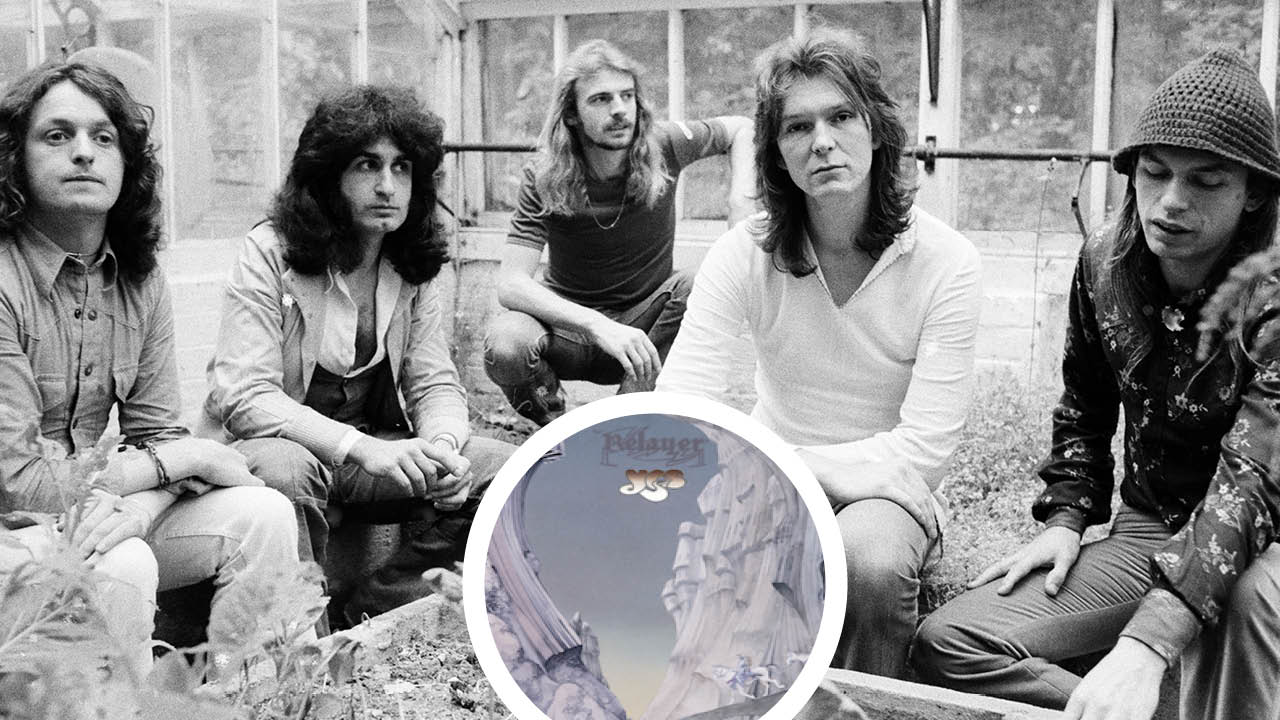

“Keith Emerson said, ‘Why do I need to join Yes when I have ELP?’”: the story behind Yes’ delirious Relayer album

Rick Wakeman was out, new boy Patrick Moraz was in, and Yes were about to make their most underrated album of the 70s

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It’s 1973 and Yes singer Jon Anderson is at home listening to a couple of albums he’s just been given. Always keen to catch up with was going on in the world of contemporary music, he turns his attention to Sing Me A Song Of Songmy by Turkish American composer Ilhan Mimaroglu. Released in 1971 it’s an eclectic soup of electronic sounds, avant-garde orchestral scoring, and trumpeter Freddie Hubbard’s jazz quintet interspersed with sung and spoken words addressing subjects that included actress Sharon Tate’s murder, the National Guard’s shooting of unarmed students at Kent State University and the war in Vietnam.

The other record is Vangelis Papathanassiou’s just released soundtrack album, L’Apocalypse des Animaux. Recorded in 1970 while the Greek keyboard maestro was still a member of Aphrodite’s Child, the exotically textured music hovers serenely, suffused with glistening, pristine beauty but laced with a gnawing melancholy. Occupying a wholly different sonic universe to the previous disc, the reflective nature of the bittersweet melodies captivates Anderson and whets his creative appetite.

