"It's not telling a story, there’s no concept or anything." Mike Oldfield and the strange miracle of Tubular Bells

In 1972 a rejected demo finds its way into the hands of a young maverick label boss. The eventual result is a commercial and cultural phenomenon: Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

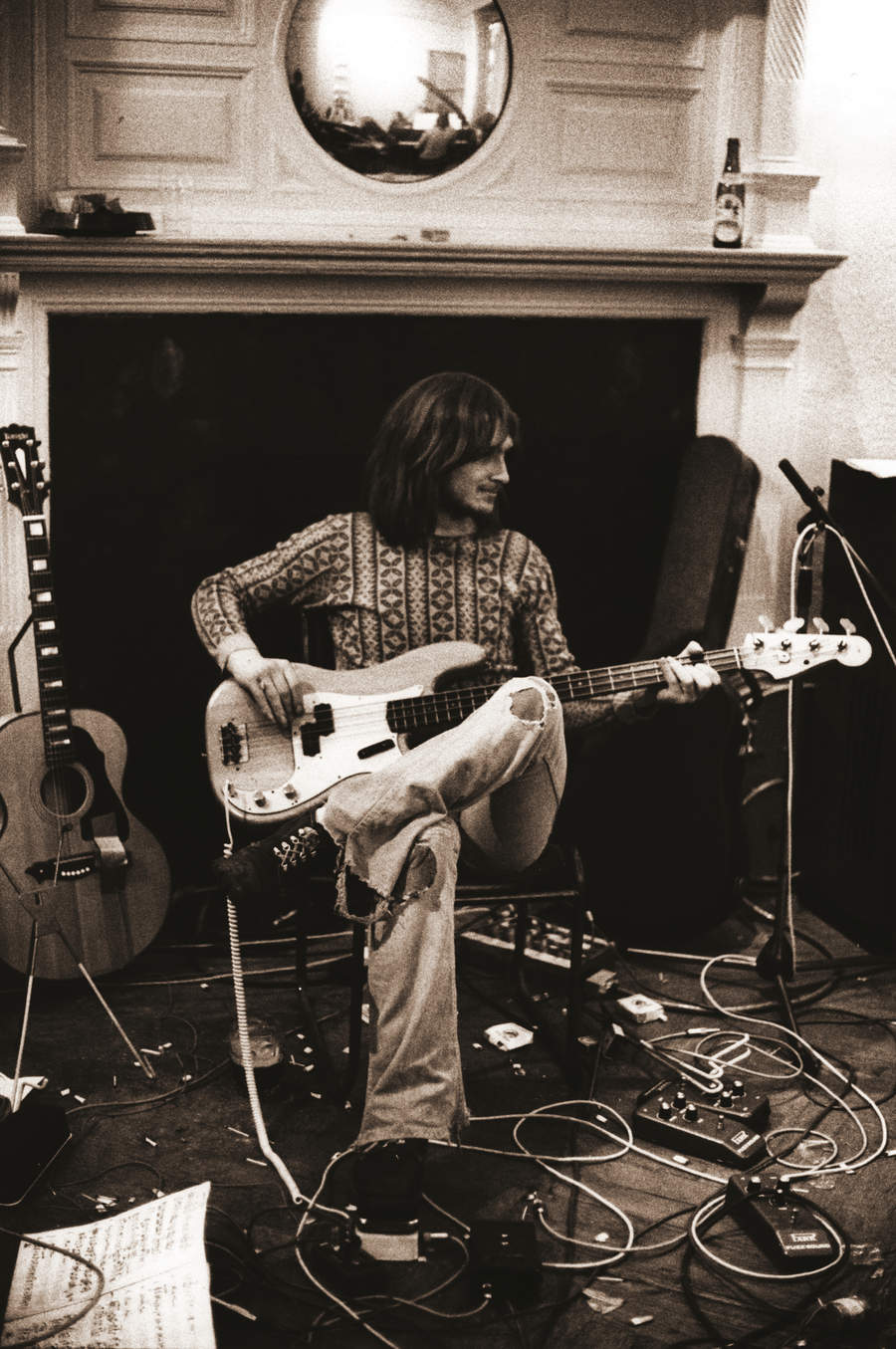

It’s Autumn 1972. John Cale is vacating The Manor, a picturesque residential studio nestled in the Oxfordshire hills. It’s a recent acquisition by a budding music impresario called Richard Branson. The next artist booked in the studio is a wan, taciturn 19-year-old virtually unknown called Mike Oldfield. Noticing a shining silver set of tubular bells among Cale’s equipment, Oldfield asks if he can add it to the two dozen instruments he’ll use to record his one-man symphony, tentatively titled Opus One.

Re-titled Tubular Bells and released the following year, after a slow start the almost all-instrumental album went on to become a commercial and cultural phenomenon, and launched Oldfield as one of the UK’s most acclaimed composers. The first album to be released on Branson’s fledgling Virgin Records, its massive worldwide sales bankrolled the label for years to come and set Branson on course to becoming the country’s most recognisable captain of industry.

Thirty six years later, in 2009, with his Virgin contract ended and the rights to the album now his again, Oldfield, the arch-tinkerer, remixed and reissued it. Surely it’s difficult for him to remain objective about a record he knows inside out?

“It’s actually easier now,” he said then. “Listening back, the sound quality is actually great, and the most amazing thing about it was that it was all first take. Nobody, myself included, would dream of doing that now. One of my first decisions about this remix was to leave it as played. There’s a spontaneity about it, a dynamic drive that would’ve been lost, so I left in the squeaks and pops and the few bad notes. They’re far overshadowed by the power and purpose of the playing.”

