The State of the Union: Americana 2014

Lucinda Williams, Cory Branan, Justin Townes Earle &Chuck Ragan: four singers, four sounds, one spiritual home.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

From the ex-punk to the scion of country royalty, this is what American roots music looks like in 2014.

1. THE GODMOTHER: LUCINDA WILLIAMS

Great Things Come To Those Who Wait

For the longest time, Lucinda Williams couldn’t get a break. CBS Records in Nashville told her she was too rock for country; in LA she was deemed too country for rock. She made rural blues records that nobody bought. Or, in the case of 1988’s self-titled third album, crafted fine roots music that arrived too early for the Americana boom. Williams found champions in the form of Tom Petty and Emmylou Harris, both of whom covered her songs. But she seemed destined for a career slapped with that most unwelcome of labels: the cult artist.

Then something happened. In 1993 Mary Chapin Carpenter recorded a version of Passionate Kisses that became a country hit. It landed Williams a Grammy for Best Country Song.

The real lift-off moment, though, came with the release of her 1998 album Car Wheels On A Gravel Road. Co-produced by Steve Earle, it was a perfect assimilation of gospel, country and stinging blues, driven by Williams’s ear for narrative and her ability to press raw emotion into poetic song. The album went gold, bagged her another Grammy and landed her a major tour with another admirer, Bob Dylan. By then she’d been at it for well over 20 years.

Not that she’d been unduly troubled about her slow ascent. “It wasn’t until I moved to Los Angeles in 1985 that I was exposed to the music business at all,” Williams explains. “Before that I didn’t have a publisher or manager. But I’d been playing for years, honing my craft. I knew I wanted to do this for a living, but I wasn’t concerned about making it happen overnight.”

The Louisiana-born daughter of poet and author Miller Williams, she grew up surrounded by literature and music. Her father’s vocation took her to Mexico, Mississippi, Georgia and Arkansas, which gave her an early appreciation of the migratory aspects of song.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

She began in the early 70s as a folkie, playing regularly amid the strip clubs in New Orleans, though her creative spirit sparked when she found the blues and, especially, Robert Johnson. Her 1979 debut album, Ramblin’ On My Mind, was a collection of folk, blues and country covers, recorded in Mississippi. That was followed 12 months later by the all-original Happy Woman Blues. Neither record sold.

It would be another eight years before her third album, Lucinda Williams. The grainy burr of her voice, allied to the burning intensity of literate songs about pain and desire, suggested she’d made a striking artistic leap during the interim.

The ever-meticulous Williams took until 1992 to release Sweet Old World. It was another six years before Car Wheels On A Gravel Road. But while the latter’s success provided her with a major point of arrival, it only made her next choice of destination that much more difficult. “I was almost frozen with fear over how to follow Car Wheels,” she admits. “It kind of locked me up. I was so worried about being forced to write more narrative songs like Drunken Angel and Lake Charles and Greenville. So when I wrote Essence [2001] I came up with things like Steal Your Love and Are You Down, songs that relied more on the music than the lyrics. I started letting myself go into another area of songwriting. And once I did that it opened a whole other door.”

The spare intimacy of Essence – whose title song features a cameo from Ryan Adams – shifted the perception of Williams further. She was awarded a third Grammy, for the single Get Right With God. On 2003’s World Without Tears she changed tack once more, jolting electric blues and skittery country-rock into fresh forms.

Williams’s latest record is Down Where The Spirit Meets The Bone. A dazzling double album, released on her own Highway 20 label, it features guests Tony Joe White, Ian McLagan, Jakob Dylan and guitarist Bill Frisell. Its dominant strain is a swampy southern twang. And while the themes – mortality, love, longing, salvation – may be familiar there’s also a conciliatory feel to many of the songs, as if she’s made some kind of peace with the world she surveys. “I was consciously trying to go for more upbeat styles in my writing,” Williams says. “More rock songs or up-tempo things. It’s a lot easier for me to write ballads and slow songs, so I wanted there to be more of what I refer to as country-soul. One interviewer said to me: ‘You don’t seem as tortured on this album.’”

