What happened the night Stevie Ray Vaughan died - by those who were there

On August 27, 1990, Stevie Ray Vaughan played the gig of his life. Just hours later he was killed when his helicopter crashed in thick fog. This is the inside story of that tragic day

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

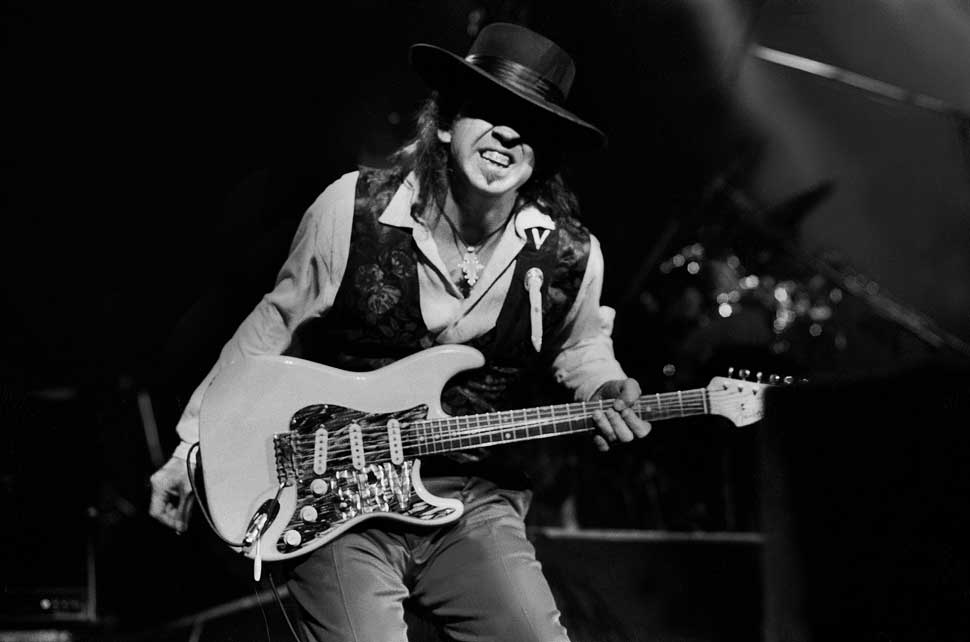

An ice-cool Texan with a Fender Stratocaster and a black cowboy hat, Stevie Ray Vaughan was one of the most influential musicians of the 80s. With his band Double Trouble, he spearheaded a blues revival during the era of Duran Duran and MTV, attracting attention from the likes of David Bowie and Eric Clapton along the way.

It was the latter who invited Vaughan and Double Trouble to support him at a pair of shows at the Alpine Valley Music Theater in East Troy, Wisconsin, in August 1990. Within minutes of leaving the venue, he was dead, victim of a calamitous helicopter crash.

Robert Knight (photographer): I was invited to Alpine Valley to do a photoshoot for Fender. I hung out with Stevie, which was great because I had known him for several years. He said, “You know, I don’t think I have much longer to live.” I asked why he would say that, and he replied, “Well, listen, I was in Switzerland and I basically had, like, an overdose in the street. I was throwing up blood. I basically died, was taken to hospital and came back to life.” He said that was when he knew he had to go sober. He said he didn’t know how much time he had left.

Skip Rickert (tour manager, Stevie Ray Vaughan): During that time, Stevie was working very hard on his rehab program. He was making incredible strides. He had been in the program for several years, and from 1985 till the day he died, he was clean and sober.

Chris Layton (drummer, Double Trouble): I remember thinking how good it was that we had put all these demons behind us. Everybody was so healthy and our future was so bright.

Eric Clapton: On the first night, I watched his set for about half an hour and then I had to leave because I couldn’t handle it! I suddenly got this flash that I’d experienced before so many times whenever I’d seen him play, which was that he was like a channel. One of the purest channels I’ve ever seen, where everything he sang and played flowed straight down from heaven.

