The Life and Hard Times of Big Country and Stuart Adamson

The surviving members of Big Country on their rise, fall, and subsequent rise – and the suicide of Stuart Adamson

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

'People say I’m the life of the party/Cos I tell a joke or two/Although I might be laughing/Loud and hearty/Deep inside I’m blue.’

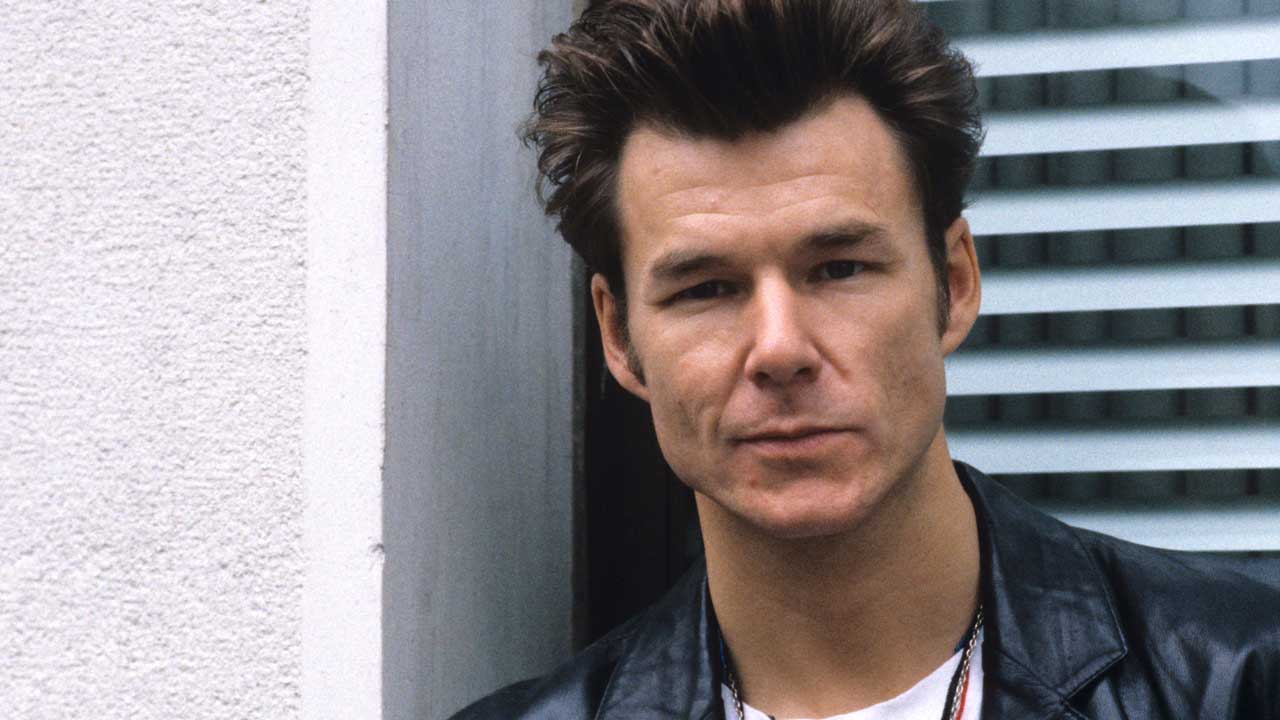

The words are from Smokey Robinson’s The Tracks Of My Tears – some of the lyrics that doubtless inspired Bob Dylan to call Robinson “America’s greatest poet” – and Stuart Adamson sang them on the b-side of Big Country’s fourth single, Chance. Listened to today they seem to have a greater resonance. The grief that followed Adamson’s suicide in December 2001 was matched only by an equal outpouring of disbelief and confusion. Adamson was successful, handsome, charismatic, talented. He made music that was inspirational, compassionate and uplifting. Onstage he was the life of the party, loud and hearty. But deep inside?

It sounds stupid, Classic Rock tells drummer Mark Brzezicki, but you don’t think that even then he was trying to tell us something?

Article continues belowBrzezicki doesn’t think it’s stupid: “As a drummer,” he says, “I never really paid attention to the lyrics. I paid attention to the bass lines, I paid attention to the different dynamic, to the way the strumming was happening, everything to do with rhythms – and the voice was a rhythm to me… Only in hindsight I’ve started looking at lyrics and I’m starting to go, ‘Hang on a minute – the writing’s there. This guy was saying it all along’. Or was he? I don’t know.”

