How Monkey Wrench brought Foo Fighters a whole new audience

The story behind Foo Fighters' 1997 classic single

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

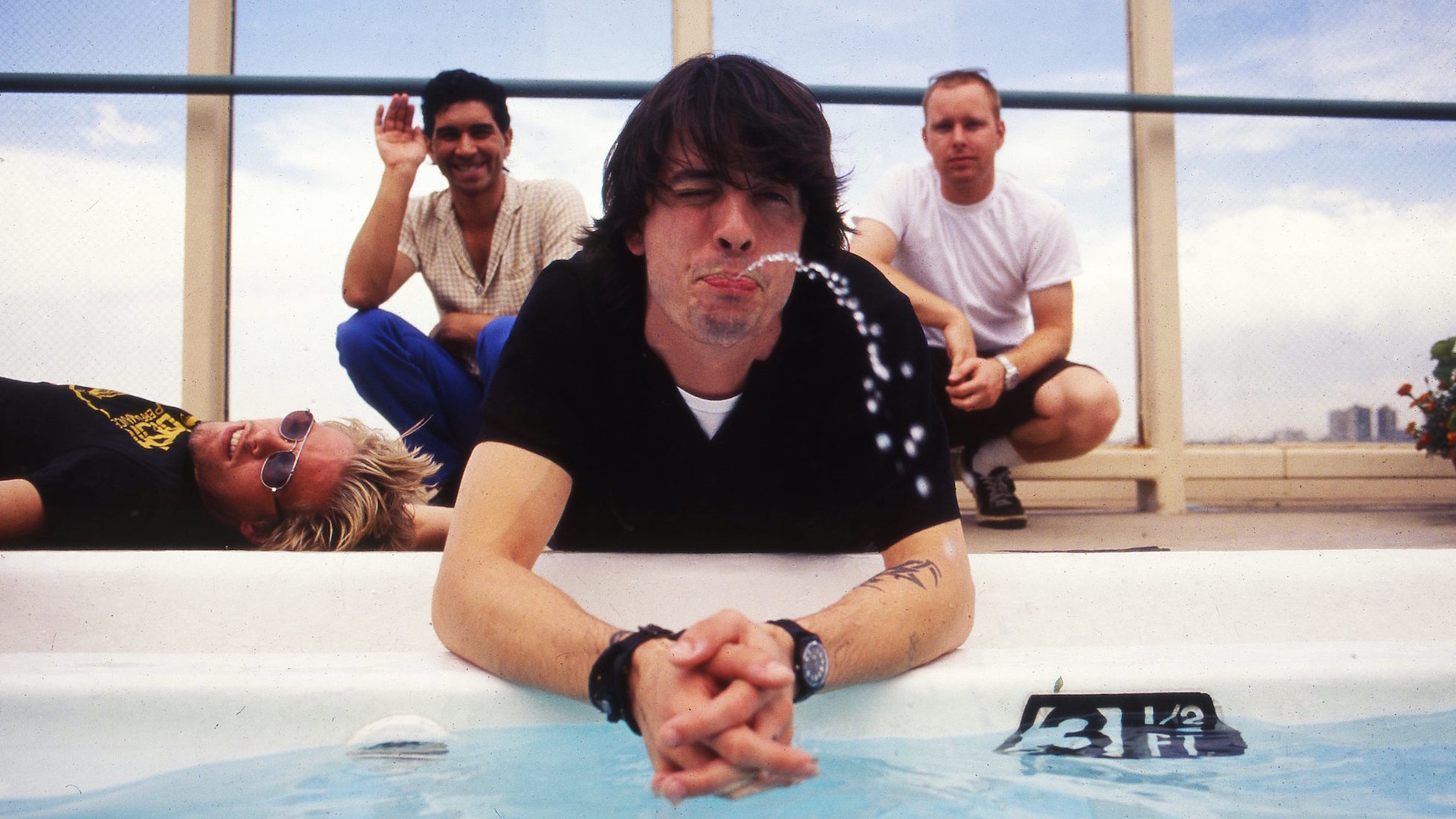

It’s hard to believe it now, but there was a time when the Foo Fighters were just seen as a superstar’s indulgence, a quirky side-project that would disappear as soon as an empty drumstool appeared in the next available supergroup.