As he listens, things are going well for Yes. Advance orders for their next release, Tales From Topographic Oceans have already ensured the double album will achieve gold disc status before it even hits the shops. A largely sold-out UK tour is about to start and advance sales for the American leg of the tour have pushed the band into even bigger venues than on their previous visit. With ideas and conceptual themes already beginning to emerge for the next project for the band to tackle in Anderson’s mind, the future for Yes looked very bright indeed. All things considered, what could possibly go wrong? Just seven months later he would find out.

Article continues below

Not everyone shared his mood. Profoundly bored having toured Europe and America with what he saw as a series of musical ideas spread too thinly across an over-inflated concept, Rick Wakeman had been unhappy for some time. Nor could he work up much enthusiasm for what he regarded as the jazz-rock-influenced direction Yes seemed to be heading toward next. On May 18, his 25th birthday and the day he received the news that his second solo album Journey To The Centre Of The Earth was at the No.1 spot of the UK album charts, Wakeman quit.

“Morale was low and obviously people were disappointed he’d gone because Rick was an important part of the band,” drummer Alan White recalled, speaking to Classic Rock in 2012. “I think we’d started working on some of the Relayer material before Rick left, but he had a bad taste in his mouth after playing and touring Tales From Topographic Oceans, and I guess he just wanted to carry on with his own music. We all got a grip and obviously started looking for a new person and started working as a four-piece to get the flow going. We spent a long time rehearsing getting the basic ideas for Relayer together.”

