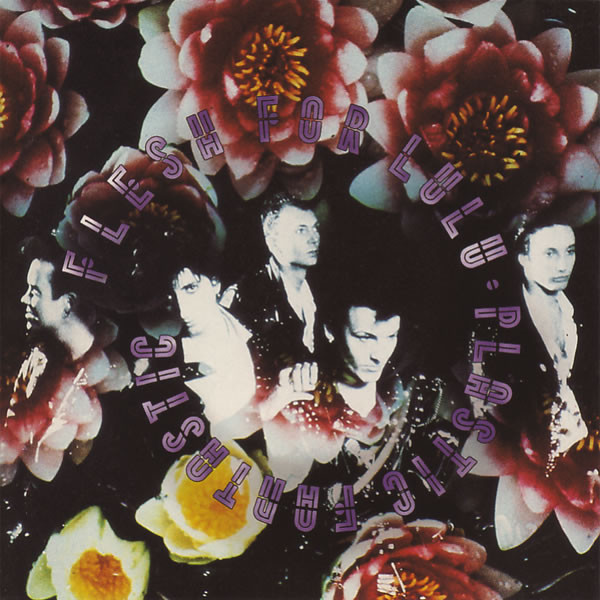

Long Live The New Flesh was recorded over three months with Mike Hedges at Abbey Road, Studio 2. The Beatles recorded Come Together in that room. Johnny Kidd & The Pirates did Shakin’ All Over there. Matt Munro sang From Russia With Love. Somehow New Flesh still came out sounding like it was recorded in LA for American radio. Which was exactly the idea. New UK record label Beggars Banquet, says Kevin, “wanted a record that would sound big and they could shift in America. I mean, so did we. Mike [Hedges] had been told to deliver that sound.”

“We went in the studio with Mike Hedges,” Nick said, “and on the first day we started playing and getting the monitor mix together and me and Rocco were like, ‘Where’s the fucking guitars, man?’ and [Hedges] said, ‘Do you want guitars?’ We were like: ‘Oh fuck’…”

Whatever, Mike Hedges did what he was asked to do: New Flesh was their biggest-selling album and took them to a different level in the States. Today, the production sounds a little bit 80s – polished and over-produced – and the songs a little bit thin. “I can’t stand it,” Nick said. “And an album’s a bit like tattoo. I’ve been carrying it around, this insipid, fucking…”

The songs were solid (Good For You, Lucky Day, Sooner Or Later) but there were only a few bonafide FFL classics. The Replacements woulda sold their Ma for Kevin’s contributions – Postcards From Paradise (later covered by Paul Westerberg and the Goo Goo Dolls) and the effortlessly cool Sleeping Dogs, while Nick’s Siamese Kiss stomped with a gleeful Glitter Band beat.

This time the band’s influences – always eclectic – threatened to totally undermine the Flesh For Lulu brand. “Around the time of Long Live the New Flesh, Nick had this really big thing about Prince,” says Kevin. “He loved Prince, he thought the guy was a genius – we all did – but we had to steer him away from the Prince element a little bit because we thought it was getting a bit away from the sound of the band…”

To an outsider, it felt like a cynicism had crept in. The edges had been filed off. Gone were the days of horny lesbian nuns and ‘I’m gonna break both his legs’. Instead, the artwork featured a corny air-brushed logo of a winged heart against a city skyline. Songs like Crash were breezy and nice. Hammer Of Love nailed Peter Gunn horns and a funky bassline to a lyric about table-top shagging. And then there was Way To Go, which did sound a bit like Simply Red.

Way To Go was another one of Kevin’s. The stress of recording it – the search for perfection and the drive for success – signalled the beginning of the end for Rocco. “It’s a fantastic song,” he says, “but the way it was played… There was one line, I might have been a millisecond out and Kev made me play it and play it and play it. And finally I went, ‘You know what? You play it.’ And that was the seed that went on to the next album. It got to the point that whatever I played, it just wasn’t good enough. And I thought, ‘You know what? I’m not in this band anymore.’”

There was a bigger picture. Kevin was reaching breaking point: writing songs, playing bass, managing the band. It was around this time that Perry Watts-Russell got involved. Kevin’s preferred choice for manager was a woman called Janet McQueeney, but Nick and Rocco wouldn’t go for it. Then the Watts-Russell thing ended in disaster.

“He got the hump about that,” says Rocco.

“It drove a wedge between us all,” agrees James.

Trust Hollywood to promise a happy ending. The movies of John Hughes – actually made and set around Chicago – were single-handedly changing the fortunes of British alternative rock bands, with soundtracks that were as smart and quirky as his characters. Hughes was a music nut with an Anglophile’s knowledge of new wave and alternative rock. “I always preferred to hang out with the outcasts,” he said, “‘cos they were cooler. They had better taste in music, for one thing…”

Simple Minds got a US no.1 out of the soundtrack to 1985’s The Breakfast Club with (Don’t You) Forget About Me. The Psychedelic Furs had their biggest UK hit with the title track to Pretty In Pink, and the soundtrack album also included songs by New Order, Echo & The Bunnymen and OMD. Suddenly, British alternative music had something bigger to aim for than four cans of Kestrel at the Retford Porterhouse.

