"I often see debates about album lengths on prog forums, and I’ve always been of the view that a record must be as long as it needs to be." How Cosmograf made Heroic Materials

With 2022's Heroic Materials Cosmograf's Robin Armstrong took inspiration from WWII veteran Geoffrey Wellum

The first album was a demo that sort of escaped, really.” Prog is reminiscing about the development of the Cosmograf project in the late 2000s with its sole creative force, the multi-talented Robin Armstrong. We’re discussing 2009’s End Of Ecclesia, though he also notes that there was an even earlier record that remains largely unheard called Freed From The Anguish, which, like his latest album Heroic Materials, has a World War Two theme.

Starting with 2011’s much-praised When Age Has Done Its Duty, Armstrong slimmed down from a ‘cast of thousands’ to become something of a one-man band. “Some of that was a bit cynical,” he admits, “I had seen other bands use this strategy of bringing in guests as a way of gaining press interest, so it seemed like a good way of getting credibility early on.

“But it went beyond that. I really started to enjoy giving them their parts and seeing what they came back with. Most often, it pushed the music in totally unexpected directions. I’m not averse to going back to that exciting approach, but over the last two or three albums, I’ve also enjoyed having that complete control and the speed of working that it gives. It really helped creatively to be able to get sketches down, and often those early ideas would end up on the album as the finished takes.”

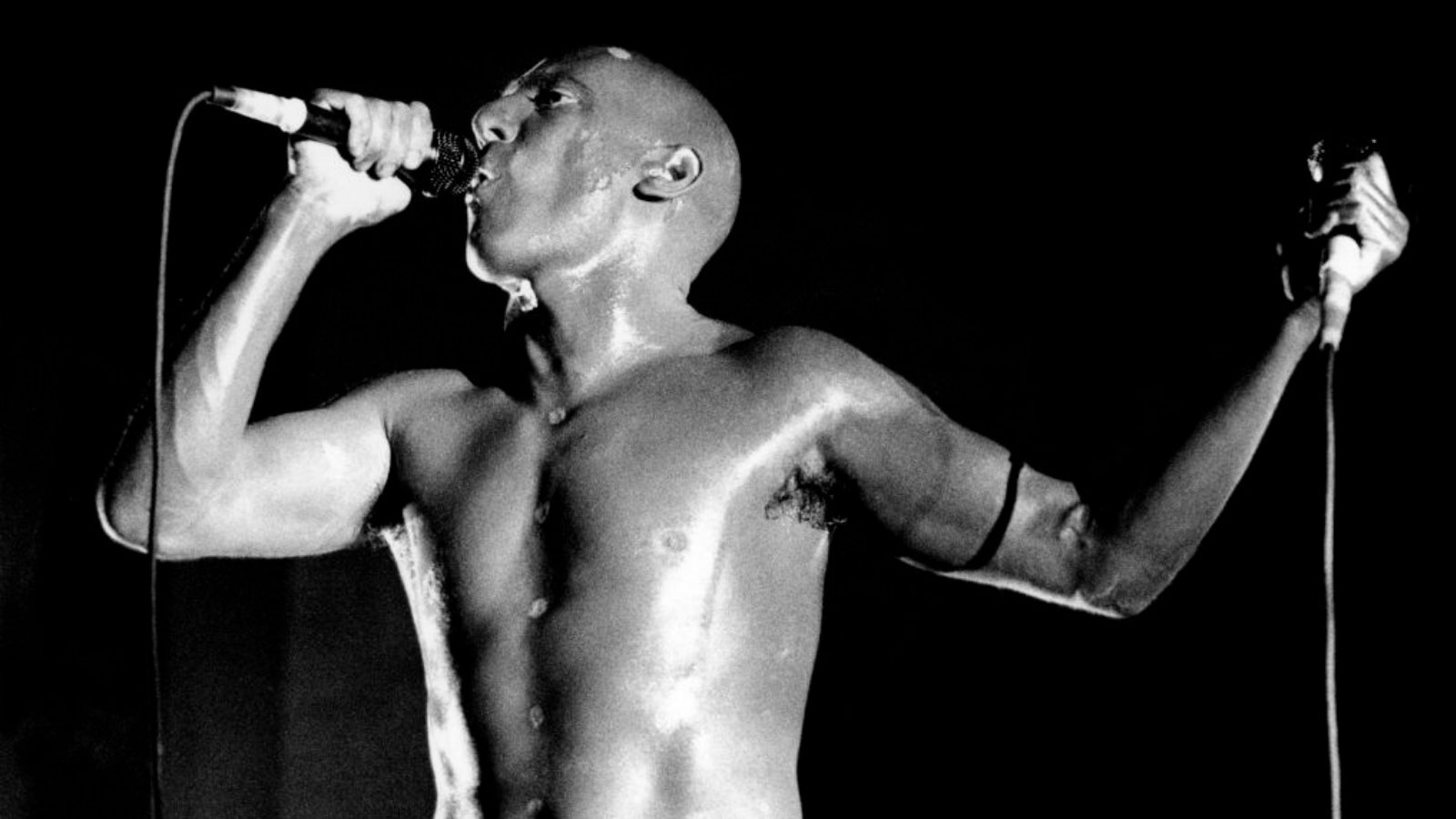

In particular, Armstrong has now become the main vocalist, both in the studio and when Cosmograf play live.

