You can trust Louder

As the author admits, it’s a common habit for rock fans to look back on the time when music meant the most to them – usually their teens or their salad days – and proclaim that era the finest ever for rock music. Having come of age in 1971, Hepworth has a personal attachment to the year. For others, it might be 1967 or 1979. So, what’s the difference?

“I’m right,” argues the author, and proceeds, month by month, release by release, to expand on his thesis in a scientifically unprovable but entertaining, illuminating and lipsmacking way.

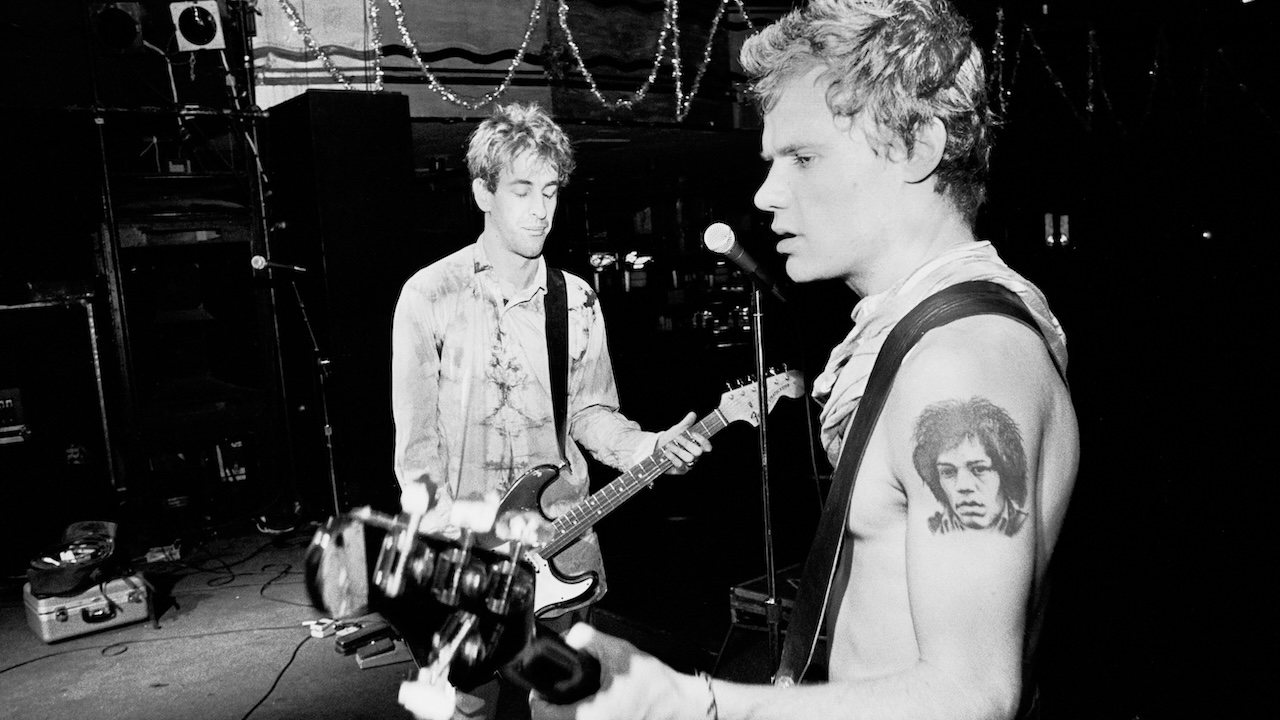

Traditionally, 1971 has a bad rap because it’s assumed that the disbanding of The Beatles left a hole in the scene, into which rolled all kinds of turgid, mouldy and metallurgic fare, the beginning of a slow decline requiring punk’s late-70s resuscitation.

