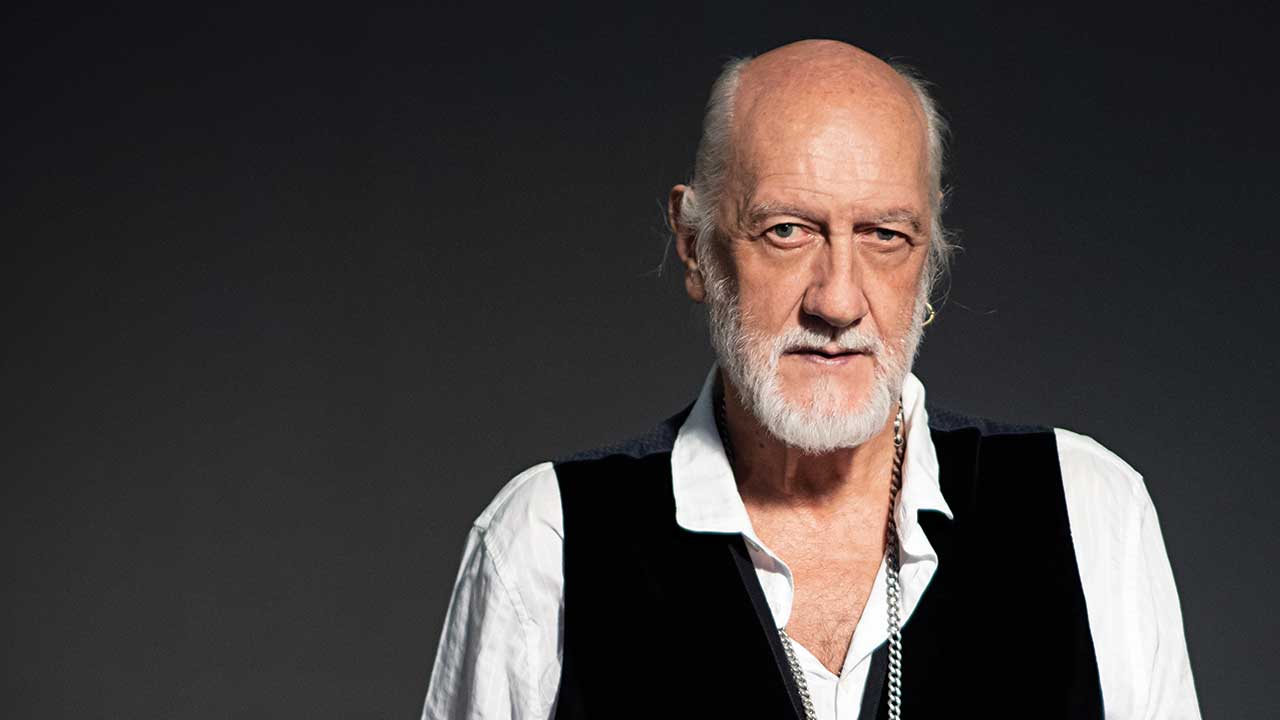

Mick Fleetwood interview: 50 years of Fleetwood Mac

Mick Fleetwood arrived in Swinging Sixties London as a dyslexic school leaver and aspirant drummer – and discovered a world of blues, booze, women and global success

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

You’d never guess that Mick Fleetwood has a starring role in rock’n’roll’s favourite soap opera. Perhaps it’s the island pace of his Hawaiian home, or the relaxation enforced by the pandemic, but a conversation with Fleetwood Mac’s co-founder and drummer is as calming as being in a hammock in a tropical breeze, the fractious life story of his fabled band at odds with his convivial telling of it.

Of course, we shouldn’t be surprised. While he’s no angel, Fleetwood’s abiding presence as referee, peacekeeper and hostage negotiator – always on hand to talk his more mercurial bandmates off the ledge, or hold the line when all seemed broken – is the reason Fleetwood Mac are now nudging past a half-century, with a catalogue of 17 studio albums. Fleetwood might be the groove, and along with bassist John McVie he’s also the glue.

He was born Michael John Kells Fleetwood in June 1947, and grew up across the globe as the son of an RAF fighter pilot. But his school years were torture for a teenager whose undoubted intelligence didn’t tick traditional academic boxes, and today he paints his move to London, aged 15, as his awakening.