In some ways, the Big Country story, like most rock stories, begins in the 60s. The best of times and the worst of times. Civil unrest and civil liberties. NASA and LSD. Men on the moon and a younger generation exploring inner space. Dylan and Keef and Jimi.

Future BC manager Ian Grant was an agitator and troublemaker. Grant fell into management after promoting and staging illegal ‘happenings’ around his home town of Worthing. “We did these nights on the Cissbury Ring ruins. You’d buy a ticket, and the acid tab would be stuck underneath a postage stamp on the ticket. Brian James [later of the Damned]’s band played a couple of times, the Pink Fairies came down once, Michael Chapman.

“The thing was, it was so remote, if the cops came you’d see them, cos they had to come up the hill. The first time they came they brought dogs, ten of them. We stashed everything. We were all tripping, hanging upside down from the trees like bats. So these cops come with torches and don’t know what to do: ‘Get down from that tree’ [mimics uncertain cop voice] ‘…or we’ll arrest you’.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Grant went from that to gravitating, like so many of the supposedly redundant ‘hippy’ generation, towards the trouble-makers of punk, managing The Stranglers, among others. It was JJ Burnell of The Stranglers in fact who first turned Grant on to the Skids, having witnessed them in Falkirk while on tour. Grant was bringing Scottish acts like Penetration and the Rezillos down to London and “[JJ] said, ‘Would you bring down the Skids? I’ve found this band that I want to produce’.”

The Skids got a Peel Session and a deal with Virgin out of the trip. Virgin put the late Dave Batchelor, producer of many Sensational Alex Harvey Band albums, behind the desk, but Burnell didn’t hold a grudge: the Stranglers later took the Skids on tour with them and by the time of the Skids’ third album, The Absolute Game, Grant was managing them alongside Alan Edwards (now head of famous PR firm The Outside Organisation).

Skids guitarist Stuart Adamson was already honing the sound that would find full expression in Big Country. Inspired by the energy of punk, his playing style owed less to the power chords of Johnny Ramone than it did the mercurial lead lines of Be Bop Deluxe’s Bill Nelson (who produced the Skids’ second album), the jerky rhythms of Nils Lofgren, or the steely solos of Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner (Alice Cooper, Lou Reed). Even lyrically, the Skids had established a blueprint that would be echoed in Big Country: rousing songs of arms and adventure – Boy’s Own stories with a new wave twist.

“I think [we were] trying to understand masculinity in a way,” says former Skids frontman Richard Jobson. “And that military imagery is so potent. If you look at the sleeves of Masquerade and Charade [pictures of the battle of Culloden and uniformed men playing cards with a gun on the table, respectively], thematically, they’re about masculine grace. If you were really going to analyse all the work, I think you’ll find that’s at the root of it all – finding some kind of grace in the whole process of being a man. And not being ashamed of that.”

But by 1980 Adamson wanted to be his own man again. He had formed the Skids and was the nominal leader but Jobson – a 17 year-old during the first album – had grown to be a strong-willed and principled artist himself. By The Absolute Game, Jobbo had formed a writing partnership with the band’s new bassist, Russell Webb, and Adamson wanted to start again with a project where he was in charge.

Hooking up with guitarist and long-time friend Bruce Watson, an early Big Country line-up also featured Peter Wishart, later of Gaelic rockers Runrig and now an SNP MP for Perth, on keyboards. “We could have went the other way [musically],” says Bruce. “Stuart and I were fucking about with synthesisers on ironing boards. It was at that time when synths were in: it was all Human League stuff, and I do love all of that stuff…”

Adamson had something more traditional thing in mind. As he once said: “Music used to be a thing where working people got together on a Saturday night and played some songs. Someone’d play the guitar or the fiddle or an accordion. No bastard’d played the synthesiser.”

Music used to be a thing where working people got together on a Saturday night and played some songs. Someone’d play the guitar or the fiddle or an accordion. No bastard’d played the synthesiser.

Stuart Adamson

An early version of the band cut demos with Rick Buckler from The Jam on drums and shopped them around the major labels. “And everyone passed,” says Grant. “I think the songs were Heart And Soul and Inwards. Heart And Soul was the song at one point – ‘This is what we’ll get a deal with’ – later it didn’t become anything other than a B-side. Polydor passed, Arista passed, CBS passed. I still have all the letters.”

A support slot with Alice Cooper went disastrously too, the band’s half-baked sound grating on an audience looking for glam-metal thrills. By the second night of the tour, Cooper’s tour manager was on the phone to Grant: “Your band’s off the bill, no arguing”.

