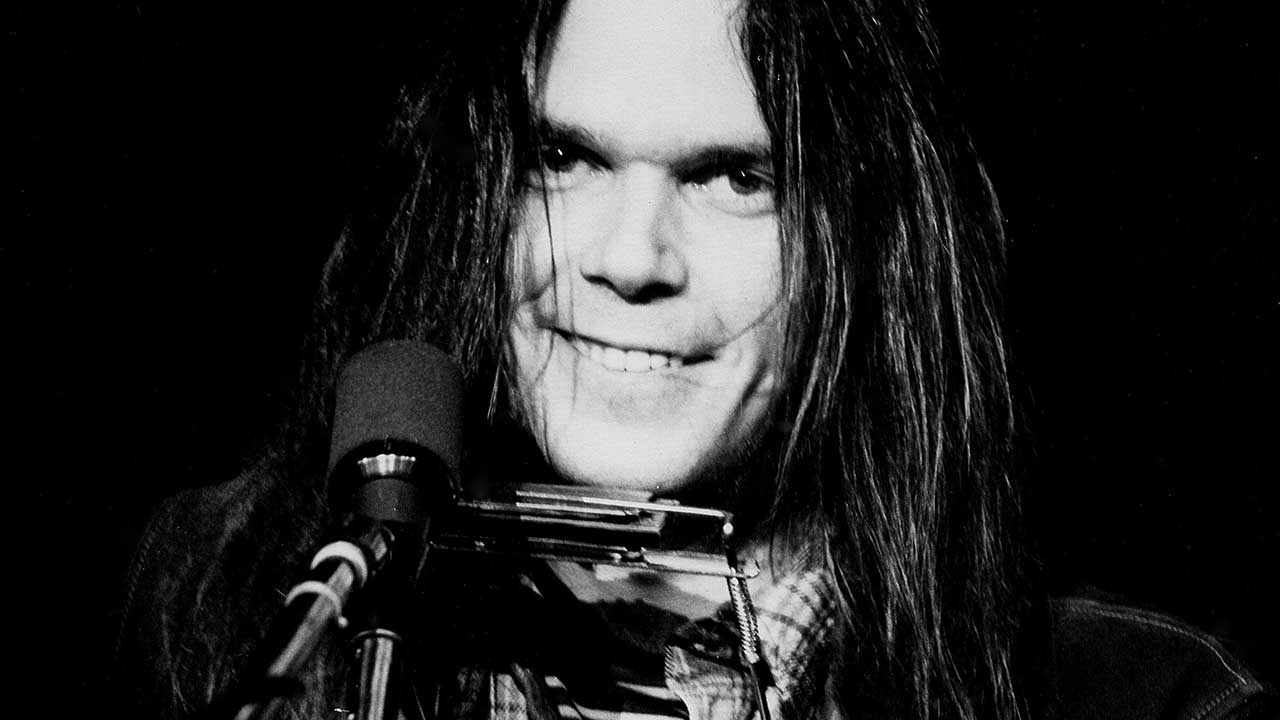

Injury and intrigue: The story of Harvest, the album Neil Young loved then came to hate

With its recording set against a background of drugs and pain, yet written by an “in love and on-top-of-the-world-type guy”, perhaps it’s no surprise that Neil Young’s Harvest divides opinion so greatly

In 1972, Neil Young released his fourth and what became his highest-charting album: Harvest. Acoustic – except for two tracks – out of necessity, because of a back injury that required surgery, it took him an entire year to finish, recorded piecemeal in between tours, hospital stays, surgery recuperations and a high-profile romance that would lead to his first child.

At one point Young called Harvest his “finest album”; then, in 1977, he derided it in the liner notes of Decades, his retrospective collection, all but dismissing it as an MOR aberration.

Forty years later, Harvest continues to confound critics and fans alike. It earned Young his only No.1 record, with the single Heart Of Gold, a song that continues to live on, sung at countless weddings and funerals, and covered by artists as diverse as Zakk Wylde, Boney M, Johnny Cash, Jimmy Buffett and even Young’s Farm Aid partners Willie Nelson and Dave Matthews.

Heart Of Gold was on the soundtrack of the 2010 film Eat Love Pray, and was even referenced by Lady Gaga in You And I, in the deathless line ‘On my birthday you sang me A Heart Of Gold/With a guitar humming and no clothes.’

