“The bassist was found with serious wounds, screaming that Vander had caused him to tear his own chest open”: The mystery and mythology of Magma founder Christian Vander

Trying to unravel the mind of Christian Vander, the enigmatic leader of Magma, can almost be as difficult as trying to unravel the band’s philosophies and own Kobaïan language, as Prog originally explored in 2009.

Christian Vander is one of the most important musicians and composers of the 20th and 21st centuries, but I’m guessing that only a small minority of you reading this will be aware of this. Remember how you felt like an outsider at school because you were one of only maybe 10 kids who were into Yes? Well, Magma fans were in an even smaller sub-set than that, but God – were (and are they) fanatical.

If there’s one thing that people know about Magma it’s that 80s snooker ace Steve Davis promoted a London show by them. For Davis, an unashamed prog and jazz rock fan, Magma were like a visitation from beyond. “It was at London’s Chalk Farm Roundhouse, where I’d gone to watch the support act, Isotope. I was 17,” he told the Guardian.

“I had planned to go home before Magma came on but I hung around and had the most musically life-changing experience of my life. I came out in shock; they blew me away. If I had a time machine and could go back to relive one day of my life, it would be that one.

“They’re the musical equivalent of Marmite – you either like them or you don’t. They were a 70s phenomenon but a bit too far-out for most people, even if you liked progressive music. I didn’t dare put them on the communal record player at sixth form because they’d have been booed off. Maybe it’s because they were French.”

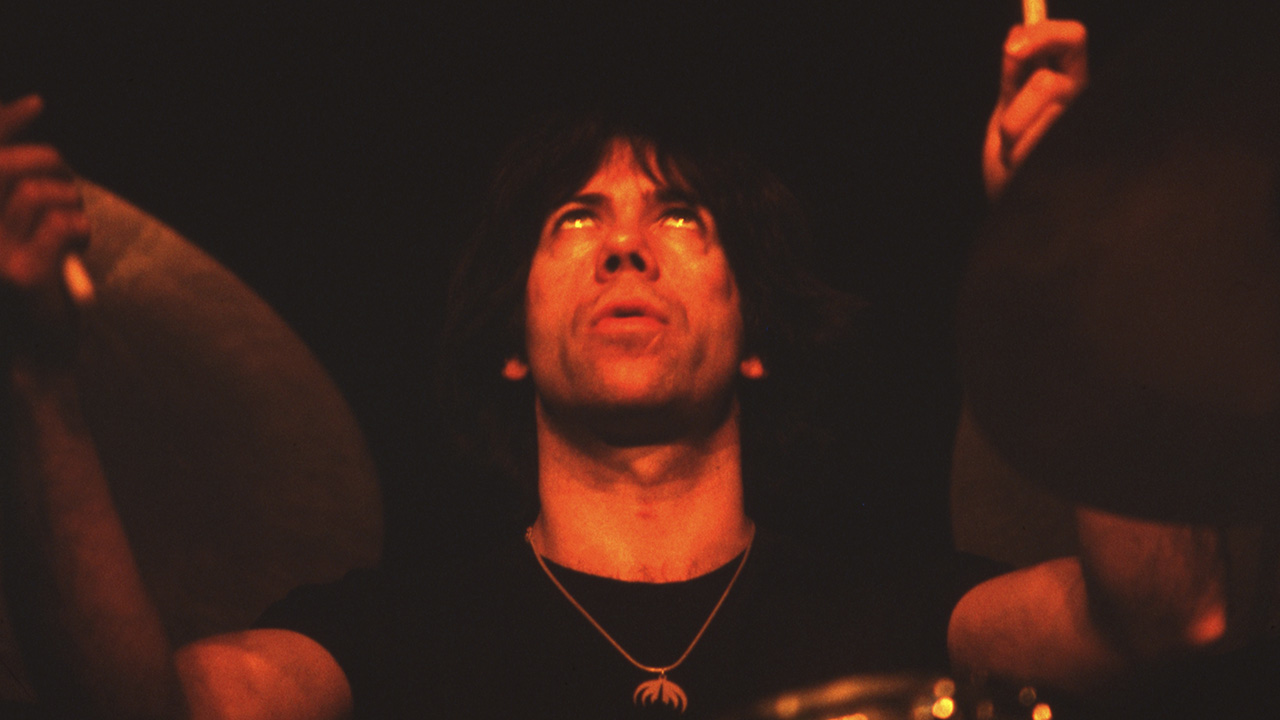

Magma were one of those bands that you knew you just had to hear as soon as you looked at them. In the early photos, they posed unsmiling, wearing black polo-necks with metallic medallions of their distinctive logo on their chests. You’d believe it if you were told they were members of some wacko Satanic cult.