Article continues belowA far more gifted thumper than he’ll admit, Fleetwood’s break came when his mentor, the peerless guitarist Peter Green, scouted him for John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, then invited him to form Fleetwood Mac with him in 1967. Swiftly delivering two of the British blues boom’s finest albums – 1968’s self-titled debut and 1969’s third Then Play On – the band seemed set for a smooth ascent. But chart-conquering singles like Albatross and Oh Well hastened Green’s mental health issues, and the guitarist left in 1970, a casualty of fame, acid and unknowable problems in his childhood.

With early guitarist Jeremy Spencer also burning out soon after, the Mac’s tradition of a revolving-door line-up was established. But the band continued, through an underrated transitional period in which guitarist Danny Kirwan found his voice on lost gems like 1972’s Bare Trees, before he too unravelled, refused to take the stage and was fired personally by Fleetwood.

Then came mega-stardom, with the 40-million-selling melodic rock of 1977’s Rumours, an album as famous for hits such as Go Your Own Way as for the failing relationships between lovers Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, and married couple John and Christine McVie. And while in the past decade the Rumours line-up reunited for live shows, the wounds were still raw; Buckingham was ousted in 2018, although the reasons as to why differ according to who you ask.

Through it all, Fleetwood has played on, most recently at an all-star tribute concert to Peter Green, performed at the London Palladium just days before COVID hit, and now set for release as a live album and film just months after the great guitarist’s death last July. It seems a good time for reflection on Fleetwood’s 73 years. And you couldn’t ask for a more genial host.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What are your memories of childhood?

I was completely dyslexic as a child, and I had no acumen – zero – in terms of academic prowess, or any academic worth at all, really. I still don’t know my alphabet now. If you had a gun and you said: “Where’s ‘R’ compared to ‘S’?”, I don’t know. But I certainly never felt less-than, because I was never made to feel like that by my father and my mother. It was never even thought of. They were always completely supportive of all their children.

Actually, we all went into the arts. We were a family where you came to the door and my father would hug you. I remember the first time my father met John McVie, he gave him a big hug. And John told me: “It freaked me out, to have a man hug me.” I said: “Really? Your dad doesn’t hug you?”

How did the drums come into your life?

I think my parents were just happy that I was doing something, versus being completely and utterly useless at school. I had taught myself to play drums in the attic, playing along to Cliff Richard and Buddy Holly records and stuff like that. I left school when I was fifteen. And it was wonderful of my parents, because they sent me off with their blessing, to go to London, with a funny little drum kit and a dream of being a drummer. I had no right to think that I could do that at all. And when I got there I was as happy as a pig in shit.

In London you drifted in and out of various bands. But do you remember your first meeting with Peter Green, and how that changed your trajectory?

We were all in a band together called Peter B’s Looners. Peter Barden, bless his heart, had knocked on my sister’s door because he heard me playing drums in the garage. So I got my first break. I’d never played with anyone at all before, ever. So I was in the band, and we’d lost our guitar player. Greeny had done a short stint with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers when Eric Clapton went to North Africa. But Eric came back and asked for his job back. And at that point, that’s when Peter walked into this little rehearsal room in the East End.

What did you make of Peter Green as a guitar player?

Well, this is where I have my instant confession, which is the first mistake I ever made. We’d already tried a couple of guitar players. But we’d heard about Greeny. He walked in with his Les Paul in a little brown case, almost like a cello case. He plugged in, and I remember saying to Peter Bardens: “I don’t think he’s good enough.” I said: “He keeps playing the same thing.” And of course what I was hearing was the simplicity of Peter’s playing. But I got flustered, thinking: “Is he going to be able to learn all these songs in three days?”

And thank God, right there and then, much to Peter Bardens’s credit, he said: “Mick, you’re wrong. This guy has style and tone and he’s funky as hell.” Of course, Greeny got the gig. And I’ve never scrambled so fast in my life to keep up over the next couple of weeks. I ended up with my mouth hanging open, going: “Oh shit!” Of course, the irony of the story is that I’m the hugest advocate of Peter Green. So thank God I got side-whacked and told to shut up.

You, Peter and John McVie were all in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers

Yeah. They had Aynsley Dunbar, an incredible drummer, technically astounding. So when Greeny said he wanted me in the Bluesbreakers I was like: “What do you mean? I can’t do that!” But very quickly Greeny said: “That’s exactly why we want you – because you can’t do that.” Peter Green had a well-worn phrase that we still use, especially me and John, as a blueprint. He used to say: “Less is more”. And that’s what he saw in me.

