"We’re still out there somewhere, on the dark side of the moon.” The progressive beauty of Mercury Rev

From acid-trip psychedelia to frayed, beautiful symphonies, we ask the question: how prog are Mercury Rev?

Mercury Rev have long been associated with music at its most freaky and far-out, ever since emerging from upstate New York in 1991 with a debut album of flipped-wig acid rock called Yerself Is Steam.

There was also the single Car Wash Hair, bearing sounds from the outer limits of psychedelic experimentation, notably on an untitled ‘hidden’ fourth track comprising 30 minutes of oscillating sine waves, looped thrash guitar, conversations with mental patients and blood-curdling screams. Their sounds were aided by long-standing producer Dave Fridmann. “My interest in Mercury Rev is down to Dave Fridmann’s great production methods,” says fan David Longdon of Big Big Train. “Their recordings are curious and highly creative.”

Much of Mercury Rev’s reputation for out-there artistry was due to the musicians’ frictional relationships, and the presence of totemic frontman David Baker and his believable impersonation of a lunatic asylum escapee. Following his departure after 1993’s second album Boces, guitarist Jonathan Donahue, he of the ravaged-choirboy vocals, assumed greater creative control, directing Mercury Rev towards a more beatific kind of music that imagined The Beach Boys’ Smile if Brian Wilson was as into distortion as he was divine melody.

The lack of commercial or critical response to third album See You On The Other Side (1995) and its lysergic doo-wop sent Mercury Rev into emotional freefall, and they – principally Donahue and guitarist/clarinettist Sean ‘Grasshopper’ Mackowiak – recorded 1998’s Deserter’s Songs in a void, assuming it would be their last. Certainly, Donahue’s heroin addiction and Grasshopper’s decampment to a Jesuit monastery in Spain suggested they were running out of road.

