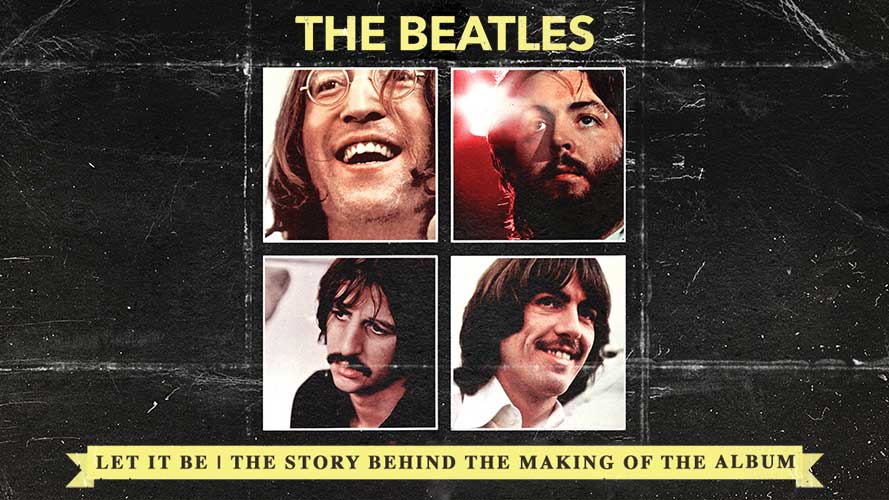

The real story of The Beatles' Let It Be sessions, told by those who were there

With the band falling apart, The Beatles set to work on a new album. More than 50 years after its release, this is the fractious story of Let It Be

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Let It Be might not rank high among all-time favourite Beatles albums, but the bizarre story of its making, riven with internal strife, drug-induced apathy, the public disintegration of what had been the world’s greatest pop/rock band, and a fistful of great songs makes it one of rock’s most fascinating artefacts.

The Beatles had been coming apart since the White Album sessions in 1968, but their warts-’n’-all documentary Let It Be and its soundtrack exposed the yawning chasms that had now consumed the formerly cuddly mop-tops.

Recalling the making of The Beatles/the White Album, Tony Bramwell, their roadie from the Liverpool days and later an Apple director, has stated: “Everything changed then. It became that Paul was doing lots and the others weren’t doing much more than being session men.”