Faced with all this negativity, Grant persuaded Adamson that the band needed a shake up. Out went keyboard player Wishart, his bass player brother Alan and drummer Clive Parker, and in came bassist Tony Butler and drummer Mark Brzezicki. The two men had spent the last few years building a reputation as the ‘Sly and Robbie of Soho’ and had just finished recording Pete Townshend’s Empty Glass album.

Demos produced by John Brand (later the manager of the Stereophonics) convinced A&R man Chris Briggs to sign them to Phonogram, and attracted Empty Glass producer Chris Thomas. With a CV that included Dark Side Of The Moon and Never Mind The Bollocks, Thomas seemed the perfect choice – but the sessions failed to deliver. Thomas was jetting out to the Caribbean throughout the recordings to work on Elton John’s Jump Up album at the same time. A single, Harvest Home, was the only song salvaged – released in September 1982 it went to an inauspicious no.91 in the singles chart.

“And you know how record companies are,” says producer Steve Lillywhite. “Everyone’s very excited and when it doesn’t work out suddenly it’s [sniffy voice] ‘Oh, I’m not sure about that’. All of a sudden it had gotten a bit weird with Big Country. Because one of the best producers in the world had not delivered. It sounded flat and uninteresting.”

Lillywhite, the man behind the first three U2 albums, was the final link in the chain. “It was the second wave of punk,” says Lillywhite. “I’d had some success with Siouxsie And The Banshees, the Psychedelic Furs. But to me punk rock was a springboard to other things. I loved it as an attitude but as an art form it was very limited. I was never into the UK Subs’ form of punk. For me it was art. XTC and even the Psychedelic Furs with all their chaos – we considered it art, not just noise.”

Lillywhite had just finished recording U2’s breakthrough album, War. (In 1983, he would record War, The Crossing and Simple Minds’ last great album Sparkle In The Rain in that order – three albums that would define the ‘Big Music’ of the 80s.

Reminded of that today, even he’s surprised: “Wow. I was good in those days…”) Initially contracted to just do a single, the sessions for Fields Of Fire produced not only that classic song, but gave birth to the Big Country sound and inspired a new bout of songwriting from Adamson.

“We gave them this great spirited, uplifting feeling,” says Lillywhite. “Chris Thomas’s recordings were flat and uninteresting and we managed to get something exciting going – and from that Stuart went off and wrote In A Big Country. I remember playing Bono the demo of In A Big Country, I was so absolutely knocked out by it. I felt very honoured to have inspired that.”

The team suddenly clicked: Grant, Lillywhite and Briggs inspiring and delighting in the four musicians, the perfect mix of muso experience and punk energy.

Grant: “What made it so special? It’s just a certain chemistry. You can’t quantify it – it either comes or it doesn’t. The passion and the motivation of everyone – some of it rubs off. Like you put a dry log next to an ember and it catches fire – it’s the same thing.”

Tony Butler, a session musician tired of being a gun for hire, had found the band he was looking for: “I thought what Bruce and Stuart were doing guitar-wise was immense. And it was lyrical, it was melodic, it was powerful – it was just lovely. I’ve got Scottish roots and it really kind of erupted from me when I first heard these guys playing…”

Bruce and Stuart had already laid down some internal rules. “We made a conscious effort not to play any blues notes,” says Watson. “We wouldn’t bend strings. [Mimics himself as a young punk] ‘For the first few albums, we’re not bending notes, right, because that’s just fucking pish!’ Cos that way you get into blues territory and we didn’t wanna go anywhere near the blues rock thing. So we just played melodies.

“There was no guitar solos in the first couple of albums: it’s just guitar melodies, and it’s usually just a scale, sometimes with a harmony, sometimes with a double track – sometimes we used harmonisers and a bit of delay and reverb to make it sound sweet. And that’s why people say it sounds like the bagpipes. There’s all that reverb and sometimes drone strings as well – but Jimmy Page had been doing that for years.”

The guitar playing gave the bass a unique role. “The bass was the third guitar basically,” says Butler. “It kinda held down notes now and again but it joined in melodies and counter points and stuff which is what really interested me in playing with the band cos it explored stuff like that and there weren’t lot of people that I knew that who were doing that on bass, really.”

