"Purple is like an old love affair and love can be very close to hate": Deep Purple on chemistry, magic, and the birth of Perfect Strangers

We travel back in time to 1984 and talk to the reformed Deep Purple as the ready themselves to release comeback album Perfect Strangers

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

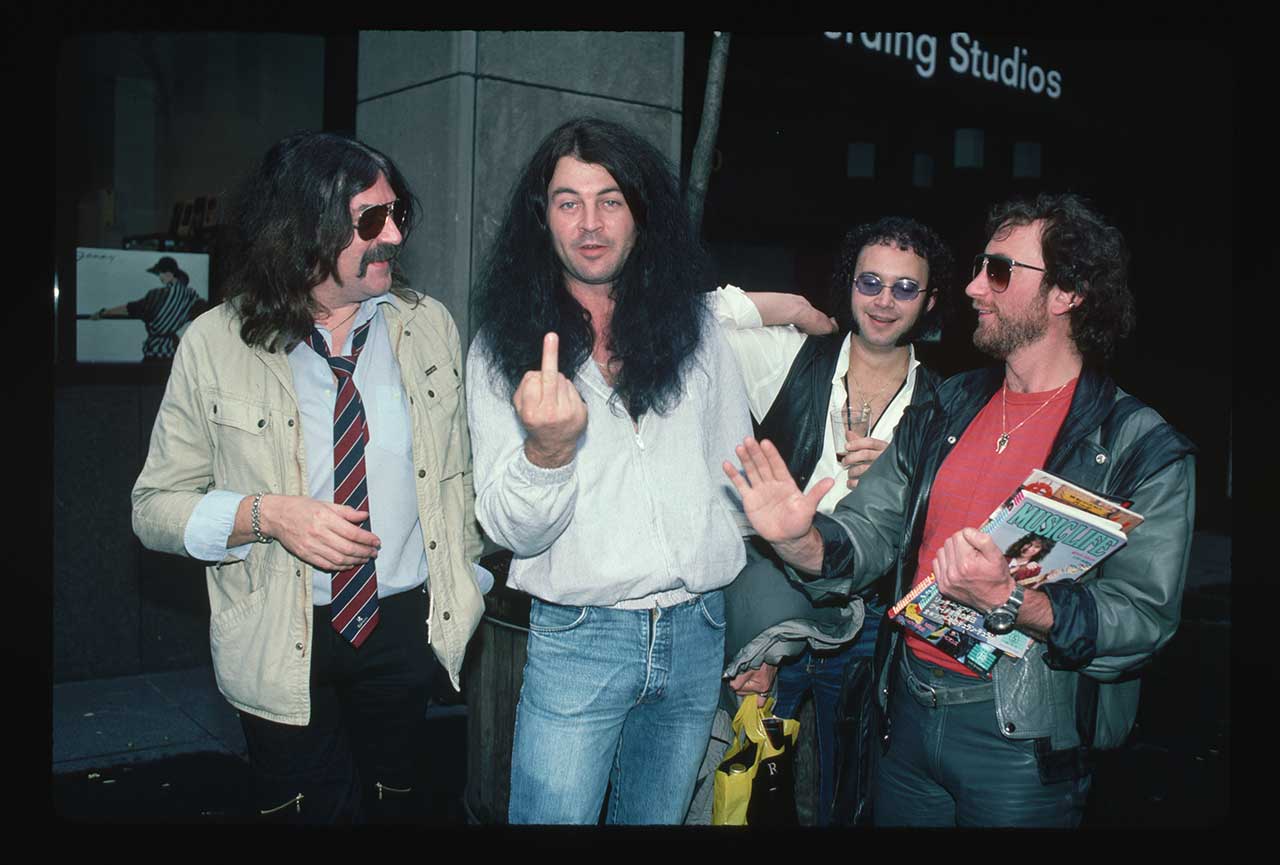

October 1984: after years of false starts, rumours and innuendo, the classic Mk II version of Deep Purple got back together. While undoubtedly a mega event in the history of rock, the re-formation didn’t catch the imagination of the record-buying public in quite the manner you might have expected.

In place of a lot of shouting from the rooftops and dancing in the streets, you detected – from punters as well as press people – a feeling of caution, of guardedness, and an attitude of: ‘Okay, big deal, so you’ve reunited – now get on with it and show us what you can do.’

Well, Gillan, Blackmore, Glover, Lord and Paice did just that, releasing their comeback album, Perfect Strangers. It was a safe, solid effort, neither mind-blowingly magnificent, nor trite, tedious or interminable.

What we expected I don’t know, but the record did improve with repeated listens. Purple make it sound so easy: with a minimum of fuss and bother, they fell right back into the Machine Head groove. Perfect Strangers was sophisticated rock played with virtuoso ability.

Years later, it can be seen as Purple back at, if not their very best, then certainly very close to it. Like most people I had some misgivings and reservations about the Mk II Purple reunion, let alone their right to exist at all in the synth-swamped, pop overkill world of the 1980s. But after talking to each of the reunited Purple members I couldn’t help but be mightily impressed by their high level of enthusiasm and commitment.