It wasn’t long before Mayall fired you. Was it deserved?

Oh, definitely. It’s no secret that me and John McVie drank too much. He was laid off a couple of times for being disorderly. But because he’s such a great bass player John Mayall always took him back. But the two of us was just a bridge too far. Mayall was the first guy who was really organised. He’d tell you where to stand on the corner to be picked up: “You’d better be there, don’t be late.” You always got paid – he had little wage packets. You were taken care of. It was like being part of a fraternity, with a schoolmaster.

I remember being in the back of the old Tranny van. I knew I’d fucked up too much. One night, I’d been really drunk, and I thought: “I’m done, for sure.” So I had the gig sheet, with the next two weeks of gigs, and I’d written notes. And under one of the gigs I wrote: “I’m fired”. And almost to the day, I was. I actually showed it to Mayall in the bus and said: “I think I’m done, right?” And of course that was the case. So I wasn’t with John Mayall very long.

You, Peter and John McVie became the nucleus of Fleetwood Mac in 1967. The story goes that Peter only asked you to join because you were having a hard time?

Yes. I didn’t know that until a few years ago, when I did a really lovely limited-edition book called Love That Burns, which was the beginning of an overture that the Peter Green concert is part of too. And when I was doing that book I spoke to Peter, spent a couple of hours with him. I’ve still got the interview tapes. He was amazingly sharp. And he said to me on the phone: “Don’t you remember, Mick, you were so heartbroken? You were my friend and I wanted you to be okay.”

Because my then-girlfriend had left me and I was totally broken-hearted. I talk too much, but when Peter said that, I stopped. He didn’t know it, but I actually broke down in tears. Because it was just so indicative of my relationship with Peter. It had nothing to do with music, actually, at all. Anybody can play drums.

He just basically said: “Screw it, this guy is so down in the dumps, I’ve got to pull him out.” It actually meant so much more. Of course, he fully intended John McVie to be there too. Y’know, the band was called Fleetwood Mac. Just the name demonstrated Greeny’s lack of ego and his generosity.

There’s sometimes the perception that you left Mayall in the lurch.

A lot of people always thought there was some plot in the ranks of the Bluesbreakers. Because three out of the four people that formed Fleetwood Mac – Johnny Mac, me and Peter – came out of that line-up. And everyone very often thinks that we planned to dump John Mayall and form this band. Absolutely not true. We had no idea. I went. Shortly after that, Peter got a hair up his rear end about wanting to move on, and he left. That’s when he formed the beginnings of Fleetwood Mac with me. Then we wanted John McVie to join. But it was not a plot at all. In fact Peter had no intention of doing anything at all before he approached me.

Jeremy Spencer joined on guitar for Fleetwood Mac’s 1968 self-titled debut. How do you feel about the so-called Dog And Dustbin album now?

Oh, I love it. We were like pigs in shit, doing exactly what we wanted. Peter was so selfless. Even back then he really didn’t want to be ‘the dude’. He didn’t want to be a Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton or Jimmy Page. There’s a whole fraternity of amazing guitar players, and Peter was one of them. But he didn’t want to be any of the super-gunslinger guys. Just think how heavily Peter handed that first album to Jeremy. Jeremy is that album, in many ways, with his Elmore James stuff. Peter loved just sitting back, playing rhythm.

How did the band evolve with 1969’s Then Play On?

By the time we made that album Peter was crafting these incredible songs. But that’s also when Danny Kirwan joined, and Peter gave him half the album, just integrated that sensibility, didn’t even think about it. Danny brought an incredible amount of talent into the band, by the way. He used to sit at the front and watch us play, almost like this funny little schoolboy. He had this band Boilerhouse, and they used to play with us sometimes, and we were like: “This kid is fucking unbelievable.”

Often he gets completely forgotten. But he had the complete touch, and unbelievable vibrato, like a Django Reinhardt, pure as snow. At that point I knew that Peter was getting a little itchy. Jeremy had no intention of ever going away from strictly what he loved to do, playing Elmore James. Peter was going forward, starting to write more. So it worked out fantastically when he found himself a compadre in Danny, who was really creative, and did all that lovely work on Albatross, which is really all about the harmonic tone. Looking back, I think it’s fair to say that a lot of this stuff was groundbreaking.