And then there were the drums. Mark Brzezicki was inspired by drumming’s unique stylists – John Bonham, Mitch Mitchell, Phil Collins (“I went to see Boxer at the Roundhouse in 1975/76, when I’d just started playing. The support band blew my socks off – Brand X, with Phil Collins playing the drums. I’d liked Genesis anyway, but when I saw Phil come out in his dungarees, with a big beard and this monstrously brilliant drum kit…”) – and he immediately saw an opportunity to do something unique.

Coming in literally days after recording with Pete Townshend, Brzezicki was amazed at how Scottish the music was. In his head, he started to think: “It’s got kind of a marching feel. Now, nobody’s done marching stuff…”

A fan of Steve Gadd’s drumming, particularly the military style he used for Paul Simon’s 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover, Brzezicki began to blend it with his own style, encouraged in the studio by Lillywhite. Where other producers would remove much of the natural rhythm and grace notes produced by a drummer, Lillywhite and Brzezicki conspired to leave it in.

Brzezicki: “I said at the time, ‘It’s the sum of the parts, like a machine: a machine’s running and you hear a squeak? Leave the squeak in: it’s in time, it’s all part of the rumble – I want it all in’. Lillywhite loves that, so it was like, ‘Brilliant – let’s mic you up close in a big room and get a huge big drum sound because it’s all got to be like a machine running…’”

If Brzezicki and Butler were seasoned pros by this time, Bruce Watson was new to the process. Nevertheless Lillywhite drew out his ideas. “I’m a young musician with my first proper studio session,” says Watson, “I’ve got these fucking mad ideas and I’m thinking, ‘He’ll never wanna try them’. But Steve was like: ‘I wanna hear them’.”

“There are two schools of record producers,” says Lillywhite. “One will look at a band and say, ‘Who’s the leader? Stuart: OK, I’ll go and really work with him because he is the creative talent’. Whereas I’ll go into an album and go, ‘Who is feeling insecure? Who do I need to bolster up?’ Bruce was so nervous. His hands used to shake like crazy in the studio. I try and inspire a sense of team work rather than divide and rule.”

It was a creative union that Watson would struggle to find again throughout the band’s career. “Later in life,” he says, “you’re doing different sessions with other producers and it’s just like: ‘This ain’t the same as working with Steve’. It was just fucking amazing. He’s a genius.”

At the heart of it all was Adamson, the punk rocker with the virtuoso talent. “He used to say, ‘Don’t call me a musician. I’m a songwriter, guitarist, singer, but muso – I don’t like that tag’,” says Brzezicki. “And yet actually he was a really good muso. Although he was playing punk, he still really knew how to play the guitar. Stuart was groundbreaking – he was making this stuff up. I think that’s it: we were allowed to make stuff up and, unlike any other situation I’ve been in, we were encouraged to do so. It was allowed to happen through Steve Lillywhite, but it happened before we even had a producer because Stuart embraced all originality. There were no rules – if it sounded good and fired us up that’s what went down.”

The results were explosive. The music of The Crossing was epic and inspirational, as big as the glens and as loud as a cavalry charge. It was rock music, but not the rock music of Led Zeppelin, AC/DC or Aerosmith. It was modern – with guitar tones and effects that you’d find on records by U2, The Cure and the Cocteau Twins – but also harmonised guitar parts that reminded you of Thin Lizzy and Wishbone Ash. Sometimes it sounded positively ancient: traditional, eternal. Its lyrics talked of mountainsides and ploughmen and harvests and the westerly winds sighing. Kid Creole and the Coconuts it wasn’t.

If the first three singles, Harvest Home, Fields Of Fire and In A Big Country had established the crowd-friendly skirling guitars, big beats and uplifting calls to arms, the album also had subtler depths to enjoy: Chance’s soulful social commentary (“a beautiful, depressive song,” says Lillywhite), the inter-weaving guitar lines of the eight-minute Porrohman (“sort of progressive rock,” admits the producer) building as skilfully as Stairway to Heaven before breaking into a Highland jig.

Stuart Adamson himself, writing for the sleevenotes for the CD reissue of The Crossing, put it perfectly: “The music I felt wasn’t like the music I had grown up hearing, or rather, not like any one of them. It was all of them jumbled up and drawn into something I could understand as mine. I found that I could play this music and connect the guitar directly into my heart. I found others who could make the same connection, who could see the music as well as play it.

“The sound made pictures. It spread out wide landscapes. Great dramas were played out under turbulent skies. There was romance and reality, truth and dare. People being people, no heroes, just you and me, like it always was.”

Released in July 1983, The Crossing went on to sell over two million copies worldwide.

