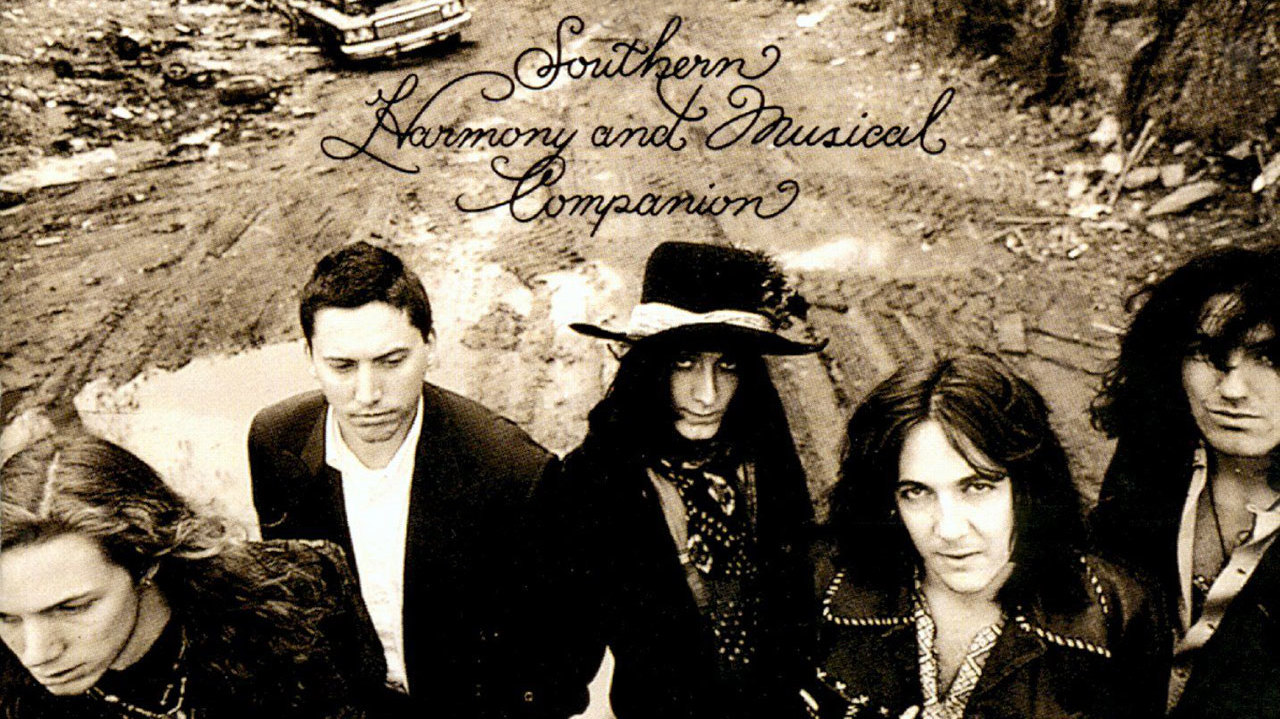

The Black Crowes and the making of The Southern Harmony And Musical Companion

Brother In Arms: the inside story of one of the greatest southern rock records ever made, The Black Crowes Southern Harmony And Musical Companion

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

October 1991, King George’s Hall, Blackburn. The Black Crowes are in Shangri-La. That’s singer Chris Robinson’s description of the bubble of earthly – and earthy – paradise the band conjure up on stage every night. All funky grooves and whirling-dervish soul wrapped in candles and nets full of twinkly Christmas lights, tonight’s Shangri-La is materialising in front of a sold-out audience of 3,500, most of whom surely own a copy of the band’s multimillion-selling debut Shake Your Money Maker and have come ready to sing and bop along to their favourite tunes.

But the Black Crowes aren’t cooperating. After opening with two brand new six-minute songs, they play the hits Hard To Handle and Twice As Hard but then they’re straight back into more unfamiliar material. This is the kind of thing that has driven their handlers crazy over the past year. As the band graduated to headlining status via opening spots for Robert Plant, Aerosmith and ZZ Top (more on all of that later), their manager, Pete Angelus, often stood in the wings, screaming: “Play your damn record!”

But playing their damn record feels like playing it safe. And for the Crowes, playing it safe flies in the face of everything they are and aspire to be. They believe in the Led Zeppelin approach of reinventing yourself and your songs every night on stage. Though it may look like they’re being wilfully uncommercial, Chris Robinson explained, “being true to yourself doesn’t mean safe-earned dollars and security which has nothing to do with art”. In the end, all the onstage experimentation with new material laid the groundwork for what still stands as their finest album: 1992’s The Southern Harmony And Musical Companion.

“We went off and played 300 million gigs, we got out there, we learned a lot, and we came back and we were in a different groove,” Chris Robinson tells Classic Rock. “If you listen to Shake Your Money Maker, everything’s really hard on that one – the rhythmic quality is more like an AC/DC record than a Rolling Stones record. It’s straight. But Southern Harmony is more syncopated. More mid-tempo. Funkier. We could’ve milked the same old thing, but we found a new groove, and that’s what I’m most proud of.”

“Through the repetition of playing live every night, and being under the pressure of opening for Aerosmith and Robert Plant, everything got fused together,” says bassist Johnny Colt. “There was massive pressure to repeat our success. And that pressure actually helped make the band and the second album great.”

“It was the record that gave us a pathway to having a long career,” reckons Chris.

That career began in Atlanta, Georgia, where Chris and Rich Robinson were born into a musical family. Their father, Stan, who Chris describes as “a Bobby Darin type”, had a minor hit, opened for Bill Haley and Phil Ochs, and even played Nashville’s famous Grand Ole Opry. More importantly, dad’s record collection provided his sons with an eclectic supply of inspiration, “from Johnny Guitar Watson to The Yardbirds to the Modern Jazz Quartet”.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Budding poet and bookworm Chris quit college in 1984 to sing in the band started by his guitar-toting 15-year-old kid brother, Rich. They called themselves Mr. Crowe’s Garden. Unmoved by the MTV-approved rockers of the day – Loverboy, Quiet Riot, Night Ranger – the Robinsons looked to the past, covering songs by people such as Love, Gram Parsons