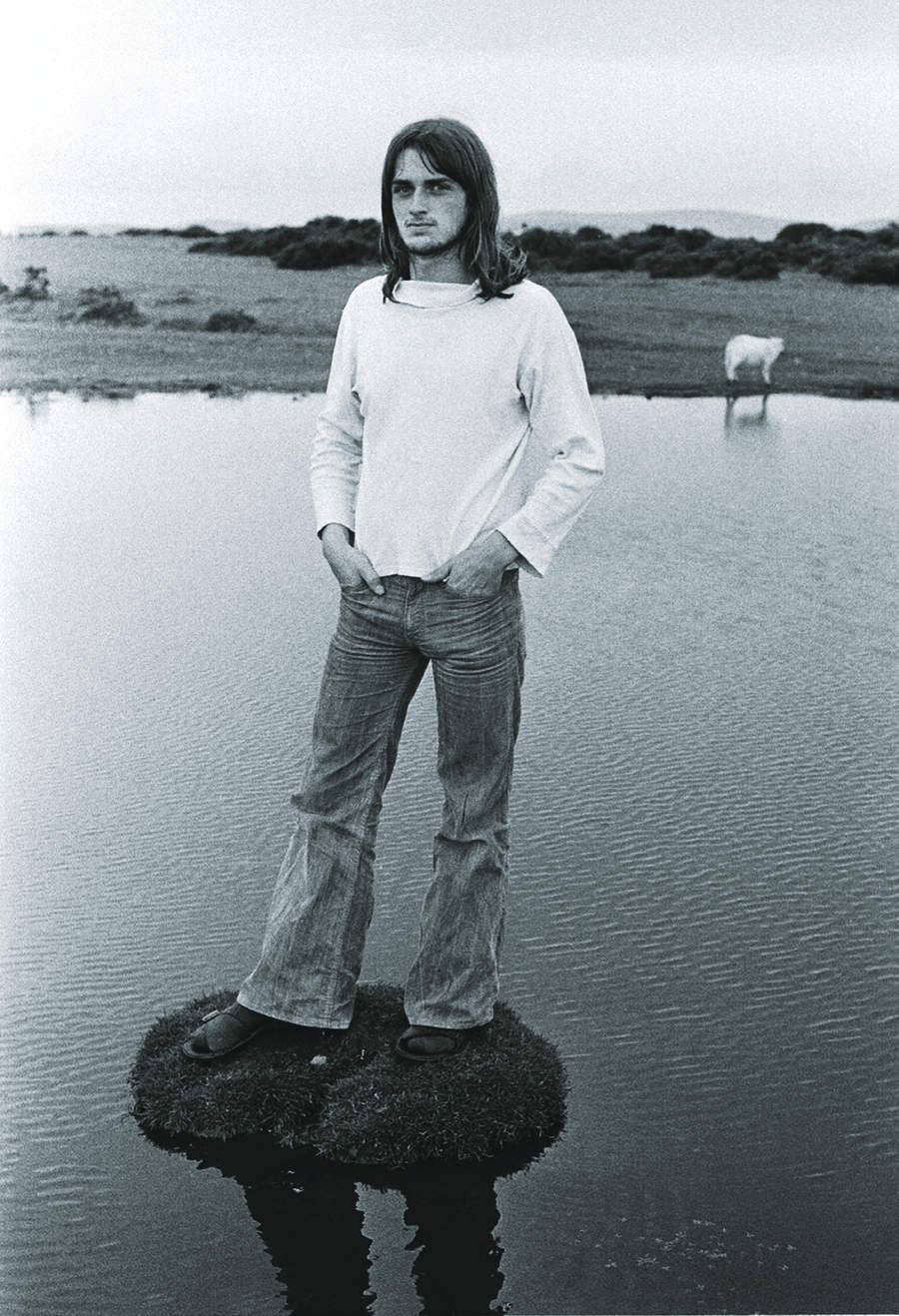

Back in the day, the music’s main purpose was to keep the troubled teenager on an even psychological keel. A loner since childhood, Oldfield suffered with a sense of otherness, amplified by his mother’s mental illness and alcoholism. He himself came to rely heavily on the bottle. And one extremely damaging LSD trip led to decades of crippling panic attacks.