“My first encounter with Stuart was a U2 show at the Hammersmith Palais,” says The Alarm’s Mike Peters. “Big Country were supporting and I had been invited on as a guest. In the weeks leading up to the show I’d taught U2 how to play Knocking On Heaven’s Door – we used to play it in our set and Bono would come on and sing it with us. At Hammersmith Bono introduced me to the stage and then he also invited Stuart Adamson up. Stuart was in the crowd, and he came over the heads of the crowd and over the barrier, and I helped pull him up and that was the first time I shook his hand. Bono introduced us then as being ‘the new breed’.”

The new breed had neither the aloofness of the old guard of rock stars, or the nihilism of the punks. The barrier between audience and band had broken down (however temporarily). After the Hammersmith show, Peters and Adamson stood signing autographs side by side.

“Stuart would always sign ‘With respect, Stuart Adamson’ and I thought that was fantastic,” says Peters. “It wasn’t ‘good luck’ – it was something deep. It was a very respectful way of doing it. It wasn’t like the autographs I’d got from bands. I went up to Johnny Rotten in 1976 and asked him what Anarchy In The UK meant and he told me ‘Fuck off!’ – and here was a guy signing it with respect…”

The bands were so finely attuned that The Alarm were working on their third album – to be called Steeltown – when they heard that it was also the title of Big Country’s next album. (The Alarm changed their album to Strength and the song Steeltown to Deeside.) For the recording of Steeltown, Big Country had relocated to ABBA’s Polar Studios in Stockholm. “Steve had to work abroad for tax purposes at the time cos he was doing everybody,” says Bruce Watson. “He suggested going to Polar Studios but digital [recording] was in its infancy and we were just having a lot of problems, just with the sound. The songs were there but it was just all technical.”

On its release in October 1984, Steeltown went straight in at number one, but its singles struggled to crack the top 20 and worldwide it sold only a fraction of The Crossing. A lyrically dark and sonically dense album, it lacked the dynamics and beauty of their debut and the stand-alone single, Wonderland, that had preceded it.

“There were no hits on it,” says Grant. “I hate that phrase, but there were no classics on it. I think it was rushed. No one had their eyes on the ball, and there were internal problems. Internal problems within the problems – husbands and wives, babies, Lillywhite getting married to Kirsty MacColl [the producer proposed to MacColl at a Big Country gig at the Glasgow Barrowlands, New Years Eve, 1983]. He was recording on an SSL desk for the first time and technically I wouldn’t have a problem with that, but I know it gave him a problem because he was experimenting.”

“We just went to town with the guitars and drums,” says Watson. “‘Let’s flood this album with as many overdubs as possible…’ Maybe Steve could have been a better referee and said, ‘Let’s just not bother with that…’ Steve’s 12” mixes were great because he would take stuff out and feature a bass, or another instrument, and it’s great, but with a 7” mix, everything’s condensed. Steeltown was like that.”

Adamson, for his part, backed his producer, saying shortly after the release: “Steve Lillywhite gets lots of shit but I think he did brilliantly. I think it’s one of the finest albums I’ve ever heard. I’ll not be small about it.”

“Steeltown is a bit dense and a bit muddy,” admits Lillywhite today. “But maybe we were trying to put too much on because maybe we trying to cover something up. Maybe Stuart’s writing had become more political and even if people are living in a steeltown with no work and everything, they wanna lose themselves. They don’t want to be told that their life is shit. Maybe they need the big dreams even more…”

For all the talk of Big Country’s uplifting side, the band had always been more than the plaid-shirted, bagpipe-guitar playing jolly Scotsmen the press had them pigeon-holed as. The Crossing was filled with hard luck stories and dark imagery (‘There is no beauty here friends/Just death and rank decay’; ‘The houses were burning, the flames gold and red/The people were running with eyes full of dread’; ‘The continents will fly apart/The oceans scream and never part’; ‘Our homes on fire/My wife has fled’) but the music sweetened the pill, just as the words gave the music depth.

On Steeltown the lyrics – the Falklands war, unemployment, tales of people trapped by circumstance and crushed by forces outside their control – and the intensity of the music combined to make something relentlessly grim.

It also gave the press another stereotype to play with: the dour Scotsman. In the eyes of the music press, the band were pompous and dreary and so not cool, darling.

