“It was my own personal hell”: the story of Pearl Jam’s most difficult record as it turns 25

The Seattle rockers’ trickiest album was fraught with writer’s block and drug addiction and it’s not one guitarist Stone Gossard is in a hurry to listen to again.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

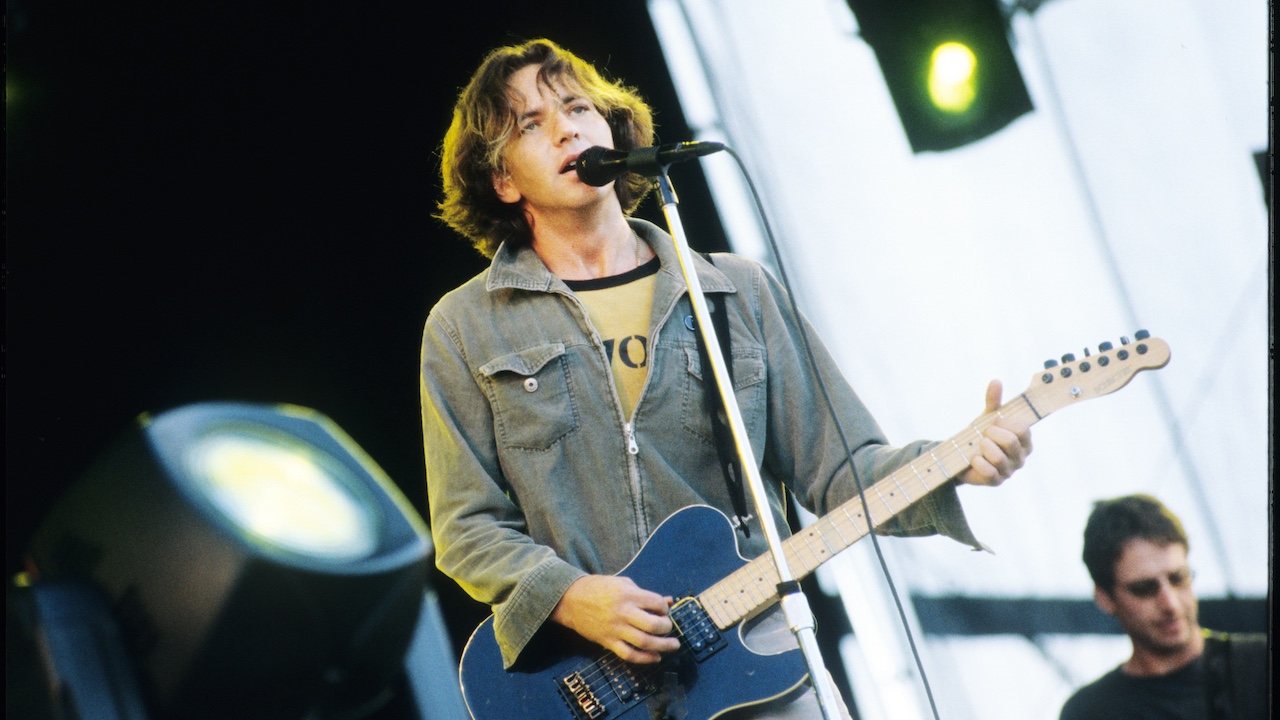

Pearl Jam began the new millennium keen to show that they were not the same band who had helped define the music of the previous decade. Binaural, the Seattle legends’ sixth record, was released in mid-May, 2000, and turns 25 this month. The idea was that it would signify some sort of fresh start for Eddie Vedder & co., more exploratory and experimental than their already-exploratory and experimental previous two albums (No Code and Yield).

