“Ray visited him just before he died and apologised for putting him at the centre of the story”: It took five decades for the Kinks’ Arthur to come of age

The 1969 empire-themed concept album, a commercial flop at the time, is perfectly suited to the current political climate

Although it was a commercial flop at the time, The Kinks had already dipped their toes in the water of concept albums with their excellent, Britpop-influencing Little England commentary The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society in 1968. With Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire), released the following year, the group flung themselves in the deep end with the most ambitious record of their career.

Ray Davies often found source material in his family life and north London neighbourhood, and this time around was no different. Ray’s much older sister Rose had emigrated to Australia in 1964 under the government’s Ten Pound Poms scheme and Ray had been pining for her and her avuncular husband Arthur since.

Granada TV approached with a commission for an ‘experimental’ programme collaboration with playwright Julian Mitchell. Ray had an idea that centred around a salt-of-the-earth carpet layer, and his existential crisis within a post-war Britain that didn’t look after people of his age, or ilk, any more. Arthur the rock musical (or “pop documentary”, as Ray calls it now), loosely themed on his brother-in-law’s life, was conceived.

Causing a little consternation, long-time Kinks bassist Pete Quaife had left, but the line-up of lyricist/vocalist (and guitar/keyboardist) Ray, his brother Dave (vocals/guitar), mainstay drummer Mick Avory and new bass player John Dalton began the recording process at Ray’s manor in Borehamwood in May 1969.

The songs ranged from celebrating the England Arthur grew up in (Victoria and Young And Innocent Days) to going to war (Mr Churchill Says), the death of his brother in battle (Yes Sir, No Sir) and the dangle of the Utopian carrot for emigration in Australia.

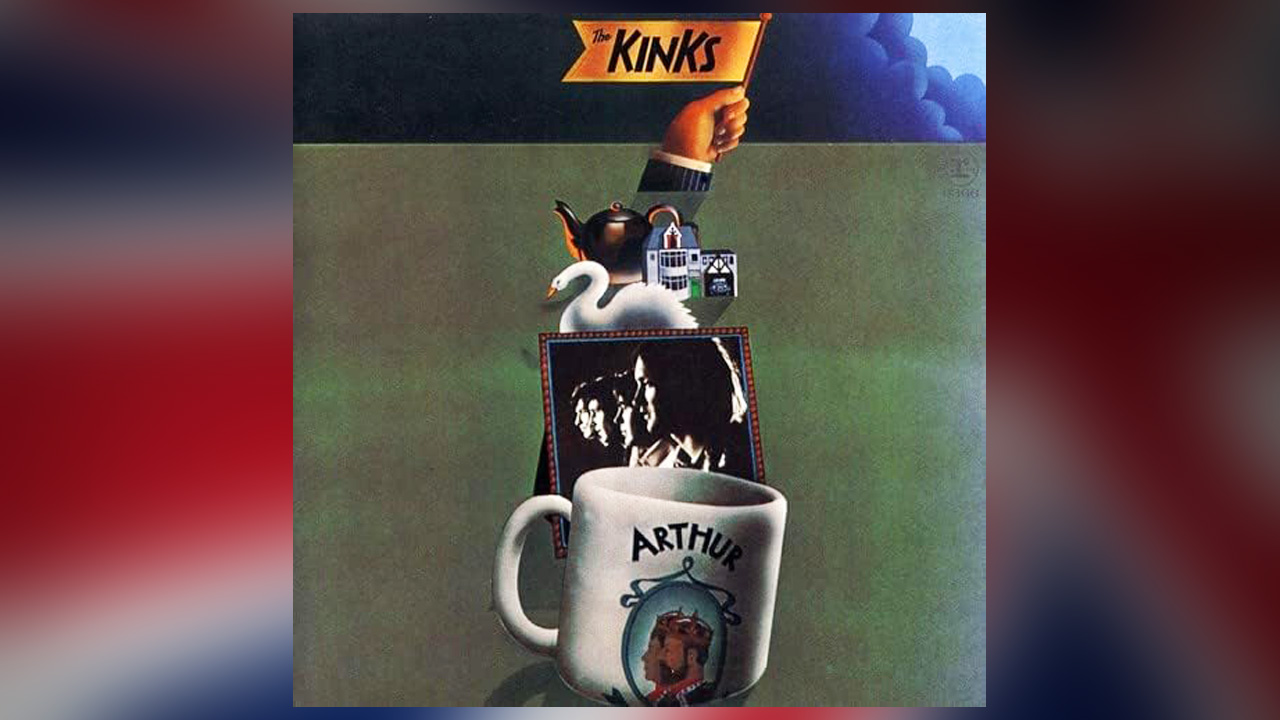

The sleeve, by Bob Lawrie, was all flag-waving, 1911 Coronation cup nostalgia with a Terry Gilliam-esque visual flair and a massive cartoon kangaroo in boxing gloves in the gatefold’s centre. Musically, tropes from Village Green and Something Else remained, with music hall, brass bands and baroque pop mixed with strings, late-60s shaggy rock and Ray’s wry observations.

Two tracks reign: Australia, a jaunty marketing jingle turned into a wonderfully loose jazz-jam, and the melancholic, misguided Englishman’s-home-is-his-castle metamorphic suite Shangri-La.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The album was released to acclaim but low sales; the TV show was pulled due to lack of finance — and the band had been beaten to the rock-musical by The Who’s Tommy.

Oddly, Arthur’s time seems to be now, 50 years on, perfectly suited to Brexit and an era of broken governmental promises. It has finally debuted as a play on BBC Radio 4 as well. And the real Arthur? Ray visited him just before he died, and apologised for putting him at the centre of the story. It was fine — Arthur was flattered. How could you not be?

Jo is a journalist, podcaster, event host and music industry lecturer who joined Kerrang! in 1999 and then the dark side – Prog – a decade later as Deputy Editor. Jo's had tea with Robert Fripp, touched Ian Anderson's favourite flute (!) and asked Suzi Quatro what one wears under a leather catsuit. Jo is now Associate Editor of Prog, and a regular contributor to Classic Rock. She continues to spread the experimental and psychedelic music-based word amid unsuspecting students at BIMM Institute London and can be occasionally heard polluting the BBC Radio airwaves as a pop and rock pundit. Steven Wilson still owes her £3, which he borrowed to pay for parking before a King Crimson show in Aylesbury.