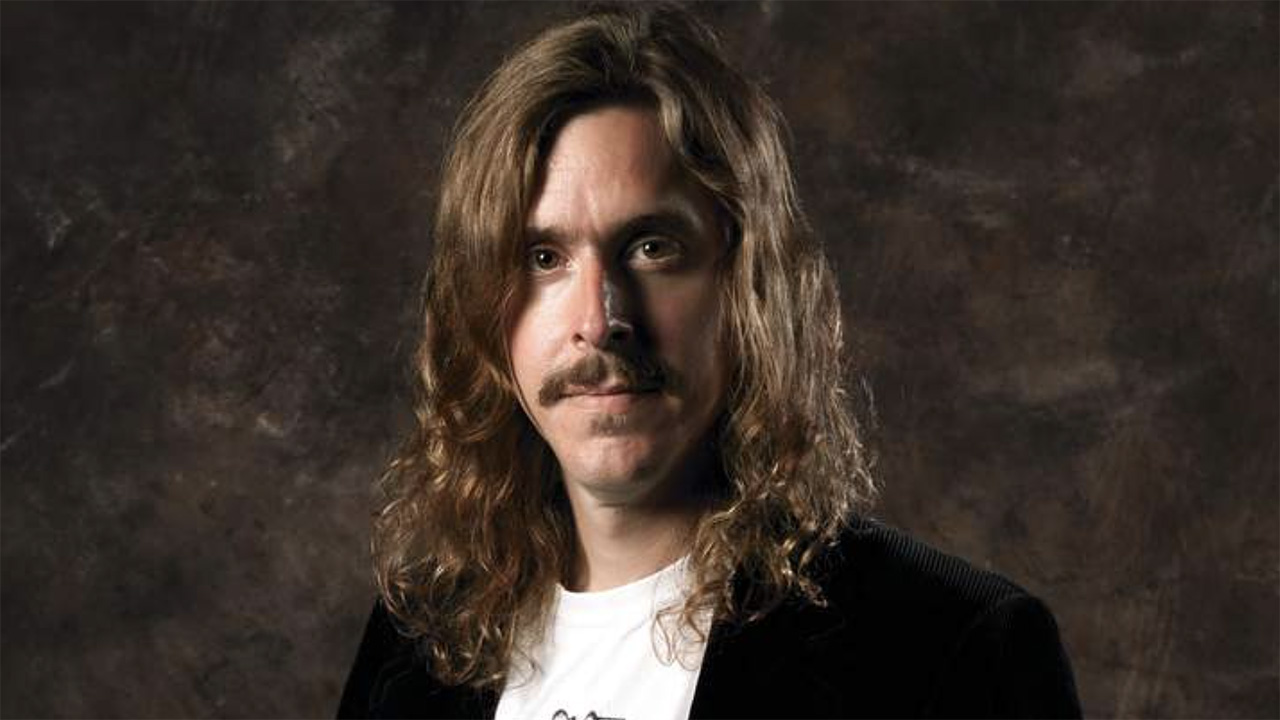

“When it comes to many of the classics, I don’t even know what they’re about!” How Mikael Åkerfeldt’s policy of not taking advice led Opeth to Pale Communion

Inspired by sharing records with Steven Wilson, he took a more melodic approach, added a vague title that just sounded cool, and forged them into a “journey through life that starts pretty good and ends shit”

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

As with earlier outings, dark confessionals, catastrophe, death and despair all fed into Opeth’s 2014 album Pale Communion. Yet with melodic hooks and David Crosby-inspired harmonies, it sounded like nothing they'd done before. Band Leader Mikael Åkerfeldt told Prog about the making of their 11th record just before its release.

Mikael Åkerfeldt can’t recall who said it, but there’s a quote that continues to inspire him: ‘A real musician doesn’t take advice.’

“I’ve always liked that,” the Opeth leader tells Prog down the line from his home on the Swedish archipelago. “What that says to me is that if you consider yourself a musician, it has to all come from within. All music genres are saturated with groups copying the latest big fucking band, so it’s important to remember that the word ‘progressive’ should say it all.”

It’s an issue he feels is particularly vital for metal and prog bands. And, considering they’ve often combined the best of both worlds over their quarter-century lifespan, it’s one that’s very pertinent when it comes to Opeth.

“It doesn’t mean that you should copy Genesis or King Crimson and think of yourself as a progressive band,” he continues. “Because for me, it’s not a genre – it’s the true meaning of the word. Progressive music is something that pushes things forward. That’s why today I really value music that I can listen to without finding obvious references for it. That’s what makes me sit up straight and go, ‘OK, what’s happening here?’ There are probably shitloads of people out there who just want to listen to a contemporary version of Genesis – my personal view is different.”