That upbeat mood wouldn’t last – but that’s Deep Purple for you. Should we really have expected anything different? The five of them were back together and, the overriding feeling was like a family meeting up once again, after spending a decade apart. First time around, the Mk II line-up imploded after 1973’s Who Do You Think We Are album, and vocalist Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover left, to be replaced by David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes.

Money may well be the big reason why the re-formation came about – Gillan, for one, had certainly got his fingers burned when he briefly joined Black Sabbath for 1983’s Born Again album. So, to a lesser extent, did Ritchie Blackmore with his latter-day incarnations of Rainbow. But there were several other reasons behind the Mk II reunion as well.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

There was the burning desire to inject a bit of class into rock’n’roll. There was the will to prove that the quintet could still cut it as musicians after all those years in the wilderness. There was a great feeling of meeting up with long-lost friends after a long time spent apart, and above all, there was the sheer joy of playing together once again.

Back in autumn 1984 I met up with the Purps in an odd little rehearsal room situated in the town of Bedford, of all places. Apparently, the band wanted to start putting their live show together in an out-of-the-way location, away from a big city tinderbox atmosphere.

The room itself was a kind of olde worlde wedding reception-style annexe to a wine bar, with plenty of mock Tudor beams, horse brasses and paintings depicting hunting scenes on display. Thick blankets shrouded the windows to soak up the sound and also keep that pesky daylight at bay. On the door leading to the rehearsal area was attached a plaque, on which was inscribed, in medieval script: ‘The Antico Room’.

The cynics among you might say that, bearing in mind Purple’s less than spring chicken status, the fact that they were occupying a room with that particular name is more than somewhat apt. Anyhow, I spoke to all five members of the band, and the edited highlights is what follows.

Doubtless, in the Depeche Mode-dominated 80s, many people will find your [Jon Lord’s] style of keyboard playing old-fashioned. What do you have to say to them on this?

Jon Lord: They may well do, they may well do. But I would like to say this to my detractors – indeed to Purple’s detractors: why shouldn’t a hard rock band still at the height of its powers be able to exist alongside the likes of, as you say, Depeche Mode?

Music is an international language, a receptacle for people’s emotions and feelings. It’s one of the most wide-ranging of all the arts and there’s room enough in there for all of us.

How do you think the average 80s rock fan views the Deep Purple reunion? With enthusiasm? Cynicism? Or a complete lack of interest?

Ian Paice: The last couple of years I’ve done a few drum clinics for the people who’re nice to me and give me something to play with. Obviously you meet the kids and they ask you things. And, like, one out of three questions would be: ‘Why don’t Deep Purple get back together again?’

It was always very hard for me to give a straight answer. I’d say, ‘Well, it’s very difficult, you see, some of the guys are doing this, some of the guys are doing that, we’ve got commitments.’ When it takes three minutes to give an answer, you start to realise that you’re making excuses, and not giving reasons. But it made me realise how many people still look at what we did as a kind of blueprint for what goes on now. So, when we finally did manage to get back together in March or April of this year [1984], it was like – thank God for that! We’re all talking sense at last!

There are so many people out there who want to see what it is all about. I’m not saying they’re necessarily converts, but they’re curious as hell. Mind you, we’ve got a lot to prove. If someone comes along to see us, and at the end of the evening they go: ‘Okay, it was alright. So what?’, then we’ll have failed. Totally. But if we’re as successful as I think we’re going to be and that same person goes: ‘Yeah, it’s true... ’, then we will have vindicated everything.

This is what it’s about; there’s an amazing magic and chemistry that makes Deep Purple work better in this sphere of music than anyone else. Don’t ask us why, it just does.

What did you [Ian Gillan] think of the album, Born Again, that you recorded with Black Sabbath a year ago?

Ian Gillan: It was brilliant. Absolutely fucking sensational... until it was mixed, and totally destroyed. I went away for holiday after we’d finished recording it, I was well pleased. I thought, ‘I’ll leave the guys to it now, they’ve been around for years; they know what they’re doing’. But as soon as I went away – as I understand it, anyway – all these outside influences started creeping in.

When I came back off holiday I found they’d sent me a bundle of 20 Born Again albums. I looked at the cover and puked. I put the LP on the turntable and was disgusted by it. It was just garbage. In a rage, I then went and smashed all of the 20 albums to pieces.

So now you’re back with Deep Purple, you must be raring to go?

Ian Gillan: Absolutely. Perfect Strangers is the best album we’ve ever done, if I play it once I have to play it 40 times. Really, I’m that proud of it. That’s quite a statement.

So what was your favourite Deep Purple album prior to Perfect Strangers, then?

Ian Gillan: Fireball. That was one of the most important albums Deep Purple ever did. After In Rock, it was imperative that we did something progressive. Apart from tiredness and overwork, one of the reasons I left the Mk II Purple was because we were beginning to write songs in the vein of public expectation; we weren’t being innovative enough.

