Songs about body odour and a bath full of beans: The story of The Who Sell Out

The Who Sell Out is A Pop Art album of dazzling music interspersed with radio-style ads and jingles and released in an iconic sleeve: Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey spill the beans

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

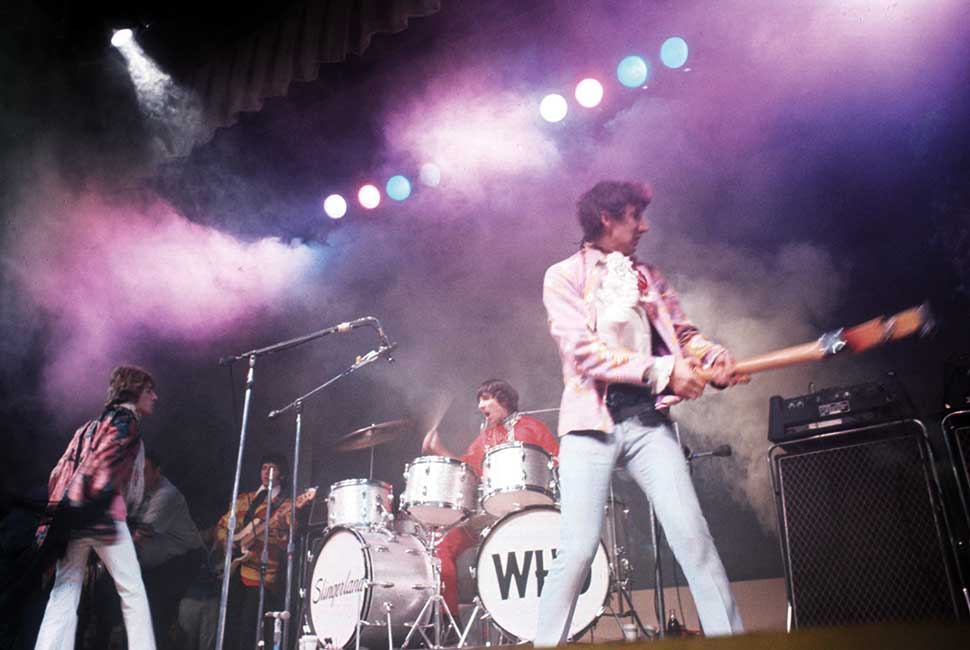

Inspiration can take many forms, but nothing stirs the creative juices quite like a looming deadline. Just ask The Who. In mid-September 1967 the band returned from an exhaustive tour of the US, a slog prefaced by an incendiary appearance at the inaugural Monterey Pop Festival, at which their gear-trashing performance left audience members open-mouthed. Rather than being allowed a breather back home, they were swiftly informed that new Who music was expected in the shops by Christmas.

“It was a surprise, and there are a couple of shades to that,” reflects guitarist and chief songwriter Pete Townshend. “One was that our managers, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, were diverted to a great extent away from The Who to running Track Records, which featured Marc Bolan and Jimi Hendrix.

"There was also a contractual obligation to Polydor, the parent company. They just needed a Who album, and we didn’t have one ready because we’d been working so hard. We’d been all over the place, incredibly busy. And although I had a lot of material, I didn’t really feel much of it was appropriate for The Who. So it felt to me like: ‘Oh god, how am I going to rescue this?’ There was a huge sense of panic."

The Who already had a tiny handful of standalone songs in the can, recorded at various US studios during rare breaks in the tour: Relax, Rael, I Can See For Miles. Townshend also had the seeds of other, equally disparate ideas. But the solution to the band’s immediate problem arrived via an ingeniously simple device that would link these songs together as a unified statement: the advertising jingle.

The new album started to take shape at De Lane Lea studios in London. The Who created spoof promo slots for Radio London, Premier Drums and Rotosound Strings, recorded in the brash ad-speak of 60s pirate radio. Bassist John Entwistle came up with humorous, minute-long odes to Heinz baked beans and Medac spot cream; Townshend brought along the song Odorono, ostensibly about a brand of underarm deodorant.

“I think the idea of doing commercials was already knocking about in my head,” Townshend recalls. “I’d already written two songs for [co-manager] Kit Lambert for the American Cancer Society – Little Billy and Kids! Do You Want Kids? – and I had Odorono, about a girl who loses a record contract. It wasn’t meant to be a commercial, it was just a song about body odour.