The honeymoon was over. In January 1985 the band started recording the soundtrack to Scottish comedy movie Restless Natives. The results – the instrumental score freeing them from the burden of being spokesmen for a generation, perhaps – were as joyous and fresh as anything the band had made. After it was finished, however, Adamson threatened to leave the band. “Stuart was going through a tough period,” says Ian Grant, “and had left the band but hadn’t. [It was] more threat than meaning to. [He was] burned out from the success, relentlessly on the road, doing press, radio, TV and in the studio and not at home as much as he would have liked. Booze exacerbated the burn out.”

It was a wobble that may have accidentally cost them a spot at Live Aid. The band’s PR at the time was Mariella Frostrup, then wife of Richard Jobson. Frostrup “worked at Phonogram where Geldof was a lot of the time,” says Grant. “Gossip abounds in a small town like Dunfermline and Mariella knew Dunfermline gossip, being married to Jobson.” So Bob Geldof and Harvey Goldsmith thought the band had split and didn’t invite them. Big Country were onstage for the all-star finale but missed the chance to shine in front of a proportion of the two billion viewers that later took U2 to their hearts.

“Chris Briggs gave up drinking that very day,” says Grant. “Stuart had given up just beforehand and they concurred – cos AA is very kind of ‘You’re a member of the club’ sort of thing.” It looked as though Adamson had conquered his drink problem. “He bought a pub in Dunfermline and he used to pull pints, even though he didn’t drink. But then again, you never know how much he was hiding anything…”

Adamson later spoke about the period: “I stopped working and quit bevvying because I was drinking too much and I didn’t enjoy that too much either. You get used to having a drink now and again and then you just get used to using it and I didn’t like that about myself too much…”

Replacing Briggs was Dave Bates, an A&R man with the success of Tears For Fears and Def Leppard behind him. Bates’ job was to get them back in the charts. To do it, he enlisted Robin Millar, producer for Sade and Fine Young Cannibals – before sacking him when he heard the results and getting the album remixed by Walter Turbitt (previous credits: The Cars and Bad Brains).

The results spoke for themselves – single Look Away was a no.7 hit in the UK and no.5 in the US; the album, The Seer, went to no.2 in the UK – but the pressures on both the band and their A&R man to get a hit had caused frictions. “Bruce walked into the studio one day,” says Grant, “and the sound engineer, Walter Turbitt, was putting guitar on the album: ‘What the fuck’s going on here?’ Dave Bates had encouraged this guy to go and put some more guitar on the album. Now if he’d suggested it, that’s one thing – but to do it and Bruce walk in on him?”

“I remember recording Look Away,” says Tony Butler, “and it was a great popular rock track, with great sounds to it… Then we heard that the engineer who was part of the mixing team was sacked, and then the producer was sacked, and then somebody else was brought in that we didn’t even know… The next minute we found out they were putting bloody guitar parts on stuff and trumpets and shit and the whole thing was just taken out of our hands.”

How Adamson dealt with it is anyone’s guess. This is a man who prized honour and dignity (“masculine grace” in Jobson’s words) and famously despised record company bullshit – at one point quitting the Skids before the first album and sending a ‘resignation letter’ to Record Mirror bemoaning the fact that his teenage dreams of being a rock star were reduced to “the free meals and hand-outs of high-powered business executives”.

“He was a fragile character and sensitive guy,” says Grant. “Underneath any person’s veneer, people have sensitivities that don’t always show and it comes out in different ways. He was blown away by the success, completely blown away by it and he would drink heavily, which was his downfall several times in his life.”

1988’s Peace In Our Time was a blatant attempt to court America. Produced by Peter Wolf, the man behind Starship’s We Built This City and Heart’s These Dreams, it was a decent MOR rock album – all cowbells and keyboards and radio-friendly choruses – but ironically was the band’s lowest-selling album in the US to date, reaching no.160. By becoming US-friendly, they had lost much of what made them unique.

With the west unconquered, they looked to the East, playing Russia’s first international rock festival in August ’88 (Grant: “My pitch to him was: Bono – Amnesty International. Sting – the rainforest. You – culture. East meets West. You could be kind of a figurehead for that. He bought it.”).

To some people, it just added to the band’s public image as self-important, pompous do-gooders. The times were changing. 1988 was the year of U2’s Rattle And Hum. An outrageous success, it nevertheless took their image as earnest, bombastic and self-righteous retro-rockers to a tipping point. When they re-emerged with 1991’s Achtung Baby, U2 had been remade: now they were ironic, modern, dark, glamorous. The Alarm, Simple Minds and Big Country were left looking like yesterday’s men.

