Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

On July 26, 1977, bang in the middle of the summer of punk, a flatbed Ford truck pulls up outside the London Hilton where the cream of the CBS record company are holding a high-level conference. A slight fellow sporting geeky Buddy Holly glasses and wearing a dark shirt and tie emerges from the passenger side clutching a guitar and a small amplifier. He sets himself up busker-style and proceeds to blast the bemused executives with a selection of rapid-fire, snarling ditties which he intersperses with the barked command: “I am Elvis Costello. Sign me!”

Meanwhile, West End police have just received an anonymous tip-off from a man with a decidedly Irish accent telling them that another Irishman of dodgy countenance is causing trouble on Park Lane. With the IRA’s bombing campaign subjecting London to non-stop paranoia and the Queen’s Silver Jubilee shenanigans turning England into a virtual police state, alarm bells go off. An unmarked police car arrives and promptly arrests Costello, who turns Queen’s Evidence and tells them to call his employers, Stiff Records of Alexander Street W2. But when the desk sergeant calls Stiff MD Dave Robinson – who had made the phone call to the fuzz – he tells them he has no idea who Costello is. The hapless Elvis is promptly arrested for causing an obstruction and spends the night fuming in the cells.

“Was he pissed off!” Robinson now recalls. “He got the hump. But then he did get signed to CBS, so that publicity stunt not only got us on the news and in the next day’s papers, it gave him a career.”

Stiff had creative energy, and we became synonymous with that ‘take it to the Nth degree’ attitude, at a time when the business was dominated by the Eagles.