It’s a view that’s served him well thus far. Since joining the embryonic version of Opeth in 1990, then taking over as frontman and creative axis after the departure of founder member David Isberg two years later, Åkerfeldt has produced a body of work driven by a restless disregard for conventional boundaries.

Calling them a progressive death metal band even sounds reductive. With 1995 debut Orchid, they announced themselves as purveyors of a new kind of Scando-metal, fluctuating between grunting vocals and deft acoustic interludes. These were epic songs freighted with both anguish and antipathy; songs as beautiful as they were brutal.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Opeth’s trail has now led to their 11th studio album, Pale Communion. If 2011’s predecessor, Heritage, signalled a forward leap by way of a more open collusion of prog, folk and heavy rock – marked by knotty riffs, sparkling instrumental runs, itchy time signatures and growl-free vocals – this new one is another major shift.

It’s more cohesive than Heritage, for starters. And although it’s certainly no less complex, there’s a discernible emphasis on vocal harmonies and a more pastoral appropriation of the doomier end of folk music. As with Heritage, there are ringing echoes of 2003’s Damnation (the black sheep in the Opeth fold) in Åkerfeldt’s wholesale reliance on clean vocals. Above all, it’s perhaps their most organic album to date.

“We wanted to sound like a band of humans,” Åkerfeldt states. “I think we got caught up in new technology for a couple of records, where you could basically fix everything in the studio. But now we’ve left it sounding more natural, as opposed to having something more mechanical, with the robot-y sound that’s popular in metal today. We recorded the album at Rockfield Studios and decided that if you go in there, you should just put all your trust in yourself, rather than the engineer.”

Heritage was all over the place – that’s the stuff I like – but Pale Communion has more hooks

This, it transpires, is a key detail. While Åkerfeldt says he has no regrets over the exacting rigour of previous recordings, he does admit that they deliberately steered away from making everything ideal on Pale Communion: “In the past we’d cut various takes together to make a perfect version of each individual song. But with this one we mostly did one or two takes. Once we had the sound, we just went for it in the studio. And sometimes if I fucked up while I was playing and no one noticed, I just continued like nothing happened.”

Åkerfeldt cites one of his favourite albums, Judas Priest’s 1976 opus Sad Wings Of Destiny, as a major signpost. “That one was also recorded at Rockfield and there are mistakes in it. There are a couple of things on that record that are ‘untight’ – but that’s one of the reasons why I love it. It has a human quality to it.”

The whole album was cut in “10 days or so, like an old-school recording.” And while there are familiar spores of classic Opeth in the heavier, guitar-ripping tunes like Cusp Of Eternity and Voice Of Treason, the band’s love of pure melody is a more striking element.

“I only got some idea of what I wanted to do after I wrote the first song, which was Faith In Others,” Åkerfeldt explains. “The vocals carried the melody; and I figured that even if we have a lot of disharmonic stuff happening in our music, the melodic sense has always been there.

"I guess I wanted to take that to the next level. Heritage was all over the place and schizophrenic – and that’s the stuff I like – but Pale Communion definitely has more hooks. I think these songs are easier to understand than the ones on Heritage.”

As with its forerunner, the record was produced by Åkerfeldt himself and mixed by long-time ally Steven Wilson. The pair’s creative partnership has blossomed in recent years, culminating in 2012’s more esoteric side project, Storm Corrosion, and its self-titled album.

David Coverdale, Paul Rodgers, Ronnie James Dio – that’s how I want to sound. I can’t, but I’m trying

With both men being rabid collectors of vinyl, it was only natural that each would introduce the other to music they hadn’t heard before. If Pale Communion standouts like River and Elysian Woes carry a distinct tang of CSNY, there’s a reason for that.

“David Crosby’s If I Could Only Remember My Name [1971] was introduced to me by Steven a few years ago,” says Åkerfeldt. “And then I went into the whole Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young territory, which I hadn’t done before. Being a death metal kid growing up, that was old man’s rock. It was out of bounds;

I wasn’t interested in that stuff. But hearing Crosby’s solo record got me into his way of writing vocal harmonies. Actually, the original plan was to make a record with only vocal harmonies – but that didn’t happen.”

This fresh appreciation of vocalese may appear somewhat odd for a man who once professed to disliking his own voice so much that he would often try to bury it deep in the mix. Åkerfeldt is still modest about his talents in this regard, though he does admit: “I’m more confident now. Even though I’ve been the singer in this band for nearly 25 years, I never really saw myself as one.

