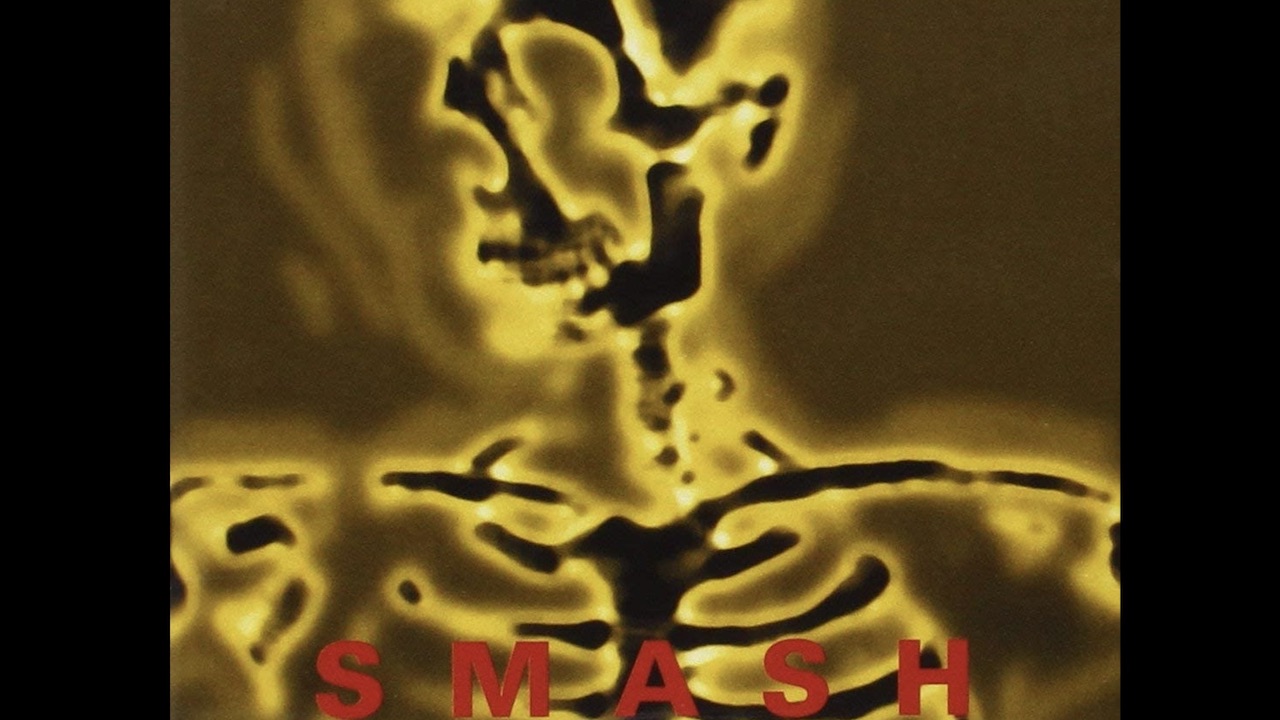

The story behind The Offspring's Smash: How a school janitor, a college nerd, a $5000 video and 11 million album sales turned the music industry upside down

Released on April 8, 1994, The Offspring's third studio album is the biggest-selling rock album ever released by an indie label. Here's how Dexter Holland, Noodles and co. Smash-ed it

There are so many notable stories married to the making and release of Smash that their impact can sometimes overwhelm. For one thing, the third album from Orange County punk quartet The Offspring, which celebrates its 29th birthday today (April 8) became, for a time, the highest-selling independent LP of all time. Despite latterly surrendering this title to Adele, it remains the world’s most popular indie rock album.

Even before its 14 tracks blew apart the boundaries that divided specialist record companies from their major label counterparts, keen senses were able to detect vibrations from tectonic plates that were beginning to shift. Never mind that the album’s modest recording budget of somewhere between twenty and thirty thousand dollars – in the 21st Century, memories are vague on the precise figure – required its producer, Thom Wilson, to live in a camper van while the band tracked its songs, upon hearing the finished result Brett Gurewitz, the owner of Epitaph Records, said to his wife of the time, “Everything’s changed. We’re going to be rich.”