Mickey Gallagher, the Blockheads

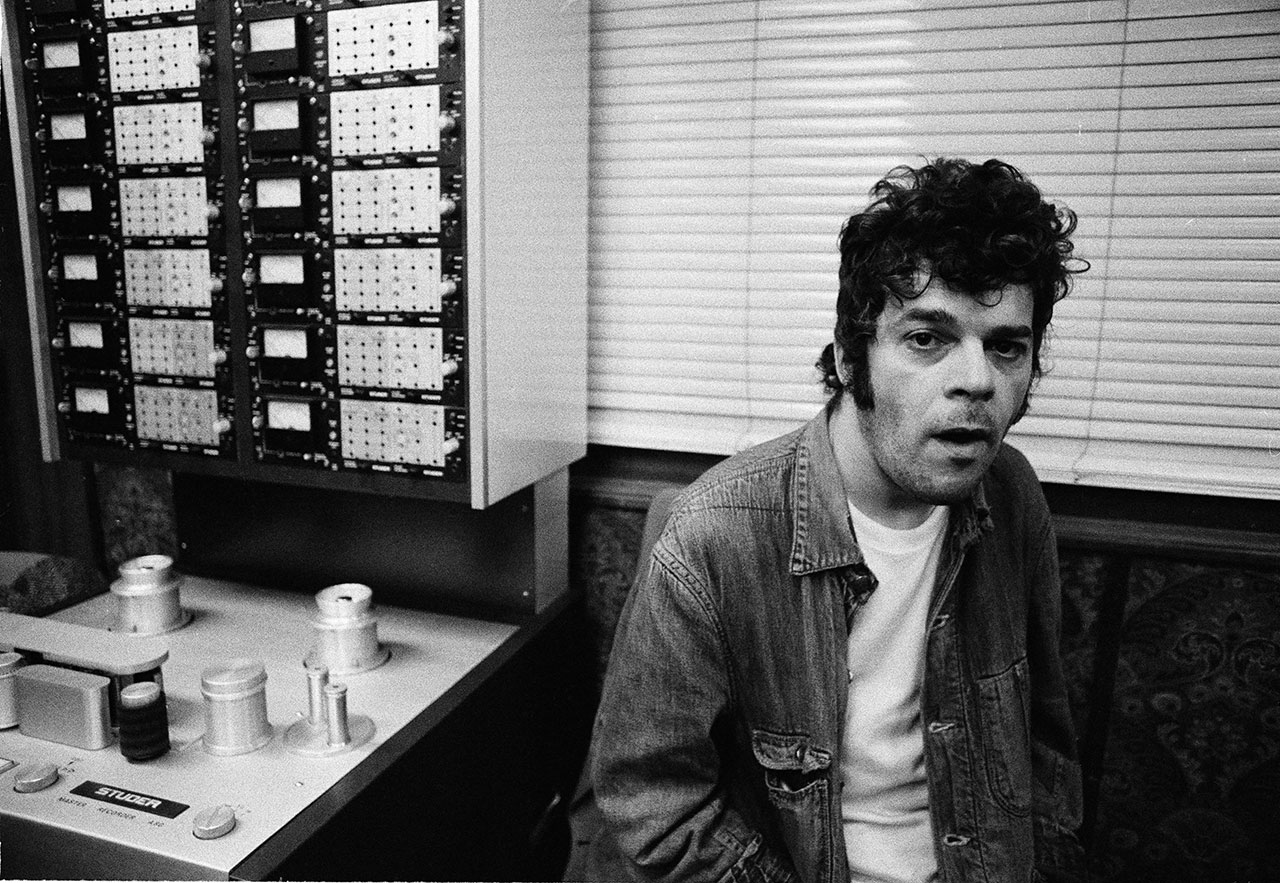

Stiff Records was the brainchild of Robinson and his partner Andrew Jakeman, aka Jake Riviera, a couple of sharp-eyed wide-boy hustlers with music business form of their own as managers of the bands Kilburn And The High Roads and Chilli Willi And The Red Hot Peppers respectively. Their acquaintance became cemented in 1975 when English music was snowed under by nondescript guitar bands in thrall to far superior American music, while our local struggling pub rockers operated on the equivalent of the 1950s skittle circuit. Times were dire. Punk was fermenting, if not yet visible, but the smell of revolution was abroad. Robinson decided to exploit this deadly malaise with shock tactics that changed British music completely, and launched the independent music scene.

“There were five weekly music papers desperate for copy,” Robinson points out. “Yet the record companies were clueless hippies. Jake was high on the hog after coming back from America after road managing Dr Feelgood [the Canvey Island R&B nutters who inadvertently kick-started punk], and we’d both been impressed by the growth of small labels in the USA. We were a couple of smart alecs with an ear for a slogan. By spring 1976 we were ready to go.”

