Kettles and bacon: the tortured creation of Pink Floyd's Atom Heart Mother

Looking back at the making of one Pink Floyd's most overlooked but important releases, Atom Heart Mother

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

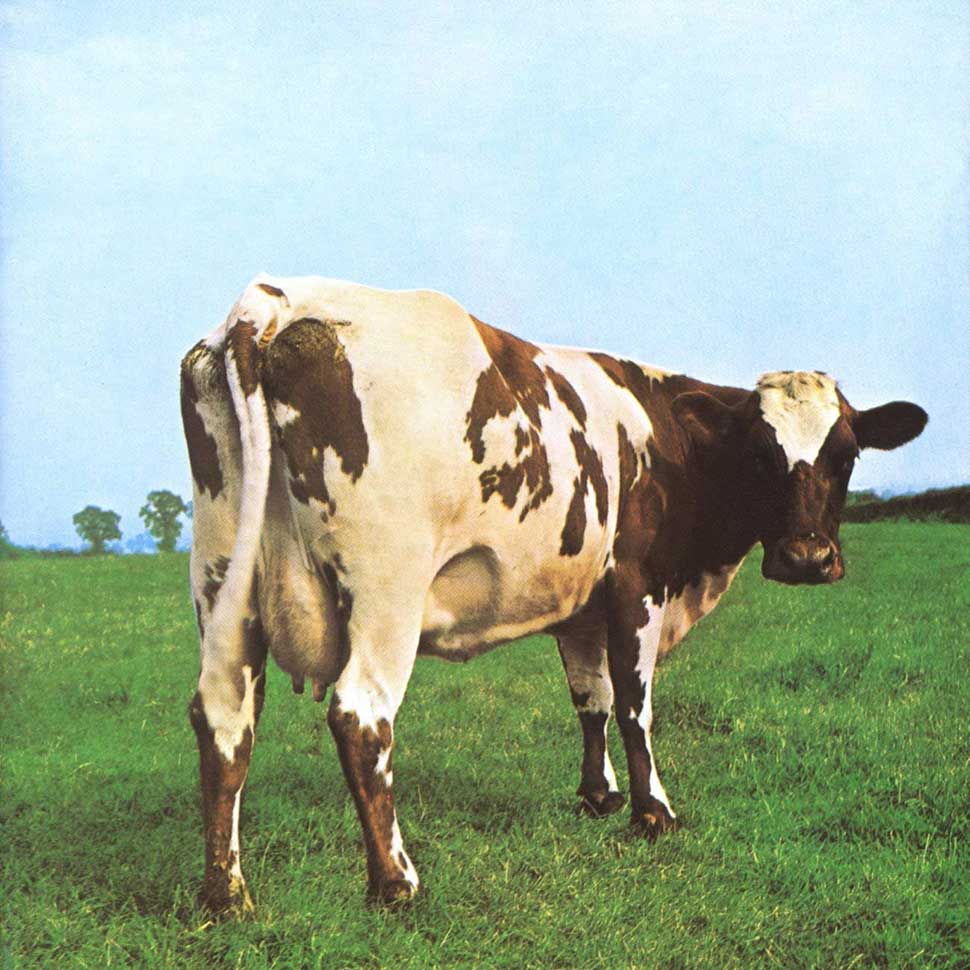

It was summer 1970, and LG Wood, managing director of EMI’s Record Division, was peering at the cover of Pink Floyd’s new album, Atom Heart Mother. It was EMI policy for Wood to sign off on all EMI album sleeves, but here was a cover without a title and the group’s name. Instead it was just a cow in a field. Presuming there were words somewhere, Wood turned the sleeve over, only to find more cows. According to one eyewitness, “Ah, Friesians” was all the baffled MD could muster.

Three months later, Atom Heart Mother became Pink Floyd’s first No.1 album. EMI’s powers that be already knew that strange-sounding hairy rock groups sold lots of records. Now, it seemed, they could do so without including their name or the album title on the cover. Just a cow. In a field.

Pink Floyd’s gargantuan seven-volume box set, The Early Years 1965-1972, released in 2016, might have dedicated an entire volume, Devi/Ation, to Atom Heart Mother and the Zabriskie Point soundtrack that inspired its title track, and included the earliest known recording of the AHM suite. But today, Atom Heart Mother is probably better known for the cow than the music.

Revisiting the album now is like entering a parallel universe inhabited by epic orchestral suites and songs created from the sounds of boiling kettles and frying bacon.

Pink Floyd would make better albums, but Atom Heart Mother remains the apotheosis of their experimental era – or as guitarist David Gilmour later described it, “our weird shit”.

