"F**k you, follow that!": The electrifying story of AC/DC's masterpiece, Powerage

In 1978, AC/DC had their backs against the wall. Dismissed by critics, misunderstood by their record label and fighting for their very survival, the Young brothers and Bon Scott dug deep: the result was Powerage, one of the finest hard rock albums ever

It was close to midnight when AC/DC arrived at CBGB. No-one working at the East Village venue was aware of any invitation being extended to the band to perform at the club, but as local power-pop quartet Marbles exited the stage and the Australian group pushed through the crowd carrying their guitars and amplifiers, no-one dared speak up to challenge the bullish interlopers.

Malcolm Young’s group were still buzzing from a gig earlier in the evening, opening up a three band bill, headlined by The Dictators, at the Palladium on East 14th Street: Angus Young hadn’t even bothered changing out of his blue velvet school uniform for the short trip downtown. The prospect of playing New York’s infamous punk rock dive bar appealed to ‘DC’s sense of mischief and their love of in-yer-face confrontation. Though the hard-bitten Aussies were dismissive of English punk rock’s posturing and politics – “In every interview we did when we came to London we’d be saying, We’re not fucking punks, we’re a rock ’n’ roll band,” Malcolm Young told this writer in 2003 – they had a grudging respect for the US scene.

“The punk thing is pretty cool in America,” Angus Young conceded. “It’s just a young thing, a new breed type thing.”

Ahmet Ertegun, the President and co-founder of Atlantic Records, arrived at CBGBs on the evening of August 24, 1977 to find Bon Scott standing outside 315 Bowery pissing into a jar. Given the legendarily horrendous state of CBGB’s toilets, the record mogul may well have applauded the singer’s resourcefulness. He was certainly impressed by the lack of nerves the band displayed when they stepped onto the club’s stage.

