“It felt like the best thing we’d ever done. I was shocked when it wasn’t received well. The record company definitely didn’t like it”: Inspired by King Crimson, this 80s band pioneered a new kind of rock – and paid the price

Their bassist quit, then the band split after one more record. Nearly four decades on, their ambitious post rock album is regarded as a masterpiece

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In 2019 former Talk Talk bassist Paul Webb told Prog about his bewilderment when the band’s fourth album, 1988’s ambitious Spirit Of Eden, turned out to be a commercial failure – despite feeling like their best-ever work. He also explained how it felt to live in a world without ex bandmate Mark Hollis, who’d died weeks before Webb released his second Rustin Man record, Drift Code.

Mark Hollis’ total retreat from the music industry to spend more time with his family seemed a bold and perplexing move to many – but it made sense to Paul Webb, his former bandmate in Talk Talk.

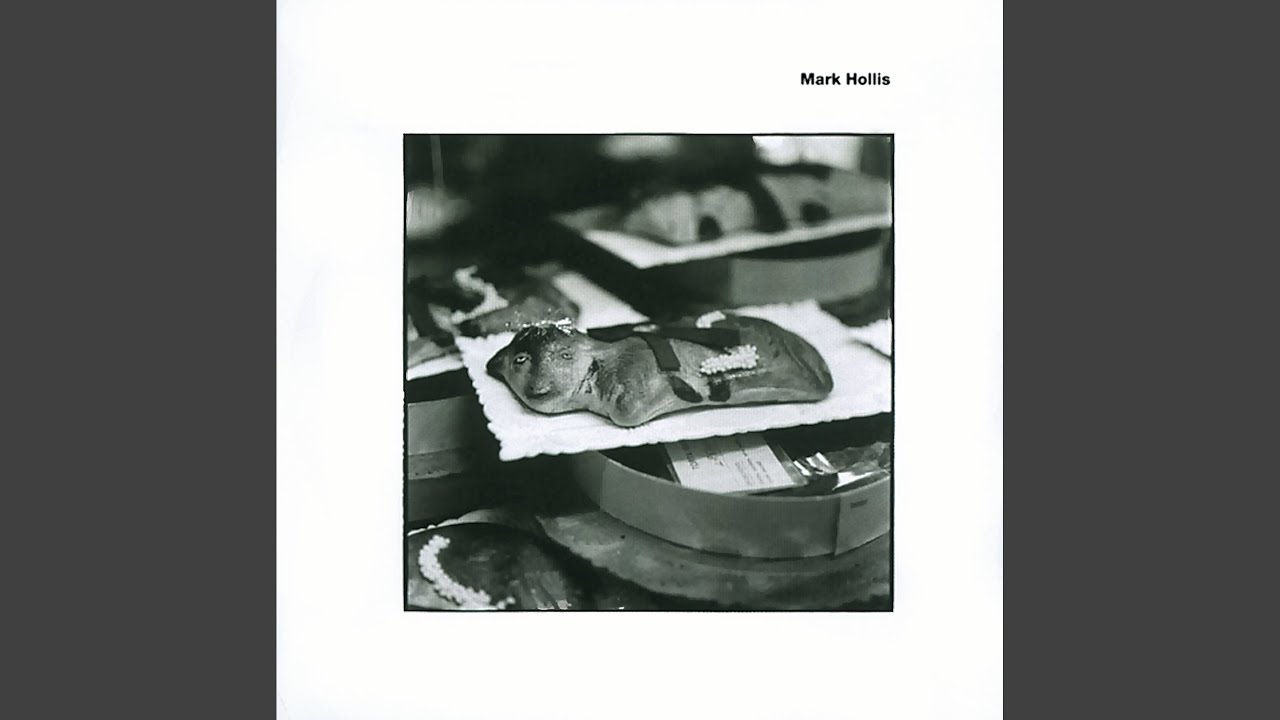

Hollis released a solitary self-titled solo record in 1998, seven years after Talk Talk’s demise. Then he quietly left the world of music altogether, releasing no further artistic statements before his death from cancer in 2019.

“Knowing him, I’m not surprised at what he did,” Webb says. “He always had control of his life and how he wanted to live it. He was so passionate about music, so intense – but music took it out of him as well. He’d done what he’d set out to do. I think he knew when to stop.”

Hollis died a few weeks after Webb had released Drift Code, his second solo album under the Rustin Man banner. “I was very saddened and very shocked,” the bassist said. “The world does feel different without him here. The outpouring of love for him and the band – that was overwhelming.”

He remembers: “Mark was like a mentor; he inspired me to go on and do what I did. He’d play me records like Miles Davis’ Sketches Of Spain and Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, and tell me what he loved about them.

“Mark liked Traffic, Can and Weather Report. He was also into King Crimson, as was I; all that Mellotron! In The Court Of The Crimson King was a big reference point for us.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

He finds it difficult to define how or why Talk Talk became such an influential band. But he can’t forget how special their fourth album, 1988’s Spirit Of Eden, felt to him – even though it turned out to be a commercial failure.

The band proved their art rock credentials, and are credited with pioneering post rock, with a record that was tracked in almost complete darkness, then digitally reworked from endless multi-genre jamming.

“From the minute I heard the demos from Mark, [producer] Tim Friese-Greene and [drummer] Lee Harris, I absolutely loved it; there was such a feeling of space in it. When the mix was finished, it felt like the best thing we’d ever done.

“I was so confident that everybody outside the studio would think the same. I was shocked that it wasn’t received that well when it was released. The record company definitely didn’t like it.”

While Spirit Of Eden didn’t do well at the time, its value has been reinterpreted through the years. But it was the last album Webb made with Talk Talk, who themselves only released on more record – 1991’s Laughing Stock – before splitting.

He went on to launch Rustin Man’s first album, Out Of Season, in 2002, featuring Beth Gibbons of Portishead, and also worked again with Harris in .O.rang.

With Drift Code – the first time his own vocals have taken centre stage –Webb says he’s finally found his own voice. “You know what, I think I’m just a late developer!” he says. “It’s just taken me all this time to find my feet.

“I’ve experimented with singing on a personal level, but it feels claustrophobic to me. Earnestness is a very hard thing to portray when you’re singing. Mark and Beth have it; they’re both pouring their hearts out.

“But for me, it’s more about Tom Waits and David Bowie. It’s about storytelling. It’s the same as going to the theatre and seeing a really strong performance – but when the actors walk off stage, they’re back in their lives again. I think of it like that.”

Joe is a regular contributor to Prog. He also writes for Electronic Sound, The Quietus, and Shindig!, specialising in leftfield psych/prog/rock, retro futurism, and the underground sounds of the 1970s. His work has also appeared in The Guardian, MOJO, and Rock & Folk. Joe is the author of the acclaimed Hawkwind biographyDays Of The Underground (2020). He’s on Twitter and Facebook, and his website is https://www.daysoftheunderground.com/.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Talk Talk - I Believe in You (Official Video) [HD Upgrade] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/AD8M_HVauls/maxresdefault.jpg)