No matter what you think of Neil Young, or of Harvest, you can’t deny that there has always been something a little prescient and otherworldly about the musician. How else can you explain how Buffalo Springfield came into being – all the members just happened to be stuck in the same LA traffic jam – in a moment that seemed to momentarily subvert the law of physics and geography to make musical history.

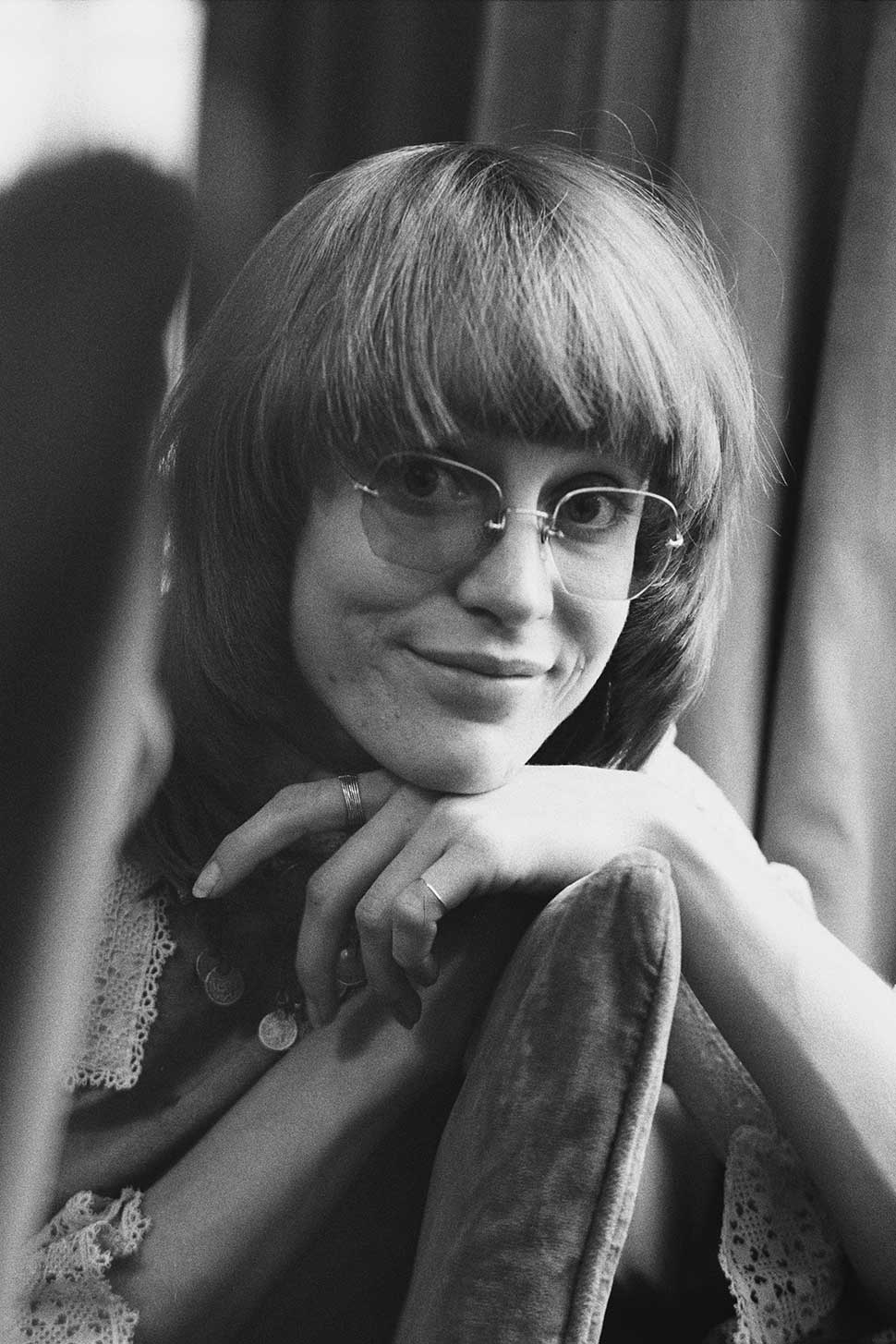

Continuing along those same kinetic ley lines, it’s conceivable to blame Harvest on Neil Young’s former roadie Guillermo Giachetti. In fact, it wouldn’t even be a stretch to say that if Giachetti hadn’t been such a movie buff, Harvest might not have been made. After being awestruck by Carrie Snodgress’s performance in Diary Of A Mad Housewife, the roadie convinced his boss to see it with him while they were on the road in Washington, DC in December 1970.

