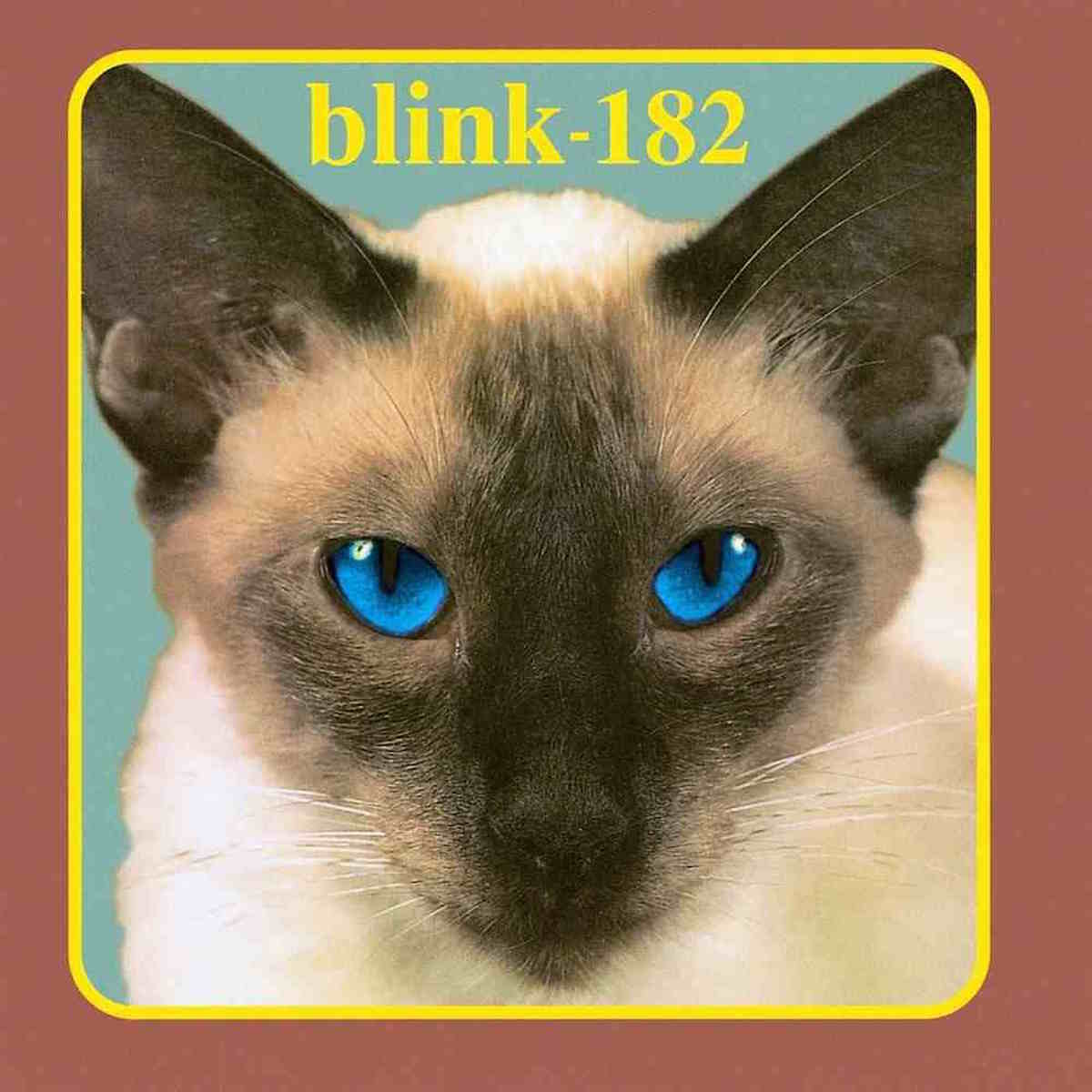

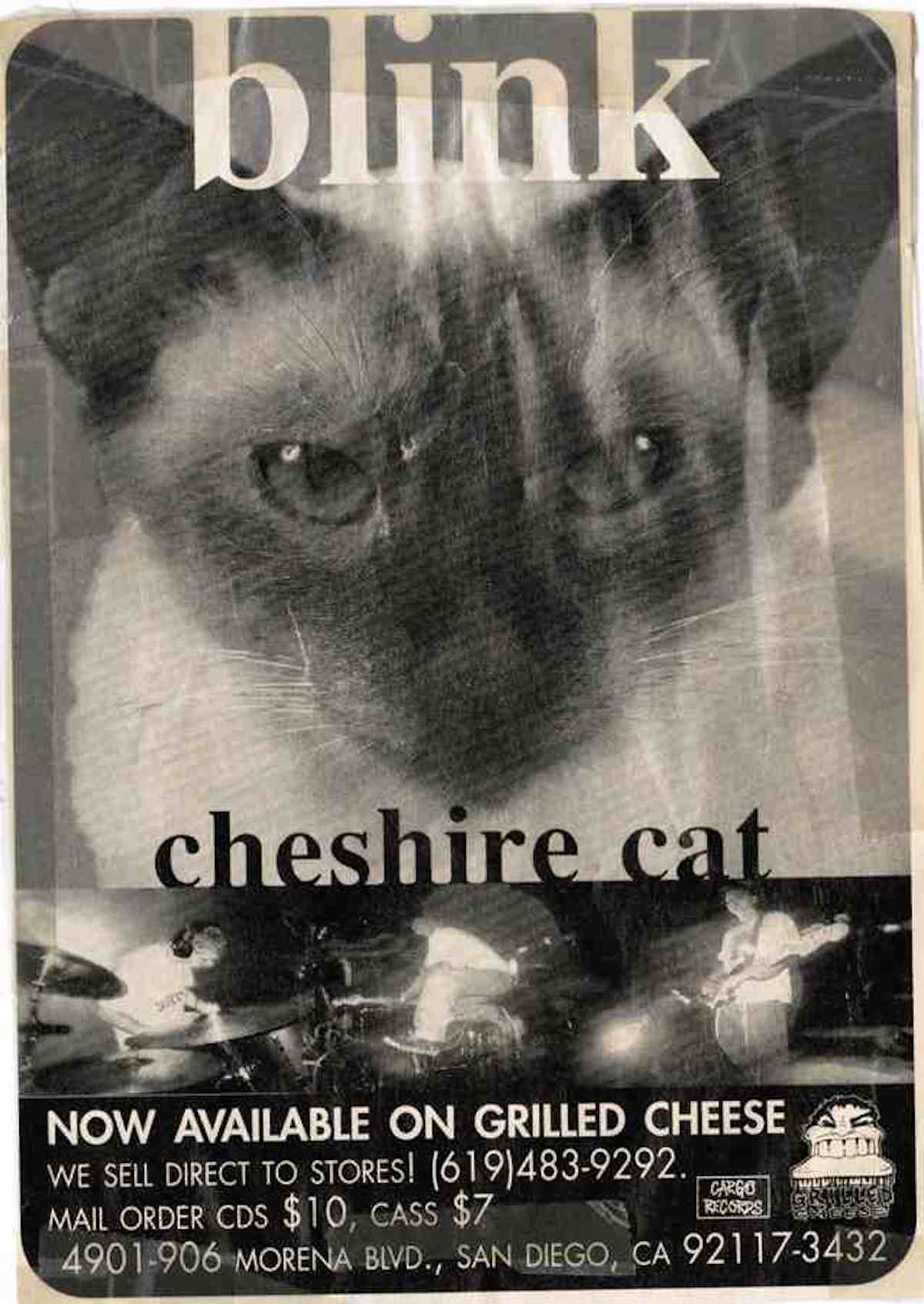

Blink-182: The Story Behind 'Cheshire Cat'

Looking back on their debut album, 20 years on...

On February 17, 1995, three skater kids from the suburbs of San Diego released an album - on cassette only at first - which made waves on their local scene but barely registered elsewhere. At first. Within five years, they were one of the biggest punk bands in the world - renowned for their world tours, fart gags and infectious riffs. Recorded in just three days, ‘Cheshire Cat’ was the album that started Blink 182 on the path to stardom…

Poway, San Diego County, sometime in the early ‘90s. Forty square miles of Californian suburb half an hour outside of the main city. High schools, malls and a massive aeroplane parts factory that employed most of the town.

If you had hung out there for a while at the time, chances are you’d have seen a small gaggle of skaters at some point. Baggy trousered, potty mouthed, bleached-haired and bored out their minds, they’d come rolling down the street. Skating from one end of town to the other, then back again for good measure. They had nothing to do and were intent on keeping it that way. They would buzz past shoppers, skid into department stores, skate down the aisles and pull stuff from the shelves. They would rattle across intersections, laughing and cursing in equal measure, bouncing private jokes between each other and drawing raised eyebrows as they went.