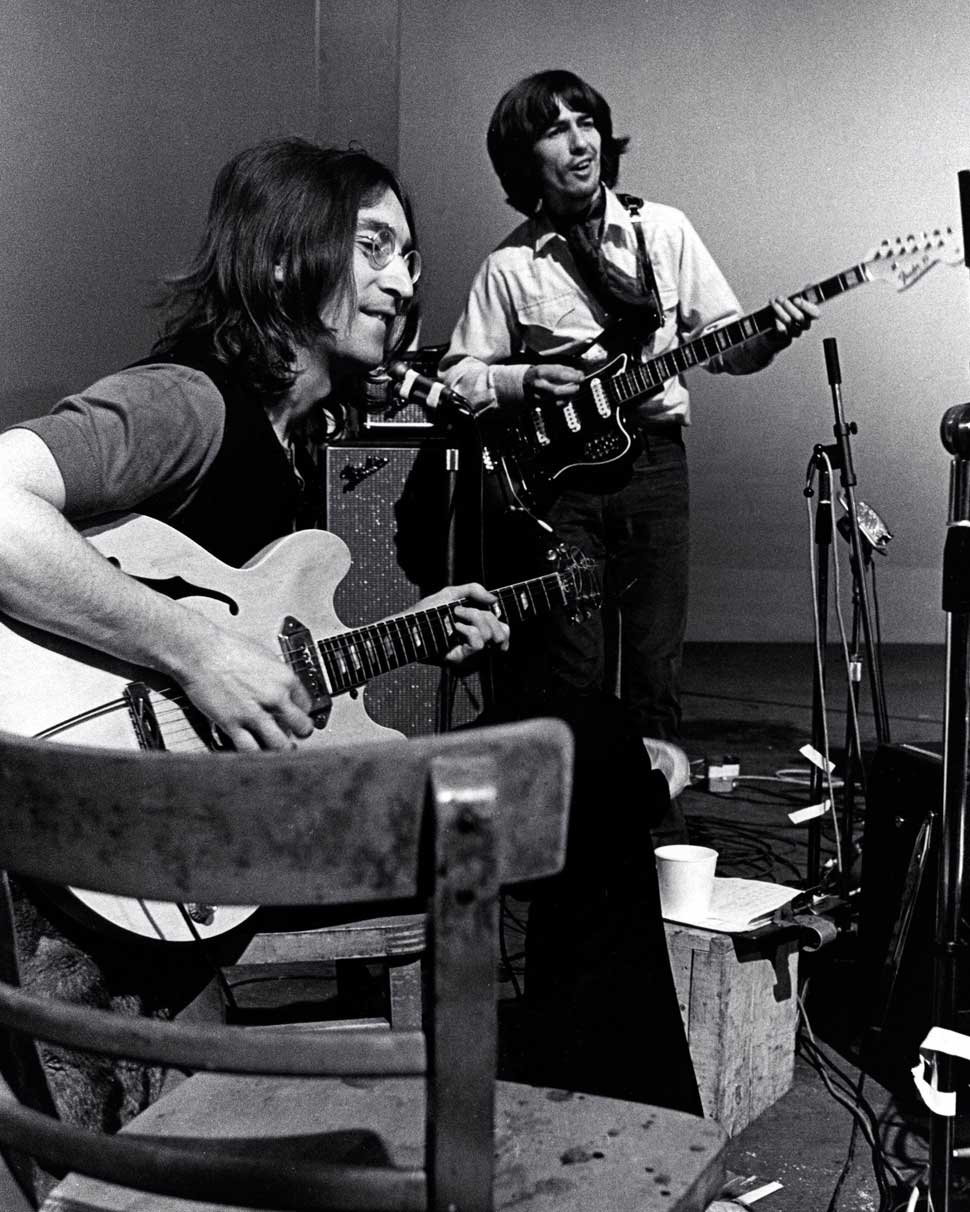

Article continues belowAccording to John Lennon, by the time Let It Be got under way in January 1969, “we got fed up being sidemen for Paul. And the camera work was set up to show Paul and not show anybody else. That’s how I felt about it.”

From George Harrison’s perspective: “I thought, okay, it’s a new year and a new approach. But it soon became apparent that it wasn’t anything new, it was just gonna be painful again. For me to come back into the winter of discontent with The Beatles… it was very unhealthy and unhappy.”

With the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, it seems glaringly obvious that they should never have even attempted to make Let It Be, but Paul McCartney’s supremely optimistic confidence carried them all forwards into a misadventure that proved not only unrelentingly miserable for all of them, but also just barely avoided destroying them forever.

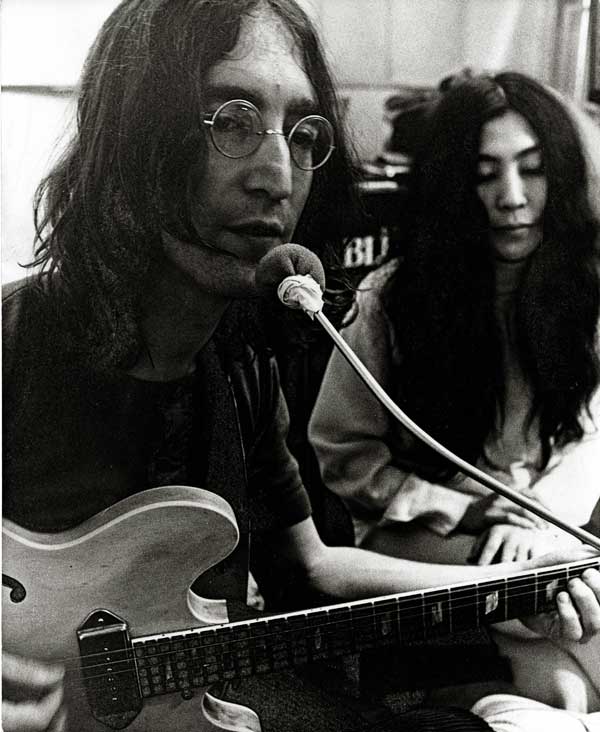

Complicating the already vexatious situation, Lennon’s heroin addiction was at its worst during the Let It Be sessions, and the others had no idea how to deal with it. As McCartney outlined to Barry Miles in his book Many Years From Now: “We were disappointed that he was getting into heroin because we didn’t really know how we could help him. We just hoped it wouldn’t go too far.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Despite the dice being so heavily weighted against them, as 1969 began The Beatles started recording sessions, and also filming with director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who had worked with them previously on promotional films for Paperback Writer, Hey Jude and other tracks.

