The Tom Waits' albums you should definitely own

From boozy beat poet to avant garde conductor of the 'Junkyard Orchestra', a guide to Tom Waits' best albums and the work of a musical maverick

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Born in the back of a cab in the parking lot of Pomona hospital in California, Tom Waits has confounded expectations since he emerged from the womb in December 1947 – no doubt sporting a goatee and battered pork-pie hat even then.

Waits is an old-school Californian and ageless shaman. He cut his teeth playing piano and accordion in the strip clubs and burlesque academies of San Diego, San Francisco and Los Angeles, sharing boards with beat poets, satirists and the social misfits who informed his early songs. An underground cult hero, he was spotted at a talent night in the Troubadour Club by artist manager Herb Cohen, who added him to his roster of Asylum acts where he became something of a ‘project’ – meaning his low-key sales were offset by his evident charisma.

Waits’s career falls, or rather lurches, into three distinct categories. Early on he is a troubadour incarnate – not a singer-songwriter, although his songs were covered by Tim Buckley (Martha), the Eagles (Ol’ 55’) and Bruce Springsteen (Jersey Girl) – living in the Tropicana motel with a rented upright piano, an endless supply of rye whisky and no visible income. “I’m so broke I can’t even pay attention,” he quipped.

Having been dropped by Warner Bros, who wouldn’t release his Swordfishtrombones album, he pitched up at Island Records and phase two begins, characterised by an increasingly barking rasp, exotic arrangements and a theatrical style inspired by a series of soundtracks and film roles – The Outsiders, Rumblefish, Cotton Club, Ironweed – and his wife/muse, Irish playwright Kathleen Brennan. She has fired her husband through lean times, dark depressions and the whole artistic package.

By the end of the 90s Waits had achieved the goals of integrity married to financial independence, thanks in part to an unlikely cover of Downtown Train by Rod Stewart, which went Top 10 in America and Europe, and mostly to an effective lawsuit against the Frito-Lay crisps company who used a jokey Tom Waits soundalike for a Doritos commercial. An LA jury awarded Waits $2.45 million damages, prompting him to remark: “Now I have what I always felt I had... a distinctive voice.”

Phase three for Waits has been a marriage of the hard-boiled narrative and the simply hard-to-fathom. Increasingly ‘out there’, his maverick music embodies the phrase ‘tough love’. Those who know his ways are game for the perplexing twists. Curious newcomers are advised to dip in slowly.

Four albums in, Waits ups his ante. Note the punning title, because opening track Tom Traubert’s Blues (Four Sheets To The Wind In Copenhagen) marks a real shift in balladry, taking the Waltzing Matilda tune as a skeletal framework for an ambitious cantata. Rod Stewart covered this.

Elsewhere the sultry Pasties And A G-String (At The Two O’Clock Club) and I Can’t Wait To Get Off Work (And See My Baby On Montgomery Avenue) are gorgeous elegies to a dead-beat lifestyle. Jazzer Shelly Manne’s drums and Jerry Yester’s strings wrap it all up. Probably Waits’s most influential album, and a justly revered treasure trove of great songs expertly executed.

His final album of his ‘approachable’ era, self-produced and savvy, this conceptual suite opens with the staccato brainstorm of Singapore and the deadly stark Clap Hands. Quite an intro. Keith Richards plays lead guitar on Big Black Mariah, while the Uptown Horns’ juddering brass is smeared over crowd pleasers like Walking Spanish and a slew of film-noir vignettes that throw shade across Waits’ cinematic drift through urban midtown worlds.

The album also includes Downtown Train – a big hit for Rod Stewart five years later in 1990. That song and the album’s enduring quality have made this Waits’s biggest seller to date.

Heartattack And Vine (Elektra, 1980)

Despite the brilliance of predecessor Blue Valentine, this album has longer legs. Sidelined to Elektra Records as Warners’ love affair with their artist drew to a close, Waits spent a month in Hollywood making a pretty full-on and straightforward rock record; one where he took on electric guitar roles with Roland Bautista, and employed top session men, augmented by Ronnie Barron’s prevalent Hammond organ.

The result is a consistently listenable artefact studded with gems such as Ruby’s Arms and Jersey Girl. Pouting camp and clean shaven on the cover, this is Waits saying to his label: “Drop me if you dare.” They did.

Swordfishtrombones (Island, 1983)

Following his Oscar-nominated soundtrack for Francis Ford Coppola’s One From The Heart, Waits found his star rising in Europe thanks to the first of a trilogy of records based on Frank’s Wild Years about a used-furniture salesman who goes nuts and torches his house.

