50 Years Of Pink Floyd: Floyd's Absent Album, 1975

Nobody home

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

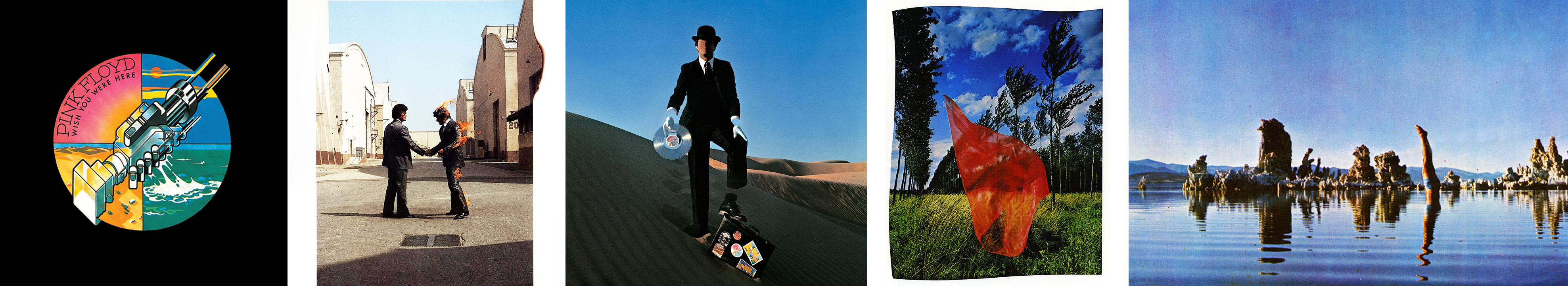

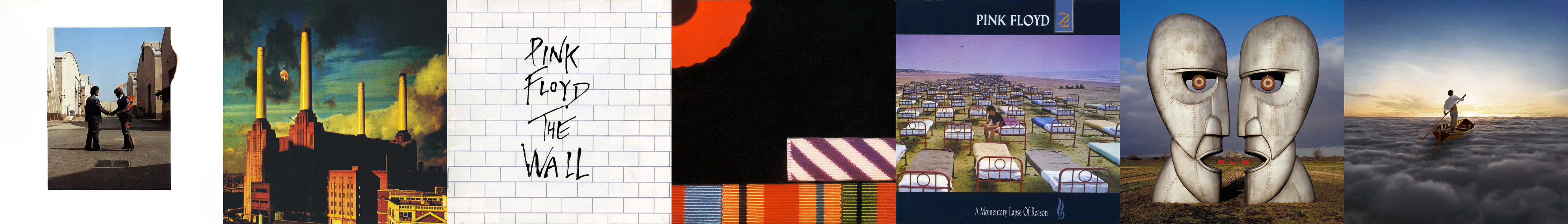

Wish You Were Here was made by a band that wished they were somewhere else. So for the sleeve, designers Hipgnosis created images that reflected the mood of absence and uncertainty.

