Ennio Morricone: The Outer Limits

He’s the visionary Italian composer who has created music for more than 500 film and television scores, from bloody crime dramas to devilish horror movies and spaghetti westerns.

His epic soundscapes have influenced Mogwai and Metallica. So now we ask: How prog is Ennio Morricone?

Popular cinema tends to make few concessions to prog rock when it comes to soundtracks. Ennio Morricone, however, is a glaring exception. In a career that’s spanned over six decades, the Italian composer has written over 500 original film and TV scores, among them The Mission, Once Upon A Time In America, Days Of Heaven, The Untouchables, Cinema Paradiso and Kill Bill.

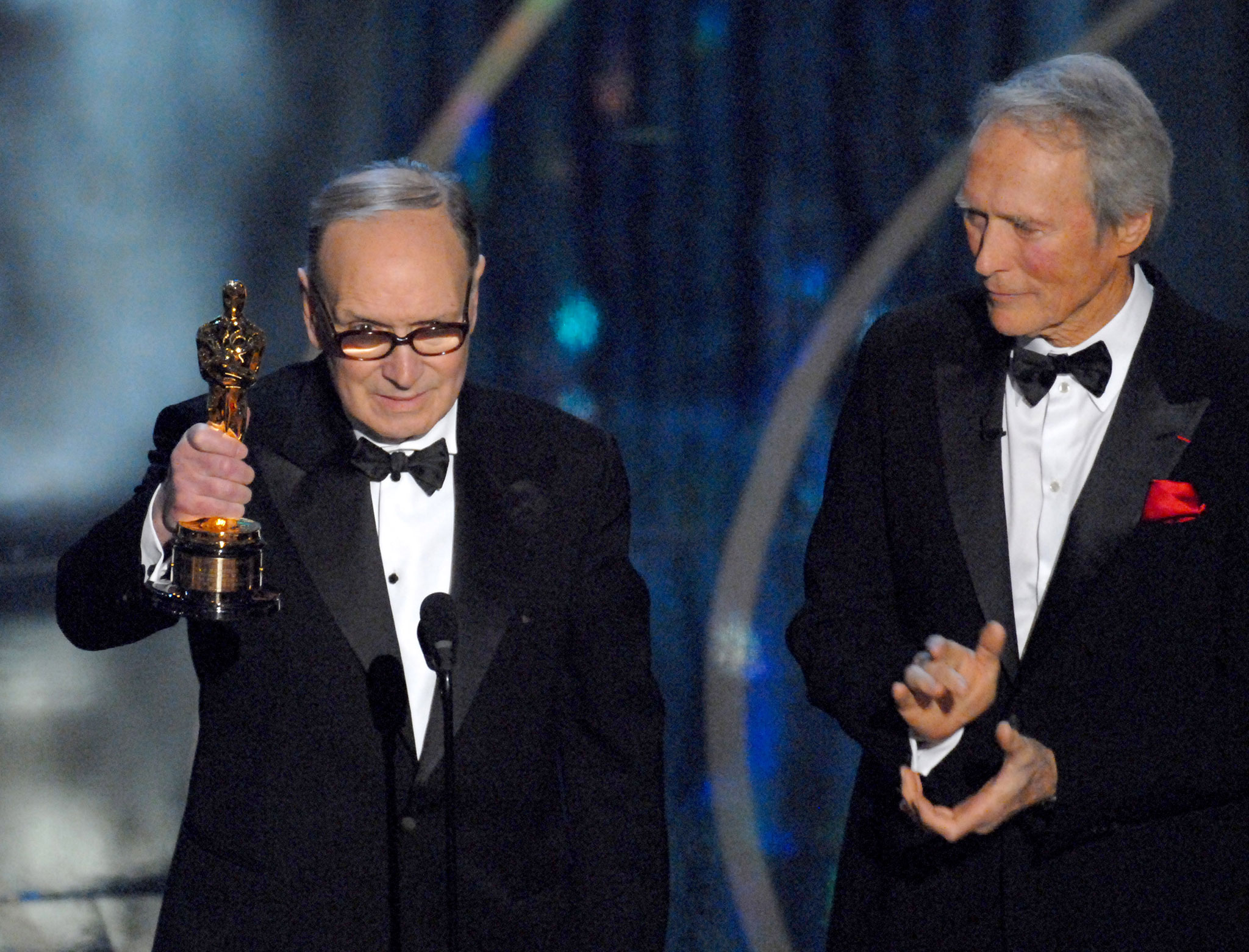

There’s his unforgettable work for director Sergio Leone on the trio of spaghetti westerns – A Fistful Of Dollars, For A Few Dollars More and The Good, The Bad And The Ugly in the mid-60s – that not only made actor Clint Eastwood’s name but also came to define the sound of an entire genre. In 2007 Morricone was awarded an honorary Oscar, presented by Eastwood, in recognition of his “magnificent and multi-faceted contributions to the art of film music”.

