"I'm physically lifted from the seat and violently spun around by a pissed-off John Paul Jones": Led Zeppelin - Out of Control in the USA

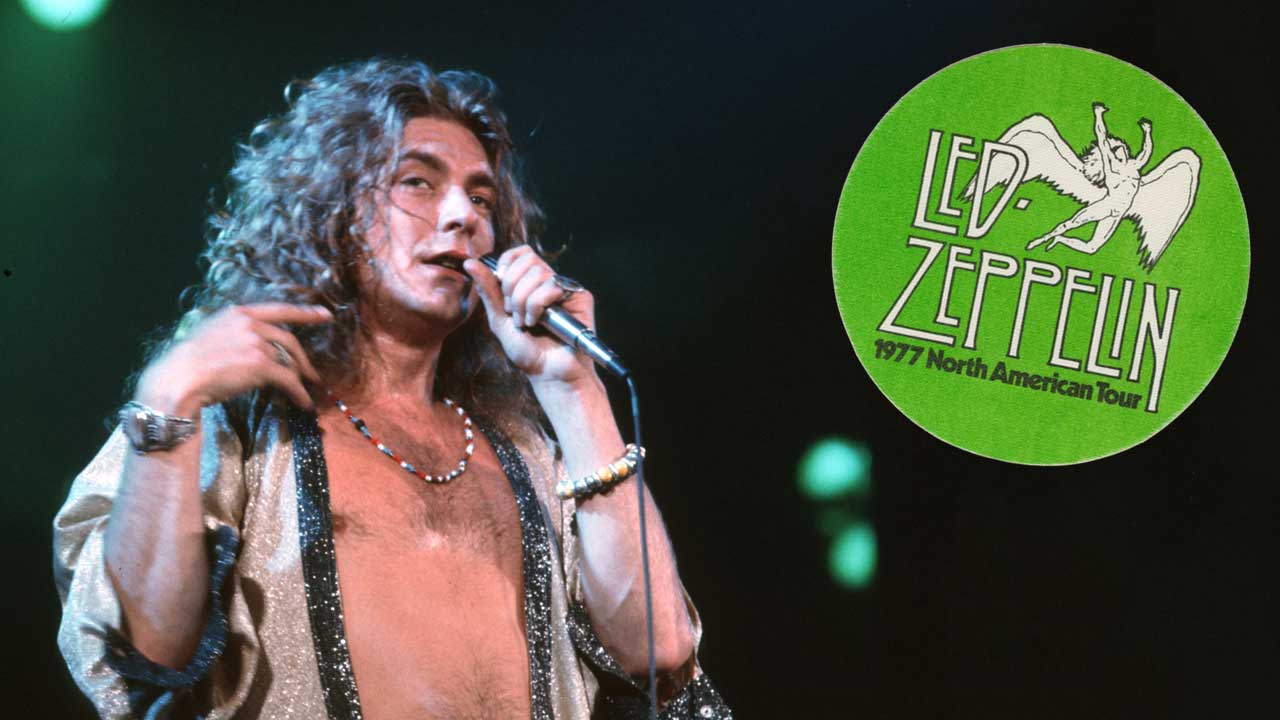

Led Zeppelin’s final tour of the US in 1977 should have been their most glorious. But it wasn’t. There was tension, unpleasantness and negativity, and that was just the start

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It's April 15, 1977. Tonight Led Zeppelin play the ninth date of the second leg of their eleventh American tour. I’m on board Caesar’s Chariot, the band’s customised Boeing 707 jet. Named after the conquering emperor who was ultimately doomed by an addiction to his own glory, this gleaming, luxuriously appointed flying fortress now carries an invading force of a different kind.

Just hours earlier, Zeppelin had annihilated a sell-out audience of pagan revellers at the St Louis Blues Arena. Now we’re returning to Chicago where, for the next several weeks, the band have set up their base of operations for the tour.

On the previous two tours, in 1973 and 1975, they adopted a similar strategy – positioning themselves in one location and then flying out to concerts. It’s the brainchild of tour manager Richard Cole, Zep manager Peter Grant’s first lieutenant and long-time ‘fixer’.

“It [Led Zeppelin’s 1977 tour] wasn’t a lot different to me from the ’75 tour,” Cole says. “It was the same process of working, you know. We had our 707 jet, and I worked out what cities were in range of Chicago. It was easier to leave at three or four in the afternoon, go to our plane and fly straight into the city we were performing in, leave straight afterwards and go back to Chicago.”