That was a great anathema to me. Whereas, on Fireball, we were really pushing ourselves to the limits with songs like Fools, No One Came, Anyone’s Daughter and The Mule. Fireball is seen as an interlude by most people, but I think it laid a cornerstone for Machine Head, I really do. There would never have been a Machine Head if there hadn’t been a Fireball. I never thought I’d be more proud of an album than Fireball – but Perfect Strangers is it. And it’s a good album title too, don’t you think? Very apt; better than Smash Your Head In or something.

What finally persuaded you [Roger Glover] that getting Deep Purple back together was a good thing?

Roger Glover: Well, for six years or so I’d been vehemently against it. I went into the initial meeting we held in, at most, a kind of 50/50 frame of mind. But when we finally sat around the table, all five of us, it – this sounds stupid – but almost immediately I could detect a certain magic feeling, a definite spark of excitement in the air. So I then quickly went from 50/50 to about 70/30. And then, after we’d spent some time playing together, I became 100 per cent in favour. Really, it felt that good.

The parting of the Mk II line-up was not pleasant, it was fraught with all kinds of tensions, but it always felt... Put it this way, it’s kind of like when you’re eating a meal and someone takes your plate away and you’re still hungry. I suppose I felt, with Purple, that deep in my heart I wanted to finish that meal. But in the back of my mind I thought it might be a mistake because the meal might have turned cold.

Ha! This analogy is getting beyond me. The real reason I’m here now is because I enjoyed myself when we first met and jammed together, and I felt that, yeah, we had something good to say.

You [Ritchie Blackmore] reportedly wanted Purple’s Perfect Strangers to be as good a comeback album as Yes’ 90125. Is there any truth in this?

Ritchie Blackmore: Well, who wouldn’t want to return with as strong an album as 90125? It’s a great record, it’s got a superb sound and I like Trevor Rabin; one of the best guitar solos I’ve heard in a long time is on Owner of a Lonely Heart.

That actually moved me, it made a real change to hear someone actually doing something adventurous with a guitar instead of just running up and down the fingerboard and saying: ‘Wow, impressive, huh?’ The sound of that guitar synthesiser is also very exciting, so much so that I actually went out and bought one.

It would have been a hoot to have had Trevor Horn at the production controls for Perfect Strangers, wouldn’t it?

Ritchie Blackmore: Do you think so? I’m not so sure. We did think about various producers, but in the end we said, ‘No, let’s get Roger [Glover] to do it, we don’t want a glossy sound, we want the album to be an 80s version of Machine Head’. And I’m quite pleased with the end result. I think we’ve struck the right chord.

You obviously feel that there’s a place in the 80s for Deep Purple’s virtuoso, sophisticated rock.

Jon Lord: We feel that. When we finally managed to re-form after all those years of rumours and false starts, I must admit I began to feel quite excited – not only for myself, but for the music business. People would be saying, ‘You know, one of those classic rock bands is coming back to play and tour some more!’ That’s not an egotistical statement, just a statement of how I felt about it at the time.

I still do feel that way, in fact. I’m pleased that we’re back, because I think that, in a strange way, we can help. That sounds weird, I know. I mean just because we’re back together again doesn’t mean we’re going to change the world or anything, but it’s going to inject something just a little bit nice back into the music business. I know that might sound trite, but it’s what I believe.

Musically, do you think you’ve been ‘saving yourself’ in any way for this big event?

Roger Glover: No. I’ve always put 100 per cent into everything I’ve ever done. If you’re an artist of any kind, that’s what you always do, there’s no holding yourself back.

There were a couple of riffs that hung around in Rainbow for three or four years that we could never quite make work. We’d try and try, but nothing would ever happen with them. They were good riffs, but they just wouldn’t fit. Then, just for laughs, when Purple were rehearsing up in Vermont, Ritchie dug out one of those riffs, and, what do you know, it worked! You’ll find it in the middle of the title track of the new album. Now that’s not saving yourself. That just comes back to the ‘chemistry’ thing I was talking about earlier.

Purple is like an old love affair and ‘love’ can be very close to ‘hate’. We’ve had our good and bad times and yes, I’m sure that this will be the case once again this time around. But there’s got to be friction; there’s nothing worse than being surrounded by a bunch of yes men, yessing themselves to death. Friction was the thing that caused this band to split in 1973, but friction was also the thing that gave us the success we enjoyed in 1973.

Like I say, it’s love and hate. When it’s love it’ll be really good, when it’s hate it’ll probably be disastrous.

Postscript: Roger Glover’s words were to prove uncannily prophetic. Despite a successful – though rainy and mud-caked - festival appearance at Knebworth in 1985, the reunited Mk II Purple only recorded one more album, 1987’s The House of Blue Light, before splitting again.

The line-up briefly got back together again for a third try in the early 90s but that didn’t last either. But as we said earlier, that’s Deep Purple all over for you. Should we really have expected anything different? However, it now seems that the Mk II incarnation of Purple has finally been laid to rest, but the band lives on, with the current Mark IX lineup releasing the acclaimed =1 album in 2024.

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.