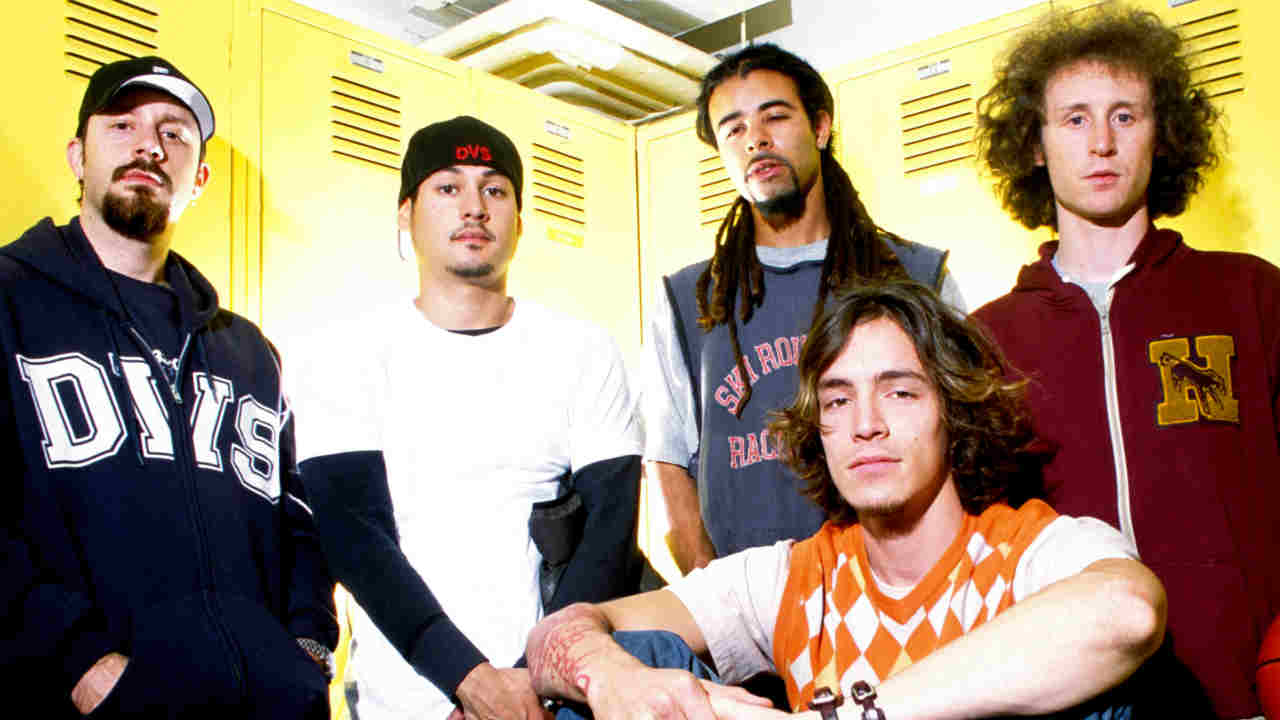

It was the video for Ari Ari that catapulted Bloodywood to the next level. It wasn’t just the visuals of singer Jayant Bhadula riding a horse through the busy streets of New Delhi, or Karan Katiyar playing guitar atop a camel, but their unique, euphoric sound. Fusing nu metal with traditional Indian instrumentation and inspirational lyrics, some in Punjabi, it was a heart-swelling, three-minute experience that marked the band out as a unique proposition. ‘’Cause the desi boys know that diversity’s a gift / And we wanna share it with our people worldwide,’ declared rapper Raoul Kerr. They had previously released metal covers of mainstream pop songs, but this was something new, and reached more than 10 million people on Facebook.

“We had gotten numbers before that on a couple of videos, but what really changed was when people said that this is something they’ve never heard before,” Karan explains today, speaking from his studio. “The covers that we did before were well-known outside India. The point behind Ari Ari is it’s a cover of a folk song that is not very well known outside India. We wanted to do that so we’d know that it’s the sound that’s pushing it. So that’s when we knew that OK, this is the sweet spot.”

- The 50 best Metallica songs of all time

- The Story Behind The Song: In The End by Linkin Park

- Slayer's Tom Araya: My Life Story

- Revenge of the freaks: the rise, fall and resurrection of nu metal

To their surprise and delight, Bollywood star Ileana D’Cruz shared the video with her 12 million Instagram followers, giving them the kind of media exposure that usually comes with a hefty price tag.

“We were excited because metal bands in India don’t get attention like that at all,” smiles Karan. “And all the record labels are basically tied to Bollywood. So if you ask any pedestrian in India, ‘What is your favourite song?’ the person would probably tell you the name of a movie first, and then the name of the song after that. Songs are considered a part of movies. So it was a very huge deal for us. We weren’t pushing to get into Bollywood, but it was just getting that nod of approval, if you will, from the biggest music industry in India.”

It’s a sound that’s carried them from bedroom band to Wacken alumni – a journey you can see in Raj Against The Machine, the new documentary named after their first, and so far only, tour. The band’s origins lie with Karan, who started teaching himself guitar in 2008, inspired by the likes of Linkin Park and As I Lay Dying, before falling down “the rabbit hole of thrash, death and doom”. He would upload metal covers on YouTube under his own name and played in local bands, which is how he met Jayant in 2015, who sang for tech metallers The Cosmic Truth. The duo transformed Bollywood song Sinbad The Sailor into the more tongue-in-cheek Sinbad The Slayer, and were over the moon when the original composer shared their parody video.