After Russia, Stuart Adamson decided to split the band. “He felt that it had reached its conclusion,” says Mark Brzezicki. “I suppose a little bit like Paul Weller with The Jam. We didn’t want to split up. Having said that, I knew in my heart it wouldn’t last. It was Stuart crying out to have a break.”

The drummer went to play with Sting, Tears For Fears and Fish – and then Big Country got back together again and “I physically couldn’t do it. I’d made commitments.” Eventually he played on 1991’s No Place Like Home album as a session musician “which was very odd because it was no different to me being in the band except I couldn’t commit to doing the tour…”.

Dropped by Phonogram, No Place Like Home came out on Vertigo and became their first to miss the top 20. 1993’s The Buffalo Skinners stalled at 25. It was also the first BC album not to feature Brzezicki on drums, adding to the impression that Brzezicki was not as committed to the band as the others.

It was a long-held view. In June 1985, Brzezicki had helped out another of Ian Grant’s bands of the time, The Cult. Making their Love album, the band had sacked drummer Nigel Preston after the recording of single She Sells Sanctuary. Brzezicki filled in for the video of that track, and helped finish the album. (Listen to Big Neon Glitter for the unmistakeable sound of the Brzezicki snare.)

“I was never less committed,” he says today, aware that this is a constant assumption. “There’s downtime. I wasn’t married – I’m still not married – others had families to go back to. When I stop, I still want to play…” Ironically for The Buffalo Skinners he was contracted to do Pete Townshend’s Psychoderelict album. Townshend’s regular drummer Simon Phillips then joined Big Country.

“So we kind of swapped gigs, which was really bizarre. And the story was that I’d left and later come back and that’s what stuck. And it’s always been a little black mark against me: ‘What did you leave for?’ But I never quit.”

Madchester. Rave. Grunge. Britpop. New record labels. Albums that didn’t sell (Why The Long Face? reached no.48, final album Driving To Damascus didn’t chart at all). By 1999 the band were a depleted commercial force. They asked The Alarm to support them on a few dates, and then – because they couldn’t afford to take a full support band to Europe – singer Mike Peters to support as a solo artist.

“I ended up sticking around with Big Country for a long time,” says Peters. “1999 turned into 2000 and so I spent a lot of time with them all – we all just got on well. We’re all musicians from the same generation and we can talk about things that maybe you can’t talk about with your friends at home. Our lifestyles are very rare. To talk to someone who has lived that experience and survived it is rare and I had that with Stuart. He was someone who had been through all those hardships, fighting for the integrity of their music, despite all the criticism…”

When in August 1999, the band released the single Fragile Thing, the world of music was a different place. “I felt a difference in temperature because I took a lot more interest in the business side of the stuff as the years went on,” says Butler. “And the business things did have a real impact [on morale] – and I know it had serious impact on Stuart definitely. The biggest one was when Fragile Thing came out as a single.”

Fragile Thing was A-listed at Radio 2 and the single looked a dead cert to make the top 40 until chart regulators CIN decided that the ‘pizza box’ packaging of the CD2 single had one too many folds in it. Sales would therefore not be eligible. The single went to 69.

“I know that really hurt Stuart a lot. I mean, big time,” says Butler. “It wasn’t fair and the album died because of it. A lot of things went sour because of that scenario. It definitely hit Stuart bad. And it really did kill the commercial potential of the band – losing that made the industry feel as though the band had no space.”

On tour in Germany at the end of 1999, Mike Peters realised for the first time that Adamson had a drink problem. “I never saw him drinking until one night in Germany when he started drinking in public again and everyone was like, ‘Whoa!’ He fell down some stairs and cut his face before a show and struggled his way through the gig. That was the first time I’d seen anything…”

Adamson had moved to Nashville where he had met another woman. Ian Grant had suggested the move in the hope of inspiring new song ideas (and it seemed to have worked: Fragile Thing was a well-crafted, country-tinged ballad, albeit one that had more in common with the Beautiful South than the Celtic rockers of old).

Grant: “I was thinking, ‘I’ve got to get him out of Dunfermline. He can’t get inspired by the same things – his roots, the working class, his wife – he needs a new challenge’. I set a load of meetings up with different heads of record companies in Nashville. One had a great idea: ‘I want to put country and Celtic back together and see what happens’.”

Adamson met singer-songwriter Marcus Hummon, with whom he would form a country act, the Raphaels, and through Hummon he met his second wife Melanie Shelley. “He moved there,” says Grant. “I don’t dwell on it, but it was the worst thing that ever happened really, cos he was out of sight then you never knew what was happening. He got comfortable in Nashville and I think he thought he could drink again.”