Peter Webber – the band’s former manager – was working with Psychedelic Furs and told Flesh For Lulu that Hughes was looking for a new song for his next movie Some Kind Of Wonderful. James bought himself a 4-track and knocked up I Go Crazy quite quickly.

“Nick tidied it up,” he says. “I had a big argument with him about it, actually. It was much darker. It really was ‘I go crazy’. It was a song about depression, about not being happy, punching a window over some girl I’d been seeing.”

Nick re-wrote some the lyrics, softened it up a bit for Hollywood, and they got Pet Shop Boys producer Stephen Hague in.

“He was a bit of a twat,” says James. “He had this girl who’d sit and roll him spliffs. He tried to get a songwriting credit because he changed a chord in the middle eight. He did a flat A instead of a major.” They had to take it to two musicologists to avoid giving him a percentage of the royalties.

It was their biggest hit – a cool Billy Idol-like pop song that was a great vehicle for Nick’s voice. In the video, the band are heavily styled and Nick is all exaggerated arm-movements. He’d decided he didn’t want to play guitar anymore. He wanted to be a frontman. He had a new persona he wanted to try out: Nick Nasty.

“He just wanted to be Iggy Pop or something,” says Kevin. “I think that ‘Nick Nasty’ was his idea. But then Ivor Wilkins, our tour manager, started calling him ‘the harsh Marsh’ – Nick Nasty, the harsh Marsh. Nick used to get slightly peeved because he always thought we were taking the piss a little bit.”

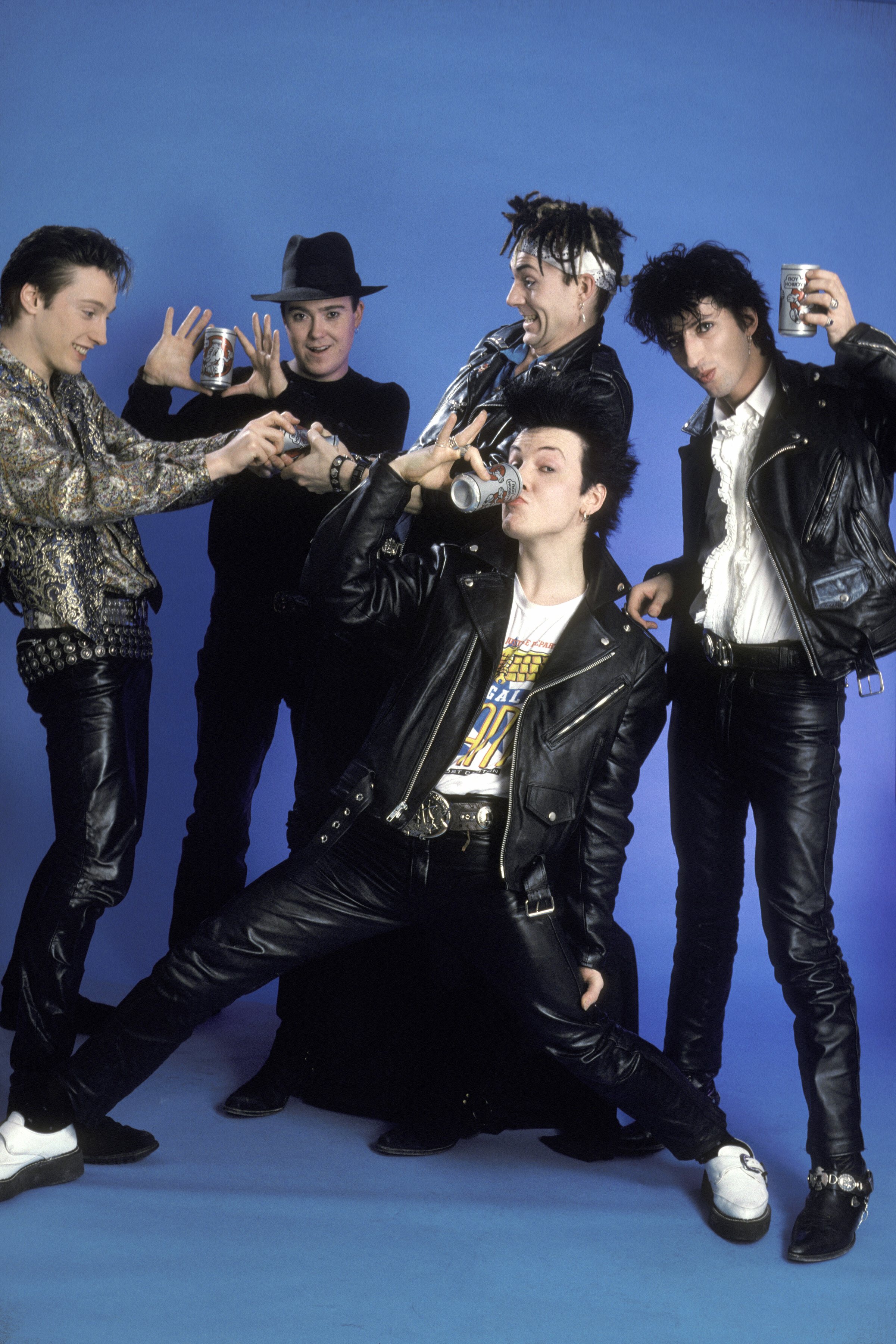

They had brought in a fifth member during the recording of New Flesh: Derek Greening (aka Del Strangefish), formerly of Peter & The Test Tube Babies. Derek remembers first meeting them at a show in Germany where Flesh For Lulu were supporting the Test Tube Babies. “There was a riot outside between punks and skinheads,’ he says. “Rocco and Nick were in the dressing room going, ‘Are we gonna be alright?’”