They were, in short, no different from a million other kids in a million other towns: bored teenagers in a boring town, waiting for life to begin, waiting to get the hell out. The difference was that two of those bored teenagers would, in just a few years, be a part of one of the biggest-selling punk bands of all time. And, 20 years ago today, they made their first tentative steps to making those dreams come true.

Tom Delonge, Blink-182’s future guitarist and co-frontman was a solid C-grade student. “I knew exactly how hard I had to work in school,” he told Rolling Stone. “As long as I got that C, I wouldn’t try one minute extra to get a B. I just cared about skateboarding and music.”

His parents had encouraged his interest in music from an early age, though perhaps had hopes he would head into a different territory than punk rock guitars. His first instrument was the trumpet, bought for him as a Christmas present when he was 11. They had joked that, when he got good, he could wake them up with a “reveille” – the dawn trumpet blast that gets soldiers out of their beds. When, one Saturday morning, DeLonge did exactly that at 5am – gasping and wheezing into the horn – they were less impressed.

He was not a happy kid. His older brother had joined the army and, in 1993, when he was aged 18 his father left the family too. “During my childhood, my parents would fight all the fucking time,” he said. “My dad left when I was 18 and my sister was 12. My mom lost her job at that point too. My sister was in tears all night long, wondering where her entire family had gone.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

“Right then, at that moment, I said, ‘this is fucked,’ and I moved out. I felt like I had to start my life and my mom and sister were asking, ‘What happened to our family?’ My older brother was off fighting wars and shit. It was horrible.”

He would later draw on the situation in Blink 182, penning Stay Together For The Kids about that time. “All of that song was describing a situation in my mom’s apartment – the shades were always down, it was really dark in there and she was probably suicidal to a degree – her kids had left, her daughter was crying, she had no job or money, my dad had another relationship going, all this fucked up stuff.”

That would come later, but in 1993 all he wanted to do was escape, bury his feelings and move on. “For so long I used to walk around saying, ‘Fuck you’ to everyone because I thought it was funny,” he said. “The shit I did as a teenager, I should be in jail for.

“This is the dumbest story but someone who belonged to my church had this big chicken farm and he and his wife were so nice. We would go out there every once in a while and play on their land. Me and my friend went through and took all these eggs and pelted all the chickens with their own eggs. We thought it was funny because they were in these cages covered in their own foetus. It was disgusting. It’s haunted me forever – the idea of doing something like that to someone who was so nice. But that’s nothing on the list of shit that I’ve done.

“There was another time. The people who lived behind me had these goats who were tied up on ropes. Whenever I’d pick up my dog shit in the yard, I’d throw it over the fence onto the goats. I thought that was really funny. The goats were covered in dog shit. They asked me if I did it and I said no. I never felt bad about that one because I thought it was pretty funny.”

DeLonge already been thrown out of High School – he was caught going to a basketball game drunk – and had already started making music. In Junior High he had upset his mother by penning a song called My Mom’s A Transvestite. Chiefly, though, he would spend his time pissing his dad off. Increasingly, it was punk rock that he wanted to play.

Mark Hoppus’ parents divorced when he was in third grade and it messed him up. He had moved around the country, living in Washington DC and in California as he spent a few years living between his mother’s house and his father’s. Eventually, he lived permanently with his dad – a missile designer for the Department of Defense –in Monterey. His sister stayed with his mother. It was a lonely existence with his dad. His father would leave for work before he got up and then would return home late, with Hoppus finding solace in music – The Cure, The Smiths. “Just Like Heaven was the first Cure song I ever heard,” he said. “A friend of mine called Wendy Franklin played it for me when I was in Junior High. Before I heard this song I was all over the place musically. I didn’t like anything specifically but, as soon as I heard that, I fell in love with music.”

He moved onto punk rock, discovering Dag Nasty – “Wig Out At Denko’s encapsulates everything I love about punk-rock in one song” – They Might Be Giants (“the first band I saw live”) and particularly the Descendents: “After The Cure, they changed everything again. One song, Silly Girl, made me want to play music as opposed to just listen to it. It was like punk rock meets The Beach Boys – it was catchy and about things I cared about, like food, girls and having a good time.”

He was a smart kid, more of a committed student than DeLonge. He headed to San Diego to college, moving back in with his mom who lived there and reconnecting with his sister who had discovered punk rock too. She also happened to be dating a friend of DeLonge’s. She knew that the guitarist wanted to start a real band and she put her brother in touch with him. Two days later, the pair were making music in DeLonge’s garage. “He was funny as shit,” said DeLonge. “The first time we played together, he climbed this lamp-post for no reason, fell off it and fucked his ankles. He was wild.”