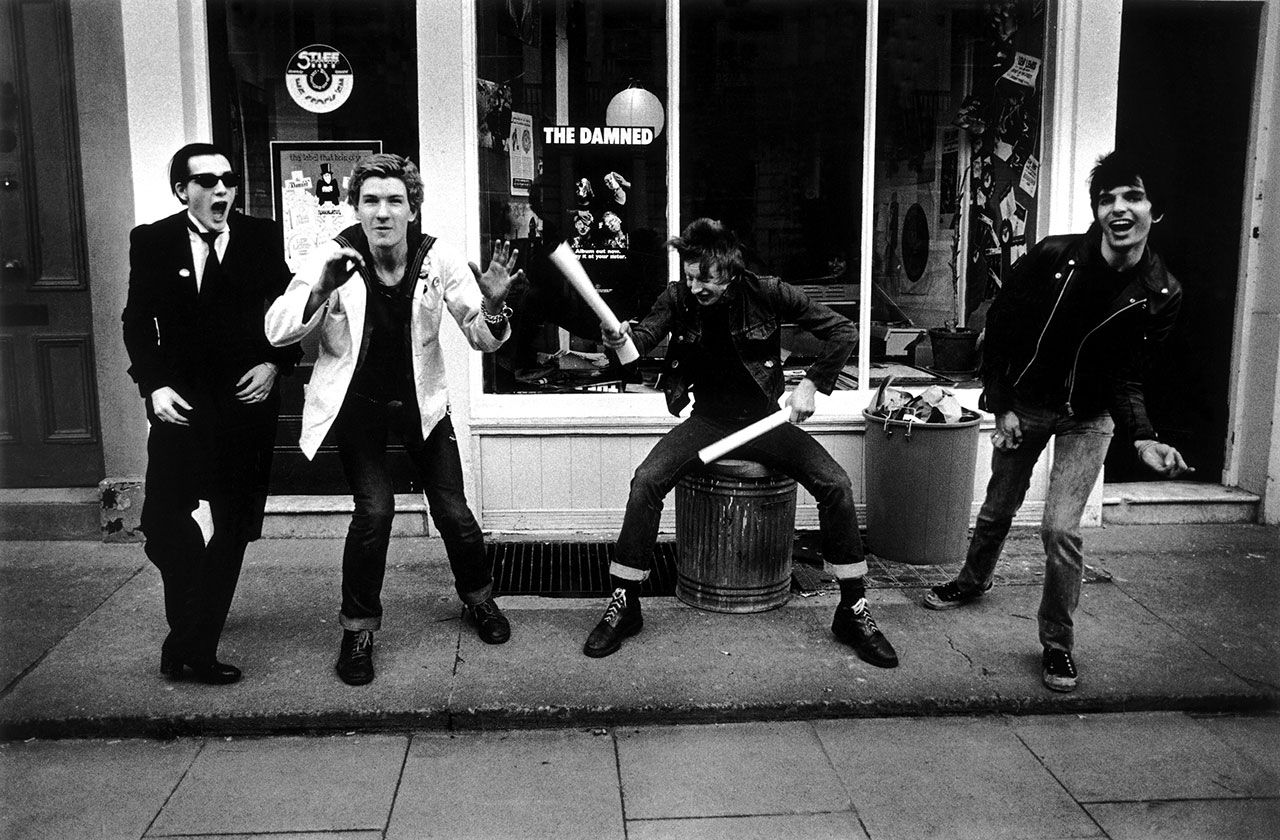

Stiff was originally called Demon, but the rock biz phrase ‘It’s a stiff!’ provided a funnier alternative for their stable of misfits. In the long hot summer of 1976 Stiff released their debut single, So It Goes, by former Brinsley Schwartz bassist Nick Lowe, and started fly-posting London with posters declaring ‘If it ain’t Stiff It ain’t worth a fuck’. They also signed The Damned, whose single New Rose became the first officially recognised English punk rock record.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Riviera was shepherding The Damned around Britain as part of the Sex Pistols’ ill-fated Anarchy In The UK tour (which also included the Clash as bill openers), but he soon fell out with Pistols mentor Malcolm McLaren. Renowned for his volatile temper and an argumentative streak akin to an oxyacetylene blowtorch, Riviera was adamant that The Damned would trump Johnny Rotten’s mob. In the ensuing war of words Damned bassist Captain Sensible poured petrol on the rivalry when he declared that the Pistols’ single Anarchy In The UK was “Utter shit. We pissed ourselves. It sounded like some redundant Bad Company out-take, with old man Steptoe singing over the top.”

The Damned, the self-styled Bash Street Kids of punk, embodied Stiff’s unpretentious attitude. While McLaren cloaked his charges in situationist theories, Riviera and Robinson were peddling a B-movie/pulp-fiction brand of hard-boiled wit. ‘When you kill time you murder success’ became their mantra. They had it printed on badges. The five music papers acquiesced.

Costello was Stiff Records’ critics’ darling. Born Declan McManus, he’d been signed after demoing 36 songs in three hours at Riviera’s flat. “Jake didn’t like him originally, but we told him to change his name and we’d give it a go”, Robinson says. “Jake came up with ‘Elvis’ because he knew that would piss everyone off. I added the Costello, which was his mother’s maiden name, and told him to get rid of his frameless specs for frames – which became his trademark. Elvis would have done anything he was told then just to get signed. Same with The Damned. They were contrary fuckers but they didn’t want to spend their lives as a semi-pro outfit either. Those people were desperate to be on Stiff because otherwise they were going nowhere.”

The Riviera-Robinson axis lasted for two years. There were many altercations. Robinson remembers: “Jake lost his rag with me once so I took him into the back room, and he was prodding me. I’m slow to burn but I’ve a bad temper. We certainly weren’t good cop/bad cop. Jake had been in the pub, and there was plenty of chemical abuse around, amphetamine sulphate being rife; we all did it… Anyway, I pinned him against the wall and said: ‘Don’t ever talk to me like that again, because you’ll need a lot of people to pull me off, and when they have done you’ll be in a very terrible state.’