Jan 2, 1969: At 10am The Beatles arrive at Twickenham Film Studios to begin rehearsals for a proposed TV show, Get Back. The project will eventually morph into the Let It Be album and film.

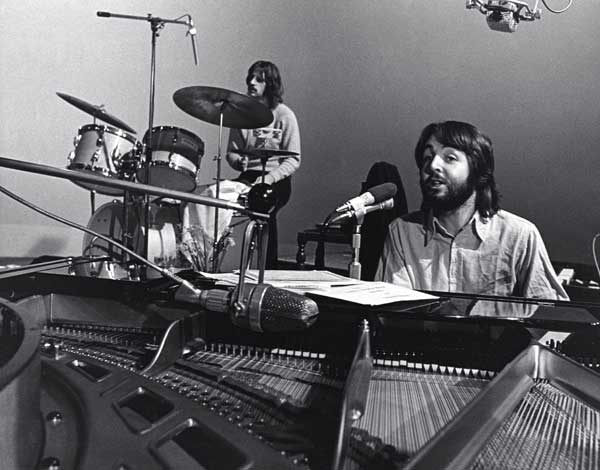

Paul McCartney: The idea was that you’d see The Beatles rehearsing, jamming, getting their act together, and then finally performing somewhere in a big, end-of-show concert.

Les Parrott (cameraman): My brief on the first day was to ‘shoot The Beatles’. The sound crew instructions were to roll/record from the moment the first Beatle appeared and to record sound all day until the last one left. We had two cameras and just about did the same thing.

Glyn Johns (engineer/producer): I was quite used to being around people who were famous. But when I got the call, to walk in and be privy to those guys sitting around, doing what they did, and to be invited in, was pretty astonishing. I didn’t know them. I was the same as every other punter on the planet, who saw them as these extraordinary icons of marvelousness.

[Producer] George Martin, being the gentleman that he is, realised that I had been compromised in a way, and he saw fit to put me at ease about the situation. He took me to lunch, and said: ‘You’re not to worry about a thing.’ I was feeling really awkward about the whole thing, and he was completely at ease about the situation. Because he is confident of his own abilities.

George Martin: Let It Be was the worst time of all, really disruptive.

Paul McCartney: What happened was, when we got in there, it showed how the break-up of a group works. We didn’t realise it but we were actually breaking up as it was happening.

Jan 3: Filming continues, but the proposed 10am start time has already been abandoned by Lennon and Harrison. Once they are all assembled, McCartney plays them Let It Be for the first time. The group works on One After 909 and Harrison’s All Things Must Pass.

George Harrison: It’s like hard work to do it. I don’t want to work, really. It’s a drag to get your guitar at eight in the morning, when you’re not ready for it.

Jan 4: Run throughs of One After 909, Don’t Let Me Down, Two of Us, I’ve Got A Feeling and Just Fun, the latter one of the first songs Lennon and McCartney ever wrote together, back in late 1957.

George Martin: We’d do take after take after take – and then John would be asking whether Take 67 was better than Take 39. I’d say: “John, I honestly don’t know.” “You’re no fucking good then, are you?” he’d say. That was the general atmosphere.

Jan 6: Working on Don’t Let Me Down and Two Of Us, with Lennon noticeably the worse for heroin.

George Martin: John became very druggy at that stage, and he knew how opposed I was to that. He ignored the others as well. On Let It Be I wasn’t allowed to make the record that I wanted to, because John said they didn’t want any ‘producer crap’. He said it was going to be an honest record for a change.

He said: “We’re not going to have any overdubbing, no editing, no messing about with tape cuttings. We’re going to go in there and perform like a band, and you’ll record it.” I said: “Okay, fine.” We started and, of course, we never got anything really right.

John Lennon: As usual, George and I were going: oh, we don’t want to do it, fuck, and all that. He [Paul] set it up, and there was all discussions about where to go and all that. I would just tag along. I had Yoko by then. I didn’t give a shit about anything. I was stoned all the time, too, on H etcetera.

Jan 7: After arguing all day in Twickenham about the Let It Be project, George Harrison writes I Me Mine, about the selfishness he feels is festering in the band.