In October 2000 Big Country played their last gig in Kuala Lumpar, Malaysia. Adamson almost missed it when, drunk, he got on the wrong plane. “He was meant to go to LA to meet the band,” says Grant, “and he ended up in Indianapolis. Fortunately there was enough time to still make the gig.”

The gig was a disaster. “We were a karaoke version of what we were,” says Butler. “The whole thing was just painful and he was in such a bad condition, I just thought, ‘That’s it, I’m not having anything to do with this until things get better…’ I said to him, ‘I seriously think we need to have a break’. You know, stop, drop anchor for two years, just give everybody a chance to go off and clear their heads. I didn’t think we were helping Stuart by carrying on.”

“You couldn’t help Stuart,” says Watson. “Any alcoholic will tell you, you cannot help an alcoholic. He’s got to get that help for himself.”

- The Return of The Big Music

- Mike Peters has a new album and a tour to finish. He also has cancer…

- 10 of the best rock bands from Scotland

- How The Breakfast Club Killed Simple Minds

Between their last gig in October 2000 and his death in December 2001, Bruce Watson spoke to Adamson a few times by phone “but I could still tell he was still in hell,” he says.

Lillywhite called him too: “I spoke to him a month before he died, because everyone was worried about his drinking and his mental state in Nashville. I spoke to him and he said, ‘Steve, I’ve worked it out, I really can’t drink, I mustn’t drink, I’m happy now not drinking…’”

Mike Peters tried in vain to get in touch. “I was talking to Stuart and Ian about creating a project built around voices, almost like a British Crosby, Stills and Nash sort of thing. I’d been talking to Stuart saying, ‘Maybe we could get Mike Scott from The Waterboys to sing or Ian McNabb or Pete Wylie’. I was trying to call him in Nashville. I’d leave messages and I wouldn’t hear back.”

On November 15, 2001, Adamson left a bar in Atlanta, Georgia. His marriage to Melanie Shelley had split after two short years and he was facing a drink-driving charge that could have led to jail time. He fell off the wagon, hard.

He flew back to Nashville where, instead of going home, he stayed in various hotels. Grant hired a private detective to find him – to no avail. “He drunk solidly for eight weeks in hotels,” says the manager, “and every time we found out where he was he’d just checked out for another one.”

On December 4, he flew to Hawaii and checked into a hotel near Honolulu Airport where he requested the delivery of three bottles of wine to his room each day. He never left the room. On December 16, he was found by security hanging from a clothes rail. No suicide note was ever found. He was 43.

“It’s my birthday on the 17th of December,” says Grant. “I was having breakfast with my family and my mother said, ‘Have you any news on Stuart?’ and just as she said that the phone rang and I knew the number: it was Kim his sister. She said, ‘He’s died. He’s killed himself’. I went for a walk…”

“There is no understanding it,” says Grant. “Who knows what was in his mind. I know he was in a haze. I spoke to his AA sponsor: a ‘black haze’ they call it. You function, but it’s like when you go on a vacation – they call it going on a vacation – you end up somewhere and you don’t know how you got there.”

Today the band are back together, playing as a tribute to their friend and the music they made together, with Bruce Watson’s son Jamie helping out on guitar and Mike Peters on vocals. Onstage they leave a space where Adamson would have stood.

“Mark’s in goals at the back,” says Bruce, “and then Jamie and Tony are the wingers and Mike and I are like inside right and left. We leave the centre-forward spot vacant. It’ll always be vacant cos nobody will take his place. The audience – they can be centre stage cos they sing the loudest.”

The reunited band’s first gig was in Glasgow on New Year’s Eve 2010, the second in the band’s home town of Dunfermline. For Mike Peters it was a baptism by fire, but a challenge he’s relishing.

“I’ve had cancer twice in my life,” he says. “I’ve fought back both times. I say yes to everything because I’ve had to confront the fact that life could be over for me, so every day is uber precious. I was told I couldn’t have kids and now I’ve got two boys through the technology that’s out there. I’ve had to overcome some massive things, so to go out there and uphold Stuart’s name is only part of the big challenge of life.

“I’ve survived a lot to get this far,” he says, “and I wish Stuart could have had one more day to think about what was happening to him. Maybe he’d still be here, and I wouldn’t need to be and I’d be sitting here just as a fan, just like you, and we’d be going up the front and singing our heads off to the songs,” he shakes his head.

“That’s not gonna happen – but I still want to see Big Country and this is the only way we’re gonna have it.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 156.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.