The one constant in all this is a keen sense of experimentation. An adventurer at heart, Morricone’s art is founded on a love of avant-garde forms, classical composition, jazz and chamber music. Even his Leone soundtracks – an audio vérité of whips, gunshots, mariachi trumpets and wordless voices – were decidedly off-script when it came to conventional western scores.

“Morricone is very appealing to fans of prog rock,” says sax/flute player and composer Theo Travis, who has worked with Gong and Robert Fripp. “His music is hugely progressive and there’s so much musical ambition, as well as development of themes, that change and reappear in a slightly altered way. Plus there’s wonderful orchestration, bringing all sorts of musical forces together for the sake of the musical whole. The vastness of scale makes most symphonic prog sound like your local pub band.”

Morricone himself, or Il Maestro as he prefers to be called, is in good spirits – “Bonjourno! Bonjourno!” – when Prog puts in an early morning call to his apartment in Rome.

The city where he was born has served as home for the entirety of his 86 years, despite numerous invitations to live elsewhere, most notably from studio bigwigs in Hollywood. This resistance to the lure of Tinseltown is emblematic of an ongoing need for creative freedom.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I live in a wonderful house and I feel better in Rome,” says the non-English-speaking Morricone, through his interpreter. “[Italian film producer] Dino De Laurentiis once offered me a wonderful villa for free in LA, but I was afraid that I was going to pay the price when he was paying for the music I composed. That’s why I resisted, I knew it was a very dangerous offer.”

Ennio Morricone began his career as a trumpet player, studying composition and choral music at the National Academy of Santa Cecilia. So prodigious was he that he completed the four-year course in just six months.

His first classical works and arrangements came when he was still in his teens, after which he juggled ‘serious’ pieces with light orchestra commissions for popular Italian TV service, RAI. By the late 50s Morricone had become a studio arranger at RCA, overseeing sessions for big stars such as Mario Lanza and Rita Pavone. Though it was 1961’s The Fascist, the first of several scores for director Luciano Salce, that set him off in the world of film.

Inspired by Dimitri Tiomkin’s work on Rio Bravo, Morricone’s former school classmate Sergio Leone hired him to make a unique soundscape for A Fistful Of Dollars in 1964. The idea, he said, was to create music that would both punctuate and heighten the drama on screen, as well as mirror the film’s sense of dust-blown isolation.

Both men found an instant rapport that sustained them throughout the ‘Dollars Trilogy’ and beyond. “I usually work with directors and filmmakers with whom I have a good relationship,” Morricone explains of his working methods. “So it starts from that point. I don’t work with a director that I don’t feel at ease with.

“If I compose a score for a director and the relationship isn’t good, then there won’t be a second time. With Sergio Leone I didn’t have any disagreements. There has to be a kind of trust in the relationship, because the director is entrusting you with the composition of his music score.”

If the music for 1964’s A Fistful Of Dollars was avant-garde by cowboy western standards, it was nothing compared to Morricone’s other project of the time. The same year saw him co-found Gruppo di Improvvisazione di Nuova Consonanza (better known as Il Gruppo), a revolving musical collective whose remit was the exploration of “anti-musical systems and noise techniques”. For Morricone and friends, this involved spontaneous works that combined free jazz and musique concrète to create what they termed “New Consonance”. With Il Maestro as a core player, this was prog on a vast musical canvas.

Morricone explains that all this came about during a period of crisis in contemporary music. “There was a big festival in Darmstadt [Germany],” he says, “and I noticed that the contemporary musicians wrote in a quite complicated way, even from a classical point of view. They wrote music that was very difficult to interpret or understand. So when it came time for us to perform at the festival we ended up doing some improvisation, because the music was so difficult to read. What we did wasn’t aligned with what was usually heard and played at that time.”

Il Gruppo went on to release seven albums over the next 12 years. One of them, 1970’s The Feed-back (under the name The Group) has since become a prized artefact among hip-hop samplers, by way of its liberal spread of funk, open-ended jazz and avant-classical figures. “We used the instruments in quite a different way to begin with,” adds Morricone. “The sounds were almost unrecognisable, because we really abused those instruments. It was totally different from what people usually listened to.”

Il Gruppo flourished until 1980, a year after Morricone received an Oscar nomination (the first of five) for Terrence Malick’s Days Of Heaven.

“Il Gruppo decided to split up when we realised our presence was useless,” he explains. “Because by then composers were writing and playing music that was mostly traditional. We thought that maybe our role was finished.”

Some of Morricone’s most striking creations were made to accompany the horror films of Dario Argento in the late 60s and 70s. The soundtrack to The Cat o’ Nine Tails, for instance, is a masterclass in claustrophobia. The music for The Bird With The Crystal Plumage, meanwhile, is every bit as disturbing as the movie itself; shards of avant-noise shivering through its spine. The voyeuristic sense of dread is accentuated further by the eerie moans of Edda Dell’Orso, another frequent Morricone collaborator.

For Scottish post-rockers Mogwai, Morricone’s horror phase was particularly inspiring, especially leading into the recording of their most recent album, 2014’s Rave Tapes.