John Lennon: We couldn’t play the game any more. We couldn’t do it any more. It came to the point where it was no longer creating magic. And the camera, being in the room with us, sort of made us aware that it was a phony situation.

Jan 9: Rehearsals continue at Twickenham. During this day Harrison plays I Threw It All Away, a Bob Dylan song that had not yet been recorded by Dylan. The group jam on a piece titled Suzy’s Parlour; McCartney introduces Her Majesty and Another Day; Harrison offers For You Blue.

Jan 10: Harrison walks out after arguments with both Paul and John. Lennon then suggests replacing him with Eric Clapton. Yoko Ono steps into Harrison’s position and begins wailing into his microphone. The other three accompany her with cacophonous feedback and thunderous drumming.

Paul McCartney (Let It Be soundtrack): I’m trying to help, y’know. But I always hear myself annoying you. It’s like we said the other day, I’m not trying to ‘get’ you. I’m saying: “Look, lads, shall we try it like this?”

George Harrison (Let It Be soundtrack): Well I don’t mind. I’ll play whatever you want me to play, or I won’t play at all if you don’t want me to play. Whatever it is that’ll be easier, I’ll do it.

George Martin: That [Yoko’s involvement] was a bit difficult to deal with. Suddenly she would appear in the control room. Nobody would say anything to me. I wasn’t even introduced to her, she would just sit there. And her influence would be felt.

George Harrison: I thought: “I’m quite capable of being happy on my own, and if I’m not able to be happy in this situation I’m getting out of here.” So I got my guitar and went home.

Eric Clapton: Lennon would use my name every now and then for clout, as if I was the fastest gun. I don’t think I could have been brought into the thing, because I was too much a mate of George’s.

Jan 12: The group convene at Ringo’s house, Brookfield, in Surrey, in an attempt to sort out their differences, but nothing is resolved.

Paul: It was like, no, no, no. Wait a minute, wait a minute. George has left and, you know, we can’t have this, this isn’t good enough! So I’m not sure what happened. I think maybe Neil or one of the ones who looked after us probably rung George up and said: “They’re real sorry,” or whatever, “it was a real big mistake.”

Jan 13: Paul, Ringo and, eventually, John turn up at Twickenham but no work is done.

John Lennon: We couldn’t get into it. It was a dreadful, dreadful feeling in Twickenham Studio, and being filmed all the time. I just wanted them to go away. And we’d be there, eight in the morning. You couldn’t make music at eight in the morning or ten or whenever it was, in a strange place with people filming you, and coloured lights.

Jan 15: Harrison returns to the group, agrees to be filmed making an album, but suggests they use the 72-track state-of-the-art studio being built for them by their friend, the Greek artist/inventor ‘Magic’ Alex Mardas at Apple’s Savile Row HQ.

George Harrison: It was decided that it would be better if we just got back together and finished the record. Also, you see, Twickenham studio was very cold and not a very nice atmosphere, so we decided to abandon that and go to Savile Row, into the recording studio.

Tony Bramwell: Magic Alex Mardas, a Greek bloke, had somehow convinced The Beatles that he could invent all sorts of wonderful electronic gadgets, so they set him up with his own company, Apple Electronics, and gave him the job of designing their studio.

George Martin: The trouble was that Alex was always coming to the studios to see what we were doing and to learn from it, while at the same time saying: “These people are so out of date.” But I found it very difficult to chuck him out, because the boys liked him so much. Since it was very obvious that I didn’t, a minor schism developed.

Jan 18: Lennon recklessly reveals to Disc And Music Echo editor Ray Coleman that “Apple is losing money every week… If it carries on like this, all of us will be broke in six months.” When the quote is printed it causes consternation throughout the entire Apple empire.

Tony Bramwell: There were huge expenses bills, catering, drinks, free cars and houses for people. Every Beatle had his own personal assistant, all of them overpaid.

John Lennon: Everybody connected with us is millionaires except for The Beatles. They used to tell Paul and I we were millionaires, and we never have been… George and Ringo are practically penniless.

George Harrison: Apple has plenty of money. We all have. When John said we were losing money, he was telling about giving too much away to the wrong people. We have given too much to charity, we’ve just been too generous and that’s going to stop.

