The Outer Limits: How prog are Dillinger Escape Plan?

Deep thinking, dangerous live shows and an unpredictable sound with a punk core – that sadly is now coming to an end. So we had to ask: how prog are The Dillinger Escape Plan?

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

I t’s the late 90s, and an intelligent, dark-haired young man walks into his corporate job in the United States. He’s smartly dressed in a suit and tie, but as he limps to his desk, past the water cooler, his colleagues notice that he has two black eyes, and his ankle is strapped up after taking a nasty strain the night before. It happens most Mondays, the result of an aggressive underground movement that pushes itself to the mental and physical limit every weekend in search of true freedom and meaning outside the daily grind. And it’s not Fight Club… it’s real.

This man is Ben Weinman, guitarist and founding member of The Dillinger Escape Plan, one of the most fearless and challenging bands of the 21st century. A mathcore band who take the atomic heart of hardcore punk and split it, before throwing into the resulting mushroom cloud bizarre glitches, samples, elements of jazz, pop, metal, poetic screams and music there’s not even a word for yet. It’s an apoplectic world of their own that takes them far from the norm.

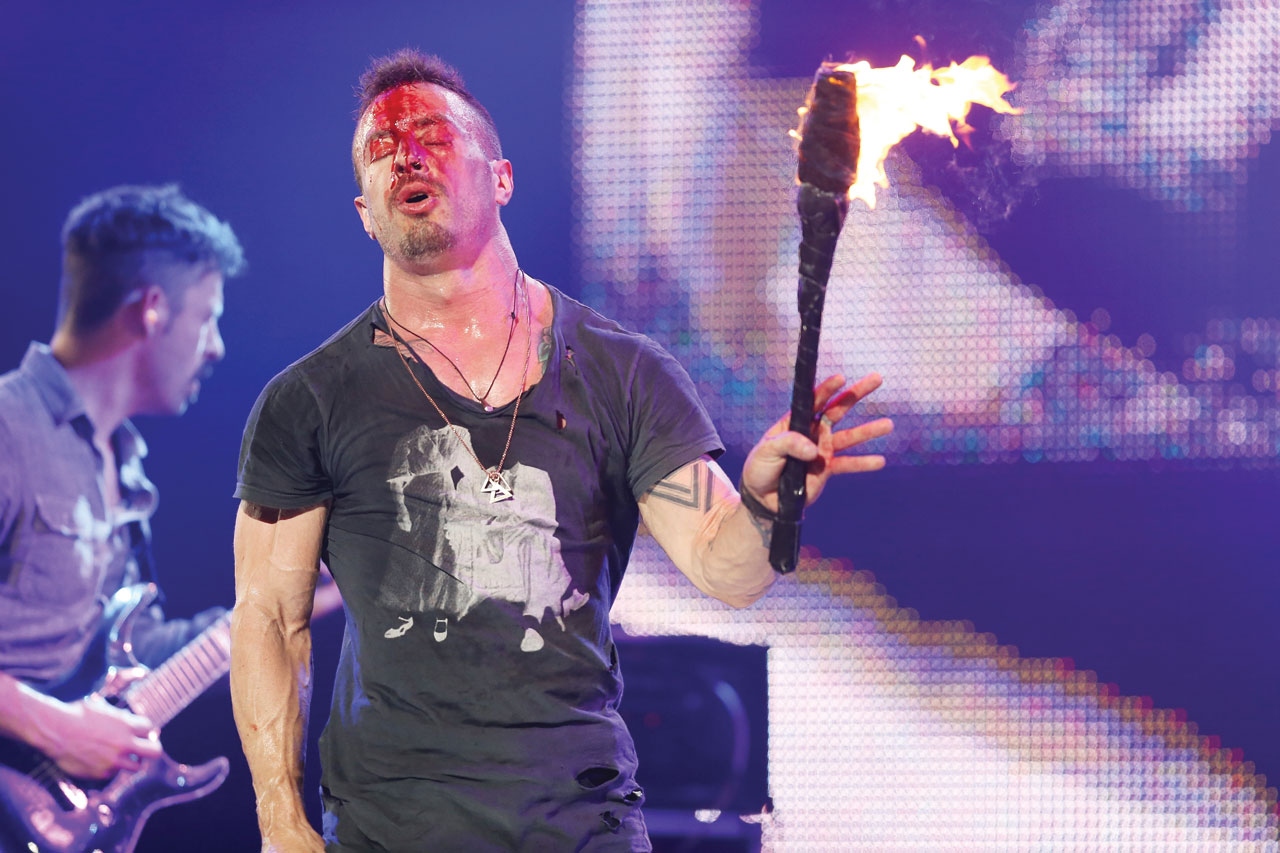

Live shows are famed for their unhinged sense of danger and unpredictability, muscle-bound frontman Greg Puciato frequently splitting his head open, spraying his blood across the stage, flinging his body from balconies, spitting fire, while Weinman wrestles his guitar in a spell of pure musical possession.

Article continues below

It’s a work of performance art. It’s therapy. It’s a primal scream. It’s like nothing else you’ve heard or seen before. And if that’s not progressive then what really is?

“All you really want to do when you’re creating art is to just have complete, uninhibited free expression,” says Weinman. “It was more about not thinking too much about what’s happening or the consequences or anything like that. Dillinger just embodied that from day one, and it just got crazier and crazier. I was working all week and going to school, saving every penny I had just to be in a band. Then I’d bash my guitar into a thousand pieces and then be like, ‘Shit, what am I going to do now?’ Or I’d be going to my corporate job with a black eye. People were like, ‘What the fuck is wrong with you?’