In the darkened theatre, Young was equally taken with the slight, winsome actress with the throaty voice, and upon his return to California he did some fact finding. As providence would have it – always a big force in Young’s life – Snodgress happened to be performing in a stage production of Rosebloom at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Young dispatched Giachetti and his roadie compatriot Bruce Berry to go backstage at the theatre and check her out. She passed their high scrutiny and they left her a note. The next day, the Academy Award-nominated actress saw a note on her dressing room table that simply read: “Call Neil Young”.

The ironic thing was that she didn’t even know who Young was, which certainly had to be of no small appeal for the soon-to-be-iconic singer-songwriter. After her roommate filled her in, Snodgress called Young and arranged to meet him the next month.

That fateful first date took place in Young’s room at the Chateau Marmont, one of Hollywood’s more infamous hotels, as renowned for its posh European hospitality as for the rollcall of long-time residents like Johnny Depp and Keanu Reeves. John Frusciante lived there after ghosts told him to quit the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and several of the members of Led Zeppelin rode their motorcycles through the lobby to the sound of cheering guests.

But it wasn’t the quaintly appointed lobby, the high tea or the exalted guests – after all, Snodgress was a two-time Golden Globe winner and an Academy Award nominee – or even the fact that Young was wearing a neck brace and confined to a hospital bed that the late actress recalled. Rather, it was the drugs they smoked. This might help to explain their relationship, being that it truly was founded on his illusion of her on the big screen, and perhaps the pills that he was taking to alleviate the pain of his debilitating back injury.

“That Panama Red! Jesus, that was strong pot. I got about halfway home and had to pull over and go to sleep. I got lost going home,” Snodgress told Young biographer Jimmy McDonough.

As for Neil, he fell in love with the actress, arranging for a second date before the evening was over, then checking himself into a hospital the next morning for the excruciating back pain that would require surgery just eight months later. But not before he began sketching out ideas for a suite of songs inspired by Snodgress.

Within the month he had already written A Man Needs A Maid and Heart Of Gold, playing them on piano as one conjoined piece for the first time on January 10, 1971, at the University of Oregon; and then again at Toronto’s Massey Hall, the performance that’s captured on the Live At Massey Hall 1971 CD.

Halfway thorough his solo tour, Young decided to separate the two songs, and began to play them on guitar, cutting one single line: ‘Afraid/A man is afraid’ when the two songs became standalones. But to be completely accurate, while it was released on February 14, 1972, the album was much more than a valentine to Carrie Snodgress.

It’s an album that deals with love of all stripes, chronicling his budding romance with Snodgress, his affection for his ranch hand Louis Avila, his sad regret over Danny Whitten’s dependence on heroin, his own search for self-love.

More so, Harvest is the result of a confluence of serendipitous events, equally weighted by Young’s back injury – requiring him eschew his hefty electric guitars for much lighter acoustic versions; hence writing on that instrument – and falling in love with Snodgress.

The romance unleashed something in the ordinarily emotionally austere Young, allowing him to be more forthcoming, autobiographical and less oblique than he had been before on record.

He even chronicled the beginnings of his romance-cum-conquest of the actress in the third verse of the (much-maligned by feminists) song, A Man Needs A Maid. That is, of course, after first expounding in the first lines that all he really needed was ‘someone to keep my house clean, fix my meals and go away’, lines much more indicative of the character of the relationship than anyone would have suspected in those early days of 1971 when the couple met: ‘A while ago somewhere I don’t know when/I was watching a movie with a friend/I fell in love with the actress/She was playing a part that I could understand.’

It’s intoxicating for the listener to be able to crack open the door into the personal life of this brooding romantic. But if it was absorbing for fans to find him documenting the history of his relationship, it was even more so for Snodgress, who previously hadn’t had any notion who Neil Young was.

“I wasn’t a rock’n’roll girl,” she told the Los Angeles Times in 1990. “I said, ‘Neil Young, Neil Young. Where do I know that name from?’”

Nevertheless, she said, she fell “madly and immediately” in love with Young, and abandoned Hollywood to travel with the rocker and share his Northern California ranch. In 1972, she gave birth to their son.

As for her own career: “I decided that I was going to be in love, I was going to give it everything I had.”