Jan 20: Hoping to resume work on Let It Be, The Beatles turn up at the studio created by Magic Alex in the basement of the Apple HQ in Savile Row, but it is quickly found to be totally unusable. Mardas’s promised 72-track tape system had been reduced to 16 tracks, there was no soundproofing, no talkback and no wiring between the control room and the studio speakers. It will eventually be estimated that Mardas’s various projects had cost The Beatles at least £300,000 (more than £5m in today’s money).

Barry Miles (label manager, Apple Records subsidiary Zapple Records): ‘Magic’ Alex must have been a considerable drain on resources. I never had any faith in Alex. It was John and George who championed him. He was going to invent all these incredible things, like a door that could tell friend from foe, and would only let in people with good vibes.

Ringo Starr: Magic Alex invented electrical paint. You paint your living room, plug it in, and the walls light up! We saw small pieces of metal as samples, but then we realised you’d have to put steel sheets on your living room wall and paint them.

Tony Bramwell: John had such absolute faith in Magic Alex that he let him run up all kinds of massive bills, and none of it ever came to anything.

George Harrison: It was the biggest disaster of all time. He didn’t have a clue.

Jan 22: Harrison asks American keyboard player Billy Preston to play on the Let It Be sessions. The Beatles resume work at Savile Row, which has been speedily brought up to a tolerable standard by George Martin. They run through Dig A Pony, I’ve Got A Feeling, Don’t Let Me Down, She Came In Through The Bathroom Window (the latter will end up on Abbey Road) and several covers.

Billy Preston: I was on tour with Ray Charles and we were in London. George was at the concert and thought: “Hey, that looks like Billy Preston.” So he called around and found out that it was me. He called me at the hotel and invited me over to see the guys. Before I got there, Mal Evans had told me that they had been going through a lot of depression, and that he was glad that I came around because it gave them a lot of life.

It made them happy a little bit. When I got there, they were filming Let It Be and recording and all. We started reminiscing and playing old rock’n’roll songs. They said: “Sit in. You want to stay and help us finish the album? Take a solo…” They just made me a member of the band.

George Harrison: It’s interesting to see how people behave nicely when you bring a guest in, because they don’t really want everybody to know they’re so bitchy… Suddenly everybody’s on their best behaviour.

Jan 23: working on the McCartney composition Get Back, which had started life in the studio as an ad-libbed satire on Tory politician Enoch Powell’s speeches telling Commonwealth immigrants to “get back” home, but evolved into a straightforward nostalgic rock song.

Ringo Starr: We were working on a good track, and that always excited us. And his [Billy Preston’s] part was also a part of it, you know. Suddenly, when you were working on something good the bullshit went out the window, and we got back down to doin’ what we did really, really well.

Jan 24: The group work on Two Of Us, Maggie Mae, Dig It, Dig A Pony and I’ve Got A Feeling. They also record Teddy Boy, which will later be dropped.

Ken Mansfield (US manager, Apple Records): Billy was really special to the band at that time. I think George was very wise for bringing him in, because Billy was a calming effect. They were all really big fans of Billy. He was really important to the whole thing. When they were in the studio, they would play something and Billy would look over at me with his eyes just as big as saucers and go: “Wow, did you hear that?” And they’d turn to Billy and say: “Hey, why don’t you do this here?” and Billy would go: “Wow, that’s great.”

Jan 25: The Beatles complete Harrison’s For You Blue in six takes, and start work on McCartney’s Let It Be.

Jan 26: Work is done on Dig It and The Long And Winding Road, plus Harrison’s Isn’t It A Pity which will eventually appear on his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass. During the day it is also decided that they will record a live performance on the roof of the Apple building.

Jan 27: Work continues on Get Back, I’ve Got A Feeling and Oh! Darling. The latter will later appear on Abbey Road.

Jan 28: The Beatles record final versions of Get Back and Don’t Let Me down, as well as doing additional work on other tracks.

On the same day, Beatles publicist Derek Taylor gives Lennon’s phone number to controversial American music mogul Allen Klein, which leads to John and Yoko meeting Klein in the Harlequin suite of the Dorchester Hotel in London. They are very impressed, and John decides on the spot to make Klein his personal adviser. Shortly thereafter, Lennon writes his famous missive to Sir Joseph Lockwood, Chairman of EMI: “Dear Sir Joe: From now on Allen Klein handles all my stuff."

Allen Klein: I went straight to Lennon when he said they were going broke. Yup, outta the clear blue.