Now 61, Williams appears to be in the prime of her songwriting life. Where once she was a painstaking perfectionist, now she allows herself more spontaneity and freedom. “The biggest and most traumatic event in my life was when my mother passed away,” she says, “which was right around the time of West [2007]. It just seemed to open up this cataclysmic thing and I started writing a lot more. I’m certainly a lot more confident now. Like a lot of things, if you’re lucky you get better as you get older.”

_Down Where The Spirit Meets The Bone is out now via Highway 20.__ _

_ _

_ _

_ _

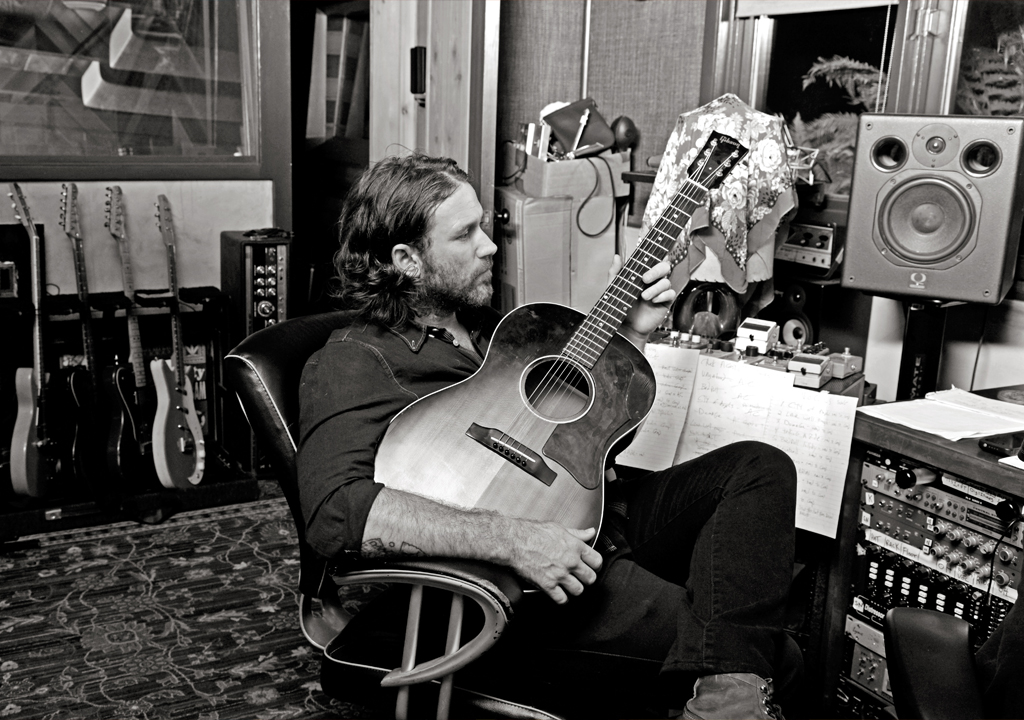

2. THE MONGREL: CORY BRANAN

Happy To Be A No-Hit Wonder

_ _

“The term ‘singer-songwriter’ feels like a toe tag to me,” Cory Branan says with a laugh. “But then all these stylistic phrases are cringeworthy, in their own ways. I just started a long time ago calling what I do ‘mutt music’.”

At first glance, Branan may appear to be of the typical pedigree – just another bearded dude with jeans and a Taylor acoustic. But although he admits he digs the occasional Gordon Lightfoot tune, he’s one of a growing breed of troubadours who are subverting the genre with a raucous spirit that’s more CBGB than Laurel Canyon.

“I’m a blend of the mess that I grew up in,” he says. “This legacy of Memphis and Mississippi, country and gospel, because I’m from the south. At the same time, I was this little hood rat kid glued to MTV. All of this music was coming at me really piecemeal, Prince and Eazy-E at the same time as Minutemen. Later I found artists like John Prine and Tom T Hall.”

Those disparate influences fuse together on Branan’s latest album, No Hit Wonder. Kicking off with the Stones-y swagger of You Make Me and the revved-up rush of the title track, it winds through a rockabilly-tattooed Sour Mash, the Vaudevillian charmer C’mon Shadow and the honky-tonkin’ All The Rivers In Colorado, before wrapping up with the Zydeco-flavored Daddy Was A Skywriter and the Little Feat-ish The Meantime Blues. The through-line to this musical eclecticism is Branan’s ultrasmart lyric writing, full of razor-sharp lines and freshly turned phrases. “I don’t have much of a singing voice, but I try to write the crap out of the songs,” he says.