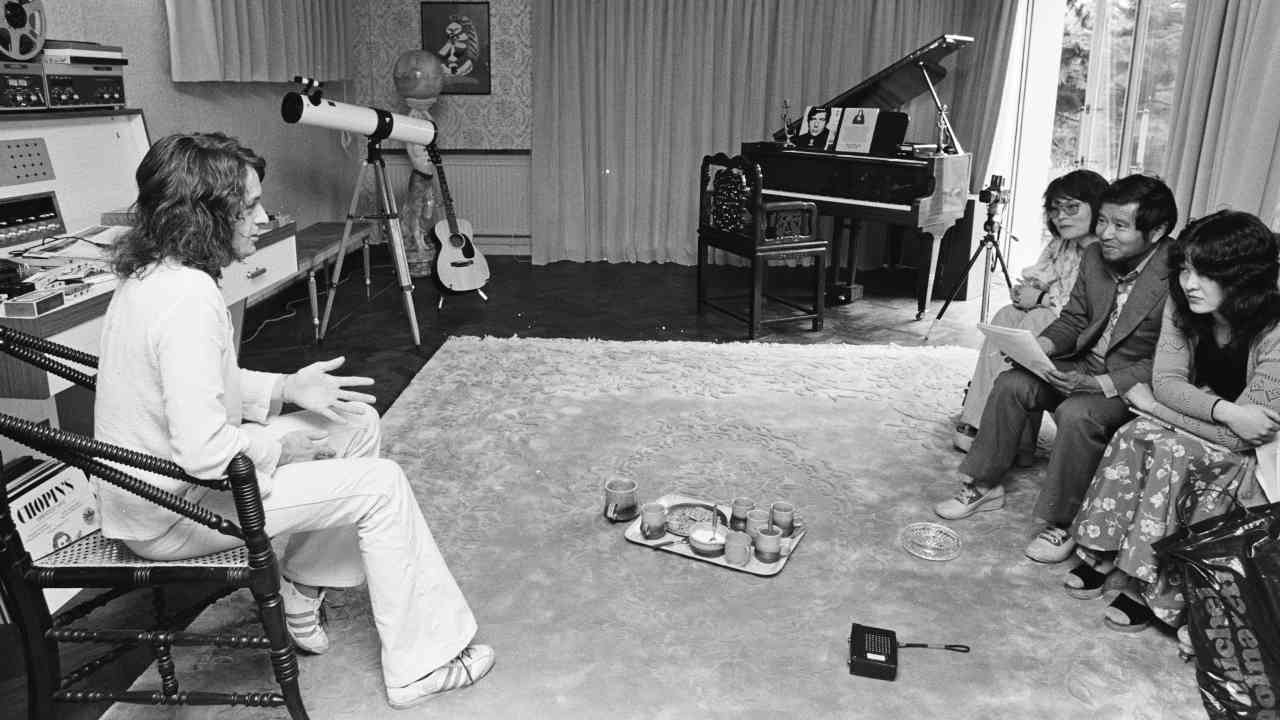

Recalling the strange, exotic timbre of L’Apocalypse des Animaux, Jon Anderson had an idea for a ready-made replacement for Wakeman. He put in the call to bring Vangelis over to the rehearsals underway at bassist Chris Squire’s house. The Greek’s ability to knit elaborate orchestrations and arrangements combined with his formidable abilities as a soloist should have made him a natural fit for the group. However, as the sessions got underway, it increasingly became clear that things weren’t proceeding as anticipated or desired.

“When we said let’s play that again, he’d say, ‘Well it won’t be the same,’” recalls guitarist Steve Howe. “We were kind of improvising but we were learning parts as we went along and I think that’s when we realised he was such a spontaneous player that Yes was going to be a problem for him. We were about working out a solid arrangement and relying on him at any given point to play something that we’d recognise. Vangelis felt he didn’t really need to. He was always going to play off the cuff which would have been wonderful, but we’re not a jazz group.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

After agreeing that there was little point in going on, Vangelis returned to London leaving the quartet to work on the new material. The guitarist remembers telephoning ELP’s Keith Emerson, whose arrival in the ranks of the band, had he taken up Howe’s invitation, might well have changed the course of progressive rock at the time.

“He said ‘Why do I need to join Yes when I’ve got ELP?’ Musically it would have been amazing to work with Keith Emerson but whether or not the personalities would have blended, I just don’t know. We were starting to realise that the personalities in the group is a very important thing and it doesn’t matter how much the music seems to be the goal, it won’t work unless you all get on.”

What they needed was somebody with a near-encyclopedic knowledge of Yes’ detailed arrangements and the technical ability to not only pull it all together but to throw in a few dazzling solos. The person who fitted that bill precisely was Patrick Moraz. The Swiss keyboard player was best known in the UK for his ebullient performances as a member of Refugee, the trio formed by Emerson’s former bandmates in The NIce Lee Jackson and Brian Davison after the keyboard player had quit to form ELP.

Refugee had bagged a deal with Charisma Records and they had been well-received on tour, but they were existing virtually hand-to-mouth basis. Moraz himself was living in a damp, rat-infested basement in London’s Earls Court, and it was common practice to have to walk three miles to the Refugee rehearsal room. He loved the music the trio were making, but when an invite came through to attend an audition with Yes, Moraz seized the opportunity and immediately encountered the very different world the musicians of Yes lived in.

Arriving early, he had an opportunity to watch the arrival of each member one after the other in their expensive cars. ““I was talking with the road crew who were looking after the place and as I looked out across the field I saw Alan White in his sports car - it was a special customised thing,” recalls Moraz. “Then Steve arrived in his metallic blue Alvin sports car, driven by his roadie. Then Jon came in an old-fashioned and rare Bentley, and then Chris arrived in what I think was a Rolls Royce Silver Cloud.”

As someone used to have to pay by the hour for a rehearsal room, Moraz was struck by the leisurely pace as people sat back chatting, smoking, and drank tea. “I tuned the instruments before we started playing together and that gave me an opportunity to play around those keyboards that Vangelis had used while the guys were getting ready. I was improvising, showing a bit of my speed and ability, and they stopped talking and all gathered around the electric piano and the Moog to watch and listen. I played all sorts of things, including a little bit of And You And I. To be honest, I think I got the gig at that point before we’d even played a note together.”

The band played him the vocal section of Sound Chaser. Moraz was staggered. “They played it at an unbelievable speed,” he recalls. “Then Jon asked me what I’d offer as an introduction to the piece.”

In an instant the electric piano arpeggio that opens the piece tumbled from his fingertips immediately capturing the band’s attention, asking him to explain what he’d just played with a view to integrating it into the piece.