Greg Rzab (bassist, Buddy Guy Band): I remember knocking on the door of Stevie’s dressing room. He opened it up, standing there with no shirt on, but he had his big hat on. Big hugs, “Hello, man, howya doin’?” He was in a beautiful place. He lived his last day in such a blissful state.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Nathan East (bassist, Eric Clapton Band): Stevie and I spoke briefly in the dressing room before he went on stage, saying how much we all looked forward to jamming together at the end of the night. He seemed really happy to be there and was in great spirits.

Buddy Guy: They invited me up there just as a guest, so I was sittin’ on stage from start to finish. This particular night he played incredibly well – he played licks that none of us had heard before.

Greg Rzab: There was a light around him, which I always found interesting, especially now that we know what happened. He was playing his ass off. He destroyed the audience, went crazy.

Robert Knight: Stevie had made a point of saying he was going to do a special version of Voodoo Chile, just for me. He insisted that I should shoot that. “I want you to be there.” I don’t know why. So he comes out for the encore and it’s Voodoo Chile, but as I’m shooting, both my arms turned to ice blocks and my camera felt like a piece of frozen ice. It wasn’t a cold evening.

I kept shooting for two or three minutes but I couldn’t take what was happening to my hands so, in the middle of the song, I went backstage. Stevie came off, walked up to me, and said, “Why did you leave?” I rolled my sleeves up and said, “Stevie, look at my arms.” I had goosebumps that looked like they were frosted. Stevie said, “Look at mine,” and he rolled up his sleeves and he had the same thing.

Chris Layton: Eric introduced Stevie as the world’s greatest guitar player, and when he played his first note, it sounded like he bent the string farther than there was fretboard. I got these chill bumps. It was like this thing ran up my spine.

Tad Laszewski (audience): After the encore, all those great musicians started to wave and leave stage left. The last to leave was Stevie Ray. He was known for his Texas black-rimmed hat, which he never took off. Before exiting, he removed it, waved it to the crowd and disappeared.

Sheriff David Graves (Sheriff of Walworth County): That night, visibility was extremely poor. I remember walking from the back gate of the theatre toward my car in the hotel parking lot. I could barely see the helicopters as they sat on the ground. I thought to myself, “I can’t believe the pilots can fly out of here in this soup.”

Chris Layton: Right after that last show, Stevie and I sat by ourselves on two chairs backstage and had a really long talk, about 40 minutes, about all sorts of things that we hadn’t talked about in a long time. We both had a real serenity and peace. At the same time he was really excited about the prospects for our next album.

Robert Knight: That was when Eric mentioned that Nathan East didn’t want to go in a helicopter.

Nathan East: The father of a young lady I’d just met had offered me and Eric’s keyboardist, Greg Phillinganes, a ride to Chicago in his twin-engine Cessna. That left two empty seats in the helicopter.

Chris Layton: When Stevie came back [to where they had been sitting], he had all of his bags. He said there was a space on one of the helicopters and it had been offered to him. I told him I loved him, and maybe we’d get some breakfast in the morning before we flew back to Texas. He said, “Yeah, man, but I want you to know I love you.”

Greg Rzab: Four vans took us out from the dressing rooms to the helicopters. We got out there and the weather was horrible, but the ’copters were revved up, ready to go.

Brad Wavra (production manager, Alpine Valley): I helped put them in the helicopters, and watched them change seats to balance the weight.

Greg Rzab: I went to climb into the one with Eric and Buddy, but it was full, so it was, like, “Well, man, just get into any one.” So I went to this other ’copter, and I was about to step into that helicopter when Eric poked his head out and said, “Let’s not get separated.” So they took one gentleman out of Eric’s helicopter to make room for me. He went into the other helicopter and then Stevie got in.

Nathan East: Stevie Ray took one of those free seats, along with Bobby Brooks [Eric’s booking agent], Colin Smythe-Park [our tour manager], Nigel Brown [tour security] and the pilot, all of whom died in the crash. I’m lucky to be alive because if I hadn’t taken the Cessna, I’d have been on that helicopter.