That’s where we’re headed now. I’ve been ensconced in Chicago’s Ambassador East Hotel for 11 days; a week-and-a-half of unchecked excess and dark rumblings. The former balanced the latter. The plane, for instance, has been refitted to include a bar, two bedrooms, a 30-foot couch, and a Hammond organ. Luxury comes at an uncomfortable price – the aircraft costs $2,500 per day to lease. Is it worth it? Who cares? Not Led Zeppelin.

Still, amid this luxury you can’t help but notice how drummer John Bonham lumbers about the cabin, a bottle of something in his hand, greeting everyone he encounters with barely concealed contempt. He walks past me, and I don’t dare make eye contact – it is one of the many instructions I’ve been given for my stay with Led Zeppelin.

On the day I arrived, a limo had been sent to the airport to collect me. Janine Safer, the group’s publicist, accompanied me as we rode to the hotel. Along the way she laid down five rules that had to be strictly adhered to while caught up in this travelling circus.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Rule 1: Never talk to anyone in the band unless they first talk to you. Rule 2: Do not talk to Peter Grant or Richard Cole – for any reason. Rule 3: Keep your cassette recorder turned off at all times unless conducting an interview. Rule 4: Never ask questions about anything other than music. Rule 5: Most importantly, understand this – the band will read what is written about them. The band do not like the press.