And you’d definitely believe that the man in the centre of the picture, Christian Vander – with that Robin Hood pageboy haircut, that mirthless smile and those Charlie Manson eyes – was the maximum leader.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

And if you were told that they were France’s most left-field jazz rock ensemble whose music synthesised the cosmic yearnings of John Coltrane with the vision of Wagner? Oh, you definitely would believe it: those ‘fuck you’ shots of Magma in flared jumpsuits tell you almost as much about them as their music. Most bands want to have some hits, sleep with a few groupies and get a bit wasted. Magma looked like they wanted to cleanse the stain of humanity from the universe and fuse their souls with the cosmic supreme being.

Vander saw the future of Earth looked bleak: industrial pollution and overpopulation were the scary ideas of the day, which he wove into a vast operatic song cycle

Christian Vander grew up in the French jazz scene and claims that he decided – aged 3 – that he’d become a musician. His stepfather was jazz pianist Maurice Vander, who’d played with the likes of Stéphane Grappelli. Through his mother he met Billie Holliday, Chet Baker and drummer Elvin Jones, who played with John Coltrane. Vander learned drums from Jones and Baker gave him his first kit. By the time he was in his 20s Vander was one of France’s best-regarded sticksmen.

When Coltrane died in 1967, Vander was profoundly affected. Coltrane’s music had been special to him. It reached beyond the confines of jazz. It was profound music, even. Some might say holy music. Vander too wanted to create something that defied genres and boundaries, something that was spiritual, healing and searching in the way that Coltrane had been. To this end, in 1969 he formed Magma.

“The year John Coltrane died, it seemed to me that afterwards it was as though music had to try to start all over again,” he told The Wire in 1995. “Someone had to pick up the pieces; go on searching in the way that he had. Nobody could match him, but people could pick up the flame. It was almost impossible for anyone to do anything new after Coltrane, but you had to try to find other new directions. So that’s what I tried to do with Magma.”

Vander claims he wasn’t so much the creator of the music as its conduit. He once said: “I started Magma because the music had to come out. I would call it a revelation. The music came out of me naturally, without the need to compose it. It came out through me, but it could easily have been someone else.”

Magma became a vehicle for his huge spiritual visionary concept about the future of the Earth, humanity and our place in the cosmos. Although he was never political per se, in the late 60s the first stirrings of what would later grow into the green movement could be seen in Europe and the US.

Vander saw that the future of the Earth looked bleak: industrial pollution and overpopulation were the scary ideas of the day which he took and wove into a vast operatic song cycle called Theusz Hamtaahk, or Time Of Hatred. The first self-titled album, recorded and released in 1970, tells the story of the future when things have gone beyond even the bleakest predictions.

A small group of dissidents escape Earth in a private spaceship and find a colony on the distant world of Kobaïa. There they work out a new, more enlightened way of life, working in harmony with nature and the cosmic force of the universe.

Some years later an Earth ship in trouble lands on Kobaïa. The crew are impressed by what they see and persuade Kobaïan missionaries to return with them to tell the Earth people about what they have achieved.

The second album, 1001 ̊ Centigrades, released in 1971, tells of the arrival of the Kobaïans with their message of peace and love. But the Earth authorities don’t like what they hear and imprison the missionaries, sparking off a war between Earth and Kobaïa.

Vander commands enormous respect with everyone who’s worked with him, but the impression is that it’s bloody difficult to work with him

Kobaïa gives Earth an ultimatum: release them or they will unleash their ultimate weapon, the Mekanïk Destructïw Kommandöh. The Kobaïans escape, vowing never to return – but some Earth people have heard their message and remember their visit.

The third part of Theusz Hamtaahk is about the prophet Nëbehr Gudahtt, who remembers the message of the Kobaïans and preaches that in order to save itself, humanity must seek self- purification and communion with the supreme being, the Kreuhn Kohrman. Naturally this pisses everyone off and they form an angry mob, marching off to lynch Nëbehr Gudahtt.

But en route they all miraculously see the light and accept the truth of his message. Then after a bit more marching and singing hymns of exorcism, they commit mass suicide, becoming transformed and purified and melding into the substance of the universe.