An album that ended with a cow in a field in Potters Bar, Hertfordshire began more than a year before in Rome. Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni had commissioned Pink Floyd to score his next film, Zabriskie Point. They arrived in Rome to start recording in November ’69.

Antonioni’s 1966 movie Blow-Up had been a clumsy portrayal of Swinging London, and Zabriskie Point was a drama about US student radicals fighting ‘the man’, blowing stuff up and having lots of sex.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The early Pink Floyd embraced the unexpected and the concept of being, as drummer Nick Mason put it, “more than just a pop group”. They’d stopped releasing singles after December 1968 and had followed their second album, that year’s A Saucerful Of Secrets, with a soundtrack for the art house movie More.

Floyd’s next release, 1969’s half-studio/halflive double album Ummagumma, included Roger Waters’ musique concrète experiment, Several Species Of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together In A Cave And Grooving With A Pict. The piece was fashioned out of found sounds, with its composer ranting in a Scottish accent.

Zabriskie Point was the next stage on Floyd’s varied musical journey, but the band quickly discovered that Antonioni was an impossible taskmaster. “We did some great stuff,” insisted Waters. However, the director, worried that their music would overpower his film, criticised everything: “You’d change whatever was wrong and he’d still be unhappy. It was hell.”

Floyd lasted two weeks in Rome and then came home. Zabriskie Point was released in February 1970 and was a resounding flop. The soundtrack included just three Floyd tracks, padded out with songs by the Grateful Dead, among others. However, Floyd’s discarded out-takes contained a musical sequence around which the Atom Heart Mother suite would evolve.

“Dave [Gilmour] came up with the original riff,” Waters told Capital Radio DJ Nicky Horne. “We all listened to it and thought, ‘Oh, that’s quite nice…’ But we all thought the same thing, which was that it sounds like a theme from some awful western.”

It’s believed Pink Floyd performed the first version of their new instrumental on January 17, 1970 at the Lawns Centre in Hull. But they were still undecided on their next recording project.

“We’re going to do the music for an Alan Aldridge TV cartoon series called Rollo,” Waters announced in Melody Maker. “It’s rather Yellow Submarine-ish, about a little boy in space.”

But Waters never mentioned Rollo again. Instead, Pink Floyd entered EMI’s Abbey Road studios in early March to begin recording their new work. EMI had just installed state-of-the-art eight-track recorders that used a specific one-inch tape. The company insisted this tape was not to be spliced and used for edits, which meant Waters and Mason had the unenviable task of recording the backing track for their new composition in one 23.44-minute take. “It demanded the full range of our limited musicianship,” Mason said in his memoir, Inside Out.

There are moments on Atom Heart Mother when you get a taste of what Pink Floyd would soon achieve on Meddle and The Dark Side Of The Moon.

Pink Floyd had been playing the piece live for some weeks by now, tweaking the arrangement. “We added, subtracted and multiplied the elements,” said Mason. “But it still seemed to lack an essential something.”

The band eventually decided that the missing ‘something’ was an orchestra and a choir. But first they needed someone to write a score.