“Jake used to shout a lot. His skill was his cutting edge. When he walked away from an argument lesser men felt their bits dropping off. The Police’s manager Miles Copeland once made the mistake of going backstage to show off Sting’s success in America. We almost signed them, but passed because they had a shit French guitarist [Henry Padovani, later replaced by Andy Summers]. Miles made a big mistake. You do not beard Jake when he’s in front of Elvis, because he’ll threaten you when he’s got an audience. He ripped Copeland to pieces. He insulted his band, his clothes and his stupid accent. Miles left the room feeling like a fucking idiot. He called me and asked: ‘Why? What did I do?’ Well, hard luck, Miles. Don’t rub Jake up the wrong way in a dressing room. He’s a bully. You’ve got to stand up to him.”

In autumn 1977 a road show called the Stiffs Live Stiffs tour set off around the UK with Costello, Wreckless Eric, Nick Lowe, Larry Wallis and Ian Dury And The Blockheads in tow. While Dury was gaining many plaudits, Jake and Elvis hatched a plot to leave Stiff and sign to a newly formed label called Radar Records, bankrolled by Warner Brothers.

Robinson was furious. “Our finances were in good shape; we had the CBS deal, and the future looked bright for artists like Ian Dury and Lene Lovich [a prototype rag-doll screecher who begat Cyndi Lauper]. I tried to talk him round, but then I thought: ‘Oh fuck it. Let ’em go.’

“Of course I was annoyed. But I kept the office. And Jake was getting difficult. He’d burnt a lot of bridges even as we stood on them. Lots of people hated us. And there were some discrepancies over advertising: we’d overcooked the books to the tune of 160 grand. But we still had The Damned, and Dury was breaking. We were influential alright. Tony Wilson started the Manchester TV show So It Goes as a result of hearing Nick Lowe. And we inspired Rough Trade and the whole picture sleeve revolution, thanks to our graphic department, headed up by Barney Bubbles, who was mad as a fruitcake but a genius designer.”

In that heady period Stiff got rid of the American major-label sludge and cashed in on the whole street rock alternative of punk and new wave. They were only a flea on the back of a dinosaur. And while they were starting to bite hard, well, so were the creditors.

Salvation arrived in the unlikely shape of Ian Dury. One of the last endemic polio victims in post-war Britain, Dury’s working-class fusion of vaudeville/music-hall nonsense, rhyming slang and his band The Blockheads’ vicious swing made him Stiff’s first superstar. “We went big on [Dury’s] New Boots And Panties!! album,” Robinson recalls. “Luckily Ian gave fantastic copy. We came up with the slogan ‘Give Up Smoking, Give Us Your Money’ for him, and the rest fell into place. Here was this ex-art school nobody who suddenly took off with Reasons To Be Cheerful and Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick.”

Dury’s fascination with the gangster underworld, and his own chippy propensity for belittling those who he took a dislike to meant that he was surrounded by East End heavies; his minder Fred Rowe, a big, black former villain, became the most obvious example in his freakish entourage.

Naturally aggressive on account of his disability, and the fact he’d had the shit beaten out of him at a home for the mentally disturbed where he was forced into callipers, Duty’s immense talent was offset by a pushy and bullying nature. According to Robinson Dury was fine in one-to-one relationships, but feed him with hashish and brandy and the demons emerged. “He used to antagonise people in bars and get beaten up, so I found him Rowe for his own protection. When the Sex and Drugs And Rock’n’Roll single came out he started making serious money, and Fred had to save his arse more and more frequently.

“Trouble was, his manager, Pete Jenner [who had looked after Pink Floyd], was of the don’t-tell-the-artist-the-truth school. It went pear-shaped when his album Laughter came out [1980], and we laughed him out the door because it was so poor.”

Blockheads keyboards player Mickey Gallagher has great affection for his time with Stiff, while agreeing that Dury could be bloody hard work. “The first Stiff tour was a great success for us,” he says. “We were this eccentric bunch of characters who’d never have seen the light of day without them [the label]. They had creative energy, and we became synonymous with that ‘take it to the Nth degree’ attitude, at a time when the business was dominated by the Eagles – so no change there.