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Because prior to the success enjoyed by Smash, and by its kissing cousin Dookie by Green Day, the prospects for independent punk rock acts – which is to say groups who identified as punk rock, rather than the upwardly-mobile punk-adjacent class of Nirvana and Pearl Jam – were limited indeed. When The Offspring toured the US with Pennywise at the start of 1994, that group’s singer, Jim Lindberg, remarked to his bandmate, guitarist Fletcher Dragge that he believed that their special guests might just break out given the quality of their new LP that had just been played to him by the group’s singer Dexter Holland. Snorting in derision, Dragge replied with words to the effect of, “Let ‘em get back to us when they’ve sold a 100,000 albums”.

One hundred thousand albums. That was the ceiling for a budding Californian punk rock group who hadn’t yet signed, or who didn’t wish to sign, with a major label. It’s nice work for those who can get it; it’s a decent living. But in hiring a professional plugger to shop the song Come Out And Play to radio stations up and across the United States, Brett Gurewitz at once declared his intention of raising the stakes. When the influential Los Angeles broadcaster K-ROQ began playing the song on increasingly heavy rotation, just like that, the game was on.

Strange, then, that at this pivotal point in their career The Offspring were little more than a part-time band. Guitarist Kevin “Noodles” Wasserman was employed as a janitor at the Earl Warren Middle School in the shadow of Disneyland, while bassist Greg K. worked in a print shop.

But it was Dexter Holland’s experience as a student at the University of Southern California [USC] that would prove pivotal in shattering the glass ceiling quarantining American punk rock from the mainstream. After seeing the dilapidated and violence-strewn streets of southern Los Angeles each day while driving in his beat-up car to the college campus, the then 28-year old composed a svelte and perceptive vignette about the gang warfare that had been scarring this most overlooked sector of the city for years. With the song about to be heard on radios from Berkeley to Boston, its authors spent $5000 filming a video in a friend’s garage. Never mind that the majority of the budget was spent on meat and beer for the barbeque at the end of the shoot, as fast as that the little band that suddenly could were on MTV.

More than any other major album released in the hectic 1990s – and with sales in excess of eight million copies, this was a major album indeed – Smash was content to let its music do the talking. Remarkably, during its initial blockbusting run at the box office, The Offspring consented to just one interview with the American music press (a cover feature with Spin magazine, a decision they promptly regretted). The group turned down offers to appear on Late Night With David Letterman and Saturday Night Live. When they did at last deign to appear on television for a live performance of the barnstorming Bad Habit, at the American Music Awards, Smash itself had been on the shelves for almost nine months. For good measure, that night Dexter Holland wore a t-shirt emblazoned with the words ‘Corporate Rock Kills Bands Dead’.

Because in those dangerous days of America’s multi-platinum Alternative Nation, it really did. As the singer would subsequently explain, “There was all this stuff where people [in bands] were literally dying because of what was going on, and so we thought, ‘You know, maybe it’s not a good idea to turn to heat up to a million and a half and hog the entire spotlight. Maybe it’s not a good idea, mentally, to do that.” He would later put it more succinctly still. “The music industry produces casualties,” he said. “That is for sure.”

But not of this band it didn’t. As the small staff at Epitaph Records worked day and night to keep Smash in the shops, millions upon millions of satisfied customers were at liberty to savour the joyous thrust of tracks such as Nitro (Youth Energy), Genocide and So Alone. Because even amid the wave of misfits and weirdos that had dominated the chart for much of ‘90s, the arrival of The Offspring offered something new. Never before had punk rock songs with such manic beats-per-minute been awarded platinum discs. And this was no flash in the pan, either. Such was the album’s continued resonance, in fact, that its second stand-alone single, the resonant and superior Self Esteem, was released more than nine months after its first.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

By which point, everything had changed. In Hollywood, Brett Gurewitz turned down an offer from Sony of $50million for a 49% stake in Epitaph Records. In an unhappy ending to the fairy-tale, the Offspring themselves would soon decamp for pastures new with a lavish recording contract with the Columbia label. By then, though, the band had made their point: that a punk rock act on a modest punk rock label could conquer the continents and seas on entirely their own terms. Satisfied with his lot, by the summer of 1994, Noodles even resigned from his job as a school janitor.

Barnsley-born author and writer Ian Winwood contributes to The Telegraph, The Times, Alternative Press and Times Radio, and has written for Kerrang!, NME, Mojo, Q and Revolver, among others. His favourite albums are Elvis Costello's King Of America and Motorhead's No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith. His favourite books are Thomas Pynchon's Vineland and Paul Auster's Mr Vertigo. His own latest book, Bodies: Life and Death in Music, is out now on Faber & Faber and is described as "genuinely eye-popping" by The Guardian, "electrifying" by Kerrang! and "an essential read" by Classic Rock. He lives in Camden Town.