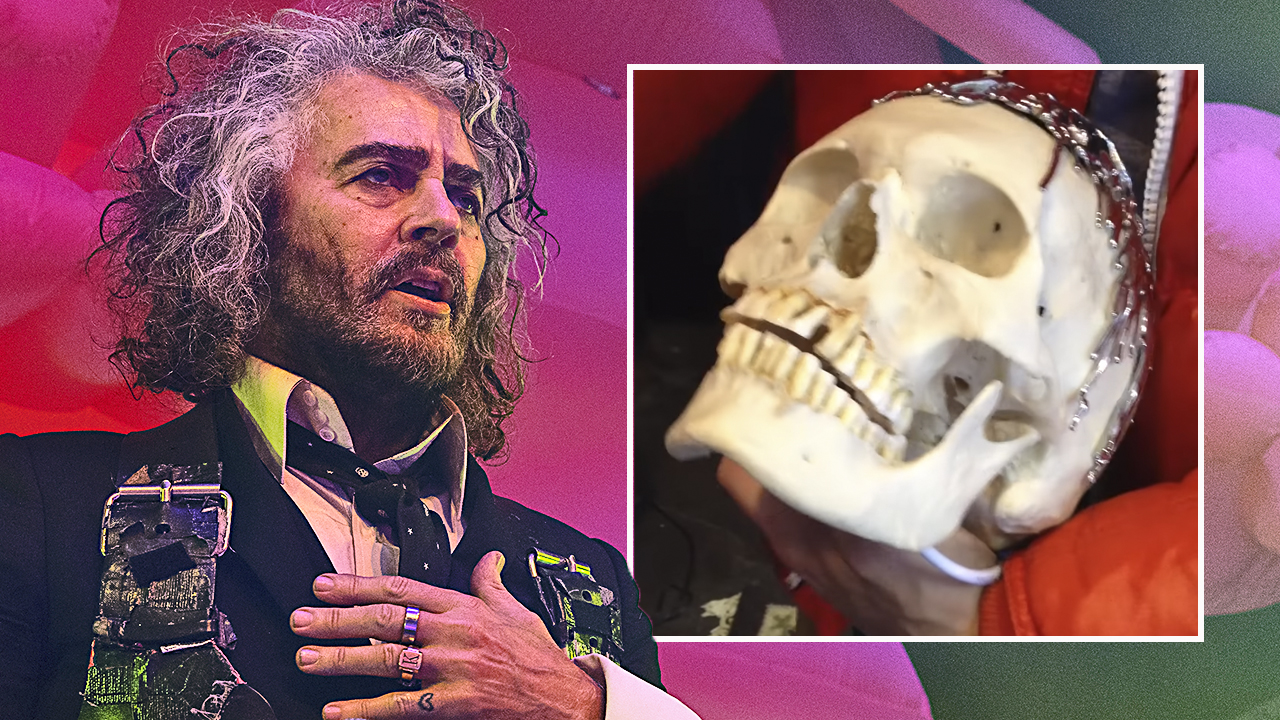

In fact, Deserter’s Songs won many album of the year polls and with its beguiling blend of space rock, roots rock and haunting fantasias, it established Mercury Rev, along with Flaming Lips (whose ranks Donahue joined in the late 80s/early 90s), as prime purveyors of cosmic Americana.

Since then, they have released three albums – 2001’s All Is Dream, 2005’s The Secret Migration, and 2008’s Snowflake Midnight – and all has seemed well in camp Rev. And with their fantastic(al) new album The Light In You, despite the seven-year gap, the Disney-ish sweet symphonies and sense of wonderment indicate high levels of personal happiness.

My interest in Mercury Rev is down to Dave Fridmann’s great production methods. Their recordings are curious and highly creative.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

But appearances are deceptive, according to Donahue. “We’re probably coming towards the light,” he says, alluding to their eighth studio album’s title, “because the last seven years have been so dark. Maybe that’s how everyone deals with it: you head towards something opposite. The Light In You was what pulled me out of the darkness of the past seven years. It has been very tumultuous, personally.

“In dark times, you do fall inwardly towards a place that is quiet and light,” he adds. “When everything around me is very chaotic or incredibly turbulent, maybe that’s where the heavy orchestral, fairytale, ‘Disney Jonathan’ comes from.”

You wonder whether Donahue’s voice is always this enervated croak suggestive of someone exhausted, even defeated. But certainly he makes no attempt to conceal the upheavals – his word – that he has endured between this album and the last, or indeed during the 25 years of Mercury Rev’s “accidental career”.

Donahue talks about the recent turbulent phase of his life in terms of space travel. “There’s the rocket ship’s trajectory – a very large emotional take-off – followed by the jettisoning of all the boosters and baggage and fuel along the way,” he explains. “And at some point you reach the upper atmosphere and all that’s left is you and the capsule and it gets very quiet.”

You would never know that the album was written in a depressed state. If anything, The Light In You amps up the ‘pretty’.

“We fell in love once again with the orchestral side of us,” says Donahue. “The ‘pretty’, or the Disney aspect, has always been running through our veins, and on this album it came right to the surface of the skin.”

Donahue grew up “in the mountains” outside New York, without an older brother to get him hip to the latest trends. “I never got punk rock or even glam rock,” he shrugs. Instead, he was surrounded by kids’ Disney records, his mother’s Russian classical music and the outlaw country loved by his father. “There was no Beatles or Stones, no Chuck Berry or Sex Pistols, just those three things colliding.

“It sounds odd,” he continues, “but I guess in a way my whole musical writing career has been to recreate those childhood moments, all these strange fantasias with a narrating storyline on top.”

In the early days, Mercury Rev were seen as acid crazies, but in reality the members were serious film students at the University At Buffalo, encouraged to explore their musical talents by their mentor, minimalist composer and multimedia artist Tony Conrad.