“I guess I have aspirations that go higher than my ability. My favourite singers are David Coverdale, Paul Rodgers, Ronnie James Dio – those kind of guys. That’s how I want to sound. Obviously I can’t, but I’m trying.

“So with this record, I thought I shouldn’t be afraid of pushing it and delivering the vocals with the emotion they’re supposed to have. There was a point where I was only singing death metal vocals and it was so much easier for me. But I took that to a level where I felt like I wasn’t really creating anything new. So now I’m just concentrating on the clean vocals. Maybe that will make listeners feel a little more uncomfortable on Pale Communion, but I think it’s my best vocal performance on record so far.”

I was writing about stuff that wasn’t necessarily true – I was just imagining the worst that could happen

While all this may sound a little disarming to diehard Opeth fanciers, some things are unchanged. Lyrically, Åkerfeldt still remains the master of existential doom, pouring his anxieties into the new songs. The intricate, ten-minute Moon Above, Sun Below, for example, sounds like the soundtrack to one man’s journey through an earthly prison. Its proggy passages, rapturous at times, convey a tale of a wretched soul trying to escape a ‘forest of flesh.’

And while River finds Opeth in truly stately form, even flirting at the fringes of 70s AM rock, its message is overridingly bleak. ‘Because when you have no one,’ sings Åkerfeldt at his most despairing, ‘No one will care.’

Such intimations, he reflects, “are nothing new for us.” Even the album title dips its toe into the dark stuff: “I wanted to sum up the lyrics, because the album is some kind of confessional. I felt like Pale Communion just worked. And it sounds cool. It was also a reference to death, like a pale companion.”

But there’s only so much premeditated angst to go about. Åkerfeldt is refreshingly candid: “When it comes to many of the songs in the Opeth camp, the so-called ‘classics,’ I don’t even know what they’re about!” he laughs. “It’s just bollocks, really. I could still tell you what most of the songs on Heritage or Watershed [2008] are about, but with the older ones I often can’t remember. I usually find myself writing in the heat of the moment and only afterwards do I try to make out what it actually means.

“But the new songs are more personal in the sense that I’m writing about immediate things that are happening around me. Many of them are about my private life, which has been troubled, off and on. And I have a tendency, when I start feeling down, to foresee things as becoming catastrophic. My mind takes on a life of its own and the tiniest thing can escalate into a massive problem. There’s probably some term for this.

“With these lyrics I found that I was writing about stuff that wasn’t necessarily true – I was just imagining the worst that could happen. And it bounces between pleading and desperation, like on the song River, to ‘Fuck it, I can make it on my own.’ It’s all a bit schizophrenic.”

The main thing is that I feel like I’m still learning

Given a decent tailwind, Pale Communion could be a very big album for Opeth. Their current line-up – Åkerfeldt, guitarist Fredrik Åkesson, pianist Joakim Svalberg (who replaced Per Wiberg after Heritage in 2011), bass player Martín Méndez and drummer Martin Axenrot – seems to be both stable and highly capable.

And the signs are certainly good: Heritage recorded first-week sales of nearly 20,000 in the US, peaking at No.19 on the Billboard chart. In the UK it reached No.22, while also placing high throughout Europe and in Australia. In short, it was their most successful record to date. Sales were also spiked by a major tour of the States, where they shared top billing with Mastodon.

Another notable feature is Opeth’s presentation. Their album covers are often laden with symbolic images of the world they perceive. The burning theatre on Heritage, for instance, is supposed to represent the decline and failure of civilisation. Conceived by regular designer Travis Smith, Pale Communion depicts a trio of paintings on what looks like a dungeon wall, lit only by a solitary shaft of sunlight.

Each painting contains a Latin quote. The first one comes from Sweden’s 17th-century Lord High Chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna: “Don’t you know, my son, with how little wisdom the world is governed?” The other two are hardly filled with hope either.

“I knew from the get-go that I wanted Latin text on the cover,” Åkerfeldt says. “And the fact that one of the guys was Swedish was cool. The quotes were basically something that would fit together with each individual painting. The original idea was to have a triptych – they’re supposed to show a journey through life that starts pretty good and ends shit.”

He can’t help but allow himself a quiet chuckle at his own words; perhaps at the irony of it all. The eternal pessimist, presiding over a world that, on a wider scale, might finally be ready to open itself up to this band of his. “The main thing is that I feel like I’m still learning,” he says. “And that’s very important to me: to make myself feel like I’m actually progressing.”

Which is where we came in.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.