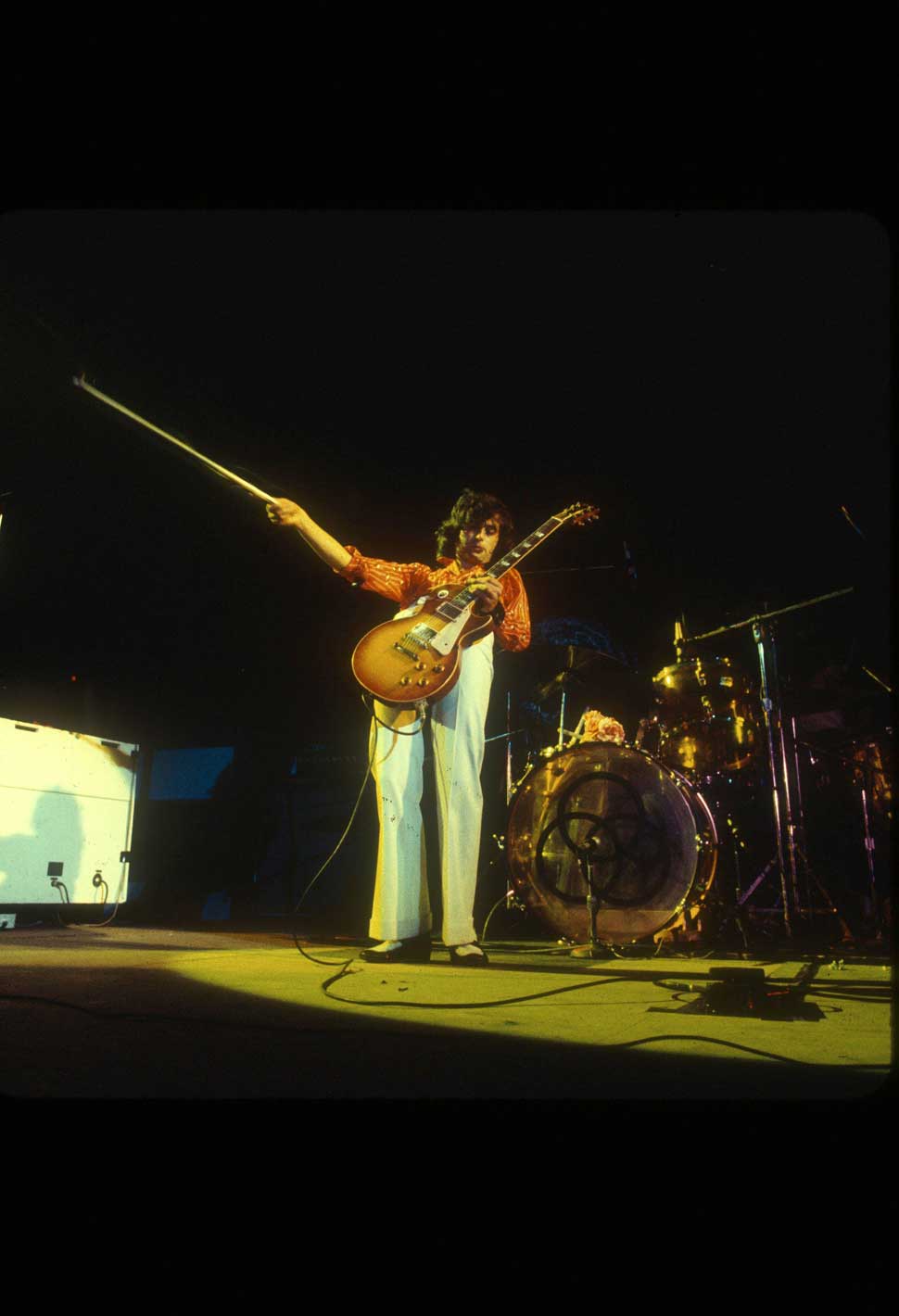

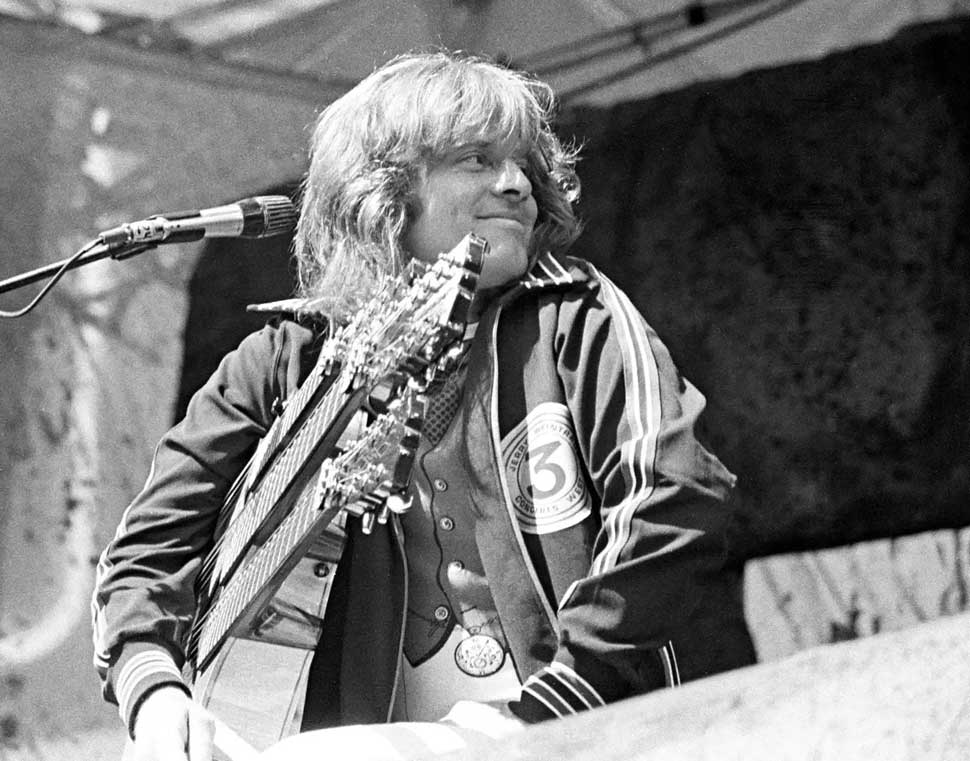

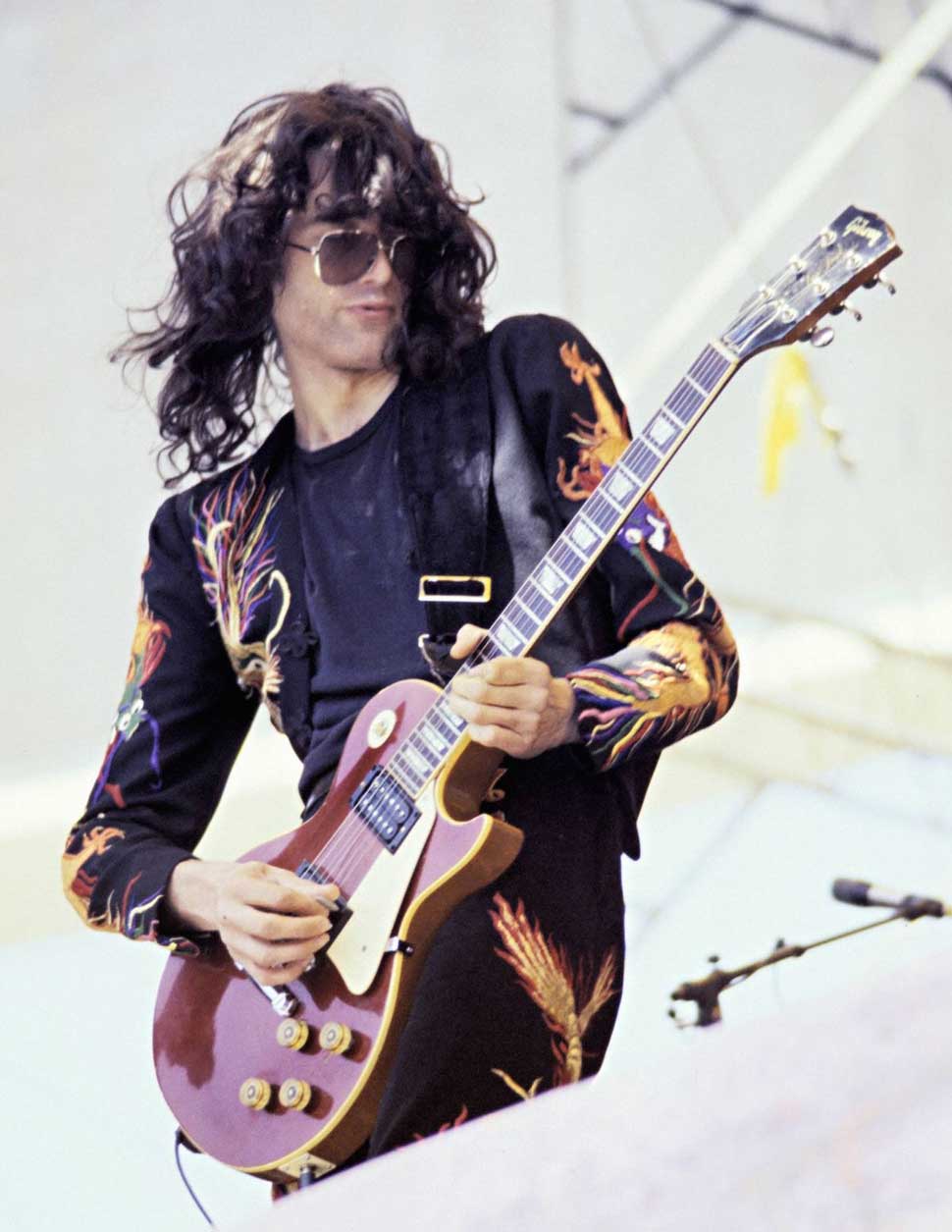

Only a couple days earlier was I finally granted my first audience with Jimmy Page. I had begun to think that it was never going to happen. Then my room phone rang and a voice informed me that Jimmy would see me now.

As I was ushered (you never walked anywhere within the hotel without an escort) into his spectacular suite, it was impossible not to notice the busted telephone hole in the wall and a half-empty bottle of Jack Daniel’s perched on his bedside table. The bottle was up-ended at regular intervals during our conversation, his speech becoming increasingly slurred and deliberate.

This was more than a guitarist getting drunk in the early afternoon – it’s 1977, Zeppelin’s eleventh US tour, and Page’s drinking habits have by now been well-documented. No, there’s more: an underlying current of anger in his every slowly muttered word, as if he’s in a constant posture of self-defence, or even paranoia. In fact, he’s ripped the telephone from the wall because he felt intruded upon and didn’t want spying ears listening in.

“I’ve got two different approaches,” Page explained, as he fiddled with the remnants of the broken telephone receiver. “I mean, on stage is totally different than the way I approach it in the studio. On Presence, I had control over all the contributing factors to that LP; the fact that it was done in three weeks, and all the rest of it, is so good for me. It was just good for everything, really, even though it was a very anxious point, and the anxiety shows group-wise, you know: ‘Is Robert [Plant] going to walk again from his auto accident in Greece?’ and all that sort of thing.”

Jimmy appears to be obviously still feeling the pain of that near-fatal accident. On August 4, 1975, Plant, his wife Maureen, Plant’s sister, their children and Page’s children were all in a rented car that skidded out of control. Robert suffered a broken ankle and elbow, and the children were severely bruised and traumatised.

And so the tour in 1977 kicked off under a black cloud. This is just a small taste of the underlying drama that seemed to envelop every aspect of the tour in a dark mist. No one realised it at the time, of course, but the ’77 jaunt would prove to be Led Zeppelin’s final fully-blown march across America – their swansong.

Upon boarding Caesar’s Chariot for the return from St Louis to Chicago, Janine Safer told me that the all-important follow-up interview with Jimmy may happen on tonight’s flight. You come to recognise, early on, that the Zeppelin machine is well-oiled and finely tuned. Schedules are maintained and rigidly enforced. If anything is going to happen, it’s because Zeppelin want it to – and when they want it to. They wield total control.