Unfortunately, Young wouldn’t or couldn’t do the same. It was as if he had one eye fixed on the exit door – or as he so poetically put it in Alabama, speaking about the intersection of the then-new South and the old South and the problems it posed: ‘Your Cadillac has got a wheel in the ditch and a wheel on the track.’ He could have easily been speaking of himself in this relationship.

What’s unnerving is that after the ambiguity of A Man Needs A Maid, and his rather offhand declaration of love for Snodgress, he follows that song with Heart Of Gold, signifying, like Bono a decade after him, that he still hasn’t found what he’s looking for.

There are no accidents in album sequencing, and Young had to have thought hard about where he wanted to place Heart Of Gold in respect to the rest of the songs. Was the placement, the juxtaposition, a message to Snodgress, or to himself?

Young once described his music as being about “the frustrations of not being able to attain what you want”. When it appears that he had gotten what he wanted, if the love songs on Harvest are to be believed, he’s not completely comfortable with it.

Perhaps that “heart of gold” he’s searching for is his own, given the use of the personal pronoun: ‘I’ve been in my mind and it’s such a fine line that keeps me searching for a heart of gold.’ This particular journey may just be the search for self.

Whatever it was, this prospector’s search led Young to the top of the Billboard chart, giving him the only No.1 record in his long career, but also making him back away from his fame, all but disowning it.

He dismissed and denigrated the song in the liner notes for Decade. “This song put me in the middle of the road. Travelling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch. A rougher ride but I saw more interesting people there.”

Despite that claim, you can’t discount that Young met some interesting people during the first sessions for Harvest. He commandeered 70s folk-pop stars Linda Ronstadt and James Taylor to provide backup vocals for both Heart Of Gold and Old Man.

Young also convinced his cronies Crosby, Stills & Nash to appear on the record, prompting David Crosby to dryly comment, “Neil needs us about as much as a stag needs a coat rack”.

But Nash, Crosby and Stills’s vocal footprints give the Harvest tracks Are You Ready For The Country, Alabama and Words a richness and depth – and at times a lightness – that the songs wouldn’t otherwise possess.

The most revealing part of the entire album – other than the fact that Young wrote the lyrics for the 10 songs on the album in his own hand – is in the title track, where he sang, ‘Dream up, dream up, Let me fill you with the promise of a man,’ rather than the man himself.

While that signals an enormous amount of self-awareness about his limitations, it doesn’t absolve him of the responsibility of giving the relationship all he has, something made material when he sings: ‘Will I see you give more than I can take? Will I only harvest some?’

What did Carrie Snodgress think about when she heard that line? Was it a portent of a rocky future?

It wouldn’t be until 1979’s Rust Never Sleeps that Young even got close to complete emotional surrender, but the idea of Harvest would haunt him for years afterward. He named his 1992 album Harvest Moon, and gave his band during his 1984-85 tour the moniker the International Harvesters, silently asking the question of the one-time teenage egg farmer, what is it that he is harvesting, or wants to harvest.

As for the actual song itself: “Harvest is one of my best songs,” Young told his biographer Jimmy McDonough. “That’s the best thing on Harvest.”

He added, “I was in love when I first made Harvest. With Carrie. So that was it. I was an in-love and on-top-of-the-world-type guy. All those relationship songs – it’s I want to, but I can’t. Right good thing I got past that stage.”

“How did you do it?”

“Time, I guess,” Young said. “Getting the right woman. That was a good thing.”

Then there’s the issue of gathering the right band. Harvest marks the first time that Neil had recorded with the Stray Gators. This was a ragtag assemblage of Nashville outsiders that producer Elliot Mazer put together on a day’s notice after meeting Young at a dinner party he threw for the cast of The Johnny Cash Show at Quadrofonic studio, the facility he co-owned with David Briggs (not Young’s producer) and Norbert Palmer.

Among the 50 invited guests were Taylor and Ronstadt – she had also appeared on Cash’s highly rated ABC television show that night. Mazer knew Young’s manager Elliot Roberts from when they both lived in New York, so he invited him to drop by as well – which Mazer did, bringing his charge along.

Over the main course, Roberts introduced Neil to Mazer, and they began talking about studios and musicians. Young mentioned to the producer that he had some songs he wanted to cut while he was in town, and asked if he could get a drummer, a bass player and a steel player into his studio the next day.

Kenny Buttrey, who played drums on Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline and Blonde On Blonde albums, was available, but seemed to be the only one.