"That’s the kind of thing I was writing at the time, totally off-the-wall. And it just came up when we brainstormed. Subsequently, Kit Lambert pulled it together and made one half of the album into an emulation of a pirate radio station. For me, that just saved it.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The album, soon to be titled The Who Sell Out, also happened to be very timely. In August 1967, the British government had passed the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act, which outlawed pirate radio in the UK. The offshore stations had been a lifeline for pop music fans over the previous few years, as well as providing crucial airtime for bands and artists including The Who. In what could be seen as a cynical move, the BBC now attempted to woo the same audience with the launch of their own pop station, Radio 1.

Bold and brilliant, The Who Sell Out was both a valedictory salute to a lost art form and a satirical take on 60s consumerism.

“It was really done as a tribute to those ships that used to beam that wonderful music,” says frontman Roger Daltrey. “We’d been raised on pirate radio for the last five years. For the first time ever we’d had DJs, these kinds of renegade people, who were just so happy to be playing the music they loved. It was really special.

"Although we’re one band playing all the music, the album sounds exactly like a pirate radio show with the jingles. To me it still sounds a lot better than modern radio. It’s one of my favourite Who albums.”

Just as the Summer Of Love symbolised a seismic shift in the counterculture, The Who found themselves in transition in 1967. The band were still masters of auto-destructive chaos on stage, but they’d ditched the R&B and mod connotations of their early years.

Townshend’s songwriting had begun to deepen, as evinced on A Quick One, While He’s Away, the epic closing track from the previous year’s A Quick One, their second album. He’d also moved towards colourful character studies with recent songs like Happy Jack and Pictures Of Lily, a style that he began to perfect on The Who Sell Out gems such as Tattoo and the winking Mary Anne With The Shaky Hand.

Such creative evolution, Townshend suggests, “might have been inspired by the success of A Quick One, While He’s Away, which was a little song cycle that I’d done. What we used to call the mini-opera, which was maybe four or five very short thematic pieces strung together. It was quite clear that we’d hit on something really quite important and precious, the ability to tell stories and to go quite deep.

"I think A Quick One, While He’s Away is about child abuse and I think it’s about rape and I think it’s about women’s rights. But for me at the time, I wasn’t thinking of it in those terms. I was thinking just in terms of a story about somebody being deserted.

“It’s kind of an autobiographical story, I realised many years later,” he continues. “A child being deserted and being abused while the parents are away or the mother is away and then coming back and life being okay. I think the characters in the mini-opera were very real to me. I could see them and I could feel them. So when I started to go back to the idea, with the song Rael, I was on a mission to try to write a real opera. And I suppose I meant a rock opera.”

Townshend, who suffered physical and sexual abuse as a child, would go on to process the experience more fully on 1969’s multi-faceted Tommy. Meanwhile, on a formal level the striking Rael provided a platform for him to get there.

Daltrey cites Kit Lambert as an important figure in Townshend’s move away from conventional pop music. The son of composer Constant Lambert, Kit introduced The Who’s songwriting captain to the classical music of his godfather, William Walton, as well as to figures like Henry Purcell.

“Kit loved pop singles, he loved rock’n’roll,” Daltrey explains. “But he always thought that the music could actually do and say so much more than it was doing at the time. That was always his dream. He hated what classical music had become, the fact that it had become pompous for this overfed middle class with their noses in the air. Composers like Mozart wrote songs for the people and it was the pop music of its time. So Kit always wanted to give rock a bigger foundation.”

As a working unit too, as 1967 wore on The Who were moving away from standard convention. They’d flown to America for the first time that March, making their live debut on an old-school Murray The K theatre bill in New York. By mid-June they were sharing a stage with Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin on the closing night of Monterey.

The contrast was stark – from jostling for position with comedy troupes and novelty acts on the East Coast, to being at the epicentre of the psychedelic youthquake out West. Acid had replaced pills as the drug of choice. And while The Who were never likely to align themselves to the hippie scene or its attendant paraphernalia, Townshend was keen to experiment with LSD.

His brief flirtation ended after a particularly terrifying trip in which he underwent an out-of-body experience on the flight home from Monterey. Other, more meaningful factors played into Townshend’s development as an artist, not least a burgeoning interest in spirituality.