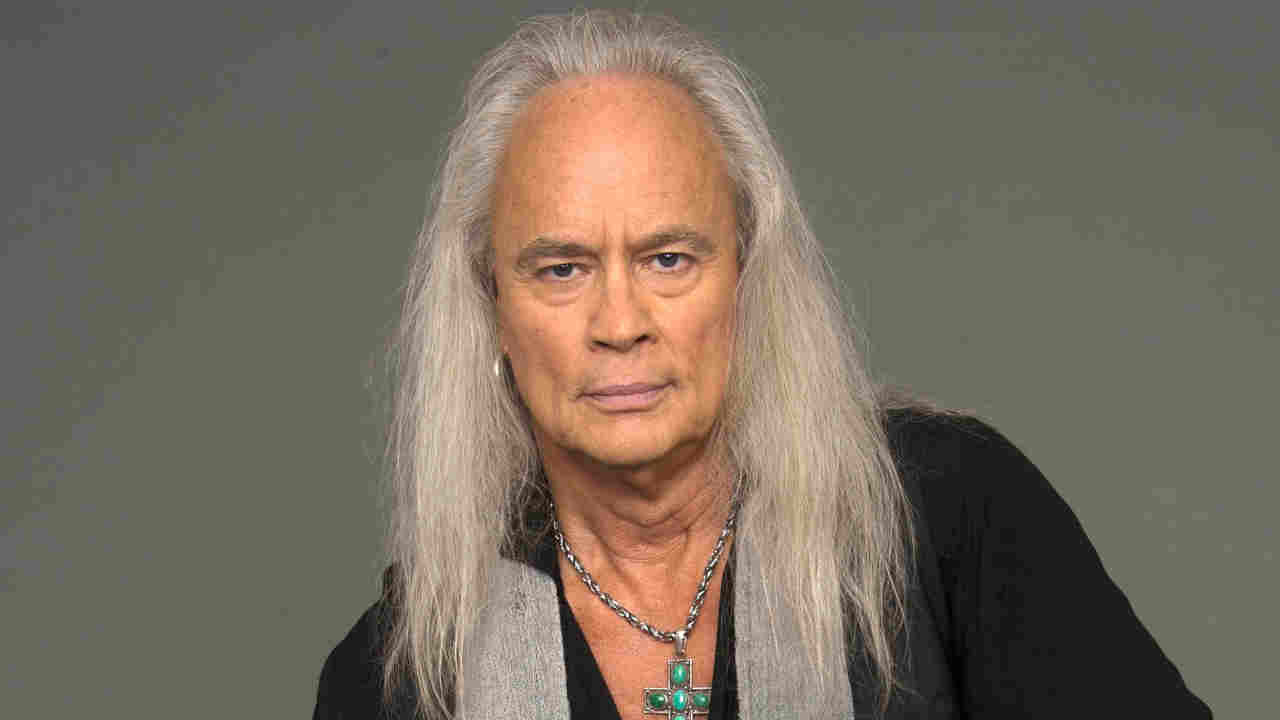

Enter Ron Geesin, an Ayrshire-born banjo player, pianist, poet and writer. Geesin had started his career in a jazz band in the early 60s. By 1970 he was composing TV soundtracks in his basement flat/studio in Notting Hill.

Mason met Geesin through a mutual friend, the Rolling Stones’ tour manager Sam Jonas Cutler. Geesin wasn’t familiar with Floyd’s music. And when he did hear some, he wasn’t impressed. “I called it ‘astral wanderings’,” he said.

Geesin also preferred opera to most rock’n’roll, and he took Mason, Gilmour and keyboard player Rick Wright to hear Wagner’s Parsifal at Covent Garden. “I think it’s significant that they all fell asleep,” he grumbled.

Still, Geesin was the obvious choice to compose the score. He and Waters were already writing music for a scientific documentary called The Body. Between them they crafted a soundtrack from conventional instruments and ‘human noises’ such as breathing, talking and farting. Atom Heart Mother would offer a similar fusion of ordinary and extraordinary sounds.

Talking in 2006, Geesin said Pink Floyd had only the vaguest idea of what they wanted. “As far as I can remember, Dave talked to me about the theme and Rick came round to my studio and we went through a few phrases for the vocal section. The Floyd then went off to play in America and left me to get on with it.”

Geesin composed his score in the midst of a heatwave, “stripped down to my underpants” in his Notting Hill basement. This half-naked Scotsman would play a vital role in Pink Floyd’s next album.

The early 1970s were a challenging time for classical session musicians – it was as if every long-haired rock group wanted cellos and tubas on their records. First The Beatles, then The Moody Blues, The Nice and Deep Purple. Now Pink Floyd.

Ron Geesin had just recorded a TV commercial with members of the New Philharmonic Orchestra, and they’d treated him with respect. But when Geesin and the Floyd reconvened at Abbey Road in June, the EMI Pops Orchestra regarded Ron as another clueless hippie, and made the session as difficult as possible. It didn’t help that an error in the score meant the first beat of the bar was absent, rendering it almost unplayable.

“For the more experienced director, it would have been considered a normal display of nerves and status-jostling and would have been put in its place,” Geesin said. “But I was a novice. I was not a conductor. You’d ask the EMI players a question and it was all, ‘You tell us… I don’t understand.’ One of the horn players was especially mouthy.”

When Geesin threatened to hit the mouthy horn player, he was told to leave. “They removed me,” he explained.

Geesin’s replacement was conductor John Alldis, a respected choral scholar. The contrary session musicians quickly fell in line, while Alldis’s choir contributed the track’s haunted-sounding, wordless vocals.

Waters’s description of the Atom Heart Mother suite’s opening movement (later titled Father’s Shout) as “plodding” is apt. But three minutes in, the plodding ends and Gilmour’s slide guitar takes over, underpinning Icelandic session man Hafliði Hallgrímsson’s lovely, mournful cello. In moments such as these you get a taste of what Pink Floyd would soon achieve on Meddle and The Dark Side Of The Moon.