Character-packed, the album focuses on men back from war and hovering on the brink of terminal despondency. Littered with death and X-rated destruction, the whole piece is leavened with black humour in lyrical masterpieces like In The Neighbourhood and 16 Shells From A Thirty-ought Six. If Bob Dylan had turned his gaze on America post-Nam he couldn’t have bettered this.

The Black Rider (Island, 1993)

On a par with the preceding Bone Machine, the money shot comes here as Waits teams up with New York theatre dude Robert Wilson (later embraced by Talking Heads’ David Byrne), and legendary drug author William Burroughs whose cut-up novel technique provided the well from which the songs were drawn.

Recording in Hamburg with Californian sidemen and German orchestration, Waits finds hot discipline in a cold shed. Far from sounding like spontaneous chaos, the album has unexpected oases of calm. The folky love songs The Briar And The Rose and I’ll Shoot The Moon are just as startling as hearing the ancient Burroughs on T’Aint No Sin.

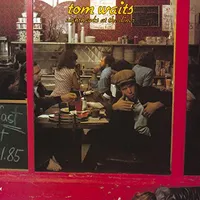

Nighthawks At The Diner (Asylum, 1975)

This double quasi-live album – recorded ‘live’ in a studio with an audience of guests and a free bar – includes staple old favourites wrapped in a blue- collar comfort blanket before the sturm und drang of later years. This is his milieu of ‘bad livers and broken hearts’, rather than the ‘demented parade band’ sound of a decade later.

Working with a quartet, Waits pays some dues and doffs his jockey’s cap to the likes of Dr John, Stan Getz and various country truck-stop gals in an embracing set. Just to show he was walking it like he talked it, he even had ‘Nighthawk’ tattooed onto his right arm. Here’s Waits aged 27; a lean, mean singing machine.

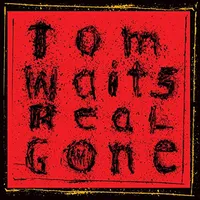

Does what it says on the tin. Only more so. This record locates Waits’ ‘cubist funk’ – a weird mash-up of Jamaican rock-steady, African, Latin and James Brown grooves. Waits wrote the songs a capella-style and refused to use his trusty piano. It’s a long journey from Ol’ 55.

You’ll need a strong stomach for what ensues: a gut- wrenching mélange of noise with manic turntable mixes of incessant mouth rhythms, dug up from the grave field recordings and blasts of hip- hop. It’s a right ruddy racket that sounds like the Rolling Stones bled through a West African blender by someone with a grievance against humanity. You can’t dance to it.

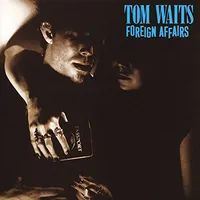

Foreign Affairs (Elektra, 1977)

Not everyone’s Waits favourite, usually because of the duet with Bette Midler on I Never Talk To Strangers (though this fuelled his belief in soundtracking One From The Heart). It’s probably Waits’ most polished AOR outing – he sounds like he’s under heavy manners to, er, sing nicely – despite ‘live in the studio’ protestations on the sleeve.

There’s a decent mix of beat references in Jack & Neal/California, Here I Come, a Western waiting to happen in Burma Shave, and an epic slice of cautionary humour in the poetic title track. Those who recall his one-time fling with Rickie Lee Jones will nod at the reference ‘Chuck E Weiss is back in town.’ Schmoove.

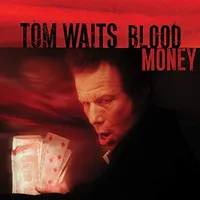

One of his most complete collaborations with wife Kathleen as lyrical editor (“she’s the brains behind Pa”) Blood Money is loosely based on a German play called Woyzeck, a tale of cuckoldry and horrible revenge. Right up Tom’s strasse. Melodically challenging but intricately ornate – ‘We all like bad news out of a pretty mouth’ – it has all the Brechtian and vaudeville references one expects from Waits, wrapped up in marimbas, bass clarinets and extravagant harmonica blowing, with a supporting cast of top Danish session men.

Much delayed, perhaps because Waits was so prolific he was in flood, the album’s artwork was overseen by Bob’s son Jesse Dylan.

...and one to avoid

You can trust Louder

This would not be a good introduction to Tom Waits. A double live album of varied quality recorded in Europe and the US, some of the tunes (Big Black Mariah) smack of super-sessioneering while others (Train Song) are over-embellished. There are purple patches like Yesterday Is Here and Way Down In The Hole, which sound like scripts for a Coen Brothers movie.

Oddly, the highlight is a studio recording, Falling Down, done with various members of Little Feat. Neither a contract filler nor a marking-time episode Big Time is one for the old-time purist. It was originally released with a (now) super-rare video. In typical Waits fashion the album and the visuals barely match.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.