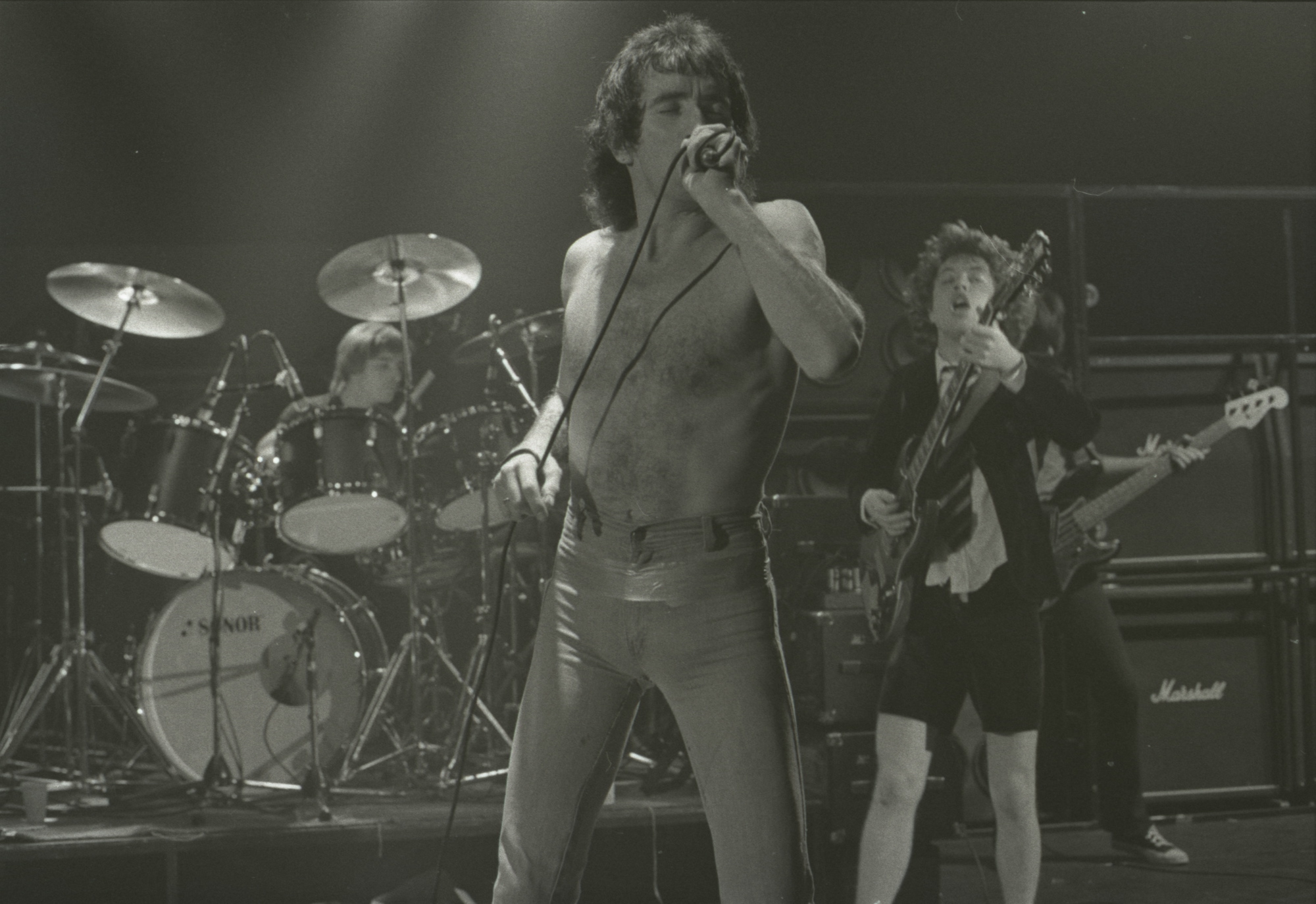

In terms of song selection, ’DC’s second set of the night, ushered in by Cliff Williams’ throbbing Live Wire bass line, was identical to their first, but CBGB’s anarchic ‘anything goes’ vibe suited the Aussie quintet’s raw energy better. During The Jack, Scott hoisted Angus Young onto his shoulders for a walkabout, both men bare-chested, dripping sweat on bemused patrons as they parted the audience. For his closing solo on ’DC’s muscular take on blues standard Baby, Please Don’t Go, Young exited the building through the front doors, exchanging pleasantries with the Bowery’s homeless community outside the club as he peeled off R&B licks in the muggy Manhattan air. This didn’t tend to happen at Talking Heads or Television shows.

Two days later, AC/DC’s name appeared in the New York Times for the first time, with music writer John Rockwell offering his critique of the band’s Palladium performance. Rockwell detected traces of “flashy, showbiz pretentions” in the quintet’s set, but seemed quite taken by the group’s “deliberately demented” guitarist.

“Mr. Young wears British/Australian schoolboy attire when he first appears—short pants, a matching jacket, tie, beanie and bookbag,” he wrote. “But soon he is tearing most of his clothes off, careening about the stage, drooling, leering and slobbering. What makes all this mildly interesting is that he is a good, sharp, moderately clever rock guitarist in the midst of all the acrobatics.”

“Ultimately it’s to little real avail,” Rockwell concluded, somewhat sadly, damning Bon Scott as “undistinguished” and the band’s material “puerile-provocative”. “AC/DC is pure entertainment with next to no pretentions to touch people's emotions.”

John Rockwell was not the first writer to underestimate and patronise AC/DC, and he would not be the last. But within nine months the Australian band would return with an album that would ram his words down his throat.

AC/DC were often at their best when their backs were against the wall, when they had something to prove, adversaries real or imagined to fight. Malcolm Young liked to tell a story, about a night in 1976 when his band supported The Stranglers somewhere in the north of England, which perfectly illustrated ’DC’s combative, recalcitrant attitude.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“When [The Stranglers] walked into our shared dressing room they took one look at us with the hair and went, ‘Fucking hippies’,” he recalled. “Bon was like, ‘What’s that you cunt?’ I was getting between them going, Fuck them Bon, we’ll do our talking onstage.”