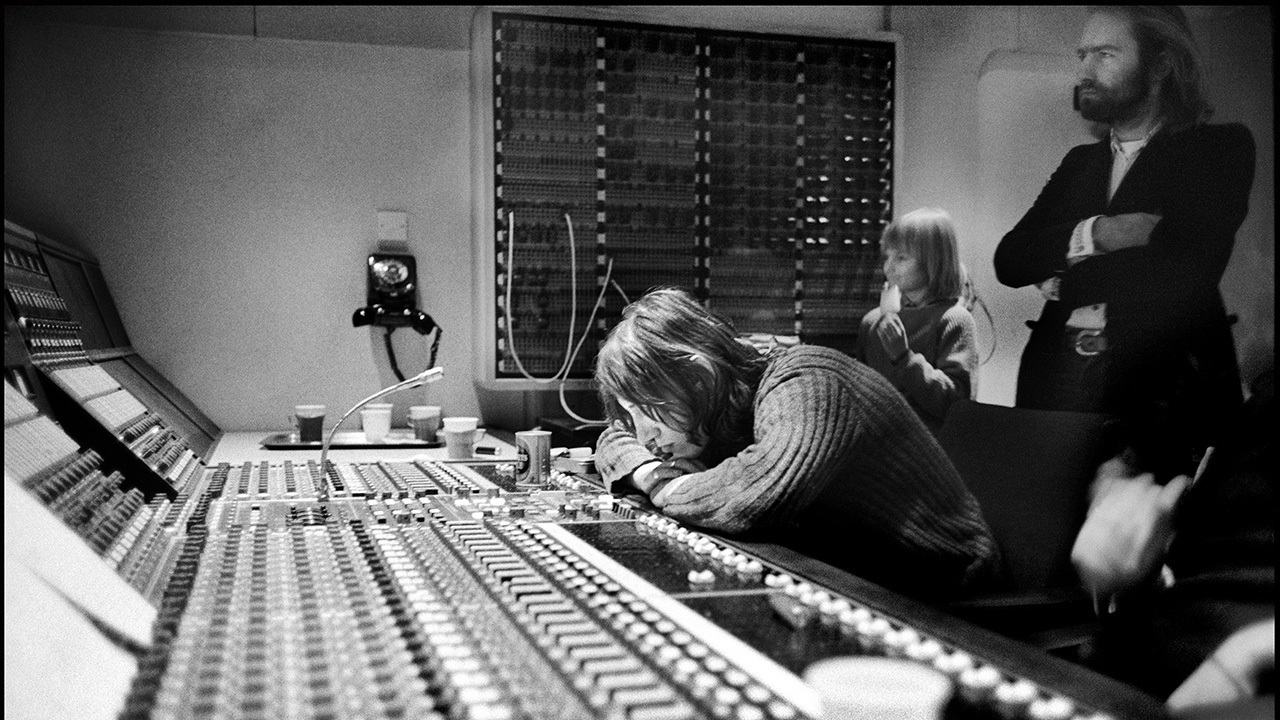

They were not entirely together as a band,” recalled Storm Thorgerson, Pink Floyd’s album designer, talking about when he watched the band recording Wish You Were Here in 1975. “I heard a lot of the music. I was there all the time as the Abbey Road studio was very near to my house. They did a lot of talking to try and work out what was going on. Roger, who was usually quite clear about things, didn’t have a clue either. It took a long time to find the theme.”

According to Thorgerson, who died in 2013, the key word was ‘absence’. “An absence of Syd Barrett, and to some extent an absence of commitment from the band themselves,” he explained. “Having been extremely successful with Dark Side Of The Moon there might have been a great temptation not to go to work. If it wasn’t for the fact that Roger was the driver and the motivator they might not have gone back to work.”

Along with the unspoken theme of absence that pervaded Wish You Were Here, the follow-up to Dark Side Of The Moon, the album also reflected a more direct sense of disillusionment with the record industry. This was especially pertinent on two of its tracks: Welcome To The Machine and Have A Cigar.

As Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell, Thorgerson’s partner in the Hipgnosis design company, put it: “The album is primarily about absence and about their disenchantment with the music business and record company executives – one of whom really did ask the group: ‘By the way, which one’s Pink?’ And they’d be asked so many stupid things like that. The business of the record companies at that time was far from scrupulous, and songs like Have A Cigar are very much a comment on the times.”

As Pink Floyd’s album designers from 1968’s A Saucerful Of Secrets onwards, Thorgerson and Powell had, with the band’s connivance, succeeded in leaving off both the group’s name and the album titles on their covers, and using a photograph of a cow (Atom Heart Mother), an ear (Meddle) and a prism (Dark Side Of The Moon), much to EMI’s chagrin. But the dramatically increased sales of each Pink Floyd album brooked no argument. If there was a budget for the cover shot for Wish You Were Here it was never mentioned, in the same way that no one was telling Pink Floyd to “get a move on” in the studio.

So it was that Thorgerson and Powell found themselves in California, musing on how to convey absence on a record cover.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I didn’t know what to do,” Thorgerson remembered. “It took about six weeks – which was a long time – as I looked for a theme. I got very preoccupied with the number four; there are four members of the band, there are four words in the title and there are four elements to life. So I used earth, water, wind and fire as a sort of location, working through what the picture would be.”

First up was water. “Po found this fantastic location called Lake Mono. It was amazing,” Thorgerson says. “You could just about photograph a plastic duck in it and you’d like it.” Instead Powell photographed a man diving into the lake but apparently leaving no splash or ripples, as if he wasn’t really there – as if he was absent.