Greg Rzab: Our ’copter was Eric, his girlfriend, Buddy and me in the back, and Roger Forrester in the front. The fog and the condensation meant you couldn’t see out. Someone outside took off his T-shirt and wiped the moisture off the bubble of the helicopter but as soon as he did that, it immediately fogged over again.

Brad Wavra: I wiped down the windshield with my T-shirt and sent them up in the air with a thumbs up… and was probably the last one to see them alive.

Greg Rzab: It was about 12.30am when we watched the first helicopters take off. We could see their lights and the propellers turning. The fog was so dense that as soon as they lifted off they immediately disappeared into the fog.

Lt David Starks (Walworth County PD): The pilot [Jeff Brown], it was his first-time flight into that area, and he wasn’t familiar with the terrain. He went up vertical, probably what he thought was high enough in normal circumstances, to clear telephone poles or radio towers.

Sheriff David Graves: Stevie’s chopper never cleared the ski hill behind the resort. No one heard it go down.

Greg Rzab: We lifted above the fog and the helicopter settled down into a perfectly calm flight pattern and we flew to Chicago.

Jim Wincek (director of marketing, Lakeland Medical Center): When the other helicopters arrived in Chicago, they notified authorities. The Civil Air Patrol put two and two together and started a search.

Lt David Starks: When they got to the top of the hill, I think about 6.30am, they looked down and saw where the helicopter had impacted. It’s no more than half a mile from the back of the theatre, but you can’t see it because of the terrain. The helicopter rotor blades actually hit the ski lift cable behind the resort about three quarters of the way to the top.

When those rotor blades stopped, their energy was transmitted into the body of the helicopter, which would then start to turn and, from our measurements and observations, they were all thrown out of the helicopter as it came apart. The helicopter did not explode, but all the aircraft fuel was spread all over the area. It covered the debris, the ground and the bodies.

Tommy Shannon (bassist, Double Trouble): I didn’t find out till the next morning and our manager Alex Hodges called me.

Chris Layton: Alex was trying to be as gentle as possible, said he was with Roger Forrester, Eric’s manager, and that one of the helicopters, the one that Stevie was on, didn’t make it back. It was 98 per cent – that’s the way I remember him sayin’ – 98 per cent certain that there was no survivors.

Tommy Shannon: That’s probably the worst moment of my entire life. After we got the news, a security guard let me and Chris into Stevie’s room, and when we saw that the bed hadn’t been slept in, that’s when it started to feel real to me. The strange thing is, when we were walking in, the radio was on and that Eagles song, the one with the line ‘I may never see you again’ [Peaceful Easy Feeling] was playing. I always thought that was so eerie.

Skip Rickert: There was a private and a public funeral just a couple of days later. I tried to help out with organising the funerals. I remember sitting at Stevie’s mother’s kitchen table handling the phone calls. I remember Dr John delivering a wonderful eulogy. Bonnie Raitt and ZZ Top came. I was honoured to be a pallbearer.

Chris Layton: I remember at his funeral, when Stevie Wonder stepped up and sang The Lord’s Prayer and it was the most amazing thing I’ve ever heard. He was crying while he was singing.

Jimmie Vaughan (brother of Stevie Ray): I was pretty lost. It took me some time to realise that I had to move on and live my life. It was hard, though. Still is. A big part of me was gone in an instant. Life isn’t supposed to be like that.

Johnny is a music journalist, author and archivist of forty years experience. In the UK alone, he has written for Smash Hits, Q, Mojo, The Sunday Times, Radio Times, Classic Rock, HiFi News and more. His website Musicdayz is the world’s largest archive of fully searchable chronologically-organised rock music facts, often enhanced by features about those facts. He has interviewed three of the four Beatles, all of Abba and been nursed through a bad attack of food poisoning on a tour bus in South America by Robert Smith of The Cure.