“I do have that Disney-esque, romantic, childlike side,” concedes Donahue, “but there is also the part of me that studied with [poet] Robert Creeley and took classes with Tony Conrad and was close to some of the very avant-garde American composers at the time, as were David Baker and Grasshopper, both of whom studied with a lot of avant-garde filmmakers at college.”

Despite being contemporaries of the grunge bands, Mercury Rev were seen more as latter-day exponents of psychedelia – Donahue remembers several comparisons with Hawkwind. Actually, he was unfamiliar with late-60s psych and early-70s space rock. “It was only later that I’d hear those records and be, like, ‘Oh my gosh.’”

Nor were Yerself Is Steam or Boces made, as some suspected, in a state of acid delirium. What threw Mercury Rev into turmoil wasn’t narcotics but too much acclaim too soon. Within a couple of months of their first feverish write-ups in the UK press, the band – who began as a sort of one-off cassette project with no intention of it lasting – were invited to perform at the 1991 Reading Festival. “That’s what shattered us,” reflects Donahue.

The subsequent recording of Boces was, he says, “a really tough time”. Suddenly they had to adjust to the idea of this as a ‘proper’ band. “It just took off so quickly, people were caught unaware,” he admits. “It was like, now we were a real band doing real tours, and we were having to answer real questions about our relationships. It began to shake the whole foundation of what began as six friends.”

How fraught were the Boces sessions? “It was very emotional. It was six people, fragile and frayed at the edges. A lot of friendships began to disappear back into the mists.”

Mercury Rev kept things together sufficiently to record See You On The Other Side, which Donahue considered a breakthrough, and was the forerunner of Deserter’s Songs’ lush soundscapes.

“I’m glad you say that because I’ve been beating that bell for years and no one listens,” says Donahue. “People like to think Deserter’s Songs fell from the sky, but I’d been working towards that goal for years. I just thought, ‘Gosh, this is just what the world needs, this is beautiful.’”

Unfortunately, what the world decided it needed weren’t songs such as Everlasting Arm and A Kiss From An Old Flame (A Trip To The Moon), but Britpop’s jaunty retro-rock.

“Everyone just dived into Oasis and Blur,” he says. “See You On The Other Side came out in a vacuum – you could hear the tumbleweed. No one wanted to hear the beauty I felt some of those songs had. It was as if, for Mercury Rev, a candle was blown out. That was where the darkness began.”

Apparently, the See You…-era tours were so horrible, “you could write a book about them and you’d think it was made up or Hollywood had designed it. They were beyond even the clichés of break-ups and how dark and isolating it can be.”

We don’t know the rules, and if we do hear any, we’re very suspect of them. If we’re going to make mistakes, let them be ours, not someone else’s.

By the end of 1996, there was no longer a band. “Just two friends [Donahue and Grasshopper] who were no longer speaking to each other. Everything I’d known as an adult had just melted down.”

Donahue and Grasshopper became estranged and both, the former reveals, “dived into alcohol and substance abuse”. To stay afloat, Donahue worked manual labour jobs, but any money earned simply fed his cravings. “When you’re in the throes of that darkness and the self-destructiveness, you’re not thinking about writing or songs,” he admits. “The only thing you’re thinking about is more self-destructive behaviour.”

Then he hit rock bottom. “When you hit the bottom with heroin addiction, there’s no giant explosion or fireball,” he explains, via another outer-space metaphor. “It’s very much like landing on the moon: it’s very quiet. The only reason you know you’ve hit the bottom is there’s no one left around you, and all the apparatus that got you into orbit is just lying around you in pieces.”

What enabled Donahue to achieve re-entry, as it were, was an invitation from The Chemical Brothers to appear on their 1997 single The Private Psychedelic Reel. That encouraged him to rekindle his friendship with Grasshopper and start working once more, even if the results would, they presumed, be Mercury Rev’s last stand.

“We thought, ‘If no one’s listening, we might as well do it the way I hear it in my brain,’” says Donahue of the rationale behind Deserter’s Songs, an album that inspired a whole new type of questing American rock and paved the way for Flaming Lips’ similarly minded The Soft Bulletin.