“I explained the rhythm to Alan and Chris so they could work out the answer to the keyboard’s call as it were. I even suggested to Jon that he use his flute to which I could play these little fast clusters.” As the tape rolled they did a few takes, slowly at first but then accelerating as the parts became more familiar. “Then we recorded the introduction in a take that was used on the finished album before I was offered the job.”

Alan White was buzzing with excitement at the new additions to the track. “The first time Patrick played with us he had this jazzy prog kind of intro that became the opening of Sound Chaser. It didn’t really have a fixed time to it but rather it was something that was felt between the keyboards and drums. I come in with the drum pattern that’s in 5s and 7s. I got to know the lick real well and played it note for note on the drums around the kit.”

For his part, Steve Howe remembers a feeling that the band was once again whole with the recent uncertainty and frustration they’d experienced now behind them. “Once we had Patrick in there we were up and running. . .his flamboyance brought something like fresh blood to the thing like I had when I joined and like when Rick joined. Patrick was more than capable of holding the fort.”

Anderson’s musical concepts for The Gates Of Delirium took all of his considerable powers of persuasion to convince the rest of the band that the piece was viable. “My main focus at that time was to have a complete idea before I showed it to the band,” says Anderson. “I played most of it on piano and it must have sounded very strange and not too musical to the guys, as I didn’t play that well at that time. But I seemed to know each section, and why it could work as a whole. So I was very happy when they decided to take it on.”

There was always an element of cajoling and exhorting the others to follow a musical line of inquiry suggests Anderson. “The ideas would come to me very fast, and structure was something that I was learning about at the time. So I’d always be one step ahead of the guys while they were learning the last part, and I’d be onto the next part, sort of leading the way; this is where we’re going, this is how we’re going to do it, and give it a shot. Maybe it’ll work, it might not, but let’s give it shot. Recording the battle scene was a bit chaotic at the time.”

Alan White remembered that chaos with some fondness. “It extended to Jon and myself going to a scrap yard and banging pieces of metal in the morning for about an hour to see what sounded good. We actually built a frame in the studio made out of springs and car parts which of course ended up on the album in the battle section. It was pretty crazy stuff.”

Though much is made about the ambiguous nature of Anderson’s lyrics, the words to The Gates Of Delirium are arguably amongst his most straightforward, albeit presented in his unusual, idiosyncratic syntax. Just as the architecture of Sibelius’ third symphony had influenced the structure of Close To The Edge and the writings of Indian mystic Paramahansa Yogananda, introduced to him by King Crimson percussionist, Jamie Muir after they’d met at Bill Bruford’s wedding reception, had helped Anderson with the conceptual framing of Tales From Topographic Oceans, Tolstoy’s War And Peace, and perhaps elements of Ilhan Mimaroglu’s sound collages could be said to have fed into Anderson’s ideas for a suite dealing with the psychology of power and ideology left unchecked.

“It was still a very sad time with Vietnam lingering in my mind and the Cold War. There seemed no end to the cycle of warmongering around the world,” says the singer.

It’s also worth noting that on the finished album, after the storm of battle, there’s a moment of calm as the mists and smoke begins to clear, the music has echoes that Anderson first heard on Vangelis’ L’Apocalypse des Animaux. It’s surely no accident that Création du monde from that album was played pre-show during the subsequent Relayer tour.

Despite the ambitious and sometimes difficult musical terrain it mapped out, upon its release in the winter of 1974 it was in the top 5 of the album charts on both sides of the Atlantic. Housed in the final Roger Dean cover of the 1970s, it also included some of their most angular music to date.

Yet away from all the rhythmic turbulence and jazz-rock dissonance, the album’s closing track, To Be Over radiates an emotional yearning that gives voice to Yes’s gentler inclinations without compromising the kind of intensity they would fully explore later with Awaken. From their debut up to Tales From Topographic Oceans, the band’s collective capacity to assimilate and harness differing ideas and influences appears measured and incremental, each one building upon the successes and lessons learned from its predecessors yet in this context Relayer feels the most radical of them all and in the ensuing years its reputation and the esteem in which it is held has continued to grow.

Speaking in 2012, Alan White rated the album as one of his favourites. “We were all totally into it. We were in the studio and coming up with new ideas on a daily basis. An album doesn’t sound good unless you’re having fun and that’s what you hear when you put that record on: Yes having fun.”

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.