This was the band’s incredible third album, Mekanïk Destructïw Kommandöh, released in 1973. It was apocalyptic music with a story that apparently connected all of Magma’s songs. And for these songs to work, existing languages such as French or English were inadequate: Vander created his own phonetic umlaut-laden language to fit his cosmology. Kobaïan sounded like gutteral German or Serbo-Croat.

This and its equally brilliant successor, Köhntarkösz, were not released on some weirdo European indie label: they came out on A&M, making them labelmates with Peter Frampton and The Carpenters. Both LPs were produced by former Rolling Stones and Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky, a supporter of the band almost since their inception.

Vander composed the words and the music at the same time, the lyrics seeming to flow as he wrote. ‘Kobaïa’ was the first word uttered in this new language. Vander and singer Klaus Blasquiz took the main vocal parts; Blasquiz sounded genuinely demented, while Vander was capable of sounding like Hitler working himself into a lather.

Although as a visionary artist and a gifted musician Vander commands enormous respect with everyone who’s worked with him, the impression from outside is that it’s bloody difficult to work with him. Ego clashes were inevitable – most famously with bassist Jannik Top, who was part of the line-up from 1973 until 1978.

In his book Repossessed, Julian Cope recounts a story told by Martin Cole, who worked with Magma’s management. “The original group had come to a stunning and savage conclusion in Spain. Vander had rented a hilltop castle for his own uses, which had annoyed Top’s ego. He rented a similar place within sight of Vander and the two proceeded to wage magic war upon one another.

“Martin ended driving from one castle to another, trying to patch the band up, only to discover Jannik Top with serious chest wounds, screaming that Vander had caused him to tear his own chest open.”

Top – who has subsequently played with Bonnie Tyler, Eurythmics and Celine Dion – puts his departure from Magma down to youthful inexperience rather than black magic, though he’s avoided taking part in any reunions despite regular invitations to do so.

The meaning of the words are known only to Vander and God, but you can almost create your own story from the barrage of syllables

One of the astonishing things about Vander is that, through many incarnations of Magma and through many other projects – film music, children’s music, bands where he has played as merely a drummer – he is still refining and honing the visionary concept that possessed him back in ’69. Like Wagner, whose music was also hugely influential to him, everything is connected in a massive cycle.

What’s more, Vander has actually spawned an entire genre. Zeuhl – which means ‘cosmic music’ in Kobaïan – is a rich prog sub-genre. Former Magma members formed bands like Weidorje, featuring keyboard player Patrick Gauthier and Bernard Paganotti (Top’s replacement). They paid a sort of homage to their former boss then disappeared without trace. Belgium’s Univers Zero have always been a sort of ‘brother’ band to Magma, as have France’s Art Zoyd.

Top himself formed The Utopic Sporadic Orchestra, who performed De Futura, the epic song that he composed for Magma’s 1976 album Üdü Wüdü. Current Zeuhl prime movers include Japan’s enigmatic Magma-influenced Koenji Hyakkei and the UK’s Guapo. Vander acknowledges the existence of these bands while never admitting that he’s listened to them.

As you have probably gathered, Vander is a bit of a riddle as befits any genius composer. Although he is hardly a recluse, separating truth from myth can be a tricky business because he doesn’t really give much away. He only really seems comfortable when discussing music; and it is through the music that he speaks.

Despite the fact that the meaning of the words are known only to Vander and to God, you can almost create your own story from the barrage of syllables. Like Coltrane or Stravinsky or Wagner, his music can raise you higher than the angels. But it can also take you on a swift tour of Hell.

Magma celebrate their 55th anniversary in 2024 and future plans may or may not include an 800-plus page book of philosophy and an orchestral version of Theusz Hamtaahk. Magma and Vander continue to perform and released the excellent Zëss in 2019, followed by Kãrtëhl in 2022. Hopefully the universe is composing more cosmic music for Vander to channel.

Allan McLachlan spent the late 70s studying politics at Strathclyde University and cut his teeth as a journalist in the west of Scotland on arts and culture magazines. He moved to London in the late 80s and started his life-long love affair with the metropolitan district as Music Editor on City Limits magazine. Following a brief period as News Editor on Sounds, he went freelance and then scored the high-profile gig of News Editor at NME. Quickly making his mark, he adopted the nom de plume Tommy Udo. He moved onto the NME's website, then Xfm online before his eventual longer-term tenure on Metal Hammer and associated magazines. He wrote biographies of Nine Inch Nails and Charles Manson. A devotee of Asian cinema, Tommy was an expert on 'Beat' Takeshi Kitano and co-wrote an English language biography on the Japanese actor and director. He died in 2019.