They have never been a band who traded happily on past glories, mixing it up each time in the quest to introduce a little fresh magic dust into the equation, and on Binaural the reset was double-pronged. One major difference since Yield was that ex-Soundgarden drummer Matt Cameron was now behind the kit. Another key change was that after working with producer Brendan O’Brien on every album since the all-conquering Vs., they now had a new face manning the mixing desk. Tchad Blake, celebrated for bringing a dynamic sound to records from Tom Waits, Tracey Chapman and more, was on board. His approach to recording was the technique from which the album took its title: binaural recording was a method that used two microphones to create a 3D stereo sound. “Tchad has a very distinctive way of recording the sound of the room,” Eddie Vedder said in the band tome Pearl Jam Twenty. “We were interested in exploring that atmosphere. A lot of the time on Binaural, it’s almost like the listener is there in the room with us.”

That listener might have felt a bit awkward, though. Pearl Jam had a lot to untangle as they got to work in Studio Litho, a recording facility owned by the group’s guitarist Stone Gossard, in Seattle. One major issue was that Vedder was suffering from writer’s block. “I almost went completely crazy,” he told the NYRock website at the time. “I kept changing the lyrics and then changed them again, just to write another version. I ended up with several versions and then used the best and put them together and that worked surprisingly well. But I before I did that, I thought it would never happen, I’d never be able to finish it… It was my own personal hell. I had a great time but at the same time the lyrics just didn’t come together and I was wrecking my head. I still can’t believe that it’s all done and over with, that I finally got all the lyrics together.”

He wasn’t helping himself, he added, by constantly comparing his work to that of his heroes, having recently noticed that his idol Pete Townshend had already written their rock opera Tommy by the time he was Vedder’s age. “That made it much harder to come up with good lyrics,” he said, understandably. “I was always comparing my lyrics to great lyrics. There’s so much junk on the radio that I set myself very high standards.”

He’d also noticed listening to the radio, he explained to Rolling Stone, that there was an alarming amount of Eddie Vedder soundalikes out there on the airwaves. “Last time I listened to the radio, I was like, ‘Who the fuck is this guy and maybe I should call an attorney!’,” he wise-cracked. “It’s kinda funny that you can copyright a note progression but you can’t copyright your voice and the way you sing.”

Vedder’s concerns over his lyrics – and his copycats – weren’t the only thing going awry at Pearl Jam HQ at the time with guitarist Mike McCready mired in prescription drug and health issues. “Binaural is a dark time for me,” he confessed. “I was struggling with Crohn’s disease and struggling with addiction. I was taking pills to take care of that. And then that got out of hand, and it was dark.” McCready would enter rehab for the second time during the recording sessions.

The band found a way to the end, though, creating a collection of songs that pinballed from surging rockers (Breakerfall, God’s Dice, Insignificance), yearning ballads (Light Years), experimental art-rock (Sleight Of Hand, Evacuation) and one ukulele-fuelled ditty (Soon Forget). But still, there were hurdles to get over. There found at the mixing stage that perhaps Blake wasn’t the guy to get the record across the finishing line and turned to their old pal Brendan O’Brien instead. “Tchad had some great ideas, he did a great job on the slow songs,” explained McCready. “But other songs were harder for him, so we called Brendan to remix, to make the songs heavier.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Looking back on the record with a decade and more’s worth of hindsight, guitarist Stone Gossard viewed Binaural as a missed opportunity. “That’s an album I need to listen to in another ten years,” he shrugged. “We weren’t as loose with one another or sharing as well as we usually did. It was our first record with Matt Cameron. He’s a genius, one of the heaviest drummers of all time. It feels like we should have gotten more out of him… We’re never going to remember that record as one of the greats.”

Incidentally, it has been over ten years since Gossard made that comment so, if you’re reading Stone, it’s time to stick on Binaural and see what you make of it, 25 years on…

Niall Doherty is a writer and editor whose work can be found in Classic Rock, The Guardian, Music Week, FourFourTwo, Champions Journal, on Apple Music and more. Formerly the Deputy Editor of Q magazine, he co-runs the music Substack letter The New Cue with fellow former Q colleague Ted Kessler. He is also Reviews Editor at Record Collector. Over the years, he's interviewed some of the world's biggest stars, including Elton John, Coldplay, Radiohead, Liam and Noel Gallagher, Florence + The Machine, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Pearl Jam, Depeche Mode, Robert Plant and more.