“Ian was an awkward bugger. The first thousand pounds he made with the Kilburns, he burnt. Ian saw himself as the artist. He had an odd temperament; he wouldn’t pander to anyone. He was obsessed with [60s London gangster brothers] the Krays, and if he’d had all his faculties I’ve no doubt he would have been a very nasty piece of work indeed. He made people cry because he was heavy mentally; very caustic. He’d make grown men weep. He’d dig at your family, at your kids, and you couldn’t hit him because he was disabled. Lots of mind games ensued, especially towards any women around the band. He hated seeing any wives or girlfriends. He was a misogynist, so the Blockheads became a boys’ club. That wasn’t pleasant.”

Evidently, to work with Dury you had to take him warts and all. What made him so obnoxious also gave the Blockheads their edge.

“He was a fantastic frontman in front of a very professional musical unit,” Gallagher says. “He expounded violence, so the atmosphere at the gigs was full of testosterone. It was fantastic to be a part of that, but later on, when he’d had too much Guinness and Budweiser, the Devil would come out. He used to bring people down when they wanted to be celebrating. It was a decadent time, lots of sex and drugs coupled with an ultra-punk, fuck-everything attitude. Stiff exploited that brilliantly – they were superb for the artist – although when they locked in with EMI they lost the creative playground. The changing atmosphere affected Ian more than us. At his peak he was a stimulating man, great to be around when he was on form. I liked him, but I never loved him.”

Not all of Stiff’s artists look back on their time on the label with such equanimity. Edward Tudor-Pole, of Tenpole Tudor infamy, had appeared in the Sex Pistols film, playing a cinema usher singing his own composition Who Killed Bambi? based on screenwriter Roger Ebert’s original movie title. Edward was mooted as a replacement for Johnny Rotten when the Pistols fragmented after the Sid Vicious debacle, but decided to front his own band, who he dressed up in suits of armour and any other period costumes he could wangle out of theatrical costumiers. Ideal Stiff fodder, then?

“Not at all,” reckons Eddie today, sounding remarkably like Terry Thomas. “Being signed to Dave Robinson was like entrusting your prized Stradivarius to a gorilla; it just gets bashed about. People harp on about the family atmosphere, but they were very unfriendly to me. I didn’t notice any friendliness. Everyone was cowering in the corner. They hated my eccentricities, didn’t get me at all. I thought they were a bunch of barrow boys. They knew we were a brilliant live band, but everything else was camouflage and advertising.”

Unrepentant to this day, Tudor-Pole maintains that Robinson was a despot and a martinet, as he lampoons his accent: “‘Just cos you’ve had a hit record doesn’t make you an artist.’ Deeply depressing. I suppose Dave could be charming. It was good and bad. I have to thank him for signing me. We played a gig at Dingwalls, sort of a showcase in front of the industry, and someone threw a glass at me because they thought I was taking the piss out of rockabilly. I had blood pouring down my face while we did a cover of My Girl – it was fucking brilliant. The only person who came to tend to my wounds was Robinson, and so we signed to him by default.”

Despite European success with the singles Swords Of A Thousand Men and Wunderbar, Tenpole Tudor fell out of grace and favour with their paymasters. During the 1980 Son Of Stiff coach tour, Edward wrote Swords… on the travelling toilet – “a fucking cess pit, but the only refuge for some p and q.” Unfortunately, when the tour continued in America the singer made some choice remarks about the death of John Lennon and his credit started to run out.

The Members, whose Sounds Of The Suburbs was a big hit for Virgin records, released one single for Stiff, Solitary Confinement, in 1978. Their lead singer Nick Tesco has mixed feelings about his sojourn on Alexander Street: “They didn’t make much time or effort for us, although we were a zeitgeist band for them. Still, I was proud to be on their label. We had a single out with a picture sleeve, and people are still impressed by that. Of course, we didn’t make any money, but that didn’t seem to be the point. Their attitude was: throw enough shit at the wall, some of it will stick. And I liked the way they sold records out of the back of a van and pressed the records up in reggae studios. The best thing about being on Stiff was that they were close to the epicentre of Ladbroke Grove, so it was easy for a nose and weed merchant to get the essential wiring that made punk work.”