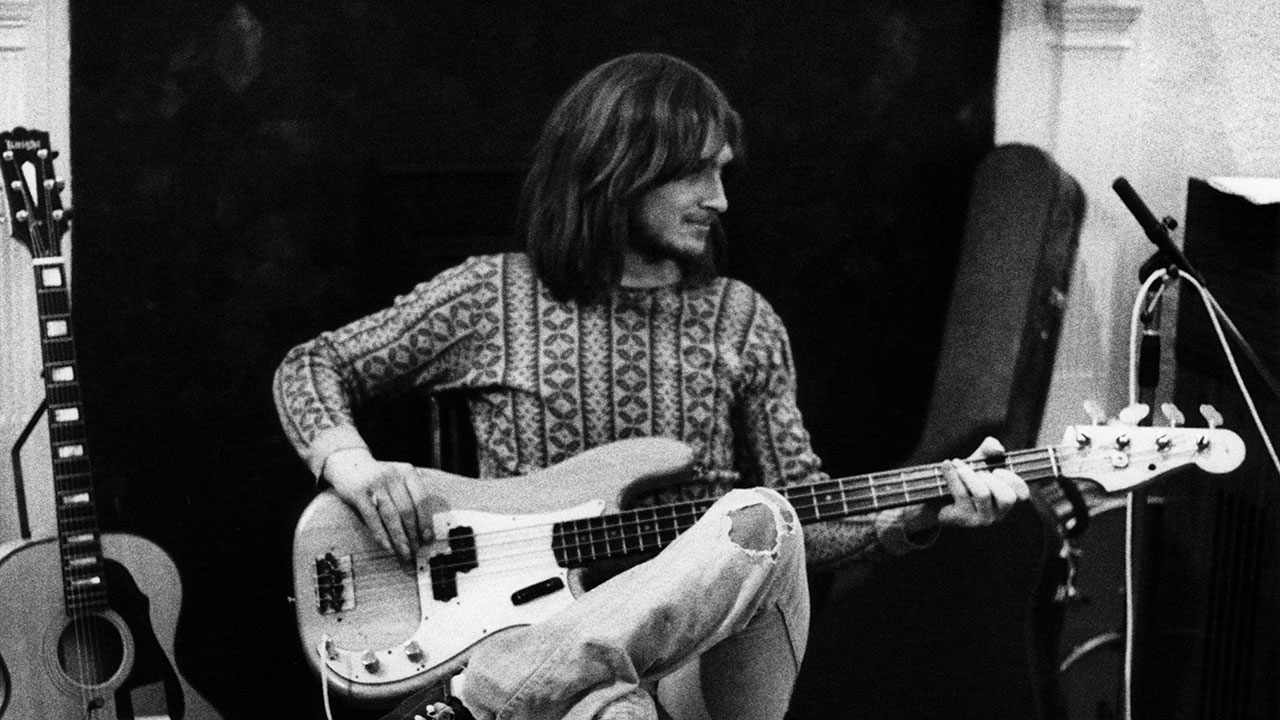

Mike Oldfield discovered his talent for music early on. He began his career on the 60s folk circuit in acts including The Sallyangie, a duo with his vocalist sister Sally, and later joined Kevin Ayers’ Whole World as bassist and guitarist. By then, rock’s horizons were expanding.

“In the late sixties, progressive music was what everybody wanted to make. There was experimentation all over the place; we were all pushing boundaries seeing what could be done," Oldfield explained. "I was very much part of the live music scene, going up and down the motorway, and we’d often be on the bill with groups like Pink Floyd, Free and even Black Sabbath. I never set out to absorb any influence, it was all just there.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Oldfield absorbed eclectic musical ideas, however; classical structures, minimalism, unusual scales and odd time signatures. Prior to Bells ringing his name around the world, a rough demo he recorded had been rejected by every record label he sent it to. But when he first set foot in The Manor in 1971, as bassist for Jamaican singer Arthur Louis, the studio’s resident engineers Simon Heyworth and Tom Newman heard promise in the youngster’s recording. They passed it on to Manor owner Richard Branson and his business partner Simon Draper.

A year later, he was invited to record the piece properly at The Manor for Branson’s new Virgin Records label. “It was a lovely big country house with a complete recording studio,” Oldfield recalls. “Lots of people running around doing things. We had a cook so I’d get great big plates of wonderful food, and I made lots of new friends.”