Then Monkey Wrench came out.

Like a turbo-charged version of The Cars’ new wave rock caught in a head-on collision with some lagered-up grunge band, Monkey Wrench was faster, tighter, ballsier and, importantly, more joyous than anything Grohl’s previous band – the newly sainted Nirvana – had managed. And after all those years of complaint rock, it was a welcome relief.

In 1997, as Britpop crumbled, Radiohead went even more miserable with OK Computer and drum ’n’ bass 12”s were top of every teenager’s shopping list, it was hard to work out exactly what Monkey Wrench was. It wasn’t punk. It wasn’t grunge. It wasn’t metal. It wasn’t pop.

In fact, it was all those things and more. It was three minutes and 51 seconds of driving guitars, pop melodies, and a soft-then-loud dynamic that culminates in a bridge full of shouty metal-inflected vocals. Sound familiar?

The lead single off 1997’s The Colour And the Shape album, the song was born out of difficulty. Grohl knew that this album had to answer their critics. “I knew it had to be good,” he says. “I knew it had to solidify the band as a legitimate band. It couldn’t be just another six days in the studio. It couldn’t be a basement demo.”

Grohl’s songs became more ambitious. They got in producer Gil Norton – a guy who had produced indie’s superleague: Sugarcubes, Pixies, Echo And The Bunnymen – and a renowned perfectionist. “Gil is awesome in that he fucking wrings you out,” says Grohl. “He wants every last drop of performance and song. It was intense.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Dave Grohl’s private life was pretty intense too. “I was going through a divorce. I was falling in love with someone else. I was living out of my duffel bag on this cat-piss-stained mattress in my friend’s back room with 12 people in the house. It was fucking awful.”

With the recording almost finished, the band realised that their grand vision wasn’t really coming across. Drummer William Goldsmith was unhappy and ‘wasn’t really gelling’ so Grohl started re-recording some of the songs himself, adding his own drum tracks. Impressed, producer Norton urged him to come into the studio to record those versions. Left on the subs bench, drummer Goldsmith left the band. Now a three-piece, Grohl – recently voted rock’s greatest living drummer by Classic Rock magazine (second only to his hero, the late John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, in a poll to find rock’s greatest drummers) – played the drums as the band re-recorded almost the entire album.

Seen in this context, Monkey Wrench’s lyrics about not wanting to be a spanner in the works, could be seen to be as much about Goldsmith’s departure as Grohl’s divorce, with Dave singing from Goldsmith’s/the spurned lover’s perspective. A bitter kiss-off to someone, lines like “I’d rather leave than suffer this” and “one last thing before I quit” sound more like the ending of a working relationship than a romantic one.

If the lyrics are downbeat, the music is anything but. Kicking off with a slamming, punk-pop guitar riff, there’s a spectacular moshpit-confusing stop-start before the verse begins. Performed live or heard down your local rock club, the pause completely wrong-foots you: all you can do is jump, headbang or attempt some air-drumming. Either way, from that moment on it’s got you. From then on it just builds and builds, propelled by some spectacular drum fills, the emo-like shouty bit in the bridge, and the anthemic “fall in, fall out” backing vocals.

Even old-fella-of-rock, Queen’s Brian May, thinks it’s a classic. In 2002, Brian compiled an album called The Best Air Guitar Album In The World… Ever and included Monkey Wrench alongside classics like Smoke On The Water, The Boys Are Back In Town and Paranoid. “The number one criterion was, if you hear the song you have to jump up and do something,” explained the curly one. “Preferably in the first 10 seconds. To me, the Foo Fighters are totally at the cutting edge of what rock music’s about today. Monkey Wrench wasn’t as big a hit as it ought to have been, but I think it had a big effect on all bands in general.

“[With Taylor] you’ve got two of the greatest drummers in the world in that band,” says May. “And one of them plays incredible guitar, sings incredibly well and writes incredible songs. So, Dave Grohl, thank you very much and I hate you.”

The making of The Colour And The Shape

The 10 best Foo Fighters songs tucked away on b-sides

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.