But when Karan quit his job as a corporate lawyer at Clifford Chance that year, he didn’t tell his parents he was pursuing his metal dreams full time. Instead, he would secretly track cover songs at the family home in New Delhi, and then, afraid they would find out he was doing “some kind of weird stuff that involved people screaming”, decamp to a friend’s studio for a few days to record with Jayant. To keep warm at night, the pair would sleep on the floor wrapped in a curtain.

“They always saw me running off with my guitar somewhere, even when I was in college or working. They thought, ‘Yeah, he’s in some band, it’s a hobby,’” Karan explains. “When I quit my job, I told them I was going to work on a start-up.”

They named that “start-up” Bloodywood, and in 2017 gained significant traction with their joyous cover of Mundian To Bach Ke, Panjabi MC’s hit that had swept charts worldwide in 2003. In the meantime, Karan was making music videos on the side. His lyric video for Nepalese band Underside brought him to the attention of rapper Raoul Kerr, who asked him to film a clip for the song For Her. With his shaven head, tank top and ripped physique, he cuts an intimidating figure, but the song actually speaks out against rape culture and victim blaming. Impressed by his lyrical composition and delivery, Bloodywood brought him on as a guest for Ari Ari, and he’s stayed with them ever since.

“We met at Khan Market, near my house. He came to meet me at 10pm; he was standing right under the lamppost, with shadows under his eyes, and he looked like a daunting figure!” Karan laughs today. “I didn’t expect a guy like him to ask me to make a video for his rap song, but he was very chill.”

Finally finding their feet, Bloodywood put out two original songs, each with a message. Stirring, heartfelt and earnest, Jee Veerey (‘Live, Brave One’ in Punjabi or Hindi) is about dealing with depression, and on release the band offered 60 pre-paid counselling sessions for fans. Meanwhile, Endurant comments on bullying. It’s clear Bloodywood are on a mission to promote togetherness, and empower people to overcome adversity.

“I think it’s the need of the art, to be honest,” says Karan. “To speak about things that are less spoken about. It’s much better now in the West, but it’s still not where it should be. But it’s really, really bad in India. I think I read somewhere that percentage-wise, we’ve got the most depressed people in the world, and no one talks about it. At the end of the day, we want to create a positive impact with our music.”

It was after releasing their own material, and while planning their first tour, that they got the call from Germany’s legendary Wacken festival. Elated but apprehensive, the pressure was on to make Bloodywood stage ready, and to recruit other musicians to round out their line-up. While Karan admits none of the band are disciplined by nature, they developed an insane practice regime where they played each song for a total of 20 hours, the whole set for 20 hours, and the whole set with onstage movement for 20 hours. They also performed a small, unadvertised club gig, before hiring an empty venue to perfect their set-up.

“By the 18th or 19th hour of everything, we were really nailing it! It became second nature to play the songs and understand how we’re moving around, and what signals to catch. Because of that very nerdy approach, it really helped us a lot,” admits Karan. “Wacken doesn’t just invite a band that’s never played live before to play at Wacken, so it was a huge deal for us. We didn’t want to disappoint anyone.”

Karan describes the experience as “terrifying”. Not only would they be playing their first shows, and with new gear, it was the first time he and drummer Vishesh Singh had left India.

When they arrived at Wacken’s W.E.T. stage for soundcheck, ahead of their 1.45pm slot, the crowd was sparse. But by the time the curtain came down, there were thousands of people chanting Bloodywood’s name. “Sometimes there are these rare moments where you feel it was all worth it,” smiles Karan. “When you feel that all that you’ve done has culminated in this one particular moment. And it was honestly life-changing. It’s one of those things I still get goosebumps thinking about.”

In Bloodywood’s documentary, you can see the crowd and the band feeding off each other’s energy. Not only are the band throwing everything at their opportunity, there’s the powerful, shifting dynamic between Jayant’s singing and Raoul’s rapping, Karan’s soulful tin whistle interludes, and the constant, percussive, geographically distinct sound of Sarthak Pahwa’s dhol.

“The dhol is very, very common in north India,” explains Karan. “You will hear it at every celebration. Weddings for sure, and if your kid’s having a birthday and you want to call some traditional musicians, the dhol will always be there. Diwali festivals. Even if a politician is standing up to put his name in the list of candidates, he’ll get this huge rally of dhol players behind him. So the dhol is basically an instrument that’s extremely loud, and it can be louder than an entire drum kit. It’s iconic to the Indian sound.”

The band had a few mishaps on tour – including a situation in Russia where they had to evacuate their hotel during a hurricane, knee-deep in water, carrying their gear, while drunk – but ultimately it was a triumph, and a testament to their imagination, perseverance and positivity. In keeping with their generous spirit, they used the profits to buy an animal ambulance for charitable organisation the POSH Foundation, and released Yaad (Hindi for ‘remember’ or ‘in memory’), with a video about what it’s like to lose a beloved canine friend.

They’re currently hunkering down to record their debut album, and even have an offer to write a song for a Bollywood movie. Karan’s parents are now in the loop and, thankfully, they’re as supportive as Bloodywood’s growing legion of fans.

“Whenever a relative comes, my mum forces them to watch our entire Wacken set from the beginning! Ha ha ha!” laughs Karan. “Indian parents rarely ever, rarely ever tell you that you’ve done a good job, or they’re proud of you. But you get to know that through their actions.”

Bloodywood’s documentary, Raj Against The Machine, is available on YouTube