You can trust Louder

The premise for this album was simple enough: reunite the band that recorded Santana III back in 1971 and proceed as if nothing untoward had happened. It sounds extremely appetising, particularly for those who were swept away by the thrilling Latin-rock style that Santana pioneered at the end of the 60s.

But, naturally, it’s not quite as straightforward as that. For a start, three members of the Santana III line-up are missing. Original bass player David Brown died in 2000 and Coke Escovedo (who was not yet a full bandmember, although his percussion is all over Santana III, along with a special thanks on the album credits) died in 1986. More relevantly, the still-living percussionist and founder member José Chepito Areas has not participated this time around for undisclosed reasons. Indeed, none of them are mentioned anywhere on the album notes, which is disappointing.

Secondly, the band that made Santana III disintegrated publicly, noisily, messily and traumatically for all involved, the result of being showered with instant fame and fortune. The gang mentality that had spawned them was ripped apart by drugs and power games. It explains the exciting, intense, almost manic sound of the album as they hurtled towards self-destruction. The new line-up that emerged on Caravanserai took a deliberately refocused, jazzier direction, for better or worse.

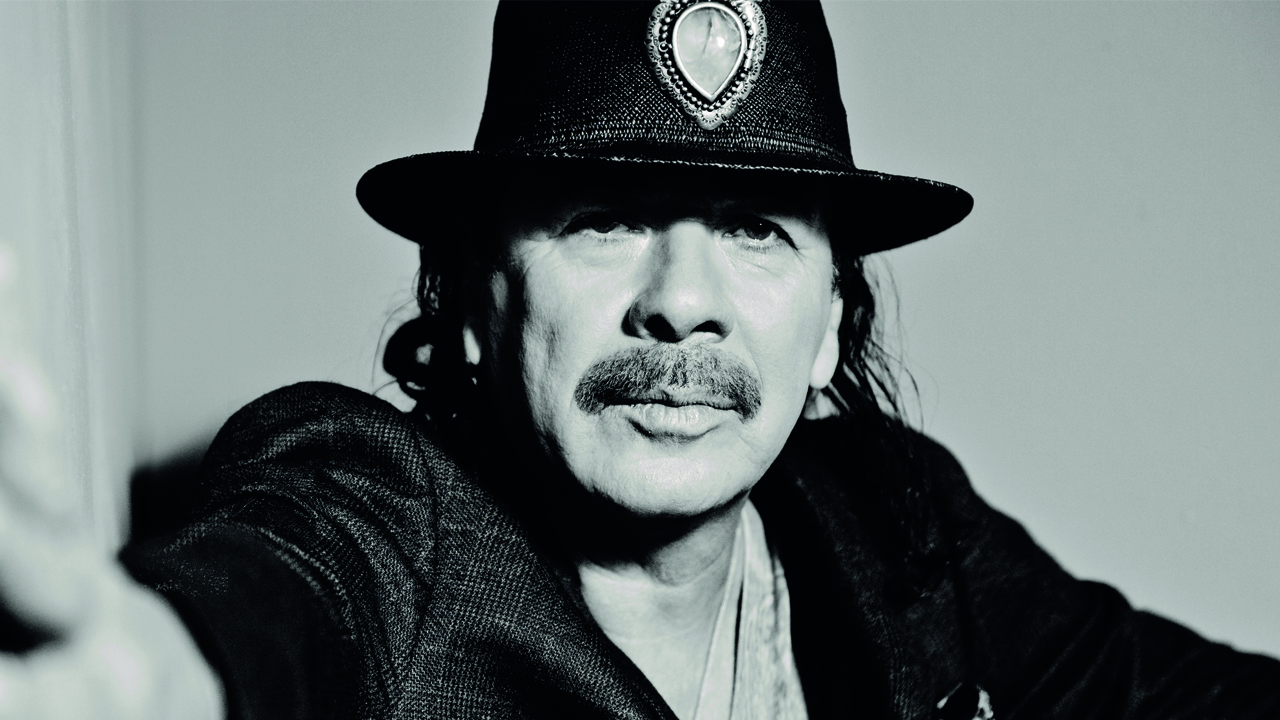

So it’s the spirit that created Santana III, rather than the sordid detail, that is being honoured by founder members Carlos Santana, drummer Michael Shrieve, keyboard player Gregg Rolie and percussionist Michael Carabello, plus the then-teenage guitarist Neal Schon (who had just joined the band and produced his own more innocent excitement for the others to rally round). Specifically, they have gone out and recreated the wide-ranging jams from which most of the songs were fashioned.

There’s an unspoken sense of “Right, where were we?” to the opening Yambu as the band settle in, the guitar noodles and gathering rhythms gradually coalesce around a deceptively simple riff and chorus. When Rolie’s gently vibrating, gradually thickening Hammond chords start cutting swaths through the sound, the picture is complete (worthy of Dorian Gray, even).

So it’s no surprise whatsoever that Shake It hardens up into something altogether heavier before Schon wah-wahs his way to infinity and beyond. But the Afro-centric rhythms offer a different thump. It sets a pattern; out of the half dozen or so elements it takes to make a Santana classic, a couple are set free to try something different. Most of the time it’s subtle, freshening up the familiar Oye Como Va or Guajira rhythms, for example, but sometimes it can give a whole new slant, as when Ronald Isley shows up on a couple of songs and gets all evangelical.

The acid test – and you can take that phrase whichever way you want – comes on Fillmore East, a tip

of the hat to their favourite venue, where a song would grow out of the tune-up and a few restless beats to become an irresistible force (except that five decades later, their chemistry is more focused). It’s one of many highlights on an album that’s so much more than Santana by numbers.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.