With instruments ranging from organs to mandolins to Cale’s tubular bells, Oldfield set about recording his Opus One, filling 16 tracks of tape with thousands of overdubs to achieve the sound in his head. Part One was finished in one manic week, with the voice of the ‘Master Of Ceremonies’ provided by Vivian Stanshall of the Bonzo Dog DooDah Band, who’d arrived at the studio early for their own recording sessions.

Part Two came together slowly during studio downtime over the coming months. For its creator, the whole process was cathartic. “You can hear it in the music. It was the only time I felt sane and vaguely happy. I suppose it describes in a nutshell the anguish of teenagerhood, which most people can relate to. It personifies all that.

“Nothing can take away from the fact that I’m very, very proud of the composition, the way one idea runs into another idea and the variations of ideas scattered around the place. It’s got a great introduction, great riffs, lovely little tunes. It’s fortuitous that Viv Stanshall was there at that time. And what a good idea to put the bell in there. It all seemed to fall into place, as if some wheel of fortune had swung in my favour at that time.”

Artist Trevor Key was commissioned to design its now iconic cover, and the album, re-titled Tubular Bells, was released on May 25, 1973. Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon had landed two months earlier, and with it the progressive era was in full flow.

Oldfield’s one-man symphony earned rave reviews in the press and won fervent support, notably from Radio 1’s John Peel. Tubular Bells entered the UK Top 10 and stayed in the chart for five years straight. Worldwide sales were spurred further when William Friedkin used the haunting opening section for the soundtrack of his horror film The Exorcist, which brought Oldfield a Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Composition in 1975.