Branan’s zig-zag course to solo singer-songwriterdom started when he was a 12-year-old budding metal shredder. “But when I was fourteen my dad took me to a guitar clinic at a local music store, with Elliot Easton, the guy who played with The Cars. It was the first time I’d ever been around a rock star, and he was totally down to earth. I just liked the guy. And when I saw the tasteful, cool way he played, it did something to me. I thought, ‘Yeah, there it is.’”

Through his teens, Branan apprenticed through a string of “some really awful bands – whoever wanted me.” In his early twenties, tiring of the “playground politics and arguments over where you’re going to eat lunch” that come with touring in a band, he started moonlighting solo at open-mic nights, first playing covers by Neil Young and Lemonheads, then tentatively debuting his own songs. “The reason I was so nervous at first playing and singing was either I’d be spazzy and weird and all over the place, or I’d throw up.

“But over time I found a way to work my spazziness and nervous energy into the show and play off the crowd. I remember when I saw Todd Snider early on, it clicked for me that you can take the elements of a given room and a given crowd and make that an equal part of the night. You can work with that as a solo performer, telling stories, making jokes. You can really pivot and deliver. Use dynamics. If I want to push a line, or drag it, or drop the music out, I can. Not to get too heavy about it, but Lorca, the poet, talked about this thing of ‘duende’. It’s like the equivalent of the Greek muse, but it means ‘wrestling with the angel’. It can only happen in a few art forms, like dance and music, because it unfolds in real time. Capturing the unique moment. It’s never going to be like that again. That’s what happens on a good night.”

All of which, Branan says, makes fixing 12 tunes into the grooves of an album such a challenge. “People will ask me: ‘Why don’t you record an album like your live show?’ Well, I will record a stripped-down record at some point but, trust me, you don’t want to hear what I do live on your stereo. It would be the most annoying thing in the world, because it’s very in-the-moment, specific to the night and venue. Tempos would drag, volumes would change. It would be jarring.”

On latest album The No-Hit Wonder, taking songs from the past two years, Branan found himself gravitating towards those that felt right up the middle. “I think it’s more of a roots record,” he says. “I went home to take care of my dad in the last months of his life, and in the middle of that I established stronger ties to where I grew up, around Mississippi and Memphis. It wasn’t a conscious decision, but I think this turned me back towards the country and gospel music I grew up with.”

Following that direction, he teamed up with producer Paul Ebersold. The pair agreed they wanted a full band sound that kicked through the speakers but still had headroom. “A sound where you can hear the players play,” adds Branan. Ebersold assembled a team of young session lions in Nashville, including the ace rhythm section of drummer Jon Radford and bassist Adam Gardner, plus Americana darlings such as Caitlin Rose and Jason Isbell.

“Paul is a Memphis boy, but we cut the record in Nashville, where I’m living now,” says Branan. “So I got the best of both worlds. There’s a spontaneity to the recording process, not over-thinking, capturing something fast and loose. Spontaneity with precision.”

While Branan looks forward to a few local shows with the same studio band, he’ll be hitting the road with just his acoustic guitar. “It’s fiscal necessity,” he says. And he admits that the view from his van window is slightly different now. “I still tour just as much, but the decision to be a lifer is a decision now. Before, I felt like I didn’t have a choice. I was compelled to do it. And now, with family and a true home, it puts it in stark contrast, the choice to drive away from that home for weeks at a time.”

And as he ventures out, what does he hope listeners get from The No-Hit Wonder (the title is a tribute to his fellow singer-songwriters who are fighting the good fight without radio play and publicity budgets)? “I hope people get some calories,” Branan says with a laugh. “I hope there’s enough meat in there. I’m trying to write accessible, popular songs that are there on the first listen, but I also put a lot of work into making them nuanced and worth repeat listenings.”

No-Hit Wonder is out now on Bloodshot.