A short while later I am told that I can have 15 minutes with Jimmy (on a flight that lasts only 30). After reaching cruising altitude, I’m accompanied to the rear of the plane. Safer is on point, a monster of a security guard follows her, then me, and another security soldier brings up the rear. I greet Jimmy (it’s difficult to tell whether or not he recognises me), sit down, and we begin talking.

“When all the equipment came over here [to the US, for the tour], we had done our rehearsals, and we were really on top, really in tip-top form. Then Robert caught laryngitis and we had to postpone a lot of dates and reshuffle them, and I didn’t touch a guitar for five weeks. I got a bit panicky about that – after two years off the road, that’s a lot to think about. And I’m still only warming up; I still can’t co-ordinate a lot of the things I need to be doing. Getting by, but it’s not right; I don’t feel 100 per cent right yet.”

As I’m hunched over, trying to hear him above the din of the whirring white noise, from behind, a vice-like grip grabs my right shoulder. I’m thinking that was a fast 15 minutes, when I’m physically lifted from the seat and violently spun around. Standing before me is one seriously pissed-off John Paul Jones. And that’s when my world unravels.

“Rosen, you fucking cunt liar. I should fucking kill you.” The venom in his voice staggers me. I feel as if I’m having an out-of-body experience. But each time I shut my eyes and open them I’m still there, standing vulnerable on an aeroplane travelling at 600 miles an hour towards a destination I now don’t want to reach.

Two days ago it had been a different story. John Paul and I had spent some illuminating time together. No Jack Daniel’s, no busted phone, just a soft-spoken bass player telling me about how he met Page and got into this in the first place.

“I’d been doing sessions for three or four years, on and off,” he said. “I’d met Jimmy on sessions before; it was always Big Jim and Little Jim – Big Jim Sullivan [leading session guitarist] and Little Jim [Page] and myself and a drummer. Apart from group sessions where he’d play solos and stuff like that, Page always ended up on rhythm guitar because he couldn’t read [music] too well. He could read chord symbols and stuff, but he’d have to do anything they’d ask when he walked into a session. So I used to see a lot of him just sitting there with an acoustic guitar, sort of raking out chords.

“I always thought the bass player’s life was much more interesting in those days, because nobody knew how to write for bass, so they used to say: ‘We’ll give you the chord sheet, and get on with it.’ So even on the worst sessions you could have a little runaround…”

From there, Jones had got into working from home, arranging material for other people. “I joined Led Zeppelin, I suppose, after my missus said to me: ‘Will you stop moping around the house? Why don’t you join a band or something?’ And I said: ‘There’s no bands I want to join, what are you talking about?’ And she said: ‘Well, look, Jimmy Page is forming a group’; I think it was in Disc magazine. ‘Why don’t you give him a ring?’

“So I rang him up and said: ‘Jim, how you doing? Have you got a group yet?’ [He hadn’t.] And I said: ‘Well, if you want a bass player, give me a ring.’ And he said: ‘All right. I’m going up [to Birmingham] to see this singer that Terry Reid told me about, and he might know a drummer as well. I’ll call you when I’ve seen what they’re like.’

“He went up there, saw Robert Plant, and said: ‘This guy is really something.’ We started under the name the New Yardbirds, because nobody would book us under anything else. We rehearsed an act, an album and a tour in about three weeks, and it took off.

“The first time, we all met in this little room just to see if we could even stand each other,” Jones had recalled of the band’s early days. “It was wall-to-wall amplifiers. Jimmy said: ‘Do you know a number called Train Kept A-Rollin’?’ I told him: ‘No.’ And he said: ‘It’s easy, just G to A.’ He counted it in… and the room just exploded. We said: ‘Right, we’re on. This is it, this is going to work!’ And we just built it up from there. [And now] I wouldn’t be without Zeppelin for the world.”

You couldn’t help but believe Jones. Led Zeppelin was his life and passion and he was forever protecting it, as he told me, from those who would try to run it down. He was talking about critics, in the main, journalists who would tell him how much they admired the band and then turn around and write scathing reviews.

Confronting me now on board the band’s plane was all that passion turned poisonous. The bassist hurls curse after curse. Although I’ve never been in a fight in my life, his veiled threats don’t cause me too much alarm. Jones, I felt, was someone against whom I could probably hold my own. The guys behind him, on the other hand… They shoot me with looks that convey a pretty simple message: make even the slightest motion towards this man before you and you’ll regret it.

At that point I notice there, in his right hand, a copy of Rock Guitarist. Jones has rolled it up into a tube and smacks it repeatedly into his open left palm. On the cover of the book is a picture of Jeff Beck; inside is the Jeff Beck interview I’d written some years earlier. I had brought copies for him and Jimmy; Jones and Page both knew Beck, of course, and I thought the gesture would present me with a bit of street cred.