On the fourth movement, Funky Dung, the guitar and Hammond organ play lazy tag on what sounds like a precursor to Any Colour You Like. The choir’s gospel-like vocals evoke those later heard on Eclipse. Geesin and Waters’s Give Birth To A Smile, from the soundtrack for The Body and included on The Early Years, also used female backing vocals, alongside the rest of an uncredited Pink Floyd.

Meanwhile, the suite’s fifth section, Mind Your Throats Please, merged Nick Mason’s distorted voice shouting “Silence in the studio!” with the sound of Rick Wright’s piano played through a Leslie speaker cabinet, a trick later used on Echoes.

Perhaps inevitably, Geesin was frustrated by the finished article. Under John Alldis’s direction, the brass had become softer, less aggressive. “It wasn’t how I’d envisaged it,” Geesin said, before conceding: “It was a good compromise.”

On June 27, Pink Floyd played the Bath Festival Of Blues And Progressive Music, joined by Alldis’s choir and the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble. They didn’t make it on stage until dawn, and Waters introduced their new suite as The Amazing Pudding. “It was a heavenly sound,” claimed the reviewer in Disc And Music Echo. It was less heavenly for a tuba player who had a pint of beer tipped into his instrument before the show.

A month later, Pink Floyd were back at Abbey Road to record the album’s second side. The creative freedom EMI allowed them seems unthinkable now, in the era of micromanaged, focus-group pop. Even though Floyd were producing themselves for the first time, any snooping EMI executive who turned up was given short shrift.

Tape operator Alan Parsons, who would later help engineer The Dark Side Of The Moon, recalled the time an executive dropped by the studio.

“Floyd had a general aversion to record company people,” Parsons said. “An A&R guy showed up, and Roger and Ron said: ‘We’ll play you a bit of the album.’”

Prior to his arrival, they’d hidden a turntable under the desk and proceeded to play an old 78rpm disc through the studio speakers. The A&R man looked baffled and walked out. “But we were all unable to keep a straight face.”

Nick Mason once said Pink Floyd “never threw any musical ideas away”. Ron Geesin recalls the four songs on the album’s second side developing from “scraps of things they had lying around”. And long-time Floyd watchers know that the second side contains some buried treasure.

It’s the lyrics that make Roger Waters’s delicate ballad If so fascinating. ‘If I were a good man I’d understand the spaces between friends,’ Waters declares. ‘If I were alone I’d cry…’

This was Floyd’s imperious spokesman showing a softer side. “We all have our insecurities,” said Ron Geesin. “I thought If was one of the brilliant gems.”

After all, Waters, like the rest of Pink Floyd, hadn’t forgotten Syd Barrett’s forced departure. While they were making Atom Heart Mother, the fragile Barrett was recording his second solo album next door.

Geesin was there the day Barrett appeared in Floyd’s studio. He sat on his hands, stared at his old bandmates for a few minutes and then disappeared. “He spun out again as quickly as he spun in.”

Next up was Rick Wright’s Summer ’68, a song about a casual encounter with a groupie, featuring the EMI Pops Orchestra’s buoyant brass. It’s a very human song on an often alien-sounding album.

“In the summer of ’68 there were groupies everywhere,” said a wistful Wright. “They’d come and look after you like a personal maid… and leave you with a dose of the clap.”

‘Human’ is also the key to David Gilmour’s charming Fat Old Sun. A very English hymn to the wonders of ‘summer evening birds’ and ‘new mown grass’, it suggests a snapshot of the Arcadian countryside set to music.

“It’s fantastically overlooked,” said Gilmour, who wanted the song included on the 2001 Floyd compilation Echoes. “Tried very hard to push the others… but they weren’t having it.”

The album ended with Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast, a meandering instrumental augmented by the sound of Floyd roadie Alan Styles cooking bacon, eggs and toast, and rendered in sumptuous quadrophonic sound. “One take went: ‘Egg Frying Take One,’ followed by, ‘Whoops!’ as the egg dropped,” recalled Parsons.

“Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast is quite interesting,” said Nick Mason, who considered the song his baby. “But in some ways, the sounds effects are the most interesting part.”

“It was the most thrown-together thing we’ve ever done,” remarked a rather dismissive Gilmour.

Fans would spend decades pondering what Atom Heart Mother’s filmic prog rock concerto, folky ballads and frying eggs actually meant. But nobody, including Pink Floyd, was entirely sure.

Hipgnosis’s Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell, who were commissioned to create the cover artwork, didn’t have a clue either. They proposed putting a cow on the cover almost as a joke, but the band loved the idea.

