String Driven Thing

The former Curved Air frontman and violinist who hops between progressive rock and classical Darryl Way discusses his musical multi-tasking and expansive new solo album…

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

“I was thinking just this morning, that prog rock was a child of the late 60s, of The Beatles, their later albums like Sgt Pepper’s…, when they were experimenting,” says violinist and composer Darryl Way.

“Their immediate legacy was that the musicians wrested back control from the record companies of what an album consisted of and how it should be written.

“This gave rise to a huge amount of experimentation, but prog rock didn’t last long in its initial phase,” he continues. “Then the record companies realised that too much control was out of their hands and that’s when you started getting glam rock, the Tin Pan Alley songwriters came back with a vengeance and the charts were full of teenybop material.”

Luckily, Way was poised to take full advantage of that window of opportunity. After studies at Dartington College and The Royal College of Music, he formed Sisyphus in 1969 with keyboard player Francis Monkman, which transformed in early 1970 with the arrival of vocalist Sonja Kristina, into Curved Air. At this time, a violin in a rock band was still something of a novelty in the UK. There was Dave Arbus in East Of Eden and Simon House in High Tide, but few others.

“As a featured instrumentalist in a rock band, there weren’t too many people doing it at the time, which was good for me,” Way affirms. “It gave me all that room to make it up as I went along. I’ve been doing that for the rest of my life.

“With Curved Air, we saw a rock band as being a fantastic means of experimenting with music and we saw no kind of boundary,” he continues. “We wanted to include classical music, rock music and experimental music as well. In those days, it was all very new, so it gave you an empty canvas on which you could create weird and wonderful stuff.”

Curved Air initially broke up in 1972, followed by the formation of Darryl Way’s Wolf, an overlooked and short-lived progressive rock quartet featuring future Marillion drummer Ian Mosley and young guitar hot-shot John Etheridge. With sales failing to match the music’s quality, Way was hoping that Miles Copeland might manage them. But he had other plans and, in 1974, invested in a new version of Curved Air with his brother Stewart graduating from tour manager to drummer.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“We did another couple of years flogging around the universities. I’d had enough of touring and wanted to do something different. I was fed up being on the road all the time,” is Way’s succinct appraisal of his exit from the band in 1976.

Way has played with the group at reunion shows in 1990 then rejoined them when they reformed in 2008, but after an enjoyable couple of years, his dislike of touring caught up him again and he quit once more. But away from life in a rock band, Way has forged a parallel career as a composer, first allowing his classical proclivities full rein on Concerto For Electric Violin And Orchestra.

“I had all these great, highfalutin’ ideas about doing some serious music incorporating the electric violin,” Way explains. “We didn’t have the budget to record with a real orchestra, but we did a synthesized version of it. We used all the technology that was available in 1978 and Francis [Monkman] did all the keyboard work – that was the only way we could put it together.

“For its time I think it worked quite well. There was a precedent of doing synthesised classical music, like Walter Carlos with Switched-On Bach, so we thought that would be a way to go. I did it with full orchestra a few times – with the Royal Philharmonic for [TV arts programme] The South Bank Show and it was a different kettle of fish.

“Over the last 15 years I’ve done a symphonic choral work called Siren’s Rock which premiered in Plymouth. I’ve composed a few other orchestral pieces since then but those have only been recorded using synths. I also wrote an opera in 1996, The Master And Margarita which premiered in London, so there is always one side of me that wants to create large-scale works, but very few composers get commissions for these kinds of compositions. You can’t make a living doing it; it’s a labour of love. You do it for the kudos or whatever, but certainly not as a commercial prospect.” Way also records and still plays live with the classical crossover ensemble Verisma, featuring operatic tenor Stephen Crook, but with his new solo album, Children Of The Cosmos, he is “passing this way again,” as he puts it, into prog territory. He plays all the instruments on this eclectic collection of expansive tunes, with layered strings and keyboards, and synthetic percussion giving it a spacey, panoramic feel. He feels that once again he was given the chance to work on an empty canvas.

“It’s in the same spirit, but I’m not going back and using the same prog rock tricks like the extended solo passages, although there are some extended passages on it,“ Way says. “It’s a culmination of 40 years of experience, of putting everything that I know about music into one album.” Some of the huge chords looming out of the mix sound like electric guitar. “No guitars were harmed in the making of this album,” he quips. “A lot of the heavy metal chords are an electric violin using a fuzz box. “Lyrically, it’s a wistful look around me and my spin on what’s happening in the world at this moment and talking about some of my passions,” he explains. “I’ve been given the opportunity to vent my spleen on a couple of subjects. The Best Of Times is an acerbic commentary on the corruption of financial institutions, while the title track dreams of intergalactic colonisation.”

With Sergey, he has come full circle from the Curved Air showstopper, Vivaldi. If not the first, it was certainly one of the most successful classical rock fusions of the 70s. Way took an eight bar quote from the Four Seasons, to which he added a second melody and from then on it was original music, written in the style of the Italian baroque composer. Similarly, Sergey is an homage to Way’s most inspirational classical influence, Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev.