But it’s this story that has made Jones go crazy. It was my breakthrough as a fledgling writer. In effect, it – and nearly a year’s worth of phone calls to the Swan Song offices in New York – had got me to Led Zeppelin. And now, after getting this close, it suddenly looks like I am going to leave empty-handed. For it’s at that moment that it hits me: the realisation that I have sent Jones off the deep end because I’ve betrayed his trust.

Repeatedly I told him how honoured I was to be on the road with him, and he believed what I said – until he read what I’d written in the Beck piece. The very thing that has brought me here is going to bury me. I had been warned. I should have remembered the fifth rule (‘the band read everything written about them’). For in the intro to the Jeff Beck piece, written three years previously, was the following assessment of Page’s early work: ‘A contemporary of Beck, Jimmy Page has failed to recreate the magic he performed as guitarist for The Yardbirds. Led Zeppelin started off as nothing more than a grandiose reproduction of Beck’s past work…’ and so on. It was stupid and ridiculous, and I’m ashamed to this day for writing it.

John Paul Jones stands before me, demanding all my interview tapes from this spell with the band be returned. I oblige instantly.

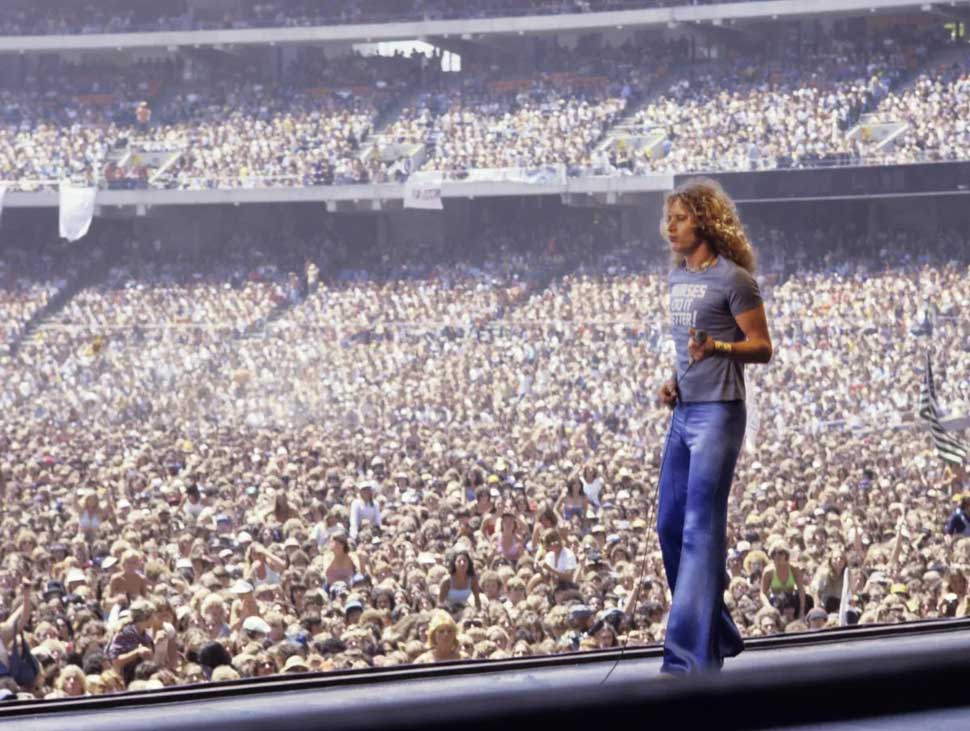

The JPJ encounter would finally resolve itself. But in order to put things in proper perspective it’s essential to understand the juggernaut that Led Zeppelin were at that time. By 1977 the quartet had nothing left to prove and no one left to prove it to. On April 30 that year, the band had set a new world record for the largest paid attendance at a single-artist performance when they drew 76,229 people to a concert at the Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan. The show grossed a staggering $792,361 (also a new record), after having sold out in one – pre-internet, remember – day.

The previous year Led Zeppelin had swept the boards in Circus magazine’s readers’ poll, winning best band, guitarist, vocalist and songwriting team.

Also in 1976, the group released Presence, an album that revealed the band’s complex musical make-up (although it didn’t sell very well), followed later the same year by the soundtrack for The Song Remains The Same, the film revealing personality-through-indulgence. The hedonism it reflected would be carried to ridiculous extremes on Zeppelin’s ’77 tour.