With its striking cover image in place, the group still needed a title for the album, and The Amazing Pudding failed to stick. Inspiration came on July 16, when Pink Floyd recorded a concert session for DJ John Peel (now included on Devi/Ation).

Former BBC producer Jeff Griffin was at the Beeb’s Paris Cinema studio that night. “John was reading the Evening Standard and Roger was looking over his shoulder,” Griffin revealed. “Peely said: ‘Come on, what’s the name of this piece? I bet you find something in the paper.’”

Also present was Ron Geesin, who insists it was he who told Waters to look in the newspaper. “I said: ‘Your title’s in there.’” And it was.

Waters leafed through the pages and stopped at a story headlined ‘Atom Heart Mother Named’, about a 56-year-old woman, who’d been fitted with a radioactive plutonium pacemaker. “Roger said: ‘That’s it! Atom Heart Mother!’ Which had nothing whatsoever to do with the music,” Griffin said, laughing. “We were saying: ‘Why?’ But the band said: ‘Why not?’”

Two days later, Pink Floyd headlined over Roy Harper, Kevin Ayers, the Edgar Broughton Band and more at a free concert in London’s Hyde Park. They performed Atom Heart Mother, again with the John Alldis Choir and the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble. But Ron Geesin walked out in tears. “The performance of the brass was terrible,” he said.

Geesin had co-written Atom Heart Mother, but he had to let it make its own way in the world. Pink Floyd’s manager Steve O’Rourke soon reminded him of the perpetual struggle between art and commerce. Geesin had divided his original score into movements, marked A to Q. “It was a practical necessity to see where I was going with the writing, but we all assumed it was one track.”

O’Rourke told him that due to Floyd’s US record deal the suite had to be divided into separately titled movements as quickly as possible: “Or else they’d only get paid publishing royalties on one song.” Between them, Geesin and Pink Floyd carved the piece up into six movements. Geesin suggested the title Father’s Shout after one of his heroes, US jazz pianist Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines. The group suggested other titles inspired by the ‘cow’ cover, including Funky Dung and Breast Milky. For monetary purposes, one song became six.

It turned out to be a shrewd move. Released on October 2, 1970, Atom Heart Mother reached No.1 in Britain, making it Floyd’s biggest seller yet. Beat Instrumental described it as “an utterly fantastic record”, and Circus magazine in the US (where it reached No.55) called it a “trip trip trip, a tippy top trip”.

Soon after its release, film director Stanley Kubrick asked if he could use the suite in his forthcoming dystopian drama A Clockwork Orange. But Kubrick wanted to edit the piece, and Floyd refused. The LP sleeve made a fleeting appearance in the movie.

These days Ron Geesin has mixed feelings about his most famous work. His next major assignment after AHM was the score for director John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday. Since then he has created sound and video installations and recorded some pioneering electronic music.

“I’d like to stand up and say: ‘Look here, world! I’ve done two thousand pieces of work, some of which I think are much better than Atom Heart Mother, but no one has heard them.”

It also bugged him a little that he was never given a co-credit on the album. “Though that was never discussed with the group,” he explained.

The Atom Heart Mother suite became a fixture of Pink Floyd’s live set throughout 1970 and ’71, until deposed by their next side-long epic, Echoes. Roger Waters performed If on his early solo tours, and David Gilmour reprised Fat Old Sun for his 2006 On An Island tour. However, the band members have often been critical of the title track. Waters called it “rubbish”; Gilmour once described it as “absolute crap”.

Still, time’s a great healer. Gilmour joined Geesin to perform the suite at the 2008 Chelsea Festival, with cellist Caroline Dale, a chamber choir, brass players from the Royal College Of Music and an Italian Pink Floyd tribute band, Mun Floyd. Geesin resisted the temptation to tamper too much with the score beforehand. “It’s a formed work,” he said. “Don’t poke it about too much or it’ll fall apart.”

Whatever misgivings Pink Floyd might have about Atom Heart Mother, the album turned out to be a crucial step along the road to their world-conquering The Dark Side Of The Moon. But it’s more than that. Atom Heart Mother is a celebration of the wilfully experimental Pink Floyd. Before the big hits and the even bigger money, it’s the sound of a contrary art-rock band making an ungodly racket in Abbey Road studios, while their EMI paymasters wondered what the hell they were doing.

Like that Friesian peering balefully from the record’s front cover, the music on Atom Heart Mother challenges and confuses, but somehow draws you in. And nearly five decades on, Pink Floyd’s “weird shit”, as David Gilmour put it, has never sounded better.

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.