_ _

_ _

3. THE PRODIGAL SON: JUSTIN TOWNES EARLE

The Apple Hasn’t Fallen Far From The Tree

In 2012, Justin Townes Earle was ideally set. His fourth album, Nothing’s Gonna Change The Way You Feel About Me Now, marked another creative surge for a songwriter who was fast gaining traction as one of the most distinctive American voices out there. Then things started to go awry.

“The last two years have been a roller-coaster,” he says. “I had a nasty break-up with somebody who turned out to be a sociopath. I was thirty-one years old with a long string of failed relationships and I was really down. The only thing going for me was my career. But I wasn’t working because I had trouble with my old record company. But an amazing thing happened when I met my wife. My whole life changed from that very moment.”

The result of Earle’s new-found surety is the album Single Mothers, a masterful blend of country, white gospel and rolling R&B, played with an economy that posits his fabulously emotive baritone front and centre. The record also serves as a tribute to the other influential woman in his life, mum Carol-Ann Hunter: “She raised me and did what a man should’ve done. She was a roadie and drove a truck, because it was the best money she could make. My mom worked her ass off. What I am today is way more because of her than my father.”

His father, of course, is fêted songwriter Steve Earle, who left Carol-Ann when Justin was two years old. Being the product of a Nashville legend and a broken home, allied to a self-destructive personality, made for a turbulent early life. Justin was using heroin at the age of 12. The remainder of his teens was marked by petty crime, drinking and serial drug use. By his early 20s he’d OD’d several times.

Unsurprisingly, it was music that offered a respite. Earle adored Springsteen and The Replacements. But it was Nirvana’s unplugged version of Leadbelly’s Where Did You Sleep Last Night that proved an epiphany: “Suddenly it all made sense to me. Everybody was taking things from the generation that had gone before. So I threw away my electric guitar and bought myself an acoustic one.” His switch to country music and set the template for 2008’s ironically titled debut The Good Life.

Earle has been free of hard drugs for some time now, and sober since 2010. Not that Single Mothers is the work of a man who’s entirely free of struggle. “I’ve seen a lot of people die around me,” he says. “A lot of my life has been complicated and hard and fucked-up, so it’s going to take a while to weed all that out. Touring, writing and making records are all hard, but I’m definitely a lot more relaxed as a songwriter. It’s the only thing I was ever good at.”