Still plagued by the panic attacks and a morbid fear of flying, Oldfield refused to take the album on the road at home or in the States, despite Branson’s pleas. He did agree to doing one concert, though, at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, but only after Branson gave him his vintage Bentley as an incentive. Oldfield also prepared a tourable, orchestral version of the album.

“I didn’t like it too much,” he says. “It was Virgin’s idea because at the time I didn’t want to go on tour.”

Oldfield subsequently tempered his demons through Exegesis therapy (the root of which is based on the idea that one’s own problems are self-caused and not the fault of others), and his post-Tubular Bells career includes many other highs: another No.1 with ’74 follow-up Hergest Ridge; cracking ’75 album Ommadawn; his No.4 single Moonlight Shadow with Maggie Reilly in ’83; his underrated soundtrack to Roland Joffé’s harrowing film The Killing Fields; his acclaimed classical suite Music Of The Spheres in 2008.

Yet it’s Tubular Bells – and its franchise – for which he will forever be best known. After his original, contentious, contract with Virgin expired in ’92, Oldfield delivered Tubular Bells II for Warner Bros. It was a No.1 hit. Six years later the brand continued with Tubular Bells III, a top-five success. But it hasn’t all been success. “The re-recording rights for Tubular Bells came back to me in 2003, which encouraged me to re-record it, for its thirtieth anniversary. That was great fun to me, but nobody else seemed to like it. I’m scared to listen to that now in case I think it was a big mistake!”

That re-recording flopped, perhaps because the so-called flaws in the original had become part of its very fabric. Four years later, the Mail On Sunday did a deal with EMI/Virgin to give away a CD of the original Tubular Bells free with the newspaper. Hardly surprising, Oldfield was furious at the time. “It devalued it in a way. It was like saying, this music’s so old that we’ll just give it away. On the other hand, it marked the end of that era and gave me the impetus to really want to remix it.”

That opportunity arose when the album’s absolute rights devolved to him in 2008. In the new mix the squeaks, pops and duff notes may have survived, but there was been one high-profile casualty. “The original bell had some distortion on it, which was impossible to get rid of. In the mid-seventies I was convinced to replace the bell with one that didn’t have distortion, and I foolishly agreed, and we rubbed it off.

"We haven’t been able to track down the original multitrack master – I’ve been working from a copy. I was pulling out my hair thinking: ‘What can I do?’ In the middle of Part One there’s a simple flute tune and in the background is the same bell. It was playing some of the right notes, so I spent days reproducing exactly the original bell using that, and with some jiggery-pokery I think it’s even better than the first one now, and it hasn’t got the distortion.”

Yet he was also mindful of keeping the mix in balance with the classic version. “The beginning has a spooky feel that reminds you of things like The Exorcist, and if you clean it up too much then it doesn’t have that. I didn’t duplicate some of the production, the phasing and flanging; we were trying to be modern in 1973, now it didn’t seem necessary. I hope I’ve done it as best as I could, I certainly enjoyed doing it.”

With decades of perspective, its creator has definite view on the reasons for Tubular Bells’ enduring success. But just be careful what you call it. “I’ve got no patience for people who call it new age or who go on about it being a concept album. It’s not telling a story, there’s no concept of anything. What it does have is extremes – delicate mandolin sections, the pounding rock of the ‘caveman’ section, the next section is the dreamiest little piece.

Also I think people miss the humour in it. There’s a honky-tonk piano with drunken people humming along, the Sailor’s Hornpipe, it’s got that Monty Python silliness. There’s been nothing like it, before or since.”

Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells 50th Anniversary Tour Celebration continues until March 31.

A music journalist for over 20 years, Grant writes regularly for titles including Prog, Classic Rock and Total Guitar, and his CV also includes stints as a radio producer/presenter and podcast host. His first book, 'Big Big Train - Between The Lines', is out now through Kingmaker Publishing.