Before the Members emerged, Stiff had signed the Adverts, after Jake Riviera and Nick Lowe took up a recommendation from Brian James of The Damned to catch them at the Roxy in Covent Garden, the club that became the spawning ground for would-be punk heroes. The Adverts’ Tim ‘TV’ Smith has fond(ish) memories of the label.

“It was a thrill,” Smith says. “I was already aware of Lowe and Costello, and when they put us together with the producer Larry Wallis, who had released Police Car for them, we were delighted to be on board. The single we made, One Chord Wonders, got great reviews, and loads of airplay on John Peel, but it was a failure commercially. I enjoyed the kudos of Stiff. The problem was they were so eclectic, and The Damned were always going to be their number one punk act. We were always second-best.”

The Adverts ran into a major stumbling block when they realised that TV Smith’s girlfriend and band bassist Gaye Advert was being used to sell the band to a music media who thought ‘Tits Mean Business’. “Jake’s thing was marketing, and they had a photo of Gaye – a head shot – on the single sleeve. We hadn’t expected that. The music press were just as bad. It was so misogynistic that it caused huge ructions in the band. Gaye was so annoyed she refused to have her picture taken at all later on, because she was being used as a sex symbol, like Debbie Harry.”

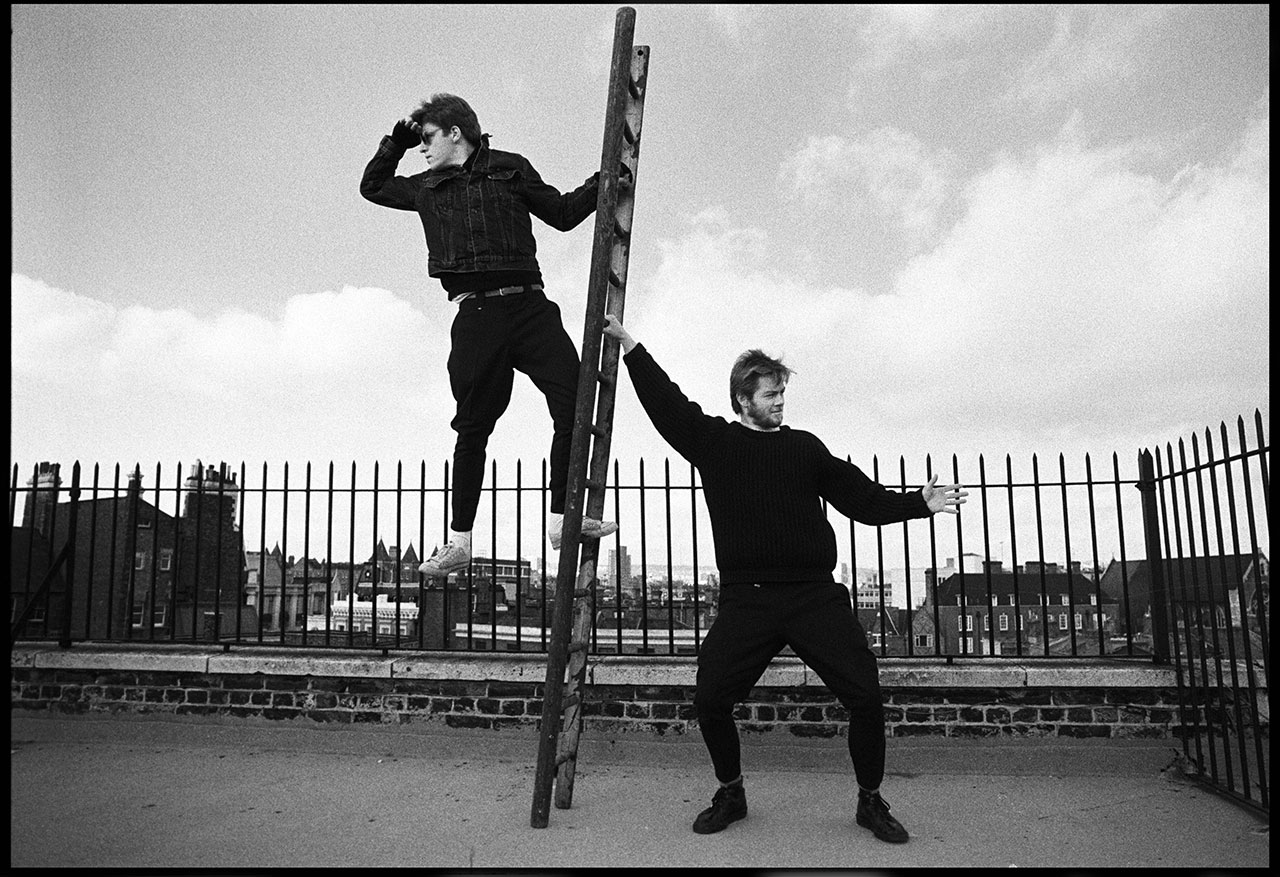

Today TV Smith credits Stiff for their sparky in-house wit. “I liked the anarchism of the label; they had funny slogans; the records were all one-offs that made you laugh. And considering I’d moved to London from Okehampton in Devon, where nothing was going on at all, it was all a step up the ladder.”

Stiff’s transformation from pub rock to street rock, via the maverick sensibilities of Ian Dury, reached fruition when they signed Madness. Camden Town’s Nutty Boys coincided with a seating in the music industry, as punk’s DIY ethics finally informed the mainstream. Madness enjoyed a straight run of 23 Top 20 hits, and that success allowed Robinson to explore the next medium before compact discs: the pop video.

Despite any unasked-for associations of the National Front and the British Movement with Madness and the so-called Two Tone scene, Stiff shed its reputation as a cottage industry label and made serious money via licensing deals with EMI, Island Records and Trevor Horn’s ZTT, all of which distanced Dave Robinson from his original objectives, ultimately sidelining the label as something whose time was up.

The cheap clocks they’d bought for 50 pence a unit, proclaiming When You Kill Time You Murder Success, seemed rather quaint once Frankie Goes To Hollywood and the whole E-soaked dance movement hit the sprung dance floors of Britain.

