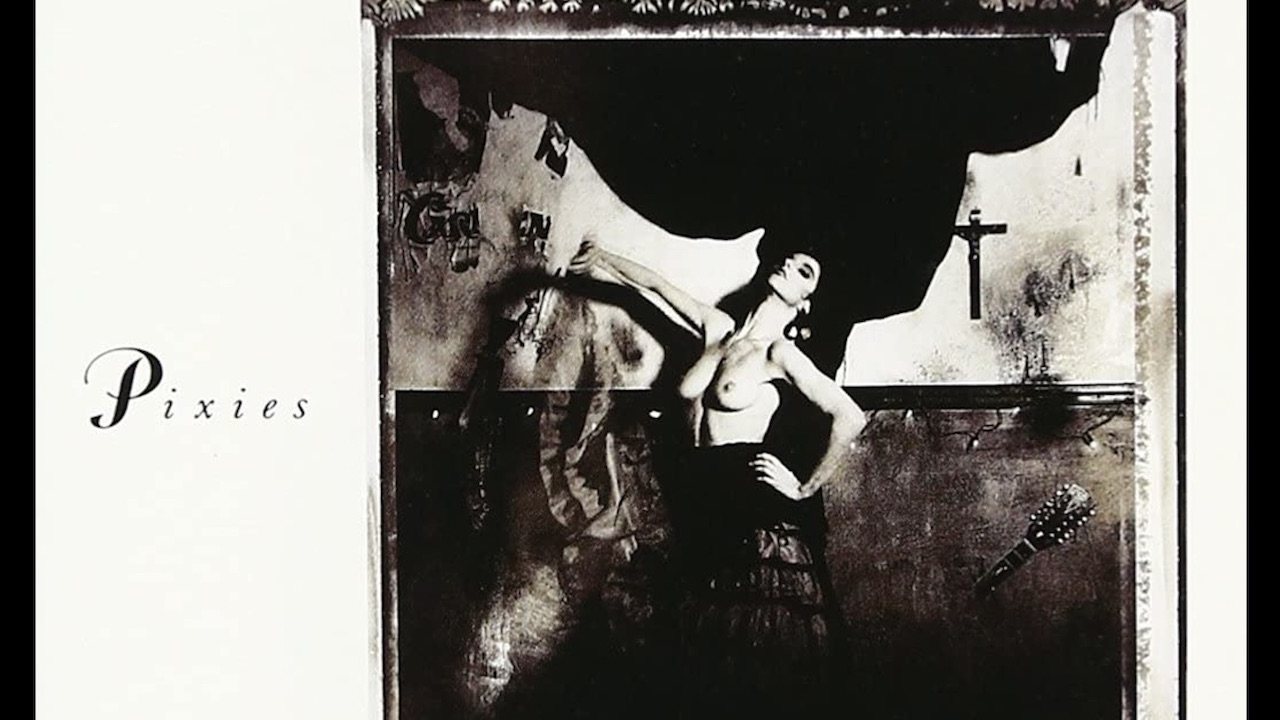

Torture. Incest. Voyeurism. Why Pixies' Surfer Rosa is the weirdest and most influential alt. rock album of the '80s

Nirvana's Kurt Cobain admitted it, but pretty much every single alt. rock band of the past 35 years has 'borrowed' from Pixies 1988 masterpiece Surfer Rosa

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Torture. Incest. Being terrorised by tiny fish. The subject matter of the Pixies’ songs on 1988’s debut full-length Surfer Rosa, isn’t exactly canon. Yet the butterfly effect created by many of them would ripple through rock music and wider cultural touchstones for decades to come.

When the oddball Boston quartet – frontman Black Francis (the stage name of Charles Thompson IV), guitarist Joey Santiago, bassist Kim Deal (then going by the stage name Mrs John Murphy, a sardonic reference to her “uncool” marital status), and drummer David Lovering – went into Q Division Studios in the winter of 1987, they did so with a green, “laissez-faire attitude”, wholly unaware of the adventures that awaited during their 10-day stay.

Having recently signed to British indie label 4AD, president and founder Ivo Watts-Russell suggested the band work with someone new, pushing them to one-up the rough-hewn Gary Smith-produced sound that debuted earlier in the year on mini-album demo, Come On Pilgrim.

Article continues belowSoon, at the mercy of ex-Big Black frontman and rising recording prodigy Steve Albini, they did just that. But not without some travails. Then in full-blown edgelord mode, and at pains to prove himself in front of “strangers” for the first time, he’d put a poster with the name of his old band Rapeman up on the walls, to mess with the studio’s daytime clients. Recording assistant John Lupfer recalls the famously cantankerous engineer making people stay until the early hours of the morning, only to go off without warning, leaving the lights on and doors open. For his part, Albini reckons the record could have been wrapped up in a week, but he instead wanted to wring every drop of juice out of the experience. Luckily, the band were game.

“I was nervous and cocky,” Albini reflected in a 2019 interview with Dazed, “and probably went out of my way to try to sound like I knew what I was doing, while the truth was that I was pretty much still learning on the job.”

“It was early in my tenure as an engineer and I wanted to validate myself and have an impact,” he told The Guardian’s Daniel Dylan Wray. “That dynamic of me suggesting goofy stuff and them going along with it was partly due to my insecurity. I’d suggest ridiculous stuff, some of it worked and some of it didn’t.”