Derek was a fan of Big Fun City and when he moved from Brighton to Brixton he “used to drink down the Prince Albert on Coldharbour Lane, which was a hangout for punks and goths and stuff. We just became mates and they asked me if I’d do a bit of guitar. Nick wanted to stop playing guitar on stage so that he could be free to move around more, be a bit more Iggy Pop.

“So that’s how it started – I didn’t realise I still be doing it eight years later.”

Maybe one day someone will make a movie about Flesh For Lulu and, if they do, this will be the bit they go to town on. The band’s gritty beginnings in Brixton and the Batcave will be squashed into the first 20 minutes and the rest will play out like a goth-rock Entourage – set in the American sunshine, with the band in shades and black leather jackets, surrounded by beautiful women, Hollywood directors and flash cars.

“My favourite memory,” says Derek, “is a tour we did with The March Violets on the back of Some Kind of Wonderful. Paramount Pictures backed the tour. I’d toured America before in the back of a Transit van with 24 other guys with hairy arses, so this was something else. Paramount was picking up the tab, so we’d get driven everywhere in Limousines, stay in 5-star hotels, and everything was free. Back home in Brixton we’d have padlocks on our fridges. Here there was free champagne, free Jack Daniel’s, free everything.”

At the end of the tour, they played at the Palace in LA. It was, wrote the LA Times, a big night “for scores of just-about-to-be-somebodies”. Some Kind Of Wonderful premiered earlier that night at the Chinese Theater and the audience at the Palace included John Hughes, Eric Stoltz, Lea Thompson, Mary Stuart Masterson, Andrew McCarthy, Molly Ringwald, the Bangles, Andy Summers, Michael Des Barres, the Beastie Boys and Rutger Hauer.

They had signed to Capitol. They were playing bigger venues. John Hughes had signed them to his publishing company. Aerosmith’s Joe Perry said that Long Live The New Flesh was his album of the year. They got the big tour bus, they played the bigger venues, they stayed at the big hotels… It was the rock’n’roll dream come true. Success, glamour, on the cusp of the big time. But something still wasn’t right.

“John Hughes used to take us out,” remembers James, “and he’d say, ‘Here’s my number – if you need anything, just call me’. And you’d ring it and it’d be dead. A dead number.”

“The last album,” says Rocco, “was just a nightmare.” They settled on this guy Mark Optiz, an Aussie who’d produced Australian bands like Cold Chisel and Jimmy Barnes. Optiz was part owner of INXS’s Rhino Studios in Sydney and suggested they do it there. Beggars Banquet, hoping that a little bit of INXS’s magic would rub off on them, said yes.

The band arrived in Australia exhausted and sick of the sight of each other. There was a lot of drinking and a lot of downers. By his own account, Kev was driving everyone mad, himself included. “I probably had a few breakdowns and didn’t even notice,” he says. “Just came out the other end and started again.

“I was a control freak. I was really trying to control the destiny of the band, not for my own ends, but to get us where I thought we should be. It’s not a good idea to be a manager and be in the band. You lose the dressing room, as they say. And I really did. The more you think you’re doing it for everybody’s benefit, the more they resent you for it.”

Around that time, James discovered that a childhood accident – where he’d crashed his bike and impaled himself on the handlebars (“I very nearly died, it ripped my bowels open. I had a blood transfusion, septicaemia, everything”) – had left him with a permanent back problem.

“I went for an X-ray and they were like, ‘Oh, you’ve broken your back, actually’. I had no idea.” To counter it, the doctors told him, he had to stay fit. He’d have to give up the life of excess he’d been living for the past few years.

In Australia, he started going to the gym. Nick didn’t approve. “Nick couldn't handle the fact that I went swimming or went to the gym,” says James. “He thought it was really unrock’n’roll. I said, ‘Nick: I have to. I can't physically play if I don’t’.”

The songs weren’t there. James hadn’t written much, Kev didn't want to and Nick was trying to do his funky Prince kind of thing. Derek stepped in. “His songs were a sort of poppy,” says Kevin. “I suppose, more commercial, but I didn’t really think they had the intensity of the earlier Flesh For Lulu songs.”

To add insult to injury, it turned out that the deal Derek had signed meant that, where the original four split the royalties on each song, Derek kept all his royalties to himself. “Someone should have stood up to him,” says James, “but by that point…”

Nick later told Vive Le Rock magazine that "Del wrote Time And Space, which is without doubt the most stupid, saccharine piece of shit pop song, without any redeeming features. Of course the record company fucking loved it and stuck it straight out as a single.”

