How Pink Frost paid tribute to a fallen friend and gave new life to The Chills

An excerpt from Matthew Goody's comprehensive discographic history of the early years of pioneering New Zealand record label Flying Nun

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

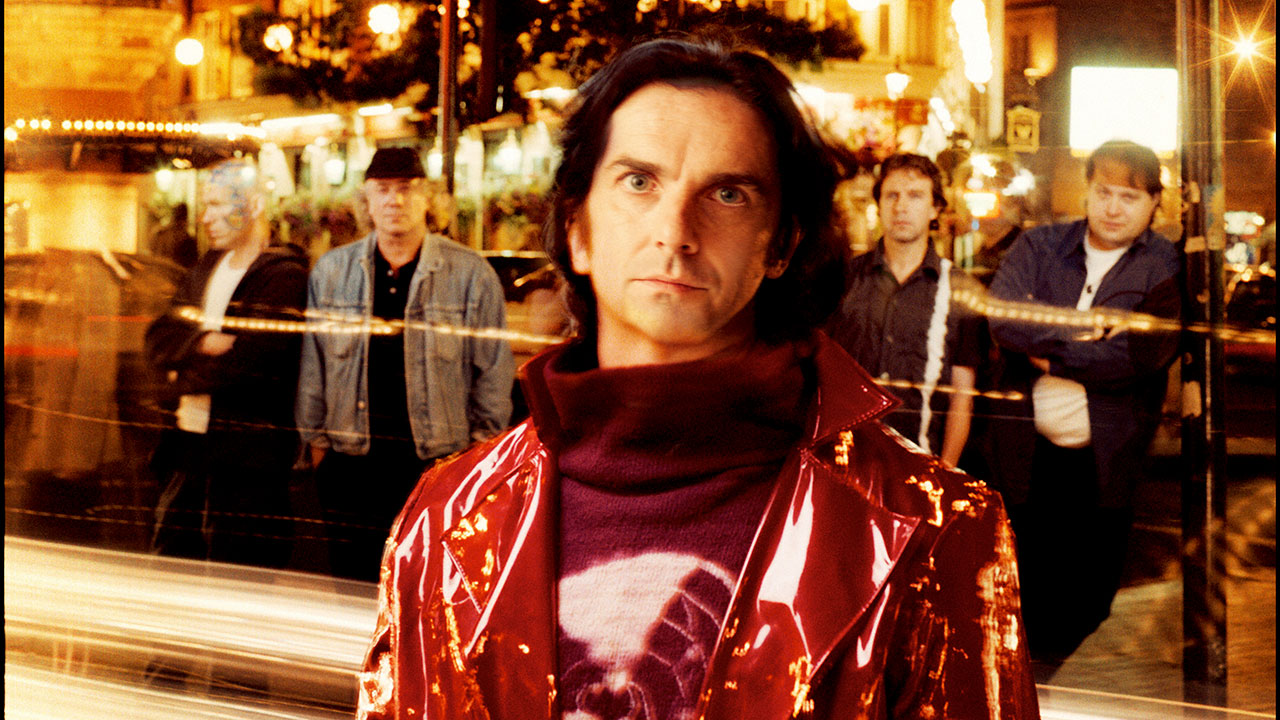

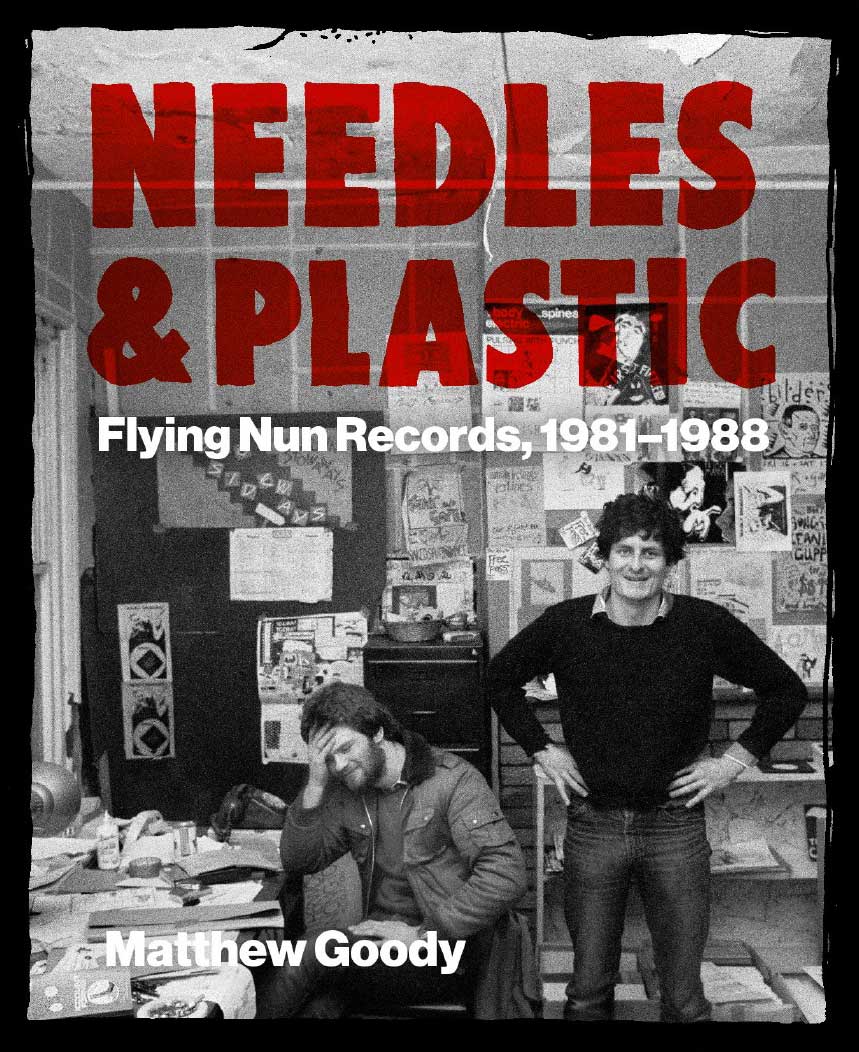

Matthew Goody's new book Needles & Plastics: Flying Nun Records 1981–1988, published by Jack White's Third Man Books, tells the story of the first seven years of New Zealand's Flying Nun, the pioneering Christchurch record label that exported the so-called "Dunedin sound", introducing the world to bands like The Chills, The Clean, The Bats, Straitjacket Fits, Tall Dwarfs, the Jean-Paul Sartre Experience and The Verlaines.