It’s a towering record, capturing a band almost too weird for comprehension

That meant between-take banter and rumours about ‘field-hockey players’ made it to tape. Deal and Santiago played with metal plectrums. He fed Francis’ vocals on the deranged surf-rock of Something Against You through a guitar amp, creating a gnarly distortion. Most famously, all of the band’s gear and recording equipment were transported from the main studio space into the communal bathroom, where the generous natural acoustics captured a certain something in the songs’ signature quiet-loud-quiet dynamics. The huge drum sound that introduces the record on Bone Machine wouldn’t be the same without it.

And it was here where the bassist recorded the ethereal backing vocals on Where Is My Mind?, a quirky, largely acoustic track inspired by Francis’ experience while snorkelling and being chased by a four-inch fish in the Caribbean on a six-week student exchange trip to Puerto Rico (which also explains the Spanish lyrics on Oh My Golly! and Vamos). Of Deal’s puckish lead on the album’s only single, Gigantic, Albini recalls, “When she started singing, my jaw kinda dropped.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

The latter was a song that started as a source of some frustration for Francis, eventually handing it over to the creatively frustrated bassist as a challenge to finish off. All he had was a title and its circular musical motif. The initial scratch lyrics were about a shopping mall. After a viewing of the 1986 Bruce Beresford film Crimes Of the Heart, that mall became ‘Paul’, and new voyeuristic lyrics detailed an illicit love affair that left little to the imagination.

“I wish Kim was allowed to write more songs for the Pixies,” Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain told Melody Maker in 1992, having confessed to previously trying to rip the band off when he wrote Smells Like Teen Spirit, and included Surfer Rosa in his all-time top 50 albums. “Because Gigantic is the best Pixies song.”

A year later, the reluctant grunge stars would recruit Steve Albini for final album In Utero, in a bid to authentically capture the raw timbre of their new material (ultimately a cause of some controversy, leading to R.E.M. producer Scott Litt remixing two of the record’s singles). PJ Harvey, too, sought his sonic assistance for her own release that year, Rid Of Me. Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan was also a paid-up member of the fanclub, admitting that his band used to study Surfer Rosa, claiming, “it made me go, ‘Holy shit!’ It was so fresh. It rocked without being lame”.

Speaking in the Pixies documentary Gouge, a year before covering Cactus on his 2002 album Heathen, no less than multi-generational musical pioneer David Bowie singled the Bostonians out for special praise. “I found [Pixies] just about the most compelling music outside of Sonic Youth in the entire 1980s,” he remarked. “I always thought there was a psychotic Beatles in them.”

“It sounds like four kids doing the best they can,” Santiago modestly summarised. “There’s no bullshit or gimmicks on it.”

As it spent 60 weeks on the indie album chart, Deal remembers feeling “pissed off” at UK audiences for applauding before anyone had even played a note. European support shows with labelmates Throwing Muses eventually became bill-flipping headline affairs. Despite success away from home, the band remained virtual unknowns in the US.

Meanwhile, the bassist wanted more creative input and their chief songwriter didn’t want to give it up. During a short break in 1989, she duly formed The Breeders. A few albums later and the Pixies were opening for U2 on the American leg of their mammoth Zoo TV tour, but relations were frayed. On January 13, 1993, Francis announced their surprise split on BBC radio, confirming it via fax to the band later that day.

That summer, The Breeders had a big hit with Cannonball. Lovering turned down the chance to join Foo Fighters, eventually becoming a magician. Black Francis became Frank Black and released a series of records, both solo and with his new band, The Catholics. Santiago played guitar on a number of them, while also exploring music with his own band, The Martinis.

In the Pixies’ absence, a legend mushroomed as their impact became more pronounced. When David Fincher’s cinematic masterpiece Fight Club drew to a stirring conclusion while Where Is My Mind? played over the top in 1999, new audiences were introduced to the band on a global scale. In the years since, covers by Nada Surf, Placebo, Kings Of Leon, and even James Blunt have surfaced. It has been turned into a children’s book, and versions have helped sell everything from chocolate, to holidays, and headphones.

“It’s the song that pays my mortgage,” boasts Francis. “I get offers once a week for yet another advertisement, movie or TV show to use it. I say yes to all of them.”

On April 13, 2004, NASA used Where Is My Mind? to wake up the team working on the Mars Rover Spirit, following a successful software transplant. That same evening, the original Pixies line-up reunited at the Fine Line Music Café in Minneapolis, Minnesota. They’ve released new music in the years since. Kim Deal has even left and been replaced twice. But it’s never been quite the same.

It feels almost churlish to tell the Pixies’ tale within the context of how influential they were and remain. Even if they are credited as the primary influence on a band who defined a generation and changed the world. But such suggestions seem to rankle.

“Being original, influencing Nirvana so they could rip a song,” Santiago sarcastically replied when asked by Reuters what their contribution to rock music has been. “I’ll admit it, if Kurt Cobain ‘fessed up to it, fuck it, I’ll agree with it, you ripped us off.”

Thirty-five years on, Surfer Rosa still sounds so alive and ahead of its time, deserving of a legacy far greater than a footnote, or the suggestion of success by association. It’s a towering record in its own right, capturing a band almost too weird for comprehension, timelessly and lovingly rendered.

Formerly the Senior Editor of Rock Sound magazine and Senior Associate Editor at Kerrang!, Northern Ireland-born David McLaughlin is an award-winning writer and journalist with almost two decades of print and digital experience across regional and national media.