The A-team of Nashville musicians regularly went fishing on weekends, according to Mazer, so he had to dig deeper.

“Weldon Myrick, the steel player, couldn’t make it because he had to do his regular gig on The Grand Ole Opry. So we found Ben Keith, who went on to work with Neil for the next 30 years,” remembers Mazer.

The next morning, Mazer and Young met for breakfast at the Ramada Inn, and by that afternoon, Young was at the studio, moving things around so he could be next to the drums. He was going after a really minimal sound and wanted to control what Buttrey played, much to the seasoned drummer’s chagrin.

“Basically, every drum part I ever did with Neil are his drum parts, not mine,” he told Young’s biographer Jimmy McDonough. “‘Less is more’ is a phrase he used over and over.”

First they nabbed Troy Seals, a local songwriter, to play bass; Teddy Irwin, a session player, played guitar. A few hours later, by mere happenstance, Tim Drummond, who had also played with Dylan, showed up with his bass. Nashville photographer Marshall Falwell had spotted the bassist walking on the street and told him to go to the studio with his instrument to be part of the Young sessions. Drummond played with Young for the next two days, and is with him still.

The sessions were almost flawless. Heart Of Gold was cut in just two takes. The most daunting part seemed to be for Linda Ronstadt, who was out of her comfort zone with the pace at which Young worked. “The way Neil makes records, oh my gosh. I have a very, very meticulous way of working. I am an oil painter. I take a long time to get all the parts in tune… with Neil you don’t get the chance. You’re lucky if you’ve figured the part out, he does things so fast… it’s done and it’s brilliant. He’s really got an uncanny instinct to go for the throat.”

Bob Dylan may have claimed that when he heard Heart Of Gold on the radio in Phoenix, Arizona, he thought it was himself, but Young wasn’t looking to make his own Nashville Skyline. “The only time it bothered me that someone sounded like me was when I was living in Phoenix, Arizona, in about 72, and the big song at the time was Heart Of Gold," Dylan told Spin reporter Scott Cohen in 1985. “I used to hate it when it came on the radio. I always liked Neil Young, but it bothered me every time I listened to Heart Of Gold. I think it was up at No.1 for a long time, and I’d say, ‘Shit, that’s me. If it sounds like me, it should as well be me.’

"There I was, stuck in the desert someplace, having to cool out for a while. New York was a heavy place. Woodstock was worse, people living in trees outside my house, fans trying to batter down my door, cars following me up dark mountain roads. I needed to lay back for a while, forget about things, myself included, and I’d get so far away and turn on the radio and there I am, but it’s not me. It seemed to me somebody else had taken my thing and had run away with it, you know, and I never got over it.”

Apparently not, because 13 years after the release, Dylan was still vexing over it.

Decades after Harvest’s release, it’s somehow still polarising people. It’s been called the Neil Young album for people who don’t like Neil Young. Some critics discounted it for being too simplistic, too obvious. Others said it was too overblown and ponderous, using as evidence A Man Needs A Maid and There’s A World, both recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra.

Rolling Stone trashed the record upon its release, all but calling it a retread of After The Gold Rush with a steel guitar. In 2003, the magazine recanted, calling Harvest the 78th greatest album ever made.

Long-time Young stalwart Cameron Crowe called Harvest a “regression,” said the lyrics were “cliché”, and pounced on Taylor and Ronstadt for their “soggy background work”.

That dean of rock critics, Robert Christgau, damned it with faint praise, explaining that “the genteel Young has his charms, just like the sloppy one”. But there is a part of Young that doesn’t mind keeping people off-balance, a dedication to never doing the expected, even in small ways.

That included changing band members and configurations at will. And making a rather straightforward autobiographical record after four albums, one which showed him to be the inscrutable loner, often injured by love and loss, from the bewildered recriminations of What Did You Do To My Life to the wistful longing of I’ve Loved Her So Long, to asking for a woman to save his life in I’ve Been Waiting For You, on his first solo album.

Who can forget the mysterious females of Cowgirl In The Sand and Cinnamon Girl – the dream girls of Everyone Knows This Is Nowhere – and the lyrics and images, elusive and anticipatory. By the time Young released After The Goldrush, he appeared to have more of a deeper experience of love, loss and romantic redemption, but the best song from that disc, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was written about his CSN&Y bandmate Graham Nash’s breakup with Joni Mitchell.

