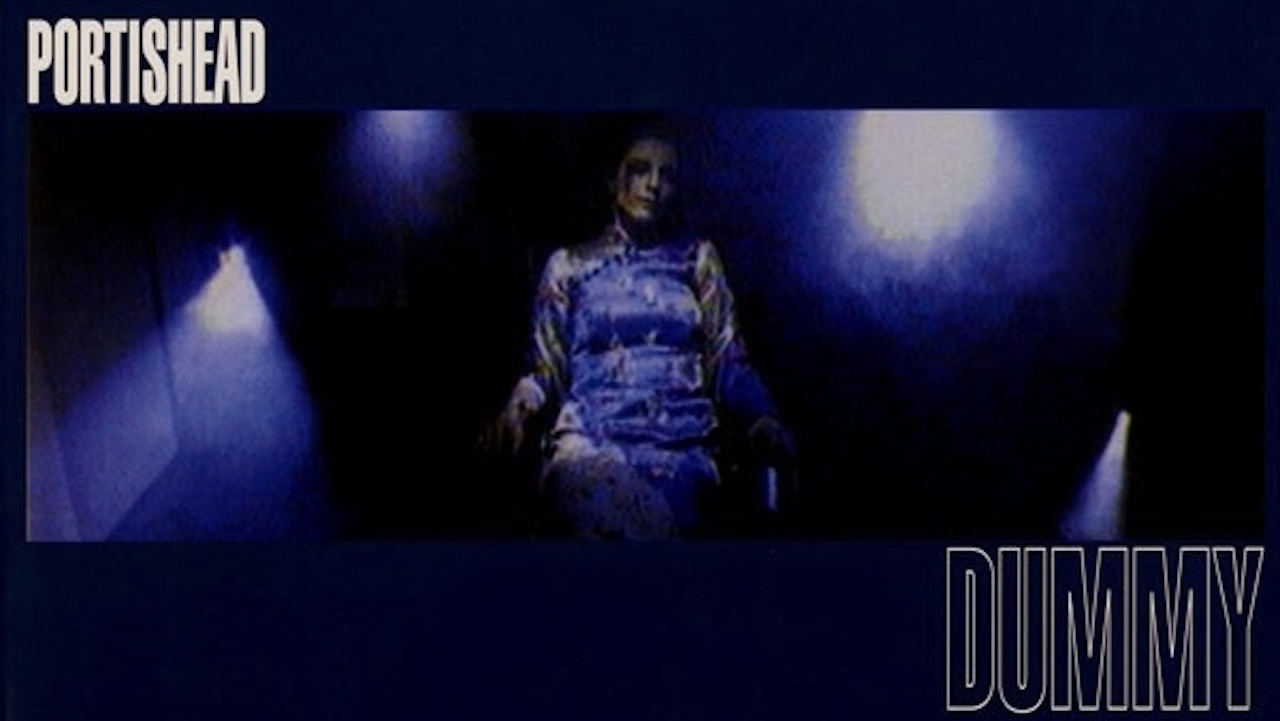

The dark allure of Portishead's Dummy: a melancholic masterpiece from a bleak, alien future

When Portishead released their debut album Dummy on August 22, 1994, it sounded like a transmission from the future. Almost three decades on, it still does

With hindsight, it’s easy to see why 1994 is considered both a landmark year for popular music, and a transitional one. The tragic death of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain on April 5 that year represented a horrific reality check for the grunge/alternative rock community's fairytale takeover of mainstream culture, although the release of Nine Inch Nails' The Downward Spiral and Manic Street Preachers' harrowing third album The Holy Bible proved that there was still plenty of darkness and nihilism for rock to mine.

Into the void left by a scene in mourning, came BritPop in the UK and pop-punk in the US, with emerging stars Oasis, Blur, Weezer and Green Day all releasing landmark albums that year full of life affirming, happy-go-lucky positivity. The after effects of the second 'Summer of Love' saw acid house and techno co-opted into big pop chart hits, even as the highly controversial Criminal Justice Bill sought to destroy it as a counter culture movement, ushering in the rise of superstar DJs. Hip-hop too was undergoing a transformation, with the unflinching socio-political commentary of early gansta drowned out and dragged into the charts by the previous year's Cristal-popping, game-changing Dr. Dre album The Chronic.

But, even in an era where the mainstream reached out to embraced the freaks, the outsiders and the underdogs, Portishead stood apart, the Bristol trio gaining a reputation as enigmatic, shadowy mavericks, even as their debut album Dummy ushered in the first significant commercial interest in the oddly lo-fi mash up of classic soul, jazz, cutting edge samples and gothic noir that would become known globally as trip-hop.

Portishead emerged from a fecund Bristol music scene which took pride in its independence from, and disinterest in, mainstream industry trends and hype.