“We create music that’s challenging to us. And that demands our full attention, and demands that we lose ourselves in it. And that’s been the great thing about this band. You have to be just in the moment. And I think that’s what I’ll miss the most.”

Ah yes. This is the bad news. If you’re new to Dillinger, this is your last chance to experience the visceral thrill of their live shows. They’ve decided to mark their 20th anniversary as a band in 2017 by splitting up, after they’ve finished touring their latest (brilliant) album Dissociation. It’s a very Dillinger move to make, going out on a high when they’re still at the top of their game. After 20 years on the road, living and breathing TDEP 24 hours a day, to a claustrophobic and weirdly co-dependent extent, they’re closing this chapter and moving on to the next.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“We’re at a time where it makes sense artistically and individually, and in our personal lives,” says Puciato, who joined the band in 2001 after the departure of his predecessor, Dimitri Minakakis. “You wake up every day and this is the biggest thing in our lives. I think if we’re ever going to see what happens to us personally, without The Dillinger Escape Plan, now’s the time to do it, not when we’re 60 years old. And the other thing is just that we kinda went through a lot over the last few years, which means we’re drastically further along as people, psychologically, than we were three years ago. It felt like we hit some sort of resolve in our lives, and as far as what we have to say musically, where it just seemed to make sense.”

As that statement suggests, it hasn’t been an easy ride. The relationship between Puciato and Weinman is intense, and that tension has often been both the creative spark for the music and, during the difficult birth of 2013’s One Of Us Is The Killer, when they were living very different lives on opposite coasts of the US, the thing that threatened to rip them apart. “Greg and I were very, very strong-willed and very controlling,” admits Weinman.

“We were a lot more self-destructive three years ago,” says Puciato. “Since then we’ve gone through a lot of work to become more aware of those self-destructive tendencies that we ended up kind of abusing each other with over the years. We used Dillinger records kind of as therapy and as a way to skim the top off that thing that was causing you to have all this propulsive energy.