Right then was, in some ways, year zero for pop punk. Green Day’s Kerplunk, released in 1992, had shaken up the scene. The Offspring’s Ignition also came out in 1992, Rancid’s self-titled debut was primed to emerge from the ashes of Operation Ivy in 1993, while Social Distortion and Bad Religion were both signed to major labels. In Southern California, if you weren’t into the nascent nu metal scene, you were listening to punk or ska. Hoppus and DeLonge were no different, the music fusing into their love of skateboarding, goofing off and pissing around.

They got together with a local drummer they had met at a battle of the bands contest, Scott Raynor, and hacked out a rough demo in his bedroom from the early songs they had written. It was good enough to get them a gig at The Spirit Club in San Diego. The venue was part of the very fabric of San Diego’s music scene, a key spot for touring bands and local bands. On a packed night, it officially held up to 600 people – sweaty and crushed in next to each other, heaving and howling at the bands onstage. There were two people there when DeLonge, Hoppus and Raynor, then known as just Blink, hit the stage. “We sucked,” said Hoppus later.

But it didn’t deter them. For three years they gigged locally, hung out and had fun. “We were out all night skateboarding,” said DeLonge. “We were out throwing food and drinks at security guards who were chasing us through malls, skateboarding at four in the morning, eating doughnuts at places, breaking into schools and finding skate spots in dark schools or slaloming down parking garages naked and shit in downtown San Diego. It was an incredible existence during those years and I think that was absolutely the foundation of what this band was.”

Hoppus was the most grounded of the band, still working in college. “He was always really intelligent,” said DeLonge. “I always thought it was funny that I’d go skating and tell fart jokes with this guy who was at school reading Japanese literature.”

They pieced together three early demos – Flyswatter, Demo No2 and Buddha – which, though rough-hewn, grew in confidence and style. Slowly but surely, they became embedded in a burgeoning San Diego punk scene. They gigged constantly – DeLonge would phone up schools hoping to play for the pupils at lunch time by claiming Blink were a “motivational band with a strong anti-drugs message” – and as Green Day’s Dookie exploded the punk pop scene to an international level, they found increasingly that they were in the right place – southern California – at the right time, playing the right music and doing it with the right attitude: without a care in the world.