Different times also meant different drugs. According to Robinson the momentum had swung back to the majors, who were now adept at swallowing the indie labels that threatened their stranglehold. “We’d missed out on the Police and Dire Straits, which was annoying, but I really wanted to sign the Stray Cats. I’d seen how their psychobilly thing went down with the Madness fans. I went to the Portobello Hotel with a contract, and their singer Brian Setzer agreed to go with us. Unfortunately they’d run up a £40,000 cocaine bill with a record executive, and I wouldn’t undo that debt.

“Everyone was off their heads in the 1980s. I went into one record company one day and the entire staff were off their fucking boxes, in a state of high cocaine tension. I asked a bod what was going on and he told me: ‘There’s your man’. It was [a very famous British movie director]. ‘He’s a runner for the company and he’s a cocaine dealer’.”

Aghast at what he saw, Robinson realised the music business was condemned to repeating a history of mistakes. Having been Jimi Hendrix’s road manager in the late 60s, he’d seen the full cycle. “Hendrix was the most phenomenal talent and person I ever dealt with, but he was also the most stubborn and stupid. When I worked for him he had huge success but no money. I had to find him a flat in London, and I soon realised he knew nothing about his financial affairs. I was banking millions of his money, because I had the briefcase with the receipts in it, into a company in the Bahamas, and yet he was virtually broke.”

Now, a rock generation down the line, Robinson was about to realise that very few lessons had been learned. “Coke was rife, but it was a useless drug; occasionally good at parties. I was very leery about all that stuff. For fuck’s sake, Phil Lynott is buried three graves down from my mother! All that star bullshit! You’ll get burnt to a crisp unless you’ve got strong management. Of all the things at Stiff, I’m proudest of coming up with the slogan: A Star is Somebody Nobody Tells the Truth To.”

Today Dave Robinson thinks Stiff’s legacy could be embodied in a simple home truth: you could be this, or you could be that. Or you could be sensible – and have a lifetime career.

Or, in the words of the sozzled Irish drummer, who witnessed Robinson and Riviera coming close to fisticuffs in a Ladbroke Grove pub one evening in 1976, thus inspiring the little label that changed the music industry forever: if it ain’t stiff, mate, it ain’t worth a fook.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.