“I was in particular really, really reckless,” adds the frontman. “Ben was really reckless in a different way. And we kind of traumatised each other because of our recklessness. We got to a point where we had to deal with the things that were causing us to be that way, and I think we got through all that and have found a sort of calm now, some sort of peaceful resolution. It seems like a nice way to wrap things up. We’re getting along better than ever and I feel like we just made a really good record, so why not stop? If you think of things like a play or a movie, the first act is where you set the story, and in the second act there’s a problem that everyone has to overcome, and in the third act it’s resolved that problem. We’ve resolved almost everything. It’s not about money or about paying your bills, it’s making a complete artistic statement out of your band, instead of it being this ongoing soap opera.”

They’re very deep thinkers, something people may not realise if they take the violence of the music or the propulsive insanity of the live shows on superficial face value. This is a smart band making smart music. Weinman has a degree in psychology, and Puciato has a knack for self-analysis – his sessions in therapy, dealing with his anxiety, have helped him form the lyrics to the new record.

“When you go to therapy you just kind of dump all your shit out in front of you in a way that makes you look at it really literally,” he says. “That crept into my writing a lot because when you’re younger you’re just pissed and you don’t know why, and it kind of shrouds itself in metaphor and abstraction. And then the next record you kind of know a little bit more of what you’re dealing with… I won’t go into it because I feel like I’ve said what I wanted to say on the record. But if you know me, it’s very, very literal. It’s very honest, nearly shockingly. It was almost uncomfortable to write about.”

There’s an awful lot of brains that have gone into this none-more-brawny music. “We started at a time in the 90s when nu metal was the big thing: formulaic, predictable, based in heavy metal,” says Weinman. “And we did the opposite; we created music that was completely unpredictable, that was obnoxious, that was completely polarising, and from the very beginning people either completely loved us or hated us. And that was important for us, to push things in a way that was making people really have to think and take time and work. Because the music that ended up shaping our lives as young people was music like that. The music that really made a difference and influenced us was the music that was unique and taking risks.

“Even in the mainstream world there were bands like Soundgarden, prog music and punk music. There was the underground electronic music that was really progressive. Fusion music from the 70s started seeping its way into our playlists – we started really getting into things like Mahavishnu Orchestra and King Crimson. So that stuff was all super punk to us – especially in a climate where ‘punk music’ was like fucking Green Day – that was really pushing things and eclectic, and not easy to swallow. That was punk. This was stuff your parents may not get.”

But it’s one thing having this great masterplan and it’s quite another to translate it onto the stage, to strip away your layers until you become a wild animal, to lose all sense of self until all that’s left is the raw emotion that’s been clawing to get out from just underneath the surface.

“Tapping into it feels pretty natural to us at this point,” says Puciato. “We’ve made it such a part of how we cope with anxiety, how we cope with life, that I think one of the things about ending the band that’s going to be most difficult is: what are we going to do? We’ve used this band as a coping mechanism, and we’ve written this kind of music as a way to skim the froth off the top. Without the band, what are we going to do to counteract that, to make sure that stuff doesn’t bubble over into your real life? That remains to be seen, I suppose.”

“Over 20 years we’ve been doing this successfully on our own terms,” adds Weinman. “That’s the product, us just being honest. Honesty – that’s what we’re selling.”

They’re fearless. They’re unique. They’re their very own living work of art. This is prog, punk-style. Make the most of it before it’s gone.

Dissociation is out now on Party Smasher/Cooking Vinyl. For more information, see www.dillingerescapeplan.com.

The Dillinger Escape Plan in tour bus smash

How metal is Dillinger Escape Plan guitarist Ben Weinman?

Party Smasher: Greg Puciato's 15 Most Significant Dillinger Escape Plan Songs

Emma has been writing about music for 25 years, and is a regular contributor to Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog and Louder. During that time her words have also appeared in publications including Kerrang!, Melody Maker, Select, The Blues Magazine and many more. She is also a professional pedant and grammar nerd and has worked as a copy editor on everything from film titles through to high-end property magazines. In her spare time, when not at gigs, you’ll find her at her local stables hanging out with a bunch of extremely characterful horses.