Which was a bit naughty of him, really, and might just illustrate Kevin’s points about Nick's failure to step up at times. Nick was the singer, frontman and founder of Flesh For Lulu. If he didn’t like that song, and if he didn't want it as a single, maybe he could have shown some leadership – refused to record it, halt its release. It just wasn’t his way.

“Nick was quite a humble or non-confrontational guy,” says Kevin. “He wanted what he wanted but he didn’t want to have to bully people or to have to drive at it in order to get it.”

For Rocco it came to a head during the recording of the album opener, a song by Kevin called Decline And Fall. “There’s a lot of guitars on that,” says Rocco, “and they’re really quite intricate and I’m not the greatest guitar player. What I’m good at is just doing weird shit, making them sound different, you know? I spent two days with the engineer Al, 12 hours a day – I mean, we were doing coke and whatever, having a great time – and at the end of it Kev walked in.

"He didn’t even listen – this is why I knew it was bullshit – he walked in and after about four bars, walked back out again and went, ‘This is rubbish. Get Nick to play it.’ And I thought, ‘I’m not even going to bother playing guitar’. I just went off and got drunk in the bars in Sydney. I walked out of that record, literally half way through it.”

Nick, meanwhile, was having at go at James over his drumming. “I knew my limitations as a drummer,” says James. “I had the energy but I was never going to be Topper Headon. And that’s what Nick wanted, or thought he did. We all started to slag each other off. Kev would say to Nick, ‘You’re out of your head. It’s hard to get a vocal out of you, you’re just slurring’, too much coke or whatever.

“Rocco was too pissed. Kev was imploding. Derek was in the band, and really all the best stuff was written when it was just the four of us. We were top of college radio in America and playing quite good venues and then we went to Sydney and it all blew up in our faces.

“We lost sight of what we all did. We became too success-hungry. We were all trying desperately to break through to next level and we lost sight of what made us good.”

The finished album, Plastic Fantastic, was pretty well represented by its two first singles, Decline And Fall and Time And Space: two completely average, characterless, and instantly forgettable rock songs.

“The songs were less sexy, less sensual, and they lacked some of the charm that those early songs had,” says Kevin. “It seemed to be devolving back into this sort of – I don’t even want to say it – pub rock kind of thing, where you’ve got these rocking songs, but there’s nothing mysterious or alluring about them. It’s just straight ahead boogie.”

The best songs were Nick’s. Stupid In The Street sounded like like New Sensations-era Lou Reed – warm and doo-woppy – while the title track closed the album with a slow funk that might have been the closest he got to nailing the Prince vibe he was looking for. 'I'm a sci-fi baby of the twenty-first century,” he sang at the end. 'That’s me/Plastic fantastic/I can feel it when you talk/See it when you walk that way… Bye-bye.'