_Single Mothers is out now on Vagrant. _

_ _

_ _

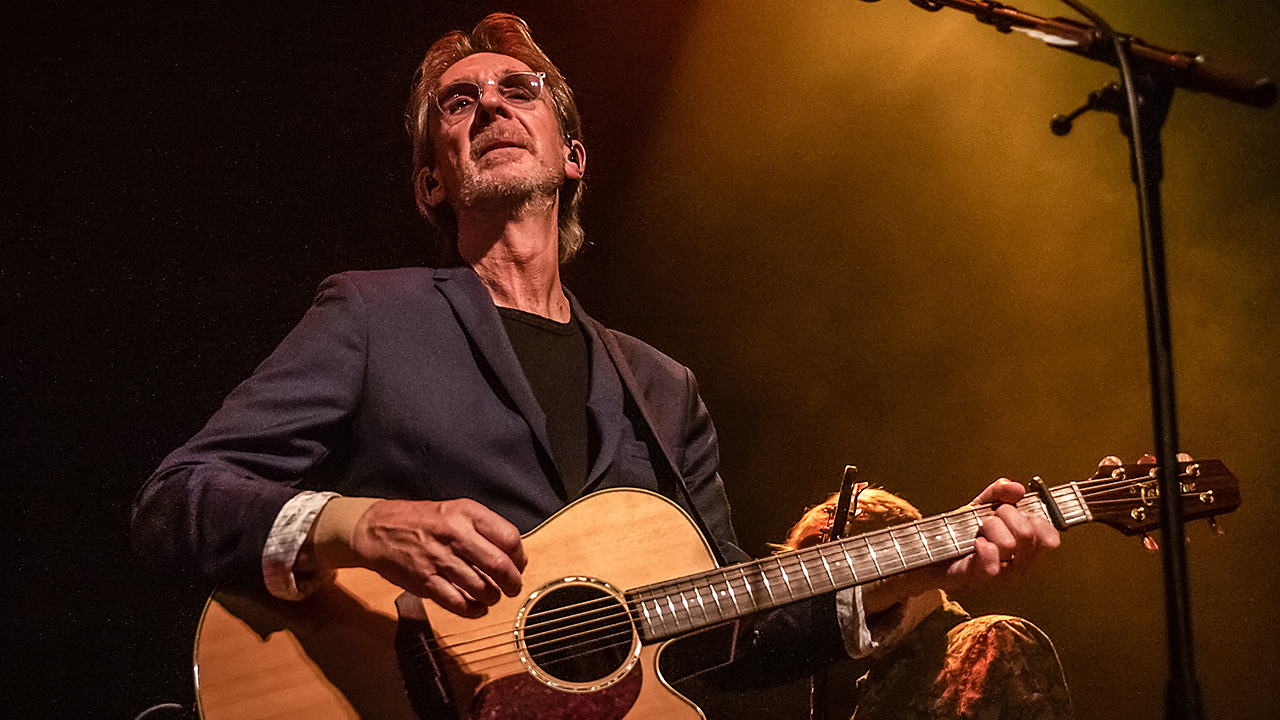

4. THE PUNK: CHUCK RAGAN

Living Outside The Machine

The revelation that an acoustic guitar could be just as impactful as a distorted electric guitar was rather forced upon Chuck Ragan. Ahead of his 12th birthday, the music-obsessed youngster begged his parents for an electric guitar and amplifier, and was duly granted his wish – for one whole day.

“The next day I came home and there was an acoustic guitar lying up against my bed instead,” the Florida-born singer-songwriter recalls with a raspy laugh. “I suppose you’d say my parents were supportive, but selective.”

By his own admission, the young Chuck Ragan was “a little bastard” to his parents, “a little rebel, causing havoc whenever I could.” Exasperated, Dave and Geraldine Ragan (a professional golfer and southern Baptist missionary/gospel singer, respectively) checked their teenager into a Gainesville ‘treatment facility’, a correctional institution for problem kids and young offenders. Each day for the next three years Chuck was required to keep a ‘Moral Inventory’, a daily journal reflecting upon his personal issues and his thoughts on the world beyond. When he was discharged from the facility at the age of 17, friends on the Gainesville punk rock scene encouraged Ragan to keep writing, but to marry his thoughts to music.

“I began to realise that music could be a release,” he says, “a tool to help us understand ourselves and to better ourselves and our surroundings. I never thought it could become a career.”

In truth, music has provided Ragan with not one but two careers, his role as frontman of hard-touring melodic punk band Hot Water Music being increasingly eclipsed by his emergence as a singer-songwriter of note. For Ragan, life as an acoustic troubadour represents liberation from the music industry machine – “life on the punk rock underground can be a grind, and at points I needed to take a step back and re-evaluate why I was playing music. I needed to love it again” – a notion he realised was shared by friends and acquaintances in the punk community. Since 2008 Ragan has been the lynchpin of the Revival Tour, a back-to-basics, freewheeling acoustic revue, inspired in part by his religious upbringing, which has seen artists such as Cory Branan, Brian Fallon (The Gaslight Anthem), Dave Hause (The Loved Ones) and England’s Frank Turner sharing stages across the US and Europe.

“It’s a very old way of sharing music. It’s how families and communities always shared music,” Ragan says simply of the Revue. “It’s about coming together and uniting everyone in that space. I think it makes for an incredibly interesting show, not only for the show-goers but also because it really recharges the batteries of those of us who’ve done this for years.”

The approach seems to be working for Ragan. Till Midnight, the 39-year-old’s fourth studio album, is his most eloquent and mature record yet; a folk and bluegrass-inspired slice of rootsy Americana ruminating upon lost innocence, hard times and lives lived in quiet regret. That the album is streaming for free online is both a reflection on the realities of the modern music industry, and also of Ragan’s life-long belief that sharing music and ideas is more important than having commercial success with it.

“When media interest in this ‘movement’ fades, some of us will continue doing what we’ve done for the past twenty-five years, whether people are listening to it or not,” he says. “Whether we’re playing on our front porch to a hundred and twenty people or playing the main stage of a festival. Some of us are in this for life.”

Till Midnight is out now on SideOneDummy.