As though to confirm the existence of a Rev curse, however, the follow-up, All Is Dream was released on 9⁄11. “I was living in the Catskills, one of the plane’s flight paths, and I remember waking up and watching it on TV,” he recalls. “It was only later Grasshopper called me and said, ‘Our record came out today.’ I hadn’t remembered. It was very painful on every single level.”

On The Secret Migration, Mercury Rev refined their sound, while Snowflake Midnight evinced a new electronic direction.

“We don’t know the rules, and if we do hear any, we’re very suspect of them,” he says. “I took that element from my time with the Flaming Lips. If we’re going to make mistakes, let them be ours, not someone else’s.” The conversation returns to the seven-year hiatus since the last album. What happened?

“So much personal upheaval,” Donahue says hesitantly, although he does mention 2011’s Hurricane Irene, which he says “wiped out the Catskills”, taking with it his studio and all the master tapes inside.

The music on The Light In You is lovely in spite of its traumatic provenance. Is its prettiness the natural corollary of his own unhappiness? “Maybe,” he says. “But if it is, I don’t know how much more I can take. How many dark periods in one person’s life can you fly through without hitting the side of a mountain?”

It has been a quarter-century of giddy highs and plummeting lows. And for Mercury Rev, that means sometimes they’ve shone brightly for all to see, and other times they’ve receded into the shadows.

“We’re like an astrological body that comes into view for a period of time, then disappears behind some other large heavenly body and people don’t know what happened to it,” he says. “People might not be able to see us, but we’re still out there somewhere, on the dark side of the moon.”

The Light In You is out on September 18 via Bella Union. See www.mercuryrev.com. for more information.

YOUR SHOUT

They certainly know a good harmony when they hear one. But are they prog?

“I’d say the earlier albums are very much psychedelic prog. Boces is brilliant.” Stephen Pieper

“Well, they are not Yes type prog but they certainly are progressive in that they always reinvented themselves instead of bashing on the same formula all the time. I will give them a prog pass.” Randall Haake

“About as prog as the Flaming Lips. More art rock than prog.” James McLarnon

“And a good shout! Distinctive vocals great sound but can’t really think of an epic prog track? The Dark Is Rising had the makings but overall too close to the Flaming Lips – and are they prog?” Richard Anning

“Yes they are 8⁄10 prog points from me.” Fabien Wiedenhofer

“I reckon there more art rock than prog. Having said that…”Daniel Black

“Unique art rock which I’d have to say is progressive.”Ed Webb

“All Is Dream. Oh yes. Most certainly. Not that it matters when it is that beautiful. And Saw Song must be one of the proggiest instruments ever… a pre-theremin theremin if you will.” Philip G. Lort

“No.” Brian Stanbrook

“They covered Solsbury Hill on their last UK tour – that’s gotta count for something.” David Miller

“Not unless you are re-branding the magazine as Prog incorporating Tripped Out Art Rock. Prog of hipster convenience at best.” Ian Blackaby

“ I LOVE Mercury Rev. I saw them supporting Bob Mould, fantastic! Them and Flaming Lips, far more progressive than the retro neo-prog stuff.” Matt Stevens

“The lines of prog have well and truly blurred for me over the years. To me, Nils Frahm’s Says is prog. I find The Cure ‘progressive’, Disintegration and Wish for sure… Mogwai the same. Minus the capes of course.” Stu Wright

“You can’t be serious.” Thomas Gitopoulos

“Prog: no. Progressive in a winder sense? Why not. The first time I heard Goddess On A Highway, I thought it sounded like Caravan.” Pedantic Pedestrian

“Who?” Mike Holt

“I heard Jerry Ewing play a track from the new album on the Prog Magazine Radio Show. It sounded like it fitted in perfectly with all the other music he was playing that night. So why not?” Jan Piper

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.