“If they are going to stick so violently to the form, then the standard of content must get a lot higher”: Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Free and the forgotten godfather of British blues who helped them all get off the ground

There were bigger and more famous British blues musicians, but few were as influential as the late Alexis Korner

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

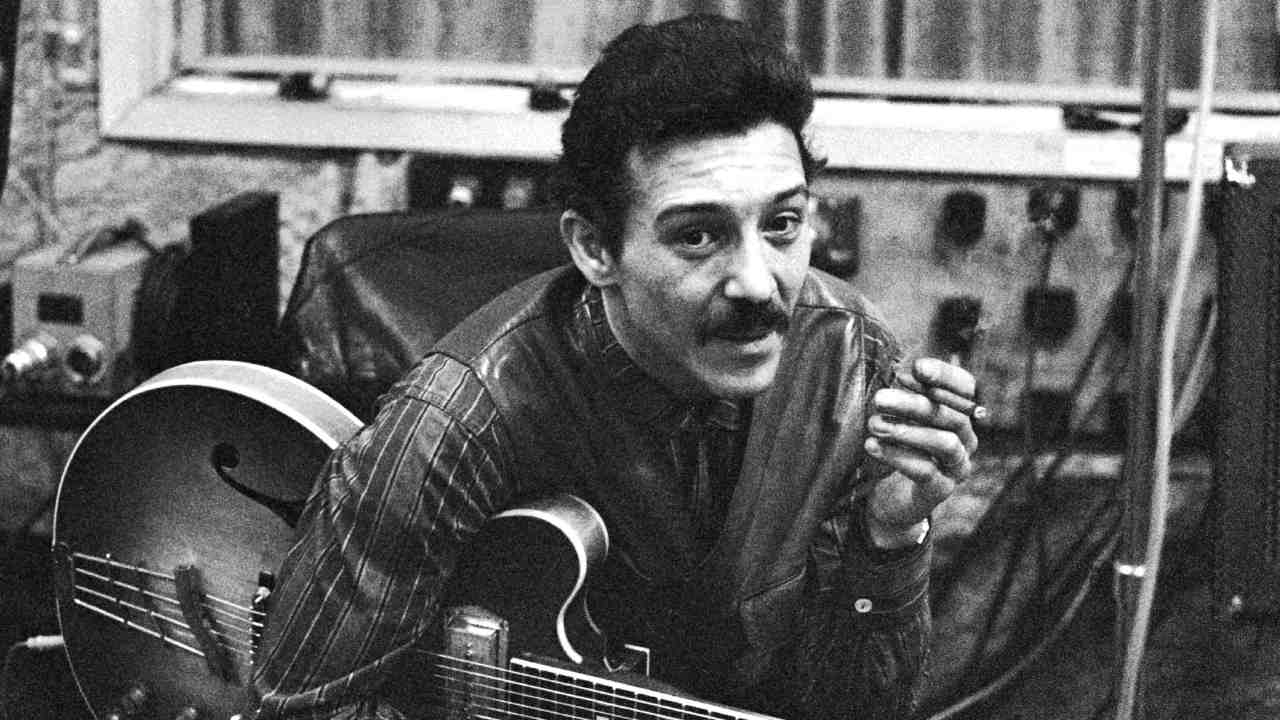

In the cold light of today, Alexis Korner looks an odd kind of character. There’s a famous black-and-white photo of him in a striped shirt and tightly knotted necktie, holding a smouldering cigarette.

He’s got a long, mournful, serious-looking face, a big mane of tousled black hair and huge furry sideburns. He looks like a villain out of a 1960s TV thriller; the nemesis to Patrick McGoohan in an episode of Danger Man, perhaps. Or maybe the blunt-talking anchorman on a late-night intellectual series about the arts.

Both descriptions, are wide of the mark. He was, and remains, the godfather of British blues. And yet, strangely, he’s not best remembered for his musical contributions to the genre. Rather, Korner’s main role was as a networker. A facilitator. A King Bee. He was the hub toward which a whole host of young talented British bluesmen were attracted.

Korner came from a odd background. He wasn’t born of the banks of the Mississippi, obviously, but neither did he come from a typically British upbringing. Korner was born in 1928 in Paris, the son of an Austrian father and a Greek mother. His full name signifies his heritage: Alexis Andrew Nicholas Koerner. He emigrated to England with his family at the start of World War Two, which is where he discovered his love for US blues.

“I used to nick 78rpm records from Shepherd’s Bush market,” Korner once recalled. “One of the first records that ever vanished into the saddlebags of my bicycle was Jimmy Yancey’s Slow & Easy Blues.”

“I used to nick 78rpm records from Shepherd’s Bush market.”