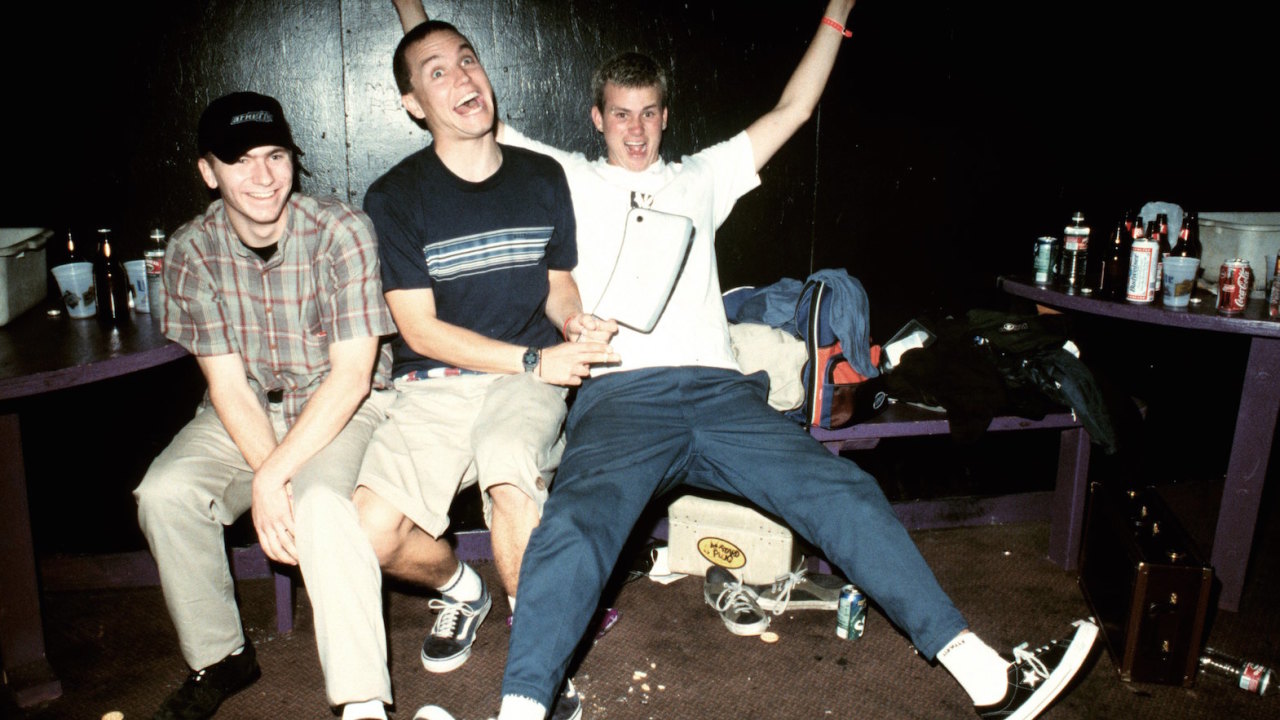

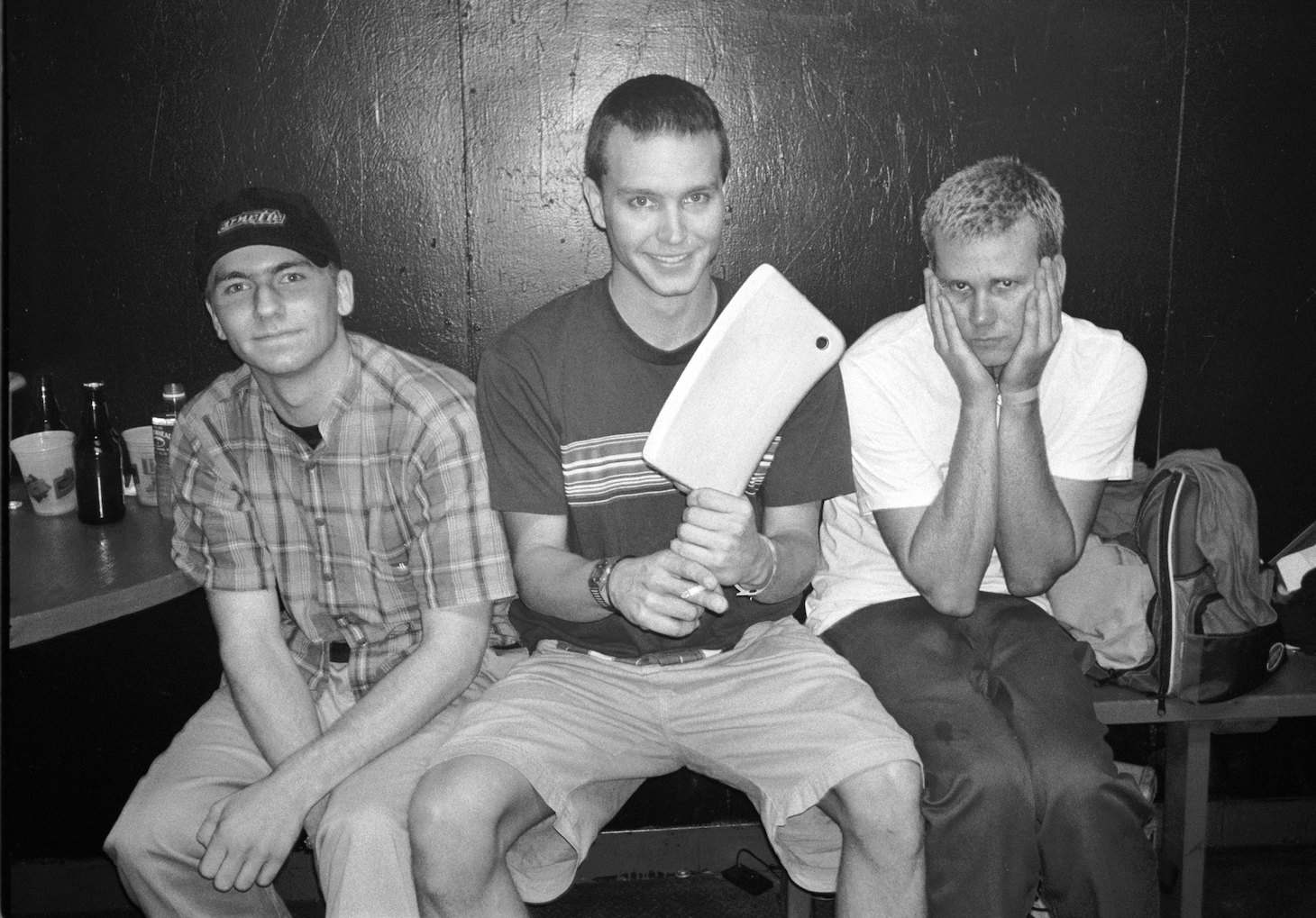

Blink-182, 1996 (from l-r): Scott Raynor, Mark Hoppus, Tom Delonge Photo: Jim Steinfeldt/Michael Ochs Archives