When did you first get the sense that Peter was struggling?

Well I don’t think we ever did. We got the sense when it was too damn late. And I don’t think we would have been, in retrospect, equipped to do anything about knowing how to help him anyhow. He intimated that he was done. We were on a tour in America and he said: “We’ve got to give all our money away.” Of course, we didn’t know that his illness was starting then. And he disowned himself. Disowned what he’d done. Said that he’d stolen everything he’d ever created.

Of course, it’s nonsense. But then suddenly it was like: “Oh shit, he’s fucking leaving.” We were down on our knees, going: “What’s going on? How can this be?” Especially me. He left very responsibly. He didn’t dump us. Then came the real damage, which is public knowledge. And the new tribute concert is so not about that, it’s about celebrating him, so I don’t want to talk too much about the woes of what happened. I think he was just so not equipped to being such a powerful entity. And then the drugs… He was one person who didn’t need any of that shit. He was so sensitive anyway.

Looking back now, what’s your take on Peter’s exit?

Fleetwood Mac’s story is all about survival. What you would say about Peter was, he was not able to survive. I’m just saying that he was not equipped. He was not equipped for that journey. For whatever reason, I may never quite know. But it certainly was about a gentleman who was incredibly sensitive, and had been hurt as a young boy. Y’know, being Jewish in the East End of London, he’d had a rough time, way more even than the stories he would tell me. I don’t think he ever properly got over that.

You’ve said that after Peter left, the band was floundering.

Now I look back on it, when we made Kiln House [1970], the first album without Peter… I actually really love that album. But Danny was pressured. Jeremy had not really made huge inroads to writing. So we went into Jeremy’s rock’n’roll world. We just kept going. I was devastated when Peter left. It was so catastrophic.

We were able to continue in this shaky way, and then we brought Christine in, and musically that really helped. And later on, with [guitarist] Bob Welch, that was actually a great period, when we worked a lot in America. We were a working band and we were surviving and it was okay. But none of that would have happened if we hadn’t learnt that lesson. It was such a catastrophe when Peter left. But we got over it, and somehow we muddled through.

So many things have happened since then, with people leaving and coming – it’s been our history, really – and I don’t think me and John would be keeping the company store going had we not had a really brutal survival lesson right at the beginning. When all these other things happened, we just thought: “Well, we’ve done it before, so we’ll do it again. Nothing can be worse than losing Peter.” That’s how I think we’ve survived. And we’ve never not been there, me and John. Ever.

Things went sour again in 1973, when you cancelled a US tour after discovering your wife Jenny was having an affair with Mac guitarist Bob Weston. How painful was that?

It was painful for everyone, I’m sure. But you have to take responsibility. I don’t even look at it as a betrayal. A lot of these things we’re touching on happened because we weren’t equipped. I wasn’t equipped to know that Peter was in trouble. I wasn’t equipped to think: “You’re having too much fun and you’re not paying attention to your family.” Me and Jenny got back together. We were able to carry on.

Why do you think the Rumours line-up had such incredible musical chemistry but such terrible personal problems?

For many years it was relatively A-okay, with all its ups and downs. But we had four people that were highly involved. John and Chris were married. Stevie and Lindsey might as well have been. And the pressures of this journey that we took, they came unravelled. I think a lot of preordained beginnings of problems were just laid so bare and raw.

One wonders if it wasn’t for Fleetwood Mac, John and Chris probably wouldn’t have broken up. But we had incredible times, even when everyone was broken up. Lindsey would say that none of us got the chance to mourn the break-up. Which was very true. And I think eventually that came back to haunt the relationships. But musically there was huge loyalty. It wasn’t about “Let’s make lots of money.” There was a real passion, that this was not going to stop what we were doing.

What was the scene like while making Rumours at The Record Plant in Sausalito?

Well, me and Jenny had broken up. So all five members of the band were in the shit. Emotionally, totally fucked-up. But I don’t remember it being dark and black or that hideous. Believe me, I’m pretty damn sensitive, I would have known. It never reared its head in that way. As the sort of father-confessor that I probably represented in the band, especially back then, I never had that feeling during Rumours of the troops coming to me, and me shitting myself, thinking: “We’re done.” To outsiders it looked that way, though.