Here was a band that lived life like superheroes. They were treated as kings, and couldn’t see – or refused to see – that they were being devoured by the very machine they had created. But when you were with them, you too became a part of their larger-than-life adventure.

“I’m sure we all felt a little invincible on this tour,” explained Gary Carnes, head of the lighting crew. “By being associated with Led Zeppelin, it seemed impossible not to have a false sense of power. I’m sure the band felt that way, and I know everyone on the road crew had a feeling of being invulnerable.”

I had arrived during the first leg of the tour, which began on April 1 in Dallas, Texas. Notwithstanding the record-breaking attendances and grosses that would come, everything seems filtered through a glass, darkly. No one is able to erase Plant’s near-disastrous car accident a couple years earlier, and now the 51-show, 30-city invasion kicks off a month late due to his contracting a throat infection. Additionally, Peter Grant has suffered through the ignominy, not to mention the emotional pain, of being dumped by his wife.

After only the second performance, in Chicago, Page is taken sick with what Jack Calmes describes as the “rockin’ pneumonia”. Calmes is head of Showco, the company that provided lights, sound, staging and logistics for the tour.

“There was an extraordinary amount of tension at the start of that ’77 tour,” Calmes recalled. “It just got off to a negative start. It was definitely much darker than any Zeppelin tour ever before that time [Calmes was involved in the 1973 and 1975 tours]. Zeppelin still had their moments of greatness, but some of the shows were grinding and not very inspired.”

Indeed, on the four or five performances I saw, the band felt as if they were merely playing by numbers. Although there was no opening act, and Zeppelin often played for more than three hours, the music seemed to have no life, no emotion. Many of the audiences grew unruly during the marathon performances, throwing firecrackers and various other objects at the stage; I saw more than one security man grab an offender and muscle them outside.

Gary Carnes, Showco’s lighting chief, had a bird’s eye view of every show. Sitting on stage about 10 feet in front of Page, he heard conversations, sotto voce, between the guitarist and singer.

“Quite often Robert would announce a song and Jimmy would go: ‘Robert, how does that song go?’ And Robert would sort of turn around and hum it to him. And Jimmy would go: ‘Oh yeah, oh yeah, I got it, I got it.’ Or Robert would announce a song and Jimmy would go into the wrong song. The times when Jimmy couldn’t remember how a song went were very, very rare, but it did happen.”

Besides these problems inside the arenas, there were almost nightly rituals of crazed Zeppelin fans outside engaging in minor scuffles with local police. Prior to the St Louis show, I witnessed ardent but non-ticketed fans attempting to break through barricades. Roaming packs of hard-core Zep devotees threw beer cans and engaged in low-key mayhem.

During one arrival, Peter Grant emerged from his limo and walked over to a group of policemen holding at bay a crowd of rowdy would-be gatecrashers. Though I couldn’t hear specifically what the burly manager was saying, his actions were startlingly clear. He pointed to several of his own security crew and motioned them in the direction of the battling cops. Grant made certain no one entered the concert without a ticket.

Peter Grant, former bouncer and wrestler, was, in many respects, the physical embodiment of a lead zeppelin. Standing over six feet tall and weighing over 300 pounds, he used his intimidating presence to maintain order and keep his charges safe and worry-free. He was highly protective, and by ’77 insanely so. He isolated the band members as much as possible – hence the private plane and the ritualised hierarchy of security, handlers and crew.

He brooked no insubordination from his own people, and with outsiders his brand of justice was swift. His raison d’être was simple: to protect his band and their finances. When a bootlegger or unauthorised photographer was identified, it was a lucky offender who was let off with merely a severe verbal reprimand and confiscation of unauthorised merchandise or film. I never saw an incident escalate beyond that, but I was told about one.

“I took the plans and everything over to the band in England before this tour happened,” Showco’s president, Jack Calmes, recalls. “They had their offices on King’s Road and spent most of the time down the street in the pub. But we had a big meeting upstairs in Peter Grant’s office and they said: ‘Okay, Calmes [purposely mispronouncing his name as Calm-us, instead of the correct Cal- mees], what have you got for this tour?’

"So I stood up and gave my presentation, and showed them all these cool lighting effects and lasers, and said the price will be $17,500 per show. The whole room went dead silent. They looked at the window, and Bonham went over and raised the window – like they were going to throw me out of it. And they might have done it. Then after this drama went on for what seemed like a long time, they all just started laughing, because I’m sure I looked like I was about to shit my pants.”

Zeppelin humour. Well, no one was laughing when John Paul Jones confiscated my tapes. I can understand Calmes’s apprehension because that flight back to Chicago seemed interminable.