As Young recalls, a wound-up AC/DC steamed through a ferocious 25 minutes on-stage and “blew the place apart”.

“We went back in and said, Fuck you, follow that. They were sitting there with their mouths open, they couldn’t say a fucking word. We’d always stand up to anyone. We used to fight a lot.”

In the run-up to the making of Powerage, particularly where the US was concerned, AC/DC had no shortage of battles to wage.

Rolling Stone’s December 1976 review of High Voltage, the group’s first international release, slammed the album as an “all-time low” for hard rock: “Stupidity bothers me,” wrote reviewer Billy Altman. “Calculated stupidity offends me.” The negative press feedback led to the cancellation of two proposed showcase gigs for the band in Los Angeles. Worse was to follow when Atlantic refused to even release the band’s next album, the bruising, irreverent Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, in America: the US office’s A&R team actually lobbied Ahmet Ertegun to drop the band from the label’s roster.

“Nobody in America liked them,” admitted Phil Carson, the UK-based talent scout who signed the band to a 15 album deal. It was only Carson’s powers of persuasion, and, crucially, his willingness to pare back DC’s budgets by $10,000 per album, which kept them on the label.

Raw and explosive, *Let There Be Rock, released in the US on July 25, 1977, vindicated Carson’s unwavering support and received a warmer reception at US radio , but peaked at a lowly number 143 on the Billboard 200. By then, the quintet – with Englishman Cliff Williams drafted in to replace bassist Mark Evans - were already in Sydney at George Young and Harry Vanda’s studio, demoing tracks for an album they felt sure America could not ignore. First though, they had to prove to their sceptical US label that there was an audience out there hungry for something other than saccharine AOR or flavour-of-the-month punk rock.

AC/DC’s Stateside assault began on July 27, 1977 with a show supporting Canadian rockers Moxy at the Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin, Texas. On the eve of the show, the ever-curious Bon Scott went AWOL, having befriended a group of Mexican workers in a local hostelry: as the minutes ticked down to showtime, there was still no sign of the singer, and a mounting sense of alarm coursed through the camp.

“Ten minutes before they’re due to go on, with the doors to the place long open and all the people there, I’m standing outside hoping and praying Bon’s going to show up,” tour manager Ian Jeffrey recalled to AC/DC biographer Mick Wall. “Next thing this truck comes hurtling over the horizon with AC/DC music blaring out of it. It‘s Bon with ten of his new best friends, all holding bottles of whisky and joints in their hands. It pulls up, Bon jumps out and says to me, ‘Ian, this is Pedro and this is Poncho, etc, can you get them all on the guest list?’ Meanwhile, the brothers are going nuclear.” The show would prove a cathartic release.

“AC/DC stole the show,” San Antonio-based photographer Al Rendon told the Austin Chronicle in 2008. “Angus Young drove into the crowd and was carried for as far as his guitar cord would allow him to go. He was literally walking on people's hands.”

“The vibe was there,” Moxy guitarist Earl Johnson admitted. “Everyone knew they would break.”

In the weeks that followed, ‘DC jumped aboard every show they could find, supporting REO Speedwagon, Foreigner, Mink DeVille, the Michael Stanley Band, Santana, Johnny Winter. With each show, their confidence and their faith that America was theirs for the taking grew.

Following their CBGB show, Bon and Angus met the American media for the first time. They were in a feisty mood when interviewed by John Holstrom for issue #14 of New York fanzine Punk, with Angus listing “fucking” and “hunting sharks” as his hobbies. Asked what kind of girls they liked, Angus responded “Dirty cows” while Bon was more explicit: “A nice clean dirty one,” he replied. “Clean c**t, dirty mind.”

Following this, Holstrom asked the lairy singer for his definition of the meaning of life. “As good a time, and as short as possible,” Scott replied.

