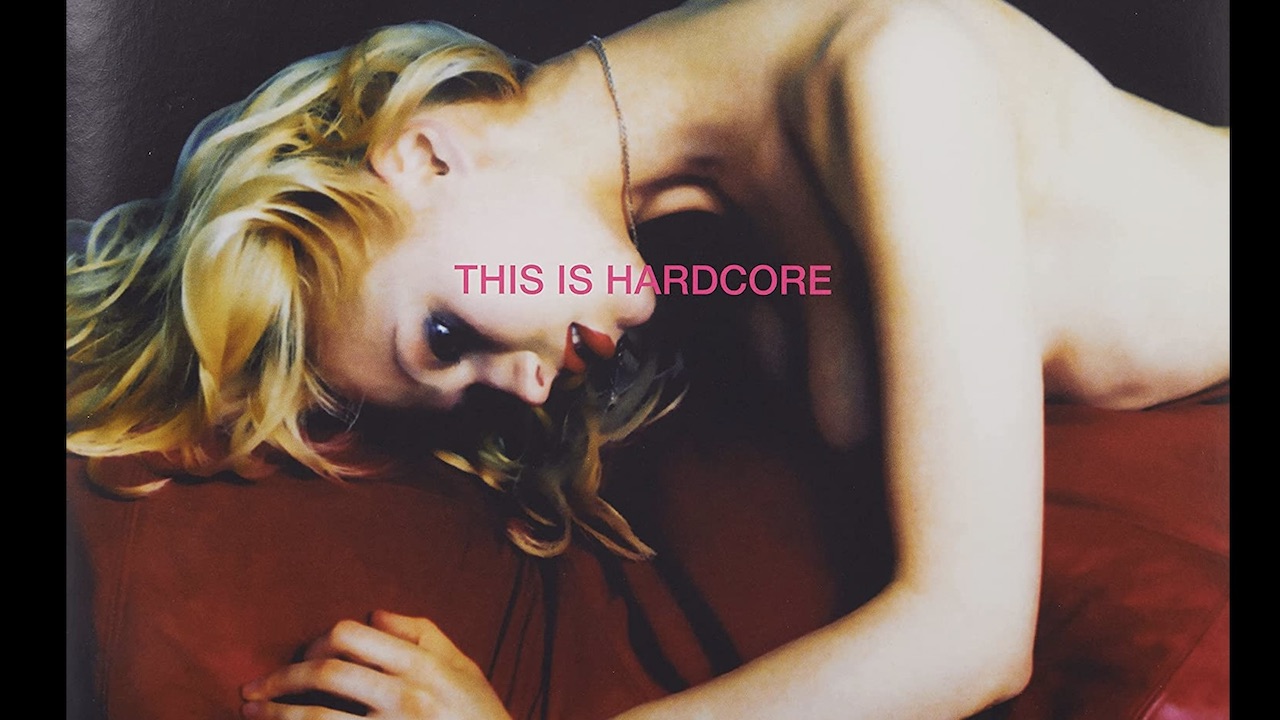

This is Hardcore: these dark depictions of the damaging, corrosive effects of fame illustrate why Pulp bailed on Britpop

A re-examination of Pulp's superb This Is Hardcore album as it turns 25

It remains one of music's great ironies that Pulp spent the best part of two decades trying to become a massive, crossover, guitar pop band, and when that finally happened, they realised they hated it and almost immediately did their very best to retreat.

In 1998 they released an album of sombre, baroque pop with no obvious singles which disappeared from sales charts worldwide almost as soon as it entered them. Yet, seen as a failure by many at the time, 25 years on, This Is Hardcore may actually be Pulp's most respected record.

Formed in 1978 in Sheffield by a teenage Jarvis Cocker, but really finding their identity in the early to mid 80’s when keyboardist Candida Doyle, guitarist Russell Senior, drummer Nick Banks and bassist Steve Mackey were added to the lineup, Pulp spent the majority of their first decade in existence as an underground indie pop band with a small cult following.

By the time the 90’s rolled around, no one really could have expected much more than the meagre chart placings and occasional Mercury Prize or NME Award nomination that the band were achieving. The quality of 1994’s His ‘n’ Hers, with magnificent singles Babies and Do You Remember the First Time, was sky-high and yet Pulp remained nearly men (and woman).

Then Common People happened.

Arguably the definitive song of the Britpop era, the first single from Different Class propelled Pulp's fifth album to the top of the nation's album chart, and then far north of one million sales in the UK alone. It transformed Pulp into an inescapable part of British pop culture, turning them into Glastonbury headliners and the pop stars they had always seemingly wished to be.

As is so often the case, this success came at a price. Jarvis Cocker went from 'indie darling' to 'national treasure' to 'tabloid target' with indecent haste, particularly in the aftermath of his infamous invasion of Michael Jackson’s performance at the BRIT Awards in 1996. Now his every move was scrutinised, and he was judged less for his music, lyrics and performances, and more on his style and the wittiness of the quips he’d deliver on TFI Friday.

After this whirlwind period, Pulp were exhausted, frustrated, struggling with media attention, substance abuse and each other. “You dream about what being a pop star will be like,” Cocker told Time Out in 1998. “and, like most things, when you get it, it isn't how you imagined." In the eye of the storm Senior quit the band, believing it “wasn’t creatively satisfying to be in Pulp anymore.” At their peak, the Yorkshire band excused themselves from the Britpop party.