In the late 80’s, club nights in the city began to feature artists and DJs including Tackhead and The Wild Bunch, the latter collective featuring three members of what would become Massive Attack, who were experimenting with mixing hip-hop breakbeats with early jazz recordings. This would become known initially as 'The Bristol Sound.'

Having moved to the town of Portishead, 8 miles west of Bristol, as a young boy, Geoff Barrow found himself caught up in the movement after landing his first job as a studio hand at Coach House Studios. He worked as an assistant on Massive Attack’s debut album Blue Lines, and, having played in a few bands of his own, decided he wanted to record his own compositions based on the new sound from the surrounding area. Using the spare time he had in the studio; he began to craft what would become the songs on Dummy.

The project began to gain momentum when Barrows met vocalist Beth Gibbons on a coffee break at a 1991 Enterprise Allowance course, set up to give support to young people looking to set up their own business. The pair began to work on music together, recording a version of It Could Be Sweet as their first song. Local jazz guitarist Adrian Utley, who was in the Coach House recording parts for a different project, happened to hear the song being played in an adjacent studio.

“I remember somebody opening the door upstairs and me hearing It Could Be Sweet," Utley told The Guardian. “I was all, ‘Fuck me, what is that?’ Just hearing the sub-bass and Beth’s voice – it was unbelievable. Like a whole new world that was really exciting and vital.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Utley and Barrow immediately hit it off, and the guitarist joined the fold, asking Barrow to teach him everything he knew about sampling and production. In return, Utley would play unique parts on the Portishead project, creating a musical Frankenstein’s monster, where classic jazz and soul samples (everyone from Isaac Hayes to The Weather Report were utilised) would coalesce with Utley’s own guitar, bass, organ and theremin tracks, and Gibbons distinctive folk and rock-influenced vocals.

It took three years to get the album right - the process involved analogue recording of Utley and Barrow’s original musical parts, then transferring them to vinyl, and finally sampling them for the finished project - but upon release Dummy was more than worth the wait.

Debut single Numb, released ahead of the album, didn't dent the charts, but second single Sour Times, broke into the UK top 15, and even made it to number 63 on the US Billboard singles chart. Although a couple of Mo-Wax Records releases, and Massive Attack, had enjoyed a measure of commercial success, there was nothing as dark, melancholic, chilling or threatening in their work as the gothic chime that accompanied Gibbons whispered, pained vocal on Sour Times. At once captivating and completely alien, to hear it was to experience similar emotions to those Utley felt upon hearing It Could Be Sweet.

Much like the music on the record, the success of Dummy was something of a slow burn. Released on August 22, 1994, it slowly crept up the UK charts, and by January 1995 it had reached number three, kept from the top spot by Celine Dion and The Beautiful South, before eventually peaking at number 2.

Its success was helped by the release of third and final single Glory Box, another top 20 hit in the UK, and a song Portishead played live on Later... with Jools Holland. Their performance on that show is staggering: seeing the live line-up of the band, complete with guitar, bass, drums and a DJ, was unique enough, but Beth Gibbons' delivery of the song - eyes clenched tight, gripping onto the mic as her remarkable voice flows from her, part Patti Smith, part Talk Talk’s Mark Hollis - can still make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up today.

Dummy would go on to win the 1995 Mercury Music Prize, beating off competition from Oasis, Supergrass, Tricky, Leftfield, PJ Harvey and many other hugely respected and eclectic artists. The Bristol Sound now had a superstar album, a figurehead and a definitive name; trip-hop, coined in a 1994 Mixmag article focusing more on The Chemical Brothers and DJ Shadow.

“I don’t think with 10 albums of the year you should just judge one album,” shrugged a clearly overwhelmed Barrow in the press conference after the Mercury Prize ceremony. “there could be a bloke sat at home on his organ recording something that is better than any of this stuff. People injected all of their emotions into albums this year... I just expected a free piss up!”

Barrow may not have realised it at the time, but Dummy would go on to be one of the most critically acclaimed albums of the next three decades. It still sounds fantastic. From the second a loose, clean guitar is joined by scratches, drum loops and Gibbons haunted croon on opening track Mysterons, Dummy grabs you and won't let go. From the alien march and Gibbons wail on Strangers, the Mos Def does Ghost Town stalk of Numb, the now iconic, heart-wrenching organ opening of Roads, a song that sounds like the aural definition of heartache, all the way through to Glory Box, a good shout for one of the greatest closing numbers on any album, Dummy remains a faultless piece of work.

More importantly, it still sounds like one band and one band alone; this could only be Portishead. To stand so resolutely in isolation during one of music’s most creative periods is impressive, to remain there three decades later is astonishing.

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.