One week on, AC/DC made their debut West Coast bow with three nights at the legendary Whisky A Go Go club in Los Angeles: Iggy Pop, Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler and Kiss man Gene Simmons were among those who showed up. In attendance too, was Sounds writer Sylvie Simmons.

“Onstage, cardboard cuts-outs of a Heavy Metal-cum-Punk band; coupled with music, heavy, bludgeoning Rock at its most manic,” she observed. “Meanwhile, back in the dressing room taking it easy, the band sit with their feet up, having a drink. None of this audience-performer participation lark. No headaches or ulcers. A new generation of calm, unneurotic rock stars. While record companies are dashing around snapping up anything that even smells of Punk, these beer-swilling, bad-mouthing, well, Punks, seem to have been ignored in the rush. Unfazed, they have been supporting bands and headlining in clubs up and down the country. Apart from a few language problems, they’re having fun and winning fans.”

“We may be little,” said Angus Young, “but we make a lot of noise.”

The band returned for a second tilt at the US in November. This run saw the quintet supporting Rush, UFO, Aerosmith, Kiss, Blue Oyster Cult, Styx and play a clutch of co-headline dates with Cheap Trick. On December 7, the band returned to New York for a special intimate show at Atlantic Studios.

Their eight song set – Live Wire, Problem Child, High Voltage, Hell Ain’t A Bad Place To Be, Dog Eat Dog, The Jack, Whole Lotta Rosie and Rocker – was broadcast live on Radio WIOQ in Philadelphia, and a recording of the show, tweaked by George Young, was later distributed to radio stations nationwide. Before they returned to Australia, the group were given a glimpse of what US success could mean, with a gig in front of 19,000 Kiss fans in Landover, Maryland. Their appetites – for success, for women, for a true emotional connection with fans – were well and truly whetted.

“It can get to be a drag being in a different hotel room every night and not knowing where you put your toothbrush or a clean pair of drawers,” Bob Scott reflected to Sylvie Simmons. “But what’s the alternative? It’s even more boring being stuck in front of a conveyor belt at some factory every day of your life for the next 60 years, like a lot of the kids who come to see us… which is where we’d all be now if it wasn’t for this life. I’d be stupid to knock it, it’s great.”

“And how can you get bored with so many different beautiful women around?”

Work on AC/DC’s fourth internationally-released studio album began in earnest at Sydney’s Albert Studios in January 1978. The sessions, with long-time collaborators Harty Vanda and George Young were intense: the band would rehearse songs from 8pm to midnight, and track them from midnight to 8am. The intent was to make an album that could stand toe-to-toe with anything recorded by the superstar acts ‘DC were now accustomed to sharing stages with.

“We were happy to stay in the same area as Let There Be Rock because all that stuff was going down so well on stage,” Malcolm Young reflected. “The record company were starting to push us for hit singles, and we were just digging in our heels and going for it.”

That Powerage is the only AC/DC album title not to feature in a chorus speaks to one of its key virtues – subtlety. Admittedly there’s nothing subtle about full-tilt yob-rock throttlers Riff Raff or Kicked In The Teeth or the exuberant Up To My Neck In You, but elsewhere, on the reflective Down Payment Blues, the murderous revenge fantasy What’s Next To The Moon and the sobering Gone Shootin’ – Bon Scott’s pained, poignant love letter to a heroin-addicted girlfriend – ‘DC exhibit a sense of discipline, maturity and reined-in power that comes with inner confidence and belief in the source material. Rock’n’Roll Damnation was a compromise, a nakedly transparent attempt to hand Atlantic a hit single, but elsewhere, there were quirks and tics which spoke of a band sure in their art. AC/DC had come of age.