I was sort of managing the band at that point, and Warner Brothers used to phone up. We were like the golden goose, about to lay another golden egg. They were petrified. And I’d say: “No, we’re not going to break up.” Anyone with a blueprint would say: “There’s no way these people can survive this. It’s gonna blow.” But I never had that [sense]. I knew things were awkward, and went up and down, but it was never like: “I’m done, I’m fucking leaving.”

It was always back in the studio next day. Again, none of us were equipped to psychoanalyse what was going on. I think the more unhappiness there was emotionally, the more everyone grabbed on to what we were doing.

Your golden rule was to never get involved with bandmates. But by getting involved with Stevie you broke that rule.

Well I think we all did. That’s why John came up with such a great album title for Rumours. He said: “This is like a fucking soap opera”.

You were basically writing about your own failing relationships, weren’t you?

I don’t think Lindsey sang the vocal to Go Your Own Way in the studio until just before the album came out. There were some other words or something.

Why do you think it was always you who had to take the role of peacemaker?

I think it came from the way I was brought up. My father was really good with people, and I like to think that I’ve inherited some of that. Also, I think it’s the fact that John has always said – and still does – “You sort it out, let me know when they’ve all calmed down and I’ll come and do the tour.”

I think a lot of it comes from a type of insecurity. If you’ve got a little green gremlin on your shoulder asking: “What else are you going to do, Mick?” then you’ll go: “Well I’d better make sure this thing doesn’t stop.” So the extra effort was probably through a type of insecurity, of “What the fuck else am I going to do?”

How difficult was it to bounce back from bankruptcy in the mid-eighties?

Not really that difficult. It didn’t really do anything to me. It truly didn’t. And I put that down to the way I was brought up. My father would always say: “Don’t forget, Michael, like anyone else, you get up in the morning and take a shit.” He’d also say: “It’s a shame that everyone in the United Nations isn’t just sitting there naked, then they’d start talking to each other.” I never felt that my life was over. I think I was fairly anaesthetised in that period. I think I just picked it up and kept going.

By the time you got to records like 1987’s Tango In The Night did you ever worry that Fleetwood Mac had strayed too far from Peter’s original vision?

No. It’s odd when you look at it on paper. But it was so gradual that me and John had no sense of betraying something or liking something more. Having said that, I mean, I love all the stuff we’ve done. But if you really put me in the corner and said: “You have to make your mind up – what was most important to you?” I would have to say that it was the period with Peter Green. And the reason for that is that’s where I learnt to do my shit.

You let Bill Clinton use Mac’s Don’t Stop in his 1993 US presidential campaign.

Well, they used it without asking. But we liked him, and it took a natural course, and became a national anthem. Still is. But we didn’t plan that. We had nothing to do with it at all. But we didn’t want to end up suing them or something. We went and played at his party. One member of the band wouldn’t have voted for him, but the rest of us did.

Fleetwood Mac’s last studio album was 2003’s Say You Will. Why no more?

We just stopped. Christine had left. At that point it would have been down to a dysfunctional band. Could there be another album? I think there’s been a thousand and one times when the answer would always be ‘Yes’. My wish, of course, is that there would be. I think this period now is interesting. Everyone’s doing their own thing. So I don’t know. But looking at the state of the nation, or whatever you want to call Fleetwood Mac, I have no qualms or regrets.

If it ends, I think we’ve done A-okay, and we’ve left a lot of great music behind. There is a band. We’re not broken up. There’s some incredibly talented people. But time is wearing on. I don’t know whether John wants to do this any more. But then he’s done that a couple of times. He’ll go, like: “Oh, I’m bored shitless…”

Do you think things could have been handled better with Lindsey in 2018, when he had to leave the band?

No, I really don’t. I’m in touch with Lindsey and we had a great conversation, and it was understood that basically the dynamic for both Stevie and himself had really worn its way so thin… it was just really not a happy situation, and it’s not good for either of them. We couldn’t endure going on. And at that point, in many ways, believe me, even I’m going: “We’re done.” And that’s the best way to describe it. There was just so much unhealed emotional content.

Again, no one was equipped to keep it going. It was just too much. So that was that. One thing for sure is that Lindsey’s work with Fleetwood Mac is faultless, and such a major part. In his own way, like Peter Green, he’s unbelievably talented, hugely invested. Also, everyone has had their own story. There’s not anyone – apart from me and John – who hasn’t left this band for many years. Lindsey left for, like, twelve years – and came back. They’ve all done it.