On arrival, we returned to the Ambassador East, and I packed my bags for an early-morning flight back to Los Angeles. Menacing scowls from bouncers had told me I was no longer welcome, and I made a hasty exit.

Janine Safer, the group’s publicist, had encouraged me to go and talk to John Paul, to try to explain my side of the story. I went down to his hotel suite, knocked on the door, and as it swung open my mind went blank, and I stood there, once again, like an idiot. As a failsafe, I had written him a letter. I handed it to him. He took it, and shocked me by returning my tapes. He told me he thought I was a low-life piece of shit and that I was the worst writer he’d ever read, but that I did have a responsibility to the magazine.

My Led Zeppelin story appeared in the July 1977 issue of Guitar Player. One evening, about a month after the Zeppelin road trip, I’m at the Starwood club in West Hollywood. I’m sitting with my brother, Mick, watching Detective, the band Swan Song were signing to the label.

Mick tells me John Paul Jones is in the corner and he’s walking this way. I’d told him about the encounter, so I figure he’s just goofing with me. Then I turn around and see Jonesy standing in front of me. I expect some sort of abuse. Instead he extends his hand in friendship. He had read my letter and understood that what I’d written in that Jeff Beck story had come from an inexperienced journalist. He loved the story.

After playing LA, Zeppelin flew to Oakland, North California, for the final dates of the tour. And what happened there breathed new life into the legend of the Led Zeppelin curse. It was a terrible way to finish.

“I was standing right by the trailer when all this went down,” recalls Jack Calmes. “Peter Grant’s kid [Warren] was there, and he walked into a secure area and one of Bill Graham [the promoter]’s guards moved him aside; he didn’t hurt him or anything. The Bindon brothers [John Bindon was a British thief and thug turned actor and security man] and Peter grabbed this guy, took him into one of the trailers, and beat the crap out of him. I wasn’t in the trailer but I was right outside. This guy [Jim Matzorkis] was a pretty tough guy, and they were taking him apart in there.

“The Bindon brothers were thugs who were friends of Peter Grant’s and were on this whole tour as security guards. And they brought an element of darkness into this thing. The only thing I remember about John Bindon is that we were in The Roxy [in Los Angeles, prior to the Oakland shows] and he was in the back corner with Zeppelin, and he had his dick out, swinging it for a crowd of about 50 people that could see it [Bindon was famously well-endowed]. And John Bindon later stabbed this guy through the heart [he was acquitted of murder in ’79]; it sounds like something out of a blues song.”

Tour manager Richard Cole, another principal, takes up the story: “When the band came off the stage, Peter went after the guy with Johnny Bindon. I was outside the caravan with an iron bar, making sure no one could get in and get hold of them, because people were after Granty and Bindon then.

“The next day, the four of us got arrested. Fortunately, one of our security guys knew one of the guys on the SWAT. team, and said to them: ‘These guys aren’t dangerous, I’ve worked for them for years.’ So they asked Peter, John Bindon and John Bonham and myself to meet them. They handcuffed us, took us off to jail, and then they let us out after an hour or so and off we went.”

And if the saga of Led Zeppelin was being played out like an unfinished blues song, this wasn’t the final verse. The ’77 tour had taken a terrible toll on everyone – after Oakland, the band members separated: John Paul remained in California; Jimmy and Peter stayed in San Francisco; Bonham, Cole and Plant headed to New Orleans. Within hours of arriving at the Royal Orleans hotel, Robert received a call from his wife. The last verse was being written.

“The first phone call said his six-year-old son [Karac] was sick,” describes Cole. “The second phone call… Unfortunately Karac had died in that time.”

The song would never again remain the same. In 1979 Zeppelin played some warm-up dates at Denmark’s Falkonerteatret, and in August the two landmark UK shows at Knebworth. About a year later, on September 25, 1980, John Bonham was found dead.

“I will never forget the final words I heard Robert Plant say,” lighting director Gary Carnes sums up. “It would be my final show with them – my 59th. I was on stage at the second show at Knebworth. The band had just finished playing Stairway To Heaven. Robert stood there just looking out over a sea of screaming fans with cigarette lighters. It was a magical, mystical moment. He then walked to the edge of the stage with the microphone, and again just stood there looking. And then he said: ‘It is very, very hard to say… goodnight.’ It was an enchanting thing to witness. I will never forget that moment.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 84 (September 2005)

Steven Rosen has been writing about the denizens of rock 'n' roll for the past 25 years. During this period, his work has appeared in dozens of publications including Guitar Player, Guitar World, Rolling Stone, Playboy, Creem, Circus, Musician, and a host of others.