Cargo Records was at the heart of that San Diego scene, a local label putting out albums from bands like Rocket From The Crypt and Drive Like Jehu. Another of their acts was Fluf, whose guitarist O saw some potential in Blink and mentioned them to the label. Meanwhile Cargo’s owner’s son was also a fan and he persuaded his father to come watch them. His dad was impressed enough to offer to put out a single.

But Blink wanted more than that – they wanted to release an album, something Cargo could either not afford or didn’t want to risk for such a small, local act. But then the band told the owner, Eric Goodis, that they could pay for the recording time themselves. Goodis changed his mind and offered them a deal to release a full length – one which only Hoppus signed as DeLonge was at work and Raynor still a minor.

It wasn’t long before the band were in Los Angeles, lost, and searching fruitlessly for Westbeach Recorders, the studio set up by Bad Religion’s Brett Gurewitz on Hollywood Boulevard. Eventually after arriving three hours late – an issue because budget constraints meant they only had three days to record and mix the 16 tracks they had written for the record – they started work immediately, laying down drum tracks almost as soon as they arrived.

Grinning from ear-to-ear, they raced through the tracks, thoroughly enjoying the experience of being in a real studio. They cracked jokes, they farted, they had a wild time and they put in three 12-hour days to get it all done. The three of them stayed in a nearby hotel, all sharing one king size bed, shovelling down Chinese food, then heading back to the studio. The results were joyful, immediate and full of the relentless energy that went into their recording. But they were also a mess.

DeLonge and Hoppus were disappointed and Steve Kravac, who engineered the sessions, told them they needed more time to do some overdubs. They booked into San Diego’s Doubletime Studios – where they had recorded their last demo Buddha – and mixed as they went along. This time, they were delighted with the results.

“Every song of ours is a version of another punk song that I’ve heard and tried to make better,” DeLonge said at the time. “In the end, ours wind up a little different, but I know where the influence came from, and I think it’s important to acknowledge that.”

Cheshire Cat came out on February 17, 1995 – 20 years ago. It was initially released only on cassette but was later put out on CD and vinyl. It was riddled with the band’s infectious and undoubtedly puerile humour, featuring songs about masturbation and fucking around, as well as tracks about the rest of what defined their lives: relationships, girls and hanging out. It was an adolescent album written by adolescents and for adolescents. It was meant to be fun. And though it was by no means polished, it was exactly what it set out to be: a riot.

“We thrive on this whole concept of not growing up … of the older you get, you should still think young,” DeLonge told the LA Times. “It’s who we are … and although I don’t always succeed, I try to put a funny, clever twist on things.”

The first single, M+Ms, became a local radio hit – bringing it to the attention of an Irish techno band also called Blink. They threatened legal action unless DeLonge and co changed their name and so ‘182’ was added at random to make the band Blink 182. And from then, things picked up quickly. A manager, Rick DeVoe, picked them up and then so did a booking agent and soon they were touring for the first time outside of San Diego – travelling the country in a convoy of cars then finally their own tour van and even making it as far as Australia.

It was the start of a career that would go on to spawn the sale of millions of records, of equal parts fart gags and pop punk brilliance. Though Raynor would go on to leave the band, the other two adolescent kids who made Cheshire Cat would become two of the most successful rock stars in the world – headlining festivals, stadiums and mammoth world tours. It all started with three bored kids messing about after they had finished skateboarding through town.

Tom Bryant is The Guardian's deputy digital editor. The author of The True Lives Of My Chemical Romance: The Definitive Biography, he has written for Kerrang!, Q, MOJO, The Guardian, the Daily Mail, The Mirror, the BBC, Huck magazine, the londonpaper and Debrett's - during the course of which he has been attacked by the Red Hot Chili Peppers' bass player and accused of starting a riot with The Prodigy. Though not when writing for Debrett's.