“That whole Christian thing, it’s so wrong. We were never Christian metal”: how doom pioneers Trouble overcame chaos, darkness and misunderstanding to make their 80s masterpiece The Skull

The story behind Chicago doom lords Trouble’s landmark 1985 album The Skull – the album which helped shape a generation

Alongside Pentagram, The Obsessed and St Vitus, Chicago’s Trouble were one of the Big Four of ’70s and ’80s US doom metal. Their first two albums, 1984’s Trouble (aka Psalm 9) and the following year’s The Skull, are held up as a huge inspiration by subsequent generations of doom groups, even if their influence far outweighed their commercial impact. In 2006, longtime Trouble guitarist Rick Wartell spoke to Metal Hammer about the chaos surrounding The Skull’s creation, and its lasting legacy.

Foo Fighters mainman Dave Grohl is a massive Trouble fan. So big, in fact that he claimed that buying their debut album, Psalm 9, was on a par with getting The Beatles’ celebrated Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band record. Not only that, but Dave is credited by original Trouble singer Eric Wagner with being the catalyst for reuniting the Chicago band, thanks to his involvement with the Foos man’s Probot project, on the song My Tortured Soul, released in 2004.

“When Dave contacted me, my personal life was at a low point,” Eric told Metal Hammer in 2006. ”Trouble hadn’t done anything in five to six years, so it was Dave who got me back on track again.”

Except Eric’s personal demons weren’t new. They went way back to the 1980s, and, according to his bandmates, played a major role in shaping Trouble’s second album, 1985’s landmark The Skull.

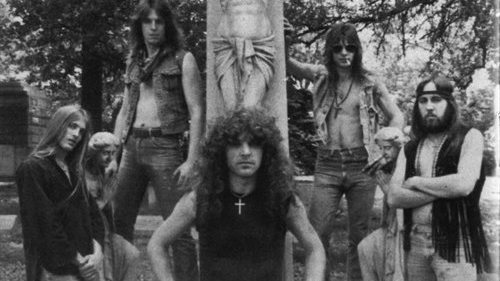

Trouble started in Chicago in 1979, featuring Eric, guitarists Rick Wartell and Bruce Franklin, bassist Sean McAllister and drummer Jeff Olson. After three studio demos and a live recording, the band got signed to the then-fledgling Metal Blade Records. The label’s 1983 compliation, Metal Massacre IV, showcased Trouble via the impressive The Last Judgement, with the band releasing the aforementioned Psalm 9 – originally self-titled – a year later.

But the real breakthrough for the quintet came in 1985 with the release of second album The Skull, although in many ways this is really a continuation of that debut.

“We had all the songs written for our first two records before we’d even got signed,” says founding guitarist Rick Wartell. “We just needed to decide which songs went on what album. We’d been touring for five years before getting the deal, so everything was honed and sharpened from the road. A lot of bands don’t even think about writing their ‘difficult’ second record until they’re forced to, but we weren’t like that.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The band went straight from touring on the back of Psalm 9 into Track Records Studios in LA to begin work on The Skull.

“Man, that was a crazy time!” says Rick. “We drove to LA from Chicago in two beat-up vans that we managed to buy with what little money we had, and then one of these broke down, so all of us were piled into one van.”

But this was the seat of luxury compared to what faced the tired mob when they made it into town. Metal Blade owner Brian Slagel was away, and his absence caused a crisis for Trouble.

“Brian hadn’t booked us into a hotel. As we couldn’t get hold of him – this was in the days before mobile phones – there was nothing we could do. We were all forced to live in Metal Blade’s office for about a week. It was horrific. The stink when we left was incredible. There were no shower facilities, so I’ll leave the rest to your imagination. We were also starving. With virtually no money, all we could do was ration ourselves to a couple of pieces of bread and one slice of lunchmeat a day – not really a rider, eh?”

The rather embarrassed Brian returned to the Metal Blade office to sort out the mess, and immediately booked Trouble into a hotel. So, problem solved? Not quite…

“The hotel was awful, almost as bad as living in that office space! I was frightened of going to sleep because of the bed bugs, and one or two others decided that sleeping in the van was preferable. But you have to realise the circumstances at the time. We were all kids, so this was an adventure and we didn’t know things were usually more upmarket! And Metal Blade were only a young label, so there wasn’t much cash around. I did hear, though, that soon after we finished The Skull, Brian moved out of his office – even fumigation couldn’t help!”

The first sessions for the album were done in the same studio where Psalm 9 had been recorded. But, on the advice of co- producer Bill Metoyer (who also worked on the debut), they soon moved to Preferred Sound, in the Woodland Hills district of LA, where much of the work was done.

“Altogether, we spent about 14 days on the album,” says the guitarist. “That may sound quick, but we did know what we were doing and had everything worked out in advance. What Bill did for us was get the sounds we wanted – he was a superb engineer. For instance, the backwards tape at the start of Fear No Evil was down to him spending ages finding the right one.”