Peter Asher (Head of A&R, Apple Records): I had heard bad things about Klein’s dealings with the Stones, so I was rather alarmed when I heard John wanted to bring him in. He had allegedly done great things for a string of artists he’d had before, American singers like Bobby Darin or Bobby Vinton, but there was always a suspicion that he ended up with a bigger share of their earnings and futures than was proper.

Jan 29: Work continues on One After 909, Teddy Boy and I Want You. The latter is another track that will end up on Abbey Road.

Jan 30: The Beatles, with Billy Preston, perform a 42-minute set on the roof of the Apple building at 3 Savile Row. Having been mooted five days earlier by director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, because of resistance from George and Ringo it only secures final approval on the previous day.

Ringo Starr: There was a plan to play live somewhere. We were wondering where we could go – “Oh, the Palladium or the Sahara.” But we would have had to take all the stuff, so we decided “Let’s get up on the roof.”

Alan Parsons (tape operator): That was one of the greatest and most exciting days of my life. To see The Beatles playing together and getting an instant feedback from the people around them, five cameras on the roof, cameras across the road, in the road, it was just unbelievable.

Ken Mansfield: I’m four to six feet away from the band, so I’m virtually looking in their faces. When they started playing, at some point – and this is something I’ll never forget – there was this moment where Paul looked over at John or John looked at Paul and there was this look of recognition. It’s like they were saying: “You know what? No matter what’s going down, this is us. This is who we are. This is what we’ve always been. Stuff’s going down right now, but we are what we are, and that’s a good rock’n’roll band.”

George Harrison: We set up a camera in the Apple reception area, behind a window so nobody could see it, and we filmed people coming in. The police and everybody came in saying: “You can’t do that! You’ve got to stop."

Jan 31: The Beatles record a finished version of Two Of Us, bringing the sessions for the Let It Be album to an end.

George Harrison: Let It Be was supposed to be just a live recording, and we ended up doing it in the studio, and nobody was happy with it. But it was troubled times. Everybody listened to it back and didn’t really like it, and we didn’t really want to put it out.

During the spring of 1969, the Let It Be project moved into a protracted mixing phase, during which Glyn Johns tried on several occasions, without success, to deliver a mix that would satisfy The Beatles. By this point it was clear to everyone involved that the album was not going to be released in the immediate future.

In an attempt to get the band back on track, the irrepressible McCartney led them into the sessions that would produce Abbey Road. In the same period, McCartney married Linda Eastman in London, and a week later Lennon married Yoko in Gibraltar and then embarked on their Bed-in For Peace in the Hilton Hotel in Amsterdam.

Mar 10: Glyn Johns begins attempting to mix the Let It Be tapes into something The Beatles might approve. He fails.

John Lennon: The tape [Let It Be] ended up like the bootleg version. We let Glyn Johns remix it, we didn’t want to know. We just left it to him and said: ‘Here, do it.’ It’s the first time since the first album that we didn’t have anything to do with it. None of us could be bothered going in. Everybody was probably thinking: “Well, I’m not going to work on it.” Nobody could face looking at it.

Apr 11: After some last-minute remixing at Olympic Studios, Let It Be tracks Get Back/Don’t Let Me Down are released as a single.

Jerry Boys (tape operator, Olympic Studios): They’d already done a mono mix of Get Back and had acetates cut and didn’t like it… Paul and Glyn were very concerned with what the new mix was going to sound like on a cheap record player. Purely by chance, I happened to have a cheap record player in the back of my car, which I’d brought along to Olympic to have someone repair. We had an acetate cut from the new mix and then, using my record player, we were able to decide which of the two mixes was better.

Apr 18: John has by now convinced George and Ringo that Allen Klein could plug the holes in their business affairs. The three of them write to lawyer Lee Eastman (father of McCartney’s wife Linda), informing him that although he represents McCartney as an individual, they do not consider him their legal representative as a group.

Tony Bramwell: When Allen Klein came on board the whole atmosphere changed right away. You could no longer wander casually in and out of people’s offices. Doors were closed. He was very controlling about any of us having personal contact with The Beatles. Klein’s only interest was in being the manager of The Beatles. All recording projects other than The Beatles’ own things were stopped – even people like James Taylor who obviously had massive potential.