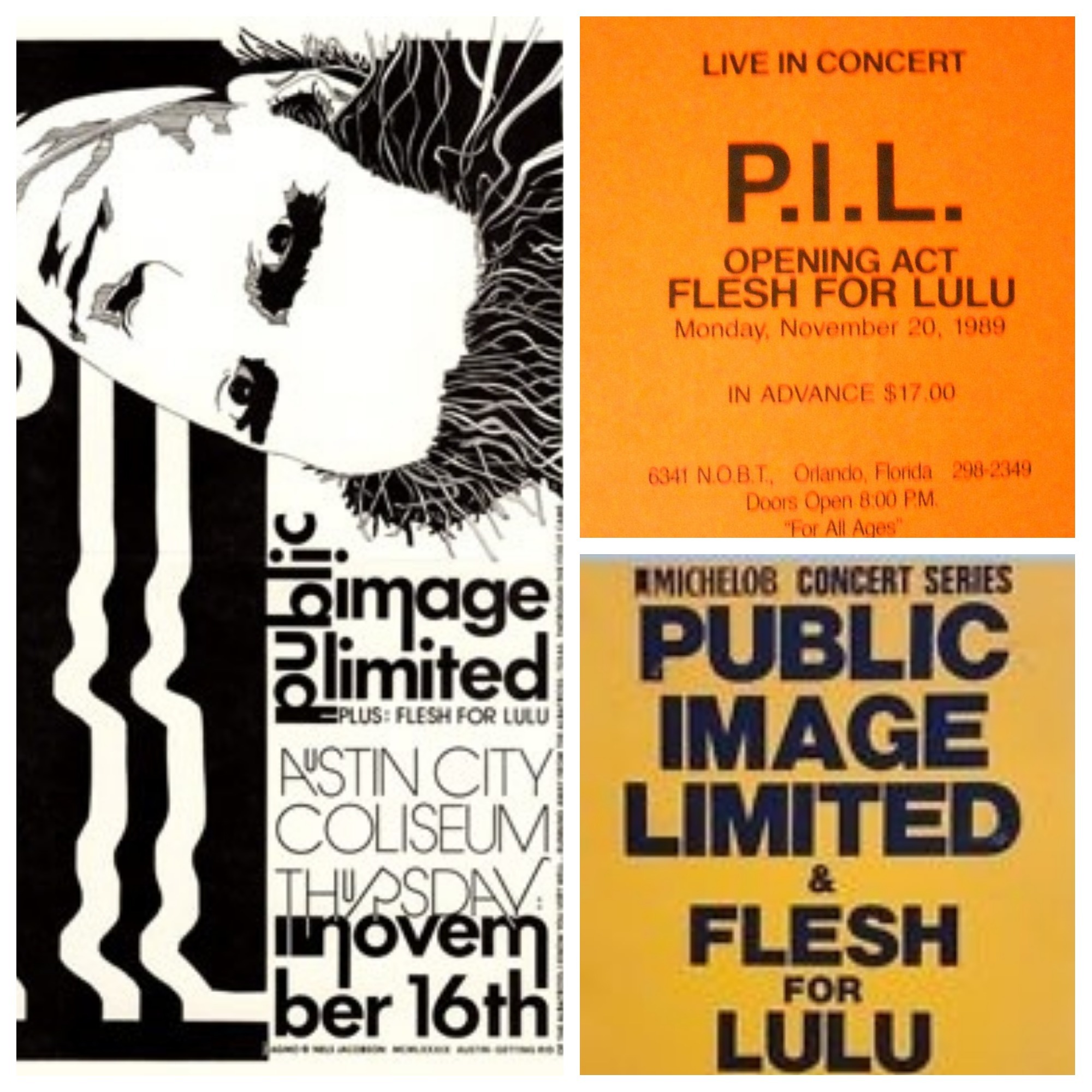

But the story wasn’t quite over. Kev had landed them a massive tour supporting Public Image across the States and Canada.

“I worked my balls off getting this tour together,” says Kevin, “and just as we were about to go out on tour I got a call from Nick.

“Nick went, ‘Yeah Kev, I don’t want to work with you anymore. Or James.’ I was like, ‘Are you kidding?’”

Alright, Kev could sort of see it coming, but still. So they talked for a bit and Kev accepted it was over. “I said, ‘OK, but after the tour, yeah? Let’s go out on a high.’”

But Nick was adamant. He didn’t want to go on tour with Kevin or James. And, Nick said, Rocco felt the same. Their minds were made up.

So Kevin and James were out on the eve of the biggest tour the band had ever done. “I was like, ‘Well, fuck you very much,’” says Kevin.

Rocco doesn’t remember it this way. “I don’t think anyone was sacked,” he says, even when I tell him that Kevin says Nick called him up and fired him over the phone.

“Nah,” says Rocco.

“Yeah,” says James. “He did.”

Rocco: “Did he?”

“Yeah,” says James.

But Rocco still doesn’t think anyone was sacked. Not really. The way he remembers it, they got back from Australia – Rocco, Nick and Del flew to Bangkok for Christmas Eve 1988, went mental, flew back home – and when they’d been back for a bit, Rocco phoned Nick and told him he was leaving. He’d come back and had a good chat with his partner at the time – Cleo Murray, the lead singer of the March Violets – and between them they’d agreed it was time to move on.

When he told him, Nick was shocked, but after a while he rang back and said, “I’m leaving as well. We’ll leave together.”

(The year before he died, Nick told Vive Le Rock this exact story, but the other way around: “We came back to London and I said, ‘I quit’ and Rocco said, ‘I quit as well then’.”)

Rocco and Nick called a meeting in a pub in the West End at 11 in the morning. “I was in at half past 10,” says Rocco, “fucking drinking a whisky before they got there. I was dreading it.” Things had snowballed: suddenly the two of them were carrying on and James and Kevin were out. Rocco tried to keep his head down. “I was like, ‘You know what? Whatever’. We all met. It didn’t even last that long…”

“I was basically sacked from my band,” says James. “The band that I started.”

So it didn’t end particularly amicably, you know. There was a cease and desist order and some legal squabbles. After a while, Kev heard that they’d got new management, a couple of fucking guys, Pushy and Cushy or some shit – Mr. Pushkin and Mr. Cushberger – two American dudes who were like, “Hey, we’re a shit hot management team!” But it was a disaster and after the Public Image tour it all fell to bits.

Both Kevin and James couldn’t help but take a little bit of satisfaction from that.

On one hand, Rocco describes the PiL tour as a bit of a laugh – big venues, great hotels – but the stories from the tour are dark. Nick told Vive Le Rock that one night John Lydon spiked his drink with peyote, and then whispered in his ear all night, tormenting him and turning Nick’s trip bad. There’s another story involving a serious unprovoked assault that I only have anecdotal evidence of.

And then there was the Lydon brawl.

They’re on the PiL tour and Rocco hits it off with PiL guitarist John McGeogh: “a lovely guy. Scottish, always pissed. I used to call him The Chardonnay Kid,” says Rocco. “He’d call your room. [Mimics McGeogh on the phone, in thick Glaswegian] ‘Hey! Ah’m in tha jacuzzi, man! Wi’ a bottle o’ Chardonnaaaay!’ I mean, literally: 9 o’clock in the morning, most mornings, it’s McGeogh, ringing you.”

One particular day, Cleo flew in and that night everyone ended up at a club, sat at the bar. Rocco’s got Lydon on his right and Cleo to his left. Nick’s the other side of Lydon. The house band are playing Flesh For Lulu songs and they ask Rocco to come up and play guitar with them. Afterwards, when he sits down, it feels like Lydon’s a bit weird about it.