You seem to have come through your career having remarkably few demons.

Fundamentally, yes, I think so. I truly don’t think that I’m in sufferance of a blame game or an extreme woe-is-me. I think there could be a slight tincture of foolhardiness, certainly in my private life. I have some regrets that my undying dedication blinded me from things that were close to me, in relationships and time spent with partners. But I’ve always loved the life I live, and I still do, with all the ups and downs. So the answer is I’m still me, I’m still Mick, and here we are.

Why was it so important for you to honour Peter with the tribute concert?

Well, I’ve really been wanting to do this for a long time. And it went on and off the radar. Time crept on by, and to me, I really felt that the beginnings of Fleetwood Mac were quietly fading away. Because the band did change so much. With the Stones, even though there’s been some changes, it’s still very much the Rolling Stones, and the principal players and the energy behind the band. We changed so much that the beginnings of this band, I felt, was quietly in danger of fading away into obscurity.

I wanted people to know that those days were really a formative time. I wanted to do this to really say: “This is how it started.” So I’m really blessed that we were able to pull this off. If this show had been five days later, it wouldn’t have happened. The players wouldn’t have even got on the plane to England. And then it probably would never have happened.

The concert film must have added poignancy, given that Peter died shortly afterward in July?

Yes. Peter passed away very suddenly, with no pressing health problems that were visible. He passed away in his sleep, he wasn’t ill or anything. He just went away. Which was very sad, but also typical Peter in a way. He had no ego at all. He knew I was putting the show together. He said: “Oh, that’s cool.” And I’m like a little pet dog, going: “Aren’t you excited?” He just wished us luck.

There was a thought that he might turn up.

We had his seat ready, should he change his mind. Whenever I play in England I always go: “Well, you come if you want to, Peter.” And he did. A couple of times he came to Fleetwood Mac shows at Wembley. He didn’t come to this show. But he was looking forward to seeing the footage. That didn’t happen, sadly.

How did it feel to be on stage with Peter’s iconic Gibson Les Paul again?

Well, Kirk Hammett bought that guitar of Peter’s about two years ago. He lives in Honolulu, so for the concert he came over to rehearsals here in Maui, and he brought Peter’s Les Paul. He uses it as a work guitar, which is great. My nephew said: “Uncle Mick, it’s just dawned on me. Do you realise that you haven’t been on a stage with that guitar for way over fifty years?” And I went: “Fuck!”

It was so synonymous with Peter, and that guitar is so famous, and the tone of Peter Green. And Kirk, I have to say, played his fucking ass off. We decided in rehearsals that his performance of The Green Manalishi with Billy Gibbons should finish up the show. There’s no coming back from that song, y’know?

Do you feel like a septuagenarian?

No. And I worry about that. Because there’s a mirror in the hallway, and I’ll check myself out and say: “Fuck.” I swear to God, you think you’re about thirty-two years old. And I think that could be a bit of a worry. Because I’m seventy-three. I’m healthy, touch wood. But it’s the mental and the emotional part of me. I won’t mention who they are, but I know several people who are about my age and they’re like children. And I think I’m one of them.

Not all the time. But I’m so comfortable talking to people that are eighteen or nineteen years old. So I think I am, to a fault maybe, very young at heart. I can make a transition where I will rein myself in. But I don’t like those moments when I rein myself in. Generally I probably feel like I’m about thirty-two years old.

How does it feel when you look back over the story of Fleetwood Mac?

This is an extreme story. We could be talking for another twenty hours and we still wouldn’t run out. And if you put it down on paper, you’d say: “This isn’t true, there’s just no way.”

It’s fairly unusual. It’s fairly unique to find a story about a band like this, that’s involved with partnerships and women and tragedies. But with all the twists and turns, it has worth been a damn. And the music speaks loud and clear.

Mick Fleetwood & Friends Celebrate The Music Of Peter Green… is released on physical formats in April via BMG. The show will also be streamed on demand.

Henry Yates has been a freelance journalist since 2002 and written about music for titles including The Guardian, The Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a music pundit on Times Radio and BBC TV, and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl, Marilyn Manson, Kiefer Sutherland and many more.