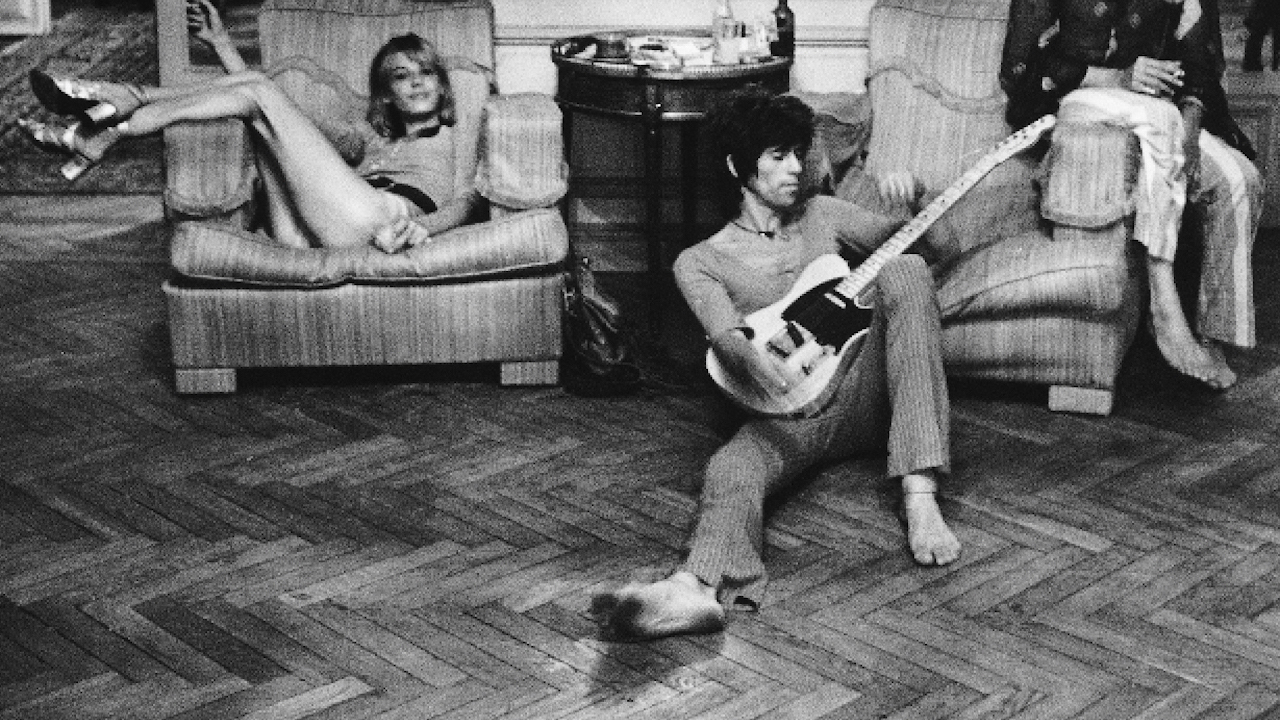

Hepworth certainly has vivid memories of 1971 as being endured; of Berni Inns rump steaks, Rolf Harris on Saturday night TV, of wartime culture still dominating the airwaves and newsstands, of the near-invisibility of black people in the UK. He also recalls the privations of gig-going, of feeling the cold of parquet floors as you sat cross-legged in cheap loon pants.

However, Hepworth also shows how 1971 was the year all kinds of great things were birthed, including the concept of rock itself – now louder, more massive, more lucrative, whose cornerstones were the likes of The Who, the Stones and Led Zeppelin. He points to Carole King’s Tapestry, rock’s first ‘evergreen’ album, its long stay in the charts buoyed up by a female audience.

He cites Stevie Wonder’s new-found electronics obsession, Marvin Gaye’s sober, groove-based What’s Going On and Sly Stone’s There’s A Riot Goin’ On as albums that would have a huge influence on black music. It was also the year Glastonbury was born, Bowie’s mind was expanded by America and Springsteen christened himself The Boss.

Hepworth has both a sense of the pre-postmodern vibe of 1971, and how it resonates, often ironically, in the present day. He might have devoted a little more space to the burgeoning Krautrock movement, but this is mighty fine and convincing read.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

David Stubbs is a music, film, TV and football journalist. He has written for The Guardian, NME, The Wire and Uncut, and has written books on Jimi Hendrix, Eminem, Electronic Music and the footballer Charlie Nicholas.