“The guy is doing a yoga position in a yoga chair locked into the mud,” Powell explained. “He had breathing apparatus, but he had to hold his breath so I didn’t get any bubbles. That’s all shot for real, it’s not airbrushed or cut in or anything.” The picture was used on postcard, with the words ‘Wish you were here’ printed on the reverse, that dropped out of the LP cover when you took the inner sleeve out.

Next came fire. “I had this image of a burning man, who was on fire because he was frightened of being burnt because he had been left before so he was absented,” claimed Thorgerson. “Our illustrator George Hardie thought it would be a picture or an illustration, but I said: ‘Oh no, it’s real.’ Everyone thought it was an outrageous idea, particularly in the days before computers. It meant setting a man on fire, which we did.”

Thorgerson and Powell devised an image of two businessmen in suits shaking hands, with one of them alight, and set up the shoot in a back lot at Warner Brothers studios in Burbank, California.

“I got a very famous stuntman called Ronnie Rondell,” Powell recalled. “He worked a load of James Bond films, and he still says: ‘Everybody knows me for that fucking album cover.’ He had a special suit covered in inflammable liquids, and we had a crew to put him out. I shot about six takes, because the fire was so incredibly intense. He was wearing this suit and this wig, and on the seventh take the wind blew all the fire in his face and he got burned and wanted to stop immediately. I had the shot, though. Then when we came to preparing the shot for the cover we decided to put it in a frame and just burn the edge of the image, as if the fire had actually taken hold of the album.”

Thorgerson was particularly pleased with the cover image. “Because somehow the man is appearing not to pay any attention, which in a sense is impossible. How can you not be concerned about being on fire? It may not be entirely clear what the meaning is, but I think that ambiguity is quite good because it can mean different things to different people.”

The back cover featured, in Thorgerson’s words, “a faceless Floyd salesman selling his soul”. It was shot in California’s Yuma Desert, and the salesman’s wrists and ankles were removed to signify an empty – absent – suit.

The final element, wind, was depicted on the inner sleeve with a picture of a red veil floating on the breeze, behind which, if you squint hard enough, is a naked woman. In a rare burst of frugality, Thorgerson and Powell ventured no further than Norfolk to find a suitable wood as a location.

All that was left, then, was for the album to absent itself. Thorgerson had toyed early on with the idea of a blank white sleeve: “But of course The Beatles had already done that [with 1968’s White Album.” However, while browsing in a California record shop he noticed that Roxy Music’s recent album Country Life, featuring two scantily clad girls on the cover, had been covered up by their prurient American record label with an opaque green shrink-wrap and sticker. It was a short step from a green shrink-wrap to a black one, on to which a sticker with the image of a George Hardie-designed mechanical handshake (an empty/absent gesture) was applied.

When Thorgerson and Powell presented the complete album package to the band they were given a spontaneous round of applause. EMI had already been beaten into submission, and were just grateful that the sticker featured the name of the band and the album title. However, in the US the band had just signed to Columbia Records, who were less than happy with the idea, and had to be talked down.

But when Wish You Were Here was released in September 1975, the biggest absence of all was Pink Floyd. Following up Dark Side Of The Moon had been a traumatic and exhausting experience. They’d struggled for months, until Roger Waters called a halt to proceedings, ditched two of the songs they’d already road-tested (much to David Gilmour’s annoyance) and replaced them with Welcome To The Machine and Have A Cigar. That, in turn, revived their new epic song, Shine On You Crazy Diamond, which was then split to bookend the album. Elsewhere, the wistful title track was perhaps the last truly great collaboration between Waters and Gilmour.

While making the album, the sudden, unannounced appearance at Abbey Road of the Crazy Diamond himself, Syd Barrett, now bloated, bald, unrecognisable and, according to Thorgerson, “not really there”, had shaken them all to the core. They never saw him again.

Success had also taken its toll, personally and professionally. Roger Waters had got divorced, Nick Mason’s marriage was crumbling, and Rick Wright was getting delusions of grandeur as lord of his newly acquired country manor house. Only Gilmour had remained earthed, settling down and marrying his American girlfriend, Ginger.

Touring as megastars had also been a rude awakening. Pink Floyd had previously performed to rapt, attentive (ie, stoned) audiences. Now their gigs had turned into an excuse to party, particularly in America, where the whoops and firecrackers could sometimes drown out the band’s meticulous music.

Tellingly, once they’d finished recording Wish You Were Here the members of Pink Floyd scattered. They would not be seen together in public for over a year. It was the beginning of the end.

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.