“The proggiest songs we like are things like Morricone’s Magic And Ecstasy,” offers Mogwai leader Stuart Braithwaite. “It’s the theme from Exorcist II [1977]. The film isn’t great, but the soundtrack is amazing.”

When it comes to his big-budget scores of the 80s, perhaps the most impressive are the ravishing orchestral soundtracks to _Once Upon A Time In America (1984) _and The Mission (1986). The former was his final film with Leone, who died of a heart attack at the end of the decade. As for The Mission, Morricone lets Prog in on a secret.

“This is a revelation for you,” he says. “They actually wanted another composer. The Italian producer [Fernando] Ghia had asked me to write the music. So he invited me to London to watch a screening of The Mission. Afterwards I said no, because the film was already so beautiful on its own, without any music. In the end he and [Ghia’s co-producer] David Puttnam convinced me that music was needed.

“I only discovered what really happened much later, but Puttnam wanted Leonard Bernstein instead of me,” he reveals. “Ghia opposed that, because he wanted to have Il Maestro. So they found a solution: if Leonard Bernstein accepted, he would write the music. But they never found him. So I composed everything for The Mission. I wasn’t aware of any of that, otherwise I would have refused to work in that way. But I’m very satisfied for having done it, because I would have regretted not composing the music for that film.”

The Mission, an epic story of Jesuit missionaries in the Paraguayan jungle, without Morricone’s sumptuous music? You really couldn’t imagine it any other way. The soundtrack went on to become one of the biggest-selling movie scores in history, shifting over three million copies worldwide.

Morricone’s appeal endures. The 2007 tribute album, We All Love Ennio Morricone, featured artists as diverse as Bruce Springsteen, Celine Dion, Roger Waters and Metallica, who covered Ecstasy Of Gold, their introductory stage music since 1983.

Meanwhile, Il Maestro’s work ethic remains as healthy as ever, though his body sometimes reminds him that he’s getting on a bit. Last year found him providing soundtracks for Tornatore: Leningrad and The Canterville Ghost, in between touring with his orchestra.

A spinal injury cut short the last endeavour, but after resting up for the best part of 2014 he’s currently back on the road, stopping off at 20 European cities in the final leg of his My Life in Music world tour. Morricone’s currently writing music for a film set during the German occupation of France in World War II.

Remarkably, given all that he’s achieved, he still admits to certain insecurities. “I always have doubts,” he says. “In any creative profession, you must have some doubts. Maybe it helps your growth, maybe it helps you mature and improve what you do. It’s a healthy thing.”

For Theo Travis, Morricone is one of the greatest film composers of all time. “The Good, The Bad And The Ugly is probably the most instantly recognisable motif in all film music,” he says. “But when you hear the original score it’s still hugely effective. Cinema Paradiso works so well as a standalone piece of music. I’ve heard it performed by Pat Metheny, Charlie Haden and also Yo-Yo Ma. But his soundtrack to Once Upon A Time In America is perhaps the greatest of all. I think it’s cool that Morricone started out as a trumpet player and was in the avant-garde free jazz scene. He’s an inspirational musician and composer, with no boundaries.”

See www.enniomorricone.org for more information.

YOUR SHOUT!

_Good? Bad? Ugly? But just how prog is Mr. Morricone? _

“He had a flute on My Name Is Nobody – also used in Nighty Night!”

Barbara Kirk

_

_

“Much. He’s one of the greatest.”

Danilo

_

_

“The theme from The Good, The Bad And The Ugly tells you…”

Hoppy Hopster

“Seriously?”

Thomas Gitpoloulos

_

_

“120%”

Marco Libertucci

_

_

“In my honest opinion more electronica, but that doesn’t detract from a progressive tag.”

Daniel Black

_

_

“Not at all.”

Lars Helge Rasch

_

_

“As so many prog records are described as soundtracks for imaginary films for your mind, then virtually any soundtrack writer can be considered prog.”

Chris Bembridge

_

_

“If you go beyond the usual western stuff there’s plenty of music in his 60s/70s work that would appeal to prog fans.”

Steven Pieper

_

_

“I think he was a very progressive composer.”

Cranium Pie

_

_

“Him and Esquive. Progressive classical – a new category!”

Christopher Buist

_

_

“100%. He pulled guitar and orchestra together, created and took them both to new places, and it rocked. The dollars soundtracks were groundbreaking. Prog in a nutshell.”

Neil Reeves

_

_

“Ennio Morricone is everything.”

Domenico Abbate

_

_

“Just NO!!!”

Vernon Allen

_

_

“OFFS! You really are clutching at straws now, aren’t you?”

Giles Kendrick

_

_

“Who?”

Auden Engebretson

_

_

“0%”

Patrick van den Splinter

“Ecstacy Of Gold? He’s metal!”

Timothy Breen

“He’s broken the rules over and over and reinvented the soundtrack time and time again, very progressive, so yes, I’d like an article on him.”

Mark McCormac

_

_

“Makes a change from yet another article about Steven Wilson.”

John Sayer

_

_

“Oh please. Kylie’s more prog than him!”

Robert Humperdick Hughes

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.