“The first section is in the style of his Classical Symphony – the last movement, full of fire and zest – and the next part is based on his Second Violin Concerto in G minor, the slow movement, but I’ve taken those chords and extended them slightly. It has the same kind of feel: the original is in three, mine’s in four. Other than the chordal structure, the piece is completely original.”

He also looks back to a less distant era on the appropriately psychedelic Summer Of Love. The song references the early use of Eastern instruments in rock and particularly violinist John Mayer’s Indo-Jazz Fusions albums Vols I and II from 1967 and 68. “I want to tweak people’s ears a little and take them back on that journey, because that’s what it was all about in London in the late 60s,” he says. “There was a feeling that by peaceful protest and music you could change things, but of course that was an illusion. But as I say in the song, ‘_It was _a glimmer of light in a cold, dark world.’”

Listening to Way’s beautifully phrased and dazzling violin playing on the coda of Summer Of Love and thinking back to his guest appearance on Gong’s 1978 album Expresso II, didn’t he ever think of launching his own prog/jazz fusion band back in the day? “I suppose Wolf was attempting that and John Etheridge was a fantastic jazz guitar player,” he replies. “I did attempt it later on with friends for fun. We had a kind of Mahavishnu Orchestra-lite ensemble. John Giblin was on bass, Laurence Scott on keyboards and the drummer was Stretch (Leonard Stretching). We didn’t have a name. It got to the stage when we were putting material together and it just fizzled out.

“The Mahavishnu Orchstra, the style of their music at the time, that was something I wanted to do. I felt that was exactly my bag and if [violinist] Jerry Goodman stepped aside I’d like to step in. But he never did!

“But jazz is not really my forte,” Way admits. “It’s one of the styles that I have not been able to master. Jerry Goodman’s also not a real out-and–out jazzer. In fact, we did threaten to do an album together, but that never came about. I’m a rock violinist,” he concludes, “with a little nod to blues, but mostly classical expression with a bit of guitar-influenced phrasing. That’s how I’d describe myself.”

Children Of The Cosmos is out now on Right Honourable. See www.darrylway.comfor more information.

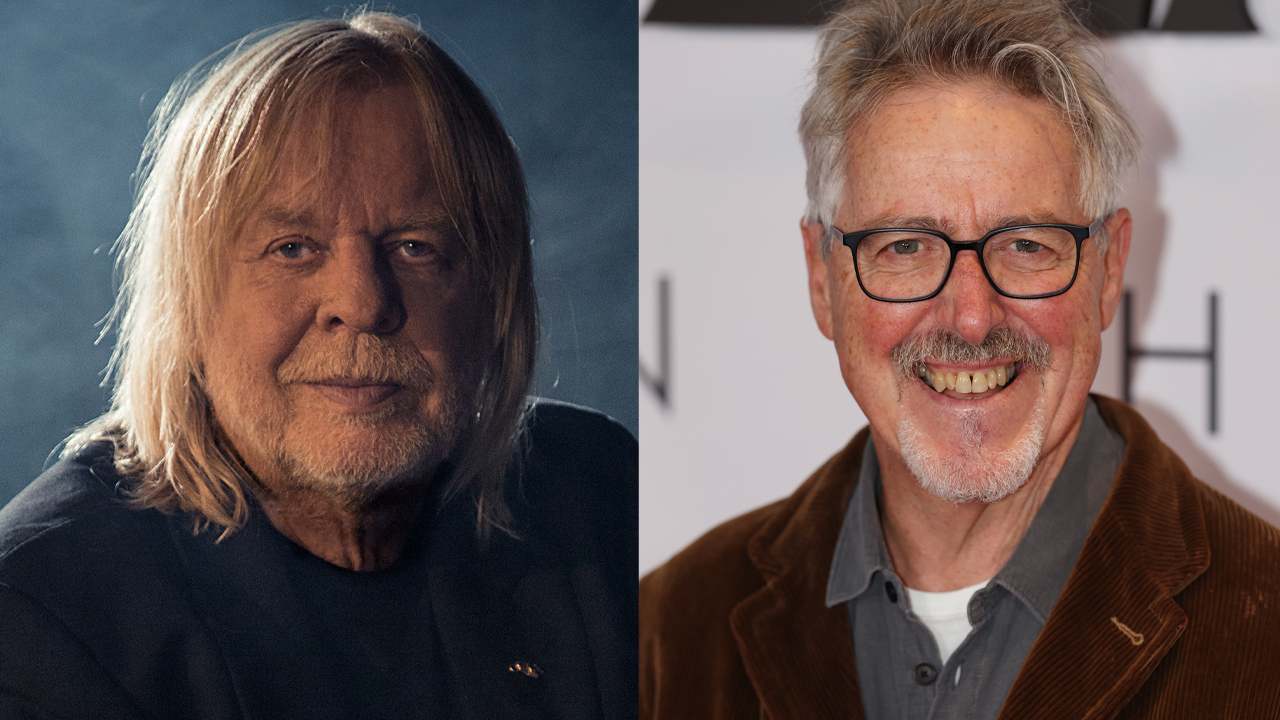

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.