Powerage is also unquestionably Bon Scott’s finest hour. Much of the album’s emotional sting is rooted in the singer’s perceptive sketches of disappointed, desperate men pushed beyond breaking point by lost love and empty pockets. Scott always had empathy for the marginalised, the broken and bruised, the dreamers and schemers, and, now a world traveller in his thirties, he had perspectives that stretched far beyond outback bars and motel bedrooms. Down Payment Blues married aspiration with harsh reality (“Living on a shoestring, a fifty cent millionaire”), Gimme A Bullet ditched Jack The Lad swagger for introspective self-analysis (“She hit me low, said ‘You go your way, I’ll go mine’… ain’t no cure for the pain in the heart”), Gone Shootin’ detailed a dysfunctional relationship with gut-wrenching honesty (“I took an offer in another town, she took another pill…”).

Crucially, though, throughout Powerage, there is always a sense of hope, always a glimpse of blue skies for those knocked down in the gutter, not least within gambling parable Sin City at the album’s core, a defiant ‘Do your worst, cunts!’ roar in the face of stacked odds and an inevitable beatdown.

The album is Bon at his most emotional, a masterclass of street poetry : perhaps John Rockwell’s New York Times review had stung. Looking back on Bon’s lyrical contributions 12 years after his death, Malcolm Young commented, “What hurt me more than anything was that Bon never got the recognition due to him when he was alive.”

The first AC/DC album to be released almost simultaneously in Australia and internationally, and the first of the band’s records to use a single cover image – an electrified Angus – in every market, Powerage did not immediately change AC/DC’s fortunes.

Released on May 5, 1978 in the UK, the album peaked at Number 26, some nine places lower on the chart than its predecessor Let There Be Rock, but with Rock’n’Roll Damnation it did secure for the band a first Top 30 single, and, on June 8, 1978, introduced by Noel Edmonds, a coveted first appearance on Top Of The Pops.

In Australia the album didn’t crack the Top 20 (peaking at Number 22) while in America it peaked at Number 133. But the band were emphatically creating a buzz on the live circuit. On July 23, 1978 the band opened up for Aerosmith, Foreigner, guitarist Pat Travers and America’s hottest new rock band, Van Halen, at the Day On The Green festival at the Oakland Coliseum, and absolutely killed it.

“I was standing on the side of the stage thinking, ‘We have to follow these motherfuckers?’” Eddie Van Halen later admitted.

“We got there early because we wanted to see all those bands, because it was an amazing bill,” Aerosmith’s Joe Perry told me in 2016. “I was introduced to AC/DC when we were lucky enough to have them open for us at shows on the Draw The Line tour in 1977: I was absolutely blown away the first time I saw them, and I’ve been a really big fan ever since.

"When you saw them live they had everybody on their feet, including me. They didn’t need any production, they didn’t need any lights, they just needed their guitars, their amps and plenty of watts, and they’d destroy the place. They were pretty mellow guys off-stage, but once they stepped onstage, they were on fire. They’re rock’n’roll at its best, the real deal.”

By the end of the band’s US tour, Powerage had sold 200,000 copies, more than the combined sales of High Voltage and Let There Be Rock. If this wasn’t the breakthrough album Atlantic were hoping for, it at least proved AC/DC had momentum, were going in the right direction. Crucially, though the band hated it, the inclusion of Rock’n’Roll Damnation on the album was an indication that this most stubborn of bands could be nudged towards making compromises, at least when said compromises were emphatically in their own interest. Next time out, Atlantic would take the band out of their comfort zone, pulling them away from big brother George, and pairing them with producer Mutt Lange for what would turn out to be their first million-selling album, Highway To Hell.

“We’d had our own way for a few albums so we figured, let’s give them what they want and keep everyone happy,” Malcom Young admitted with typical blunt honesty. Post-Powerage, AC/DC would get louder, slicker and bigger, but they would never again display this much heart, soul and humanity.

“People will know Highway To Hell and Back In Black because they’re the albums with the big radio songs, but people who’re really into AC/DC understand that Powerage is a classic album, a milestone,” says Joe Perry. “These might not be the AC/DC songs that you hear on the radio or necessarily hear on jukeboxes in bars, but no-one writes rock’n’roll better than this.”

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.