Lydon had been bragging about how much he’d spent on this shell suit he was wearing. “He’d bought it in a Hilton over there and it’d cost him 400 bucks,” says Rocco, “for this nylon Adidas thing. Meanwhile, Cleo had bought me this Indian shirt for, like, 130 quid from Kensington market. That was a lot of money in those days.

“Lydon gets this big black marker and goes – bleueurgh! – draws a big black line down my lovely, light blue Indian silk shirt. Like, nice. Well done, mate.

“So I thought, fuck you.”

Rocco was a chainsmoker at the time. He looked Lydon in the eyes, turned the lit end of his Marlboro towards him and – Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! – jabbed it all over his new tracksuit. “I totally ruined it,” he says. “So he takes a swing at me.”

Except Rocco ducks and Lydon hits Cleo, knocking her clean off her chair. Rocco swings at Lydon, and hits him in the neck, knocking him to the floor. “I mean, I can’t fight,” says Rocco, “look at me, but before I can even get down there – I was gonna help him up, to be honest with you – some bloke grabbed me from behind…”

They’re both kicked out of the club and the fight continues out in the street. Lydon had a bodyguard, a big American fucker, but of all the nights, he wasn't there. All Rocco remembers is the two of them ending up in the gutter, Rocco on top, trying to stop Lydon from going mental, basically, and Lydon saying, “Don’t hurt me, I’m your friend!”

The next morning, the phone rings and for once it’s not The Chardonnay Kid, it’s the band, having a right go: “What the fuck are you doing, hitting John Lydon? We’re off the fucking tour!” all that.

Fuck that, says Rocco. We’re only on it because they haven’t sold enough tickets.

They go down to soundcheck. Lydon used to do a soundcheck every day, but on this day he’s not there. They walk in and suddenly PiL stop playing and start cheering and clapping. McGeogh is like: “Fucking well done, it’s about fucking time someone did that.”

It was fine – they were still on the tour.

Lydon didn’t do any soundchecks for the rest of the tour. He kept himself to himself, and at the last show in LA, made his move.

“There was a backstage bit,” says Rocco, “but there was also a backstage of the backstage with a rope across it, so you could go back after a gig and have a line or whatever. So I was back there, doing one, and I turn around and it was him.

“And he went, ‘You do forgive me, don't you?’ I went, ‘Fuck’s sake – of course I do!’ I think he waited because he couldn’t face Cleo. I think he was pretty embarrassed.”

Plastic Fantastic flopped. It came out in the UK four months after the US release, in 1990: the year of Pills 'N Thrills And Bellyaches by the Happy Mondays, Jane’s Addiction’s Ritual De Lo Habitual and Fear Of A Black Planet by Public Enemy.

Plastic Fantastic seemed to belong in a different era. It had cost £400,000 to make. “Put it this way,” says Kevin, “it’s probably part of the reason why we haven’t seen any solid royalties for any of our stuff…”

Derek returned to Peter & The Test Tube Babies’ and later that year, Rocco and Nick popped up on their album of Stock, Aitken & Waterman covers, The Shit Factory, and then faded from view, officially announcing a split sometime in 1992.

“It’s hard to remember,” said Nick, “because the 80s is really trendy now, but at the time if you were a band that was around in the 80s, you were shit on the shoe of fashion and the music industry. We were so fucking unhip all of a sudden. Everyone hated an 80s band.”

Grunge changed the musical landscape yet again. By the mid-90s, alternative rock was big business and Nick and Rocco rallied once again. They dropped the name Flesh For Lulu and put together a band called Gigantic.

“This is where me and Nick fell out a little bit,” says Rocco. “Once Nirvana came along, Nick felt that bands like Flesh For Lulu were redundant. And in the short term we probably were, because those bands – Smashing Pumpkins, Nirvana, Hole, all those – changed everything. So we went through this whole period writing songs, and we knew we could make a really good record, and we’d make it heavier and guitar-y… But Nick wanted to change the name. I was like, ‘Noooo…’”

“We’d done a record that sounded current and we wanted a new start,” said Nick. “It was kind of stupid and insecure. We thought, ‘Let’s get a new bass player and drummer and start again!’ It was a stupid idea, really, because people knew us as Flesh For Lulu. But we changed our name to Gigantic and got signed to Columbia, went to LA with Tim Palmer and did this album and it fucking kicks arse. But we got dropped before it even came out.”

They signed a big record deal with Columbia, played football stadiums with Bush, at the height of their fame, when singer Gavin Rossdale was going out with Gwen Stefani and the papers were all over them. It looked like they were finally on the road to becoming a stadium band. The album got sent out to the press, got good reviews – and then never came out.

The A&R guy who’d signed them, Nick Terzo, had also signed Alice In Chains and the way Nick Marsh remembered it, “the singer in Alice In Chains was shooting a lot of dope and there was trouble between the A&R guy and the head of the label.”

Terzo left and the head of the label said, “Fuck you – and fuck those Limey guys as well…”

Later, says Nick, “We got signed again as Gigantic to Music For Nations and they fucking dropped us before it came out again. So me and Rocco went, ‘Fuck it’.”

The album couldn’t have been more perfectly titled: Disenchanted. Nick and Rocco formed and joined a dozen little bands in the following years before giving up on the dream.