“I’ve developed a growing confidence in what I wanted to say vocally,” he says.

“I worked out that I didn’t need to get other singers on board unless there was a particular song that needed a certain style of voice. At first, I worried that I was copying vocalists, but I’ve finally found my way through it artistically and found my style.”

One of the benefits of the studio – particularly on Heroic Materials – is the ability to sing in different styles and to use vocal effects. Armstrong explains, “You might hear a Roger Waters-style delivery but then, in contrast, something with more effects in the way that Steven Wilson might do. But hopefully, I’m not being too derivative. I also liked the falsetto I was getting with my voice. I didn’t want to sing in character as if the album were a musical, but I wanted to get some of the fragility and tenderness of a 99-year-old man as he looks back on his life.”

Heroic Materials is certainly melancholic in tone, following on from the relatively up-tempo and rocky Rattrapante, released last year. Armstrong says that he doesn’t like to repeat himself too much, despite melancholia being a feature of Cosmograf music. “I wanted to do something more laid-back and symphonic from the outset. So, I wanted to keep to that downbeat tone,” he explains.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Another feature of the album is its brevity, at around 45 minutes. Again, there were practical considerations for this as well as artistic ones. “I wanted to put the album on a single vinyl LP,” he explains, “so for practical reasons, it needed to be relatively short. But in the end, it worked fine, and I didn’t have to make any creative compromises. I often see debates about album lengths on prog forums, and I’ve always been of the view that a record must be as long as it needs to be. However, there’s also a concentration span issue, and 45 minutes does seem to be the sweet spot for that, especially as many of the tracks on this album segue into each other, making it unfriendly for radio play and streaming. So, I’m promoting this as very much an album experience.”

Nonetheless, he has plucked out one track to act as a promotional tool: British Made, which both works in the context of the album but also as a standalone track in that it celebrates the beauty and innovation of British engineering.

“Well, Floyd – even within these massive art concept albums they put together –

always had one nugget you could pluck out,” he explains. “So, it gave me the idea to use British Made as a little lead into the album.”

Speaking of Pink Floyd, does he ever worry that people will think the album is too influenced by them? “It’s a style I really enjoy and it’s a great frame of reference. I’m not ashamed [of the similarities] at all, but some Cosmograf albums don’t sound like them at all. Porcupine Tree are another big influence. A friend gave me Fear Of A Blank Planet and it blew my mind. That album was my way into that sound.”

Despite the seemingly straightforward idea behind British Made, the album’s theme is anything but simple and it reveals more layers on closer examination. “Each Cosmograf album has the presentation of its title and of what the concept appears to be, but there’s always some duplicitous meaning, ambiguity or allegory there,” he explains. “There’s always more than meets the eye, so you look at the Spitfire on the cover and you think that this is a story about a World War Two veteran. But I saw it as a perfect metaphor for someone who couldn’t really change. His life was defined by something that happened when he was 18 years old, and he spends the rest of his life coming to terms with that but also the world is changing around him while he’s stuck in time. He also realises the human race is in danger of making life untenable on this planet. So, there’s this climate change concept going on in parallel, and I thought that it was interesting to mix the two ideas together. Billy feels that he can’t change but also knows that unless he does, there’s no future for mankind. Of course, we are all dealing with these ideas; we have a nostalgia for the past, but we also recognise that we must move on if mankind is to progress.”

While the album’s main character – William ‘Billy’ May – is fictional, the inspiration comes from a factual source. “He’s a composite, but largely based on Geoffrey Wellum, the famous Battle Of Britain veteran,” Armstrong explains. “I pulled out a little of his story= to understand what a typical Spitfire pilot would have been asked to do. But the pictures of a pilot you see in the album booklet are actually my son.”

It’s clear that the character of Billy has also been used to channel some of Armstrong’s own views, particularly on the subjects of ecology and sustainability. “We’re in danger of repeating the same mistakes,” he says. “Although we are moving towards greener lifestyles, we’re doing it in the wrong way. We are throwing increasing [amounts of] materials at EVs, but we’re not really solving the problem. The album uses the example of the E-type Jaguar, lauded for its form and its beauty, but rather than cherish what we have, we’re building electric cars with batteries that don’t last long, so soon we’ll quickly throw those out and replace them with newer models. It seems we still haven’t beaten the idea of consumer need. If we put more effort into maintaining and sustaining what we have – thus Heroic Materials – we wouldn’t be going down this path. That’s what the song The Same Stupid Mistake is about, but I’ve also protected my own worries on this subject onto the character of Billy.”

The album does end on a moment of promise, however, via the brief final track,

A Better World. “At least there’s a nugget of hope that we won’t make the same mistake as Billy; we’ll learn from our errors by looking inward and changing to build a better planet,” Armstrong states. Let’s hope he’s right.

This article originally appeared in issue 134 of Prog Magazine.

Stephen Lambe is a publisher, author and festival promoter. A former chairman of The Classic Rock

Society, Stephen has written ten books, including five about music. These include the best-selling

Citizens Of Hope And Glory: The Story Of Progressive Rock and two books about Yes: Yes On

Track and Yes In The 1980s. After a lifelong career in publishing, he founded Sonicbond in

2018, which specialises in books about rock music. With Huw Lloyd-Jones, he runs the Summer’s End

and Winter’s End progressive rock festivals, and he also dabbles in band promotion and tour

management. He lives in Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire.