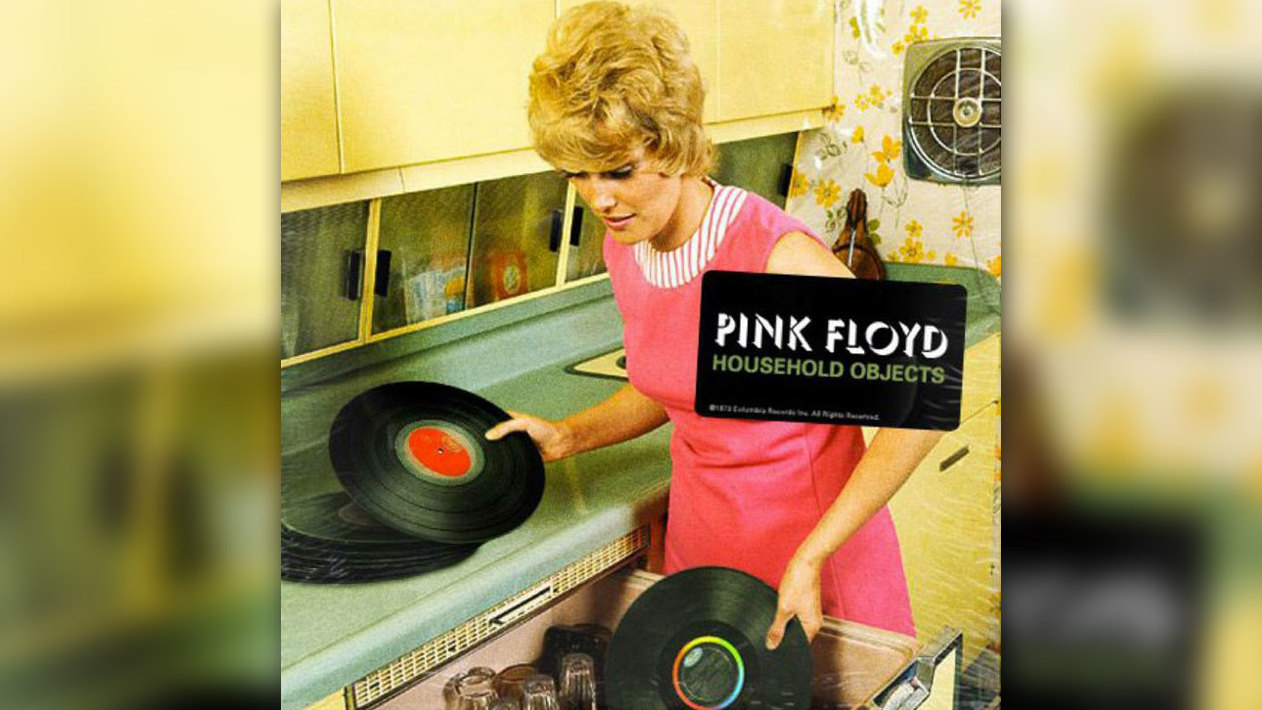

“The sounds of plucked elastic bands and scraping broomsticks are the last hurrah for the old Pink Floyd”: Household Objects, the lost album that nearly followed Dark Side

For over three decades, a two-minute clip of tuned wine glasses was the only sign of a project begun in 1980 and finally abandoned four years later

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

When The Dark Side Of The Moon became an international hit, Pink Floyd’s career path changed forever; and while the change was to deliver much more world-class music, it marked the end of their initial experimental era. This, an incredibly clever concept with the working title Household Objects was abandoned, with only a few minutes surviving to hint at what could have been. Prog told the story in 2016.

Pink Floyd’s 1975 album Wish You Were Here is filled with sounds easily missed by even the most dedicated listener.

There’s jazz virtuoso Stéphane Grappelli playing faint violin on the title track, and the refrain from Floyd’s 1967 hit See Emily Play on Shine On You Crazy Diamond Part IX. The first sound heard on the album is an eerie drone created by fingers running around the rims of wine glasses, each filled with varying amounts of liquid to create different notes.

For more than 30 years the ‘tuned’ wine glasses were all that remained from Household Objects, the working title for a Floyd album started in 1970 and abandoned for good in ’74. In 1973 The Dark Side Of The Moon’s deft mix of hi-fi-friendly sound effects and FM rock turned Pink Floyd into a top-five band in Britain, Europe and, crucially, America. Before that, though, they were a very different proposition.

The Household Objects idea was raised in 1969, when Floyd began performing a new composition, Work, that involved sawing wood and boiling kettles on stage. A year later they released Atom Heart Mother, an album that included the track Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast, featuring the sound of roadie Alan Styles frying eggs and bacon before ending with the hypnotic sound of a dripping tap. Atom Heart Mother was a UK No.1 hit. But, as drummer Nick Mason admitted, “We were still looking for a coherent direction.”

When Floyd reconvened at Abbey Road Studios in January 1971 they were still looking for that direction. Their immediate solution was to dispense with conventional instruments and bring ‘found’ sounds of the kind they used on Work and Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast to the fore.

John Leckie would go on to produce Muse’s Showbiz and Origin Of Symmetry. In 1971 he was a 22-year-old Abbey Road tape operator assigned to record Floyd’s new music. “They spent days working on what people now call Household Objects,” Leckie told this writer in 2006. “They were making chords up from the tapping of beer bottles, tearing newspapers to get a rhythm, and letting off aerosol cans to get a hi-hat sound.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The ideas were catalogued, before the group decamped to George Martin’s Air Studios. They then had a change of heart and returned to conventional instruments for what became their next album, Meddle. Although it utilised some sound effects, the torn newspapers and tapped bottles remained unused.

It would be more than two years before Pink Floyd went back to the Household Objects idea. By then The Dark Side Of The Moon had topped the UK and US charts. But when Floyd reassembled to start work on a follow-up in late 1973 they were in trouble. “We didn’t have an idea between us,” said Mason.

After making the most accessible album of their career, the band’s contrary solution to their writer’s block was to reprise Household Objects. Weeks were spent with engineer Alan Parsons at Abbey Road, creating a percussive rhythm by scraping a witch’s broomstick on the floor or hitting a piece of wood with an axe, and twanging elastic bands stretched between matchsticks.

“I’ve always felt that the differentiation between a sound effect and music is all a load of shit,” bassist/songwriter Roger Waters told Zigzag magazine at the time. “Whether you make a sound on a guitar or a water tap is irrelevant.” Waters insisted that Floyd’s new music, using “bottles, knives and felling axes is turning into a really nice piece”.

By the end of the year, though, he’d changed his mind. Mason has since suggested that Household Objects was a “delaying tactic” in the absence of any new songs. Certainly once Waters had conceived the idea of making an album about absence – the absence of troubled founder member Syd Barrett; the absence of Waters’s soon-to-be ex-wife; and what he regarded as the absence of commitment from his bandmates – the Wish You Were Here album fell into place and Household Objects was forgotten. Although not everyone was happy with this decision. “I was rather disappointed it never came to anything,” said Parsons.

In 2011, Floyd released extended versions of Dark Side and Wish You Were Here. The latter now included the original tuned wine glasses track, and the new Dark Side contained another extract from Household Objects: The Hard Way – three minutes of what may or may not have been torn newspapers in place of drums and what sounds like plucked elastic bands in place of a bass. But the melodic refrain that cuts through several seconds in is pure melancholy Floyd. Fans had waited decades to hear this stuff. The band themselves quickly pointed out that nowadays you could make these sounds in an afternoon on a synthesiser or programmer.

You can understand their reluctance to attach much importance to Household Objects now. After all, The Dark Side Of The Moon turned 20-something ennui and navel-gazing into big business, and Floyd rightly never looked back again. But the sounds of these plucked elastic bands and scraping broomsticks are the last hurrah for the old Pink Floyd; the one that was young, silly and experimental. “It seemed like a good idea at the time,” said Roger Waters. It was, and it still is.

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.