“After getting signed and dropped, signed and dropped, I thought, that’s it, I’ve had my innings,” said Nick. “So me and Rocco went our separate ways for a while.”

After Flesh For Lulu, James Mitchell formed a band where he sung and played guitar. Former Flesh For Lulu manager Peter Webber did a video for one of their songs, but ultimately it didn't happen. James did a course in screenwriting and is now writing his second novel.

Peter Webber became a well-known director, working in film and TV and most famous for his 2003 movie debut, Girl With A Pearl Earring, starring Scarlett Johansson and Colin Firth, which won both Oscars and BAFTAs.

Kevin Mills had a couple of bands right after Flesh for Lulu where he sang and played guitar, and stayed in music for another 12-15 years, composing for film and TV. Today he runs his own Pet Taxi business – taxis that allow you to travel with your pet.

Derek Greening still plays with Peter & The Test Tube Babies and has his own radio show and podcast, Del Strangefish’s Punk Rock Show, on Radio Reverb.

Rocco Barker modelled for Dunhill with Christopher Lee and became the face of a supermarket in Germany. He starred in a reality TV series on Channel 4 called A Place In Spain – Costa Chaos, about him and his then-partner buying a property in Spain. In the Flesh For Lulu years he’d been a compulsive collector of vintage sunglasses. Now he has his own business, turning vintage frames into designer glasses. He also married, and has kids with, one of Nick’s long-term girlfriends – a woman, he says, who once hated him. “The last person I thought I’d end up with…”

The Spirit of Sympathy For The Devil climbed back into bed and pulled a quilt over his head. They were turning Olympic Studios into a cinema and he wasn’t surprised in the slightest.

Nick kept writing songs – not with a rock band in mind; something more intimate – and joined The Urban Voodoo Machine in 2003, filling-in for a gig and staying because he loved it so much. Raucous live shows, great songwriting, a strict dress code – Nick felt right at home. “I’m really only interested in having a good time,” he told me. “For everybody who’s in the band, it’s a party. I predict a lot of touring and shenanigans with this band.”

But he kept his own thing going too. In 2006, he released a solo album A Universe Between Us, a grandly introspective album with shades of John Barry and Scott Walker that really deserved even a fraction of the attention given to similar work at the time by Richard Hawley. It was produced by Katherine Blake – formerly of Miranda Sex Garden and a founding member and Musical Director of the Mediaeval Baebes – and the two became a couple. Nick co-wrote songs for Katherine’s solo album, Midnight Flower, and she appeared on the cover pregnant with the first of their two children. (In October 2015, just months after Nick’s death, they released an album together under the band name From The Deep – a varied album of sultry folk and brooding country featuring both of their haunting, gorgeous voices.)

In 2007, Gigantic’s Disenchanted album was released as a Flesh For Lulu album called Gigantic. In 2009, a new Flesh For Lulu – with Keith McAndrew on bass and Mark Bishop on drums – released a ‘best-of’, with all of the songs re-recorded. “It’s a bit of a middle-finger up to the record industry,” said Nick. “By re-recording the songs, we don't have to pay the labels. Plus, 20 years later, I’m a better singer, a better guitar player, and also the words carry this extra gravitas. You look back and realise what motivated you to write the lyrics, like, ‘Wow, I was some fucked-up kid’, you know what I mean?”

His voice really had gotten better over the years. “Best I ever heard Nick sing was on the Gigantic album,” says Rocco. “Nick used to do this thing, right, where he could split his vocal chords. They wouldn’t be in tune but it was like two people singing, it was bizarre.”

The ‘best of’ album had one new song on it, which was also released as a single: Cold Flame, a song Rocco wrote back in the 80s (“with Nick’s help, of course”). Powered by a riff that’s a kissin’-cousin to the one on Thin Lizzy’s Rosalie, it is classic Flesh For Lulu. Cool, sexy and timeless, it could easily have appeared on any of their first three albums. ‘We’re snatching defeat from the jaws of victory,’ drawled Nick. ‘I’m gonna catch a falling star and set it free/ Just like a setting sun that glows until the end/Oh, we were lovers but we never could be friends’. It was the band’s last release.

Rocco gave up in 2013 and guitarist Will Crewdson replaced him. Crewdson had been a Flesh fan and later he was in the band Rachel Stamp and Gigantic supported them. “I couldn't believe that they were supporting us,” he says. “It didn't seem right at all.”

A friend of Will’s put them in touch with the Goo Goo Dolls and Flesh For Lulu joined their UK tour and played to packed audiences every night, including a night at Hammersmith Apollo.

And they recorded some songs too, says Will. A song called Crazy Eyes – “a very glam, T-Rexy type thing” – and another called Rock’N’Roll Won’t Get You Nowhere that was “almost like a doo-wop punk song. It starts off like something from Grease and then goes into full-on Flesh For Lulu, guitars wailing”. And they re-recorded Dogs, Dogs, Dogs. “As far as I know that was the last thing Nick recorded,” says Will.

Things thawed between James and Kevin and Nick and Rocco. They’d bump into each other around town and occasionally there was talk of getting the original Flesh back together, but it never really suited everybody.