Many Trouble connoisseurs regard The Skull as a darker and heavier proposition than Psalm 9, despite the fact that the songs in question were from the same era, so much so that, musically, Rick felt most of the tracks on these first two releases could be inter- changed. So, why the difference? To a large extent, this is due to the lyrical content, which reflected the worrying state of mind into which Eric Wagner had fallen at the time.

“Eric was in a bad way,” Rick confirms. “He’d gotten into cocaine and alcohol, and it was seriously messing him up. We had to watch as he fought those inner demons. To be honest, as long as he turned up to rehearsals and could still do his job, there was no reason for the rest of the band to get involved. Why should we? What could kids do to help? Eric had always had problems, but when we went on the road for Psalm 9, that’s when it became serious. Until then, none of us believed that Eric was effectively ill. We were so naïve back then.”

Many of the songs on The Skull, including the title track, are about Eric’s struggle with himself, and it gives the album a real sense of desperation.

“Listen to the song The Skull and you’ll hear Eric was crying out for help. The same is also true of The Wish. Those are heavy lyrics. One of the reasons we wanted to call the album The Skull was because that song perfectly captured the mood of the album.”

Some might be surprised that Trouble could stand back and watch their singer sinking into a substance-fuelled abyss, but you have to remember how young they were – and in those days, medical help was beyond their budget.

“There were times when we did wonder whether Eric was the right person for this band, and we did consider replacing him. But he’d always pull himself together. And, finally, he got out of the hole through his own efforts. Could we have done more? At the time, no. It might also have been cathartic for Eric to open his soul in the lyrics.”

But it remains mystifying how a member of any Christian metal band could get themselves into such a state. There again, mention the contentious ‘C’ word to Rick, and his reply is firm and clear.

“That whole Christian thing, it’s so wrong. We were never Christian metal” he says. “When we started, the band that most inspired us was Black Sabbath. They wrote songs about the Devil and Jesus, and used the Bible in their lyrics. Eric would do the same thing. The whole gothic thing was what we were about. We got marketed us as ‘White Metal’, which was crazy. It’s stuck with us to this day – that’s completely ludicrous.”

While we’re at it, time to dispel another rumour. It seems to have been accepted as fact in many quarters that the band weren’t getting on by the time they recorded The Skull. Again, the guitarist wastes little time in shooting this nonsense down.

“Every band has ups and downs, that’s part of the life we lead. A few years later, we couldn’t stand the sight of each other, but in 1985 we were fine. Sure, Jeff left soon after, but that was to do a music degree, and not due to a falling out. And no, he didn’t quit to be a preacher, as some people believe.”

On its release, The Skull didn’t set the metal world alight, but the passage of time has given this a vital place in metal history, with many feeling it helped to define doom.

“It is humbling to know how important people believe this record has become. I realise a lot of younger bands feel it inspired them, and I’ve been told the term ‘doom’ grew out of the style we had on The Skull.”

The frustration was that Metal Blade didn’t have the money or experience to make things happen for Trouble back then – they were a small label fighting against the major companies. But Rick believes some of the blame must rest with the band themselves.

“We didn’t push hard enough. We were getting a big buzz in Europe, and just said, ‘Whatever!’ Now I’d be banging on Brian’s door demanding that we toured Europe. But we didn’t know how things worked.”

Following the release of The Skull, Sean and Jeff left, forcing the band to replace their rhythm section. They brought in Ron Holzner and Dennis Lesh for 1987’s Into The Light, but the imagination which had defined their earlier releases seemed to have dissipated and many wondered whether the band had run their course. They effectively disappeared towards the end of the decade.

However, in 1990 Trouble signed to the Def American label, run by Trouble fan Rick Rubin, who produced their self-titled return the same year. Now with Barry Stern on drums, the band went in a more psychedelic, almost stoner direction, winning a new fanbase. The process continued two years later with Manic Frustration, which was influenced by the Beatles.

Sadly, this approach failed to gain Trouble any bigger success. They were dropped by the company, and 1995’s Plastic Green Head, despite seeing the return of Jeff, was a tired, despairing affair. No one was too surprised when Eric quit to form Lid with Anathema guitarist Danny Cavanagh, and the band was put into cold storage soon after.

Trouble reunited in 2002, releasing a new album, Simple Mind Condition, in 2007. Eric Wagner left once again in the following year, to be replaced by Warrior Soul vocalist Kory Clarke. He was in turn replaced by Exhorder vocalist Kyle Thomas, who sang on 2013‘s The Distortion Field. While they toured through the mid-2000s, shows have become more infrequent – the band’s only gig in the last six years was in October 2023 at Chicago’s Heavy Festival, with Kyle on vocal. Sadly, Eric Wagner died in 2021 at the age of 62 due to complications from Covid.

Today, The Skull remains one of Trouble’s most beloved albums and a foundation stone for 80s doom metal. “It’s my favourite of all our albums because it came closest to capturing what we were about onstage, and that’s where we always shone,” says Rick. “Sure, we became better musicians, and I love all of our albums. But there’s just something special about this one that’s stood the test of time.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer 162. Updated in March 2024

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.