With Let It Be stuck in limbo, the remainder of the summer of 1969 was mostly given over to a variety of diverse projects. In May, Harrison released a new album, Electronic Sound, on Zapple Records. Klein was announced officially as the manager of Lennon, Harrison and Starkey. Even work on Abbey Road stopped, largely because the entire group had other commitments, including recording with other artists and holidays.

In September, Lennon announced that he was leaving The Beatles. On the business front, ATV failed in a bid to buy The Beatles’ publishing company Northern Songs. Let It Be didn’t start to re-emerge from limbo until the end of January 1970, when famed producer Phil Spector, who had been brought to the UK by Allen Klein, produced John Lennon’s single Instant Karma. Lennon was so impressed that he invited Spector to remix the Let It Be album tapes. The results would infuriate McCartney.

Mar 6, 1970: Let It Be, the version produced by George Martin, is released as a single.

John Lennon: That’s Paul. What can you say? Nothing to do with The Beatles. It could’ve been Wings. I don’t know what he’s thinking when he writes Let It Be.

Mar 23: In room 4 at Abbey Road studios, Phil Spector sets to work on the abandoned tapes for the Let It Be album.

George Harrison: Allen Klein brought in Phil Spector and said: “Well, what do you think about Phil looking at the record?” So at least John and I said: “Yeah, let’s see.” We liked Phil Spector, we loved all his records.

Glyn Johns: I was disappointed that Lennon got away with giving it to Spector, and even more disappointed with what Spector did to it. It has nothing to do with The Beatles at all. Let It Be is a bunch of garbage… he puked all over it… It was ridiculously, disgustingly syrupy.

Pete Brown (sound engineer, Abbey Road): He [Spector] wanted tape echo on everything. He had to take a different pill every half-hour, and had his bodyguard with him constantly. He was on the point of throwing a wobbly, saying: “I want to hear this, I want to hear that. I must have this, I must have that.”

Paul McCartney: We were getting a ‘re-producer’ instead of just a producer, and he added all sorts of stuff… backing that I perhaps wouldn’t have put on. I mean, I don’t think it made it the worst record ever, but the fact that now people were putting stuff on our records that certainly one of us didn’t know about was wrong.

Apr 2: Spector finishes remixing Let It Be.

John Lennon: He worked like a pig on it. He’d always wanted to work with The Beatles, and he was given the shittiest load of badly recorded shit – and with a lousy feeling to it – ever. And he made something out of it. It wasn’t fantastic, but I heard it, I didn’t puke. I was so relieved after six months of this black cloud hanging over, this was going to go out.

George Martin: To me it was tawdry. It was bringing The Beatles’ records down a peg. Making them sound like other people’s records.

Ringo Starr: I like what Phil did, actually. He put the music somewhere else and he was king of the ‘Wall Of Sound’. There’s no point bringing him in if you’re not going to like the way he does it, because that’s what he does.

The Spector version of Let It Be was released on May 8, 1970. It went to No.1 in the UK, USA, Canada, Australia, Holland and Norway, achieving platinum status in the UK and quadruple-platinum in the US.

Despite its indisputable commercial success, the debate continues to rage to this day, fuelled by several subsequent reissues featuring sundry remixes, about precisely where on the ladder of Beatles’ albums it should rank. Paul McCartney himself oversaw an alternate version Let It Be… Naked in 2003, but that’s another story…

Sources: The Let It Be film soundtrack; The Beatles Anthology; Magical Mystery Tours by Tony Bramwell; Matteo, Stephen (2004); Let It Be. 331/3 Series, Continuum International; Lennon Remembers by Jann Wenner, 1970; All We Are Saying by David Scheff; Many Years From Now by Barry Miles; The Beatles Bible website; A Hard Day’s Write by Steve Turner; Conversations With McCartney by Paul Du Noyer; Something Else Reviews; I Me Mine by George Harrison; Apple To The Core, McCabe and Schonfeld; Rolling Stone; The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn; interview with Larry Rohter in the New York Times, 2014.

Johnny is a music journalist, author and archivist of forty years experience. In the UK alone, he has written for Smash Hits, Q, Mojo, The Sunday Times, Radio Times, Classic Rock, HiFi News and more. His website Musicdayz is the world’s largest archive of fully searchable chronologically-organised rock music facts, often enhanced by features about those facts. He has interviewed three of the four Beatles, all of Abba and been nursed through a bad attack of food poisoning on a tour bus in South America by Robert Smith of The Cure.