But Nick never quit. One time James posted a link to the John Peel demos on his Facebook page and Nick called him, pissed off: “How dare you do that, James?” he said. “I’m trying to be Mr Rock’n’Roll now! This is destroying my image – I’m trying to get Flesh For Lulu going again!” They had a little spat about it and Nick rang back the next day and said, “I’m so sorry, I don't know what’s got into me. I’m going through a hard time. I was talking out my arse, it’s cool.”

“One of the things I love about him,” says Kevin, “is that he just kept going. That’s what he was born to do. He was born to sing and play, write songs and front a band – and he was great at it.”

In 2014, Nick was diagnosed with mouth and throat cancer. “I had a funny sort of blip in the corner of my mouth,” he said. “Like a grain of rice.” The doctors said it was nothing but he went back and insisted they take another look. “I just knew something was wrong. Gut instinct, you know?” He started writing about his treatments and battle against cancer on his Facebook page. “I didn’t know how else to approach it really,” he said. “I just thought, ‘Here I am’. Facebook is like an open diary if you want it to be.”

So his Facebook friends watched as he "had all my back-teeth on the right hand side removed in order to remove cancerous tissue from my mouth and a section of my forearm – including veins, tendons and skin – transplanted in its stead. The cancer had begun to spread into the lymph-nodes under my jaw, so a massive section of my neck was also dissected and removed. After surgery, I had a six week, intensive course of radiotherapy five days a week accompanied by six courses of chemotherapy. The sixth dose was withheld as there was a strong chance I wouldn't survive it, due to weight-loss and dehydration…”

The NHS oncology teams took special care not to zap his vocal-chords, he said. That throat of his – that golden larynx, the source of his to-die-for voice – was now the thing that was killing him.

In 2015, tests revealed that the cancer was still there and the fight started again. A Flesh For Lulu gig at the Brooklyn Bowl, inside London’s 02 Arena, was scheduled for May but brought forward to March. Backstage, Nick showed us how wide, post-surgery, he could open his mouth (he would have struggled to eat a plum) but it didn’t affect his performance. The gig was a triumph: you couldn’t believe anything other than Nick Marsh was going to beat death.

“We finished with Sleeping Dogs,” says Will Crewdson. “It ends with the line ‘I’m gonna live til the day I die’ and he sung it twice – he’d never done that before.”

"Everyone was like, ‘He’s gonna beat it’ and I knew he wasn’t,” says Rocco. “At the end it was fucking horrible. Fucking awful. I don’t want to go into it.” He tells me about how once, returning home after a hospital visit, his body started to seize as he came out of the tube. By the time he got to his home in Westbourne Park, he couldn't move. “I think it was just shock. I think I went into shock. It was horrible.”

The cancer moved from Nick’s jaw and into his brain. In the last week of his life, friends and family – and fans – turned up at the hospice to say goodbye. He died on 5 June, 2015.

“I still find it really difficult,” says James. “I was angry when he died.” He found himself wandering around his house muttering, ‘fucking Nick’ under his breath. He thought they’d have time to fix things, maybe play together again. Just recently he’d started playing drums again and would definitely have played with Nick, if he’d been up for it.

“I feel embarrassed and regretful that we ended up having a go at each other over our musical capabilities,” he says. “Nick was the only good musician in the band. We weren't good to each other and I find that embarrassing. I wish that hadn't happened.

“And I’m embarrassed about our thirst to be successful,” he says. “It’s stupid – you should just do what you do. I regret that stuff. And I regret Nick not being here.”

“I spent more time with Nick than anybody else on this planet,” says Rocco. “We were inseparable. For years, if you saw Nick, you saw me. If you saw me, you saw Nick. We even lived together – and if we didn't live together, we lived like a street away from each other. It was only the last eight years of his life that I didn’t see him as much.

“I miss him. I miss my mate. I miss him so much. There’s a period where I just couldn't wake up in the morning without thinking about him.”

One day recently, he was alone in his workshop and he decided to put on Big Fun City. Halfway through Baby Hurricane, he switched it off. “I just couldn't listen to it,” he says. “It’s still difficult to come to terms with. I just feel like he’s just gone before his time.”

He gets upset and I apologise for bringing it all up again. “No,” he says, “it’s actually good to talk about it.

“It’s good to be able to talk about it. But it’s fucking hard to accept.”

Ironically, the last time the band were all together was at another funeral in Epping Forest in 2010. Lucy Wisdom had been a friend of the band and ex-girlfriend of both Kevin and Rocco – the woman who saved his life back when he joined Flesh For Lulu and came off heroin.

At Nick’s funeral, the sun shone, jets screamed across the sky and his friends saw him off in style.

The dress code said ‘Dress fabulous’ and they did. It was a thing about Nick. He always looked cool-as-fuck, dressed in vintage suits, great shoes, his hair perfectly sculpted.

“I dunno how you can wear those,” he said to me once.

Wear what?

“Jeans,” he said. “I dunno how anyone can wear jeans.”

Flesh For Lulu’s debut album is out now in a deluxe 2CD edition with bonus tracks, on Caroline records. Many of the pictures in this feature were taken from Flesh For Lulu 1983 -1985, a photobook by Mick Mercer available from Lulu. A second solo album from Nick Marsh will be released later this year.