Needles & Plastics is a heroic piece of research, 436 large-format pages of extraordinary detail and rare photos, flyers, posters and memorabilia. In the edited excerpt below, Goody describes the development of Pink Frost, The Chills' other-worldly classic that was once voted the 14th-best NZ song ever.

Order Needles & Plastics: Flying Nun Records 1981–1988.

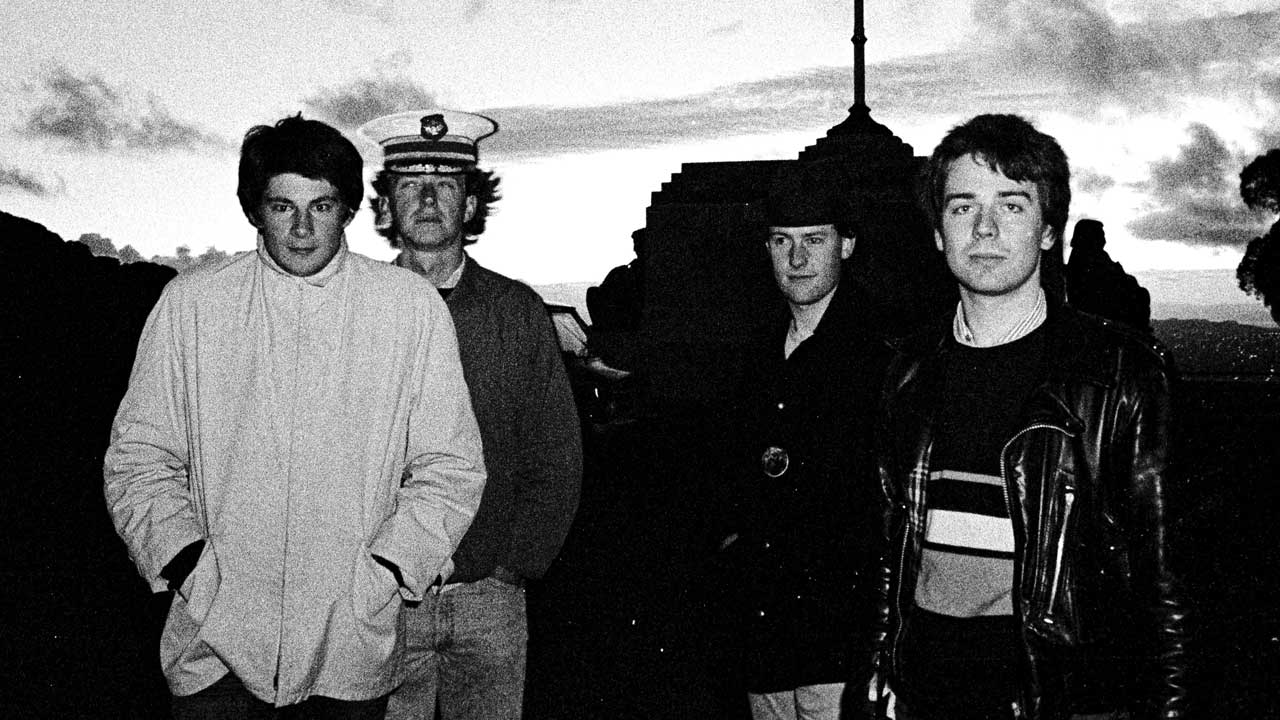

For the first three months of 1983, The Chills were dormant. They had not played live since the previous October. For frontman Martin Phillipps, the long stagnant period took its toll.

"That year not doing anything was quite bad," he lamented. "I wrote a lot of songs, but because I wasn’t playing, I didn’t develop."

