal with Fantasy, Fogerty owed the label a preposterous 180 songs – a near-impossible quota that effectively locked him into a lifetime of creative servitude.

The clause meant that if he didn’t deliver the required songs, he couldn’t record elsewhere. And if he did, the rights would still go to Fantasy. It was a devastating realisation: the very act of writing songs – the actual thing that had always defined him – had become a trap.

That contract put such a dead weight on you. Did you stop writing completely, or did you just not want to record?

I did end up doing the Blue Ridge Rangers record (1973), and it’s notable that I didn’t write any of those songs…

Yes, it’s all covers of country songs.

For some reason, I really couldn’t [write]. It seemed to be a block… I couldn’t put a song together. But I could still make music and make choices about music, and that seemed to be a device that I could use to get the wheels turning again. And so, that’s what I did. I made the choice to try and play all the instruments. And then I went to Saul and said, ‘Look, I’m having trouble producing music. My soul, my brain is not working. I need to get some sort of relief’.

Much to my surprise, what Saul said - instead of saying, ‘Oh, well I understand. What can we do to help you make more records so that I make more money?’ Which I would have understood. Instead, what he said after I had explained that I was in an artistic crush and I couldn’t make any music, he looked at me and said, ‘That’s not true. The whole history of art shows that the greatest art comes under conditions of oppression and depression’.

I was so thrown by his lack of understanding. I just couldn’t even believe he said that. He had all the people from his level of the record company there at that meeting, and I was there alone. The phrase blew my mind. I didn’t get over that for years. I didn’t know anyone could be that detached and just not understanding of how things worked. Or maybe he just didn’t care.

The following album, 1975’s self-titled John Fogerty was a hopeful effort, yielding the now-perennial Rockin’ All Over The World, but after shelving its follow-up, a disillusioned and beleaguered Fogerty withdrew from the spotlight entirely for almost a decade.

He’d eventually return to writing and recording, but the shadow of Fantasy Records and Saul Zaentz loomed large. The painful cost of buying his freedom to sign with Warner in the early eighties was giving up the publishing rights to his entire Creedence catalogue.

The 1985 album Centerfield marked a triumphant comeback, and included the defiant Zanz Can’t Danz, a thinly veiled jab at Zaentz that led to a lawsuit and a forced title change. Even more bizarrely, Fogerty was later sued for allegedly plagiarising himself, with Zaentz claiming that his new song The Old Man Down The Road was too similar to the CCR hit Run Through The Jungle, a song Fogerty had written.

He ultimately prevailed, but the emotional toll of these conflicts and his predicament would take a deep psychological toll on Fogerty, fuelling a period of alcoholism that began to lift in 1991 after marrying Julie, who became a crucial part of his personal and professional recovery.

He began to carve out a new chapter with solo albums like Blue Moon Swamp (which won him a Grammy), Deja Vu All Over Again, and 2007’s Revival, widely seen as a bold return to form.

Saul Zaentz died in 2014 but you’ve previously said that his death wasn’t the closure you were looking for – instead, it was your creative comeback, spearheaded by Concord taking over Fantasy and trying to make amends, the release of Revival, and the great albums you’d released in the meantime. Was it a realisation that actually it was always your songs that were most important and not revenge?

Yeah. The funny thing is, Saul was such a mean character in my psyche for years, and by the time he passed away, he wasn’t important to me. Julie was important to me, and I had rediscovered my gift of songwriting. Things were going along fairly well, therefore it just was not some big relief that he’d passed. I still think what a waste of time all of that was – Saul, and getting my brother involved in his orbit. It’s just such an entanglement.

Sadly, Tom contracted AIDS from a blood transfusion in the 80s, and died of tuberculosis in 1990. You said earlier that you hadn’t resolved certain issues. Do you regret that you never made it up with Tom?

I don’t leave it as a regret. At some point, I had to forgive Tom. The main issue probably being that Tom considered Saul Zaentz his best friend and said it very publicly – well, that’s a pretty wacky stance for me to have to absorb, considering what Saul did to me. And so, in my heart of hearts, the way for me to deal with it was I forgave Tom.

So that’s not an issue, and some day, somewhere in space when we meet, he knows that now, that I have forgiven that and I don’t worry about it. I choose to think of us the way we were when we were kids and we loved music and dreamed about someday being able to make a record, and those sort of things.

Your relationships with Doug and Stu, which were always fraught since the break-up, ended irrevocably on the eve of the group’s induction into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, after you didn’t let them perform with you that night due to them selling their voting rights in CCR to Saul. Is there no chance of reconciliation with them, despite you now being in a good place personally, financially and artistically?

Ha! For one thing, they’re suing me right now! I just won the lawsuit – just a few months ago, I finally got a decision from the judge – and so then the judge instructed them to pay the attorneys’ fees, which they’re supposed to do, but they haven’t even done that yet. It just seems to be a recurring theme – whenever I put out a record or have something going on, then they sue me. It’s been a cycle for many years. Yeah, that to me would preclude any kind of reconciliation.

So, with no chance of a reunion, Legacy is perhaps our only opportunity to hear ‘new’ CCR music. With that in mind, what do you hope people feel when they hear it, especially the younger listeners discovering you for the first time?

It’s funny, I’m not sure that I understood this while I was making the record, but I’ve been told this now back to me. I’ve heard the word ‘fresh’ a bunch of times. ‘Wow, it sounds fresh!’ I didn’t try to make it fresh, whatever that is. I was just trying to make it good. I was trying to do a good job, make a good record.

But I think the thing you can really feel is there’s joy in the music, because I feel unrestrained. In many ways, during the last times of Creedence, that was a band disintegrating, and things were not feeling all that wonderful every day. Whereas making this record with my family, with my kids, was a beautiful experience.

I think there’s a great sense of joy about the whole thing, and other people have told me that they hear that and feel that.

John Fogerty’s Legacy: The Creedence Clearwater Revival Years is out August 22 via Concord Music.

Simon Harper is a co-founder of the award-winning music and fashion title Clash Magazine, and its Editor-In-Chief since launching in 2004. A lifelong Beatles fan, he has worked on a number of projects with Paul McCartney since interviewing him for a Clash cover story in 2007.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.