“At that time I was starting to get interested in [Indian spiritual master] Meher Baba,” he says. “I was starting to get interested in metaphysical ideas and meditation, the kind of stuff that The Beatles had been doing, and hanging out with Brian Jones, who’d met the Maharishi. It was an exciting time.”

1967 was a royal year for psychedelia, with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as its crowning jewel. Pink Floyd debuted with The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn; Hendrix hit a double whammy with his Are You Experienced and Axis: Bold As Love albums.

Across the Atlantic, Love paraded the exquisite Forever Changes, while Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow included the counterculture’s defining hymn to turning on, tuning in and dropping out, White Rabbit. The Who seemed like dissidents by comparison.

Townshend acknowledges a debt to Sgt. Pepper’s experimental zeal, but says he was galvanised “more by some of the extraordinary harmonic leaps that Brian Wilson had taken in [The Beach Boys’] Pet Sounds. Going from songs about the beach that were not much different than those by Jan & Dean to a song like God Only Knows is just a huge leap. It was inspiring to me and obviously to many others. I was just trying to make the music interesting.”

Certainly The Who Sell Out has an outlier sensibility. It’s psychedelic only in terms of the rushing Technicolor of the songs, which feel instead like a confluence of Townshend’s love of Pop Art, English baroque music and windmilling rock’n’roll. There’s also a heightened sophistication to many of the arrangements and chord structures.

The standout is I Can See For Miles, a smouldering firecracker of a song, riddled with paranoia. In May 1967, while promoting Pictures Of Lily, Townshend had referred to The Who’s sound as “power pop”. That term later came to signify an entire genre.

“I suppose it’s about writing pop songs that have a little more going for them than the usual subject matter,” he reasons today. “I think powerpop was just an attempt to say: ‘Listen, pop songs are not going to be about what they’ve been about any more. They’re going to have power and energy and colour and humour.

"And they’re going to be more important and they’re going to be much more emphasised. They’re going to be more mischievous. They’re going to be more dangerous, possibly.’ In a sense, the powerpop thing was a recognition, during that time in sixty-seven, that the function of the pop song had changed.”

Another key track was Tattoo, whose vaguely jocular lyrics belie a more profound discourse on the notion of masculinity. It’s a classic in the style of previous singles Pictures Of Lily and I’m A Boy, both of which had touched on a similar theme.

Townshend explains that I’m A Boy, released in August ’66, arrived at a time when “homosexuality was still illegal in the UK, so these adventures had to be couched in vignettes of humour and irony”. As for his own preferences, he adds that he was probably pansexual at the time: “I think I was ready to fall into bed with anybody that would have me.”

In terms of music, Tattoo displays a new level of finesse in Townshend’s songwriting. It was conceived during The Who’s recent US tour with British pop act Herman’s Hermits.

“It was a long sixteen-week tour,” he recalls. “A charter plane and a gig every day. We had three days off in Las Vegas, and I wrote Tattoo while I was there. I think I was very conscious of the fact that somehow there was a poetry behind all this stuff. It’s a very important song. And it’s so interesting that the reason The Who still sing it today is because Roger just loves it.

"I think he loves challenging himself with the idea of ‘what makes a man a man’, because when he was a young guy he talks about the fact that he was short and became a bully, a fighter. Roger was a notorious fighter in the neighbourhood we grew up in. I remember doing a gig in Glasgow and he got into a fight with about ten Glaswegians and knocked them all out. He was an incredibly efficient fighter."

For all Daltrey’s commanding presence on Tattoo, I Can See For Miles and Rael, it’s instructive to note that The Who Sell Out features an unusual amount of lead vocals from the guitarist. Townshend is front and centre on, for example, Odorono, Our Love Was, Sunrise and Can’t Reach You. This wasn’t necessarily by design. Townshend has a theory.

“Jimi Hendrix was using the studio [recording Axis: Bold As Love] on the days that we weren’t in there,” he says. “And at that time Roger’s girlfriend, Heather, who became his wife, had been seeing Jimi. I don’t know whether or not this is turning into sort of silly gossip, but I think he wasn’t around as much as he would normally be. He used to enjoy being in the studio, and suddenly he was gone.