Good job too, as, in their absence, it all turned sour. In 1997 Radiohead released their groundbreaking OK Computer album, a record of dense, dark, complex and emotionally fragile material that completely captured the public imagination, as did The Verve’s similarly downbeat, self-reflective Urban Hymns. Contrast the reaction to those landmark releases alongside undisputed Brit-pop kings Oasis’ third album Be Here Now, also released that year, which was derided for its bloated, cocaine-fuelled excesses. The cheeky chap, aspirational, good time vibes that defined Britpop had been usurped by feelings of deep melancholy. How were a band that only a few years previously were telling us all how to get Sorted for E’s & Whizz going to fit into this new landscape?

Rather well as it happens. Cocker began to craft new material whilst the fall of the Britpop empire was happening, taking well over a year to piece together the follow up to Different Class in isolation from the rest of his band, and away from the glare of the British press, in New York. Much of the crux of the album would come from his hang ups and neuroses about the success Pulp had achieved.

"Maybe I was too acquiescent," Cocker reflected to Time Out when asked about his period as a tabloid mainstay. "I just did everything that I was asked to do. This has been a fundamental change in my views. I used to be very hung up that I was from a sector of people who had been marginalised. ‘What, indie singers? No, no. Dole-y scumbags. The victims of Maggie Thatcher's ‘There is no such thing as society’ thing.’ So, I felt that if there was an opportunity to infiltrate the mainstream, I should take it and go and do all this press."

"What I've realised is that the mainstream has an emasculating or castrating effect. You invent this thing, this shield with which you protect yourself against the world, and you lose control of it. Suddenly the tabloids, whose moral values I don't subscribe to, have an opinion on what you do."

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Cocker felt as if he had lost control, and, struggling to once again find his voice, the creation of the new album became an arduous task.

"I wanted to carry on for the right reasons," he continued to TimeOut. “if you carry on because it pays the mortgage, or because you wanna be in magazines, then it's wrong. It did cross me mind that we'd done all we were capable of. I don't like being self-analytical, but I had to examine my motives.”

Such was the levels of exhaustion in the band, that the new album’s debut single, the arch chamber pop of Help the Aged, was the only completed song the band had for some time. Released as a single on November 11, 1997, reaching number 8 on the UK singles chart, it was well received by critics, but proved something of a shock to folk expecting another Disco 2000 and getting a song with Cocker confronting his own mortality.

"People said Help The Aged slunk out like a wet fart," sighed Cocker. "I thought, maybe naively, that the best thing to do was release something and let people make their own minds up about it."

With the creative process a painful one, relationships within the band fraught, and the themes of the album far more dour and resigned than previous material, This is Hardcore slowly but surely began to take shape as Pulp recorded at The Townhouse and Olympic studios in London with producer Chris Thomas. Cocker described the album as being about “Me trying to find a reason to carry on.”.

Released into a post-Britpop world on March 30, 1998, it topped the UK album charts after selling 50,000 copies in its first week on sale, this some way down on the 133,000+ Different Class sold upon release. In critical terms, Pulp’s willingness to explore new territories was lauded, but very few appeared to truly embrace it. “That which doesn’t kill you, makes you stranger.” shrugged the NME in their 7/10 review. It wasn’t long before the album was being referred to as a flop. The mainstream, it appeared, had rejected Pulp.

But, more accurately, this was a mutual decision. Pulp had decided to reject their own pop star status, and they vanished again for a few years fairly immediately after the album was released. Following an arena tour of the UK at the end of 1998 they only played another seven shows in the next two years, before briefly popping their heads up to release 2001’s We Love Life and splitting in late 2002.

In the years that have passed, the legacy and appreciation of This is Hardcore has grown massively. As we celebrate a quarter of a century since its release, we’re not the only outlet that would proclaim it as the finest record of Pulp’s career. Its cinematic, swooping, wry, seductive and hushed explorations on the price of fame, the seedy underbelly of mainstream success and the regretful damage it can do to your psyche is just so fantastically and consistently realised here.

From the moment Cocker wails "The end is near again" during the chorus of the warped Broadway stylings of opening song The Fear, it’s clear This is Hardcore is going to be something very different. Neneh Cherry turning up to add a Medusa-like performance, filled with slink and menace, on the 8-minute plus Seductive Barry is a masterstroke, the 'Bowie does death disco' of Party Hard is the grittiest Pulp have ever sounded and Sylvia is a borderline power ballad made by people who rejected Whitesnake for Scott Walker.

Best of all though is the title-track, perhaps the very best song of Pulp’s entire career. A six and a half minute long epic, it has the huge drums, marching horns, delicate keys and sweeping strings of a Bond theme, albeit one comparing the life of a porn star to being the famous singer in a successful pop band. It’s a genuinely magnificent song, and really should have been as definitive a song in the band’s back catalogue as Common People or Disco 2000, instead, much like Blur’s The Universal, it was underappreciated at the time, only reaching number 12 on the UK singles chart.

"That really broke my heart," said Cocker. "Because I'm really proud of that song. It was a shame it didn't do better. I suppose times are different.” Only now is it seen for the masterpiece it is.

Which is also true of the album on which it is the centrepiece. Revisited, or discovered by fresh ears that are not muddied by the context and expectation of the time, it regularly appears now in 'Best of' lists, with everyone from Pitchfork to Metro Weekly proclaiming it as something of a lost classic. Twenty-five years after it ostracised its creators from the mainstream, This is Hardcore has finally, and deservedly, found an audience that can appreciate it.

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.