By April, it looked like the hibernation might finally end. [Drummer] Martyn Bull’s regimen of holistic treatments [he had been diagnosed with leukaemia in June the previous year] had improved his health to a stage where he felt he could give the band another go. Anxious to play again, he returned to Dunedin and The Chills quickly started jamming at their practice space, joined by newly recruited keyboardist Peter Allison. Also coming along was ex-Clean guitarist David Kilgour who, much like Phillipps, had spent a number of months unsure of his musical future.

Though in essence phase six of The Chills, this five-piece version of the band opted to temporarily call themselves Time Flies in the hope that anything that came out of the sessions would be different and new. Early practices proved unproductive.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

"It was really exciting," Phillipps later said. "But there were daggers in people’s eyes half the time. No one was able to chuck around ideas at all. After five practices, Kilgour decided it wasn’t going anywhere and left. Following him a short time later was Martyn Bull. Though he had originally hoped his energy was back to a level where he could give drumming another shot, his health problems were simply too severe. Three months later, Martyn Bull died in Masterton on 18 July 1983. He was twenty-two. Bull’s death was a shock to the remaining members of The Chills.

In the weeks following their friend’s passing, they struggled with how to continue. For a brief period, a seventh phase of the band was tested, with ex-member Alan Haig returning to play drums, but it did not last. For bassist Terry Moore, the loss of his friend was particularly hard. He decided to step away from The Chills and regroup. "With Terry, after Martyn died, the music sort of lost its purpose," Phillipps told Rip It Up.

Initially with the new band it just felt so horrible practising without Martyn. So that was enough for him. For much of the winter, Martin Phillipps debated whether The Chills were at an end. "It was a period of meandering for me," he said. "Martyn’s wife and others didn’t want to see The Chills name used any more... I didn’t want to use it anymore."

Phillipps decided to drop The Chills moniker in favour of A Wrinkle in Time, a name taken from the popular science fiction novel. When Flying Nun got wind of the name change, they put pressure on Phillipps to revert back to The Chills. After losing best-selling act The Clean to a split, the label wanted to retain the name of one of its most popular bands.

Phillipps quickly found out that fans had a similar opinion. After playing just a few gigs as A Wrinkle in Time, it became clear that crowds thought of them as The Chills regardless of what it said on the poster. Grudgingly, Phillipps decided it wasn’t worth the effort and brought back The Chills, with ex-Blue Meanie Martin Kean now on bass, alongside Allison and Haig. Despite the revival of the name, Phillipps was still determined to honour Bull’s legacy.

In early January 1984, he linked up with Terry Moore in Auckland to revisit recordings of Pink Frost and instrumental Purple Girl that had been gathering dust. Phillipps, Moore and Bull had originally recorded the two songs at The Lab in May 1982 but abandoned them after the mixes weren’t good enough.

"I really had forgotten all about Pink Frost and Purple Girl and then we decided to remix them," said Phillipps.

Moving from The Lab to Progressive, Moore and Phillipps laid down new vocal tracks and added guitar to give Pink Frost new life. Phillipps’ haunting guitar riff melded seamlessly into a haunting pop tune written about someone waking to find they have killed their lover.

Asked about the added elements to Pink Frost in Rip It Up, Phillipps replied: "It’s changed everything. It’s exactly what we wanted." The Chills had their new single, a fitting goodbye to a friend.

Flying Nun released Pink Frost in late June 1984. The 7″ sleeve included a tribute biography to Martyn Bull on the rear sleeve, and "For Martyn" etched into the run-out of the vinyl. Profits from sales were promised to a cancer research charity. On 24 June, it entered the charts at #28 and made it to #17 the following week.

However, just as with [1982 debut single] Rolling Moon, Flying Nun scrambled to keep up with demand as stock ran thin. Reaching the top ten proved to be out of reach, but it still managed to chart for eighteen weeks, re-entering on three separate occasions. Its long stay was helped by a video for TVNZ shot months after the release date and some surprising airplay from Auckland radio stations.

"It got thrashed up there," Phillipps told The Press.

By November, Pink Frost had sold over 2000 copies, making it one of Flying Nun’s best sellers. More unexpected for both Flying Nun and The Chills was the attention Pink Frost received abroad. While the bands got virtually no radio support from their home-town stations in Dunedin, across the world John Peel started playing Pink Frost on the BBC.

Weeks later, reviews from Biba Knopf in NME and ZigZag gave the single even more exposure. Reviewing Pink Frost for Rip It Up, Russell Brown advised readers to buy the single "and make The Chills pop stars."

It looked like a possibility. After years of line-up shuffles and the tragedy of losing Martyn Bull, The Chills had survived to build a bigger audience than any other independent band in the country. This was in no small part due to the success of Pink Frost. It had helped them pay tribute to a fallen friend but also put the tragedy behind them. Now The Chills were ready for the spotlight.

Matthew Goody is a Canadian editor and publisher who has worked in the book industry for over a decade. A fanatical record collector and researcher, he has spent years combing through the archives and records stacks to compile Needles & Plastic: Flying Nun Records, 1981-1988, a comprehensive discographic history of Flying Nun's early years. He currently lives in Vancouver, Canada.