"So I think what actually happened was that I was finishing the songs as I was finishing the vocals, imagining that Roger would come in and replace mine. But he just wasn’t there. I think it had something to do with him being concerned about Jimi Hendrix stealing his girlfriend. I think Heather is the redhead he wrote Foxy Lady about, so I think there was some intrigue going on there. I’ve never spoken to Roger about what really happened.”

Given the short lead time and Townshend’s initial lack of faith, it’s a wonder The Who Sell Out got made at all. Referring to the ultimatum laid down by co-manager Chris Stamp on The Who’s return from America, Townshend remembers “a difficult situation. I would, of course, have written songs eventually. There’s always been a problem for me to find the time to write songs, make demos of them – which takes me a long time – then go into the studio and record them all over again with the band. Then go out on the road and play them.

“The guys in the band always wanted the album to be ready by the time we landed,” he continues. “I can remember Roger Daltrey once saying to a newspaper that ‘Pete writes his best stuff on the road’, which was his dream and his fantasy. But I never wrote on the road, because I needed a studio. So I was always under the gun.”

Despite everything, The Who Sell Out is an undoubted masterpiece. Released on December 15, 1967, it invited ready comparisons to the Rolling Stones’ album Their Satanic Majesties Request, which came out the previous week. But it was light years removed from the latter’s contrived psychedelia. The Who pushed against expectation without sacrificing their identity.

The same couldn’t be said of the Stones. Even the packaging for The Who’s record was far superior. On the cover of Their Satanic Majesties Request the Stones, wearing daft panto hats, stared sourly from a garish 3D backdrop. The Who, by contrast, accentuated the Pop Art elements of the music by commissioning art director David King and designer Roger Law (both of whom worked for the Sunday Times) to create what has since become an iconic sleeve.

Using giant props made by Law’s wife, Deirdre Amsden, the pair worked up four visual skits based on specific songs from the album. Photographer David Montgomery did the shoot at his studio in Chelsea. For their individual photos on the sleeve, Townshend pampered himself with roll-on Odorono; Keith Moon said goodbye to acne with a tube of Medac; John Entwistle, in the arms of a bikini-clad model, enjoyed the benefits of the Charles Atlas bodybuilding course; Daltrey sat in a tub of baked beans, cradling an outsized Heinz can.

The whole thing served as a fabulous send-up of 60s advertising. King and Law went so far as to give the as-then unnamed project a title: The Who Sell Out. The band were thrilled with the finished packaging, even if Daltrey was made to suffer for his art, having caught pneumonia afterwards.

“We’d just come back from Hawaii on the Herman’s Hermits tour,” he explains. “We’d only been home for five days. I drew the short straw of getting to sit in the baked beans. Unfortunately for me, the beans had been put in cold storage. They were freezing cold, and after sitting in them for an hour my teeth were chattering. So they put an electric fire at the back, and by the end I was literally cooking! I did get very sick from that.”

The release of The Who Sell Out held long-term significance for the band. Daltrey, in particular, had begun to inhabit his true persona on the immense I Can See For Miles, reaching fuller fruition some 15 months later, with Tommy. “Previously, the original material I was singing was from a person with a lost identity, searching for home,” he offers. “Tommy brought me home. All of a sudden I knew exactly what I was doing. I knew exactly who I was. I didn’t fear anything. My vocal style changed because of the type of material I was singing. It was its own thing.”

For Townshend, the songs on The Who Sell Out signalled the start of his personal spiritual and metaphysical quest that would continue for the rest of his career. Certainly the grand visions of Tommy, Lifehouse (initially truncated into Who’s Next) and Quadrophenia couldn’t have happened without it.

Unlike any of the above, however, The Who Sell Out bears its weight lightly. It never forgets to have fun, offsetting its intellectual vigour with an impish sense of joy and subversion. It’s an album that delights in the untold possibilities of pop music, made by people who were only too eager to explore.

“I very much enjoyed that process,” concludes Townshend. “It felt to me like I was discovering things about the guitar that I hadn’t discovered before. I was finding ways of creating new harmonies and textures and new sounds. There were challenges going on for me and I was rising to them. And sometimes I was pulling them off.”

The Who Sell Out Super Deluxe Edition is available now via UMC/Polydor.