That song showed – lyrically, at least – that even though he married Susan Acevedo in 1968 (and divorced in 1970), he had not allowed himself to totally lose himself in a relationship. Until Harvest time.

“Harvest was just easy,” he said after the fact. “I liked it because it happened fast. Kind of like an accidental thing. I wasn’t looking for the Nashville sound, they were the musicians that were there. They got my stuff down and we did it. Just come in, go out, that’s the way they do it in Nashville. There were no preconceptions. Elliot Mazer was in the right place at the right time.”

And so was Young, riding the crest of the introspective singer-songwriter wave that began in 1970 with James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James, and crested a year later with Carole King’s Tapestry.

Harvest has sometimes been called a game-changer, and has been charged with the advent of county rock, but that would be inaccurate. Bob Dylan hinted at that rock variant in 1967 with John Wesley Harding; its first birth pangs were felt with Gram Parsons’ International Submarine Band, and a live birth was executed when the Parsons-era Byrds released Sweetheart of the Rodeo in August 1968.

While Harvest carried the ball further down that country mile, it was much more a document of one man’s realisation of the hippie dream, complete with the ranch in the country, the actress in his bed, and a lament for pals whose lives were destroyed by demon drugs in The Needle And The Damage Done, which presaged Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten’s death.

That particular song wasn’t cut during Young’s two trips down to Nashville. Instead, it was recorded in concert on January 30, 1971, at UCLA’s Royce Hall, with background vocals by Crosby Stills & Nash, recorded by Mazer in New York.

Even though this is a document of Young’s relationships, there is still the taint of The Loner about Young that was true as much in 1972 as it is today. The unapproachable heart, the emotional stoicism, the early wounds from his parents’ divorce that never seemed to heal, and something that would fester on what is probably the second-best song on Harvest, Old Man.

Shortly after becoming the owner of Broken Arrow, a 1,500-acre ranch located in the hills south of San Francisco, Young penned a song titled Old Man, inspired by the caretaker of the ranch, Louis Avila. Young sang in the first line: ‘Old man, look at my life, I’m a lot like you are.’

Given Young’s age and his place in Toronto’s social stratum – his mother, Rassy, a TV presenter; his father, Scott, a celebrated sports journalist – the comparison seems forced. In fact, Young’s father assumed that the song was about him, something he addressed in his book about his son, Neil And Me.

“… [In] March of 1972 I took my family for a month in Florida, and was there just after Neil’s new album, Harvest, was released and went straight to the top of the charts within two weeks,” the elder Young wrote. “Every time I turned on my car radio in Florida I heard Heart Of Gold, the first single released from that album.

"Then, almost as often, I would hear another from that album, Old Man. Well, sure, Old Man pleased me a great deal. In Florida and back in Canada during the many months while Old Man was well up on the charts, people would mention it to me as if I were some sort of co-proprietor, at which I would just nod and smile like Mona Lisa. Never question a compliment is my motto. Old Man was also such a nice change from some of the songs whose accusatory gist I had applied to myself years earlier.”

A few months later, Neil was in Toronto, and father and son met up. After a walk, Neil said to the elder Young: “Something I should clarify. You know that song, Old Man?”

“Yeah, I love it.”

“It’s not about you. I know a lot of people think it is. But it’s about Louis, the man who lives on the ranch and looks after things for me, the cattle and the buffaloes and the food and all that. A wonderful guy.”

“’Oh,’ I said,” wrote the elder Young, sadly but sanguinely adding, “The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away.”

So what bound Neil Young with Louis Avila, his ageing caretaker, and not to his father? It could be the prospecting, the search for the gold of love. ‘I need someone to love me the whole day through,’ he sang. ‘Oh, one look in my eyes and you can tell that’s true.’

One of the first women to work in rock journalism, Jaan Uhelszki got her start alongside Lester Bangs, Ben Edmonds and Dave Marsh — considered the “dream team” of rock writing at Creem Magazine in the mid-1970s. Currently an Editor at Large at Relix, Uhelszki has published articles in NME, Mojo, Rolling Stone, USA Today, Classic Rock, Uncut and the San Francisco Chronicle. Her awards include Online Journalist of the Year and the National Feature Writer Award from the Music Journalist’s Association, and three Deems Taylor Awards. She is listed in Flavorwire’s 33 Women Music Critics You Need to Read and holds the dubious honour of being the only rock journalist who has ever performed in full costume and makeup with Kiss.