Alexis Korner

Korner used to listen to Yancey’s scratchy ol’ classic during German air raids. It provided a strange kind of comfort. “From then on,” he said, “all I wanted to do was play the blues.”

Post war, Korner established himself as an important figure in the burgeoning British blues movement. However, he influenced and helped develop the scene without ever really becoming a major player himself. Korner was a mover and a shaker; a fulcrum; a focus; a conduit. He released numerous albums during his lifetime – but it’s the musicians who played and sang on these records that people remember, more than Alexis himself. Look at the credits of these records and many of them read like a who’s who of the British music scene of the 60s and early 70s.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In 1954, Korner and Cyril Davies – Britain first Chicago-style blues harmonica player – opened their own blues club, The London Blues And Barrelhouse Club, in London’s Soho. They brought both famous and unknown American blues artists over to the capital to showcase their talents. When Muddy Waters came over to Britain in 1958, the only club he played in London was the one run by Korner and Davies.

Later, in the early 60s, the pair formed their own band, Blues Incorporated. Korner (guitar, vocals) and Davies (harmonica, vocals) were joined by Ken Scott (piano), Dick Heckstall-Smith (saxophone) and a revolving cast of musicians including Charlie Watts, later of The Rolling Stones, on drums and Jack Bruce, later of Cream, on bass. Guest vocalists included Art Wood (the older brother of future Faces/Stones guitarist) Ron Wood) and Long John Baldry. John Mayall was so impressed by Blues Incorporated, he used them as the blueprint for his own band, Bluesbreakers.

March 1962 saw Korner open a new, improved jazz club in Ealing, west London, which attracted the likes of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Ian Stewart, Steve Marriott, Paul Jones, Manfred Mann… in the audience and on stage. The list is practically endless. A British blues rockin’ scene was born.

He was a big influence on Brian Jones especially and even suggested that vocalist Paul Rodgers, guitarist Paul Kossoff, bassist Andy Fraser and drummer Simon Kirke adopt the name ‘Free’ for their new group. Korner also recommended that Island Records supremo Chris Blackwell should sign this up-and-coming blues combo. Blackwell duly obliged.

With all this talent surrounding him, the question must be asked: how come Korner himself didn’t go on to greater things? Well, he was, perhaps, too much of a purist; too scholarly – too professorial, perhaps – in his approach.

The fact that Korner was openly critical of America’s fixation with tripped-out psychedelic blues rock of the late 60s – think Blue Cheer, Iron Butterfly and of course The Grateful Dead – made him look like a crusty old colonel in some eyes. And yet, perversely, Korner also disliked the way many British musicians were content to play the blues at its most basic.

“If they are going to insist that blues is a 12-bar form with a specific harmonic sequence, with only about three variations, and that the basic lyrics are: ‘My baby done left me’ or ‘This is the name of the bird I made it with last night’, then they can’t expect the interest to last very long,” he once told Melody Maker

“In blues anyway, it is the content that is most important, not the form.”

Alexis Korner

“If they are going to stick so violently to the form, then the standard of content must get a lot higher. In blues anyway, it is the content that is most important, not the form.”

In the light of the above comments, it’s ironic that Korner enjoyed his biggest success in the 1970s as the leader of CCS, or Collective Consciousness Society. With CCS, Korner was able to indulge his love of jazz as well the blues. Put together by record producer/music impresario Mickie Most, CCS were a 25-member combo that specialised in big band treatment of rock’n’roll tunes.

Their version of Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love was adopted as the theme tune to Top Of The Pops and reached No.13 in the British singles chart in autumn 1970. Follow-ups Walking and Tap Turns On The Water faired even better, reaching Nos. 7 and 5 respectively. And yet, while Korner was grateful for the success CCS gave him, he always preferred intimate, smoky clubs to the big showcase concerts. It’s perhaps significant that Korner once even claimed that CCS actually stood for the Chigwell Co-operative Society.

After CCS, Korner formed Snape with ex-King Crimson musicians Boz Burrell (bass) and Ian Wallace (drums). Alexis’s smoky voice also enabled him to forge a career as a voiceover man for TV and radio advertising. Sadly that smoky voice was also to be his undoing: Korner died of lung cancer on January 1, 1984.

So, although Korner never really gained success as an individual, today he is recognised as being a hugely influential figure for numerous artists, from The Rolling Stones to Led Zeppelin. Legend has it that Jimmy Page first heard Plant jamming with Korner. Indeed Plant recorded two songs with the latter: Steal Away and Operator. As a result, Page invited Plant to join the New Yardbirds, which transformed into Led Zeppelin.

Terry Reid, who famously turned down Page’s offer to sing for Zeppelin, might tell it entirely differently, but that’s another story for another time. Whatever the truth, let’s give Alexis Korner his due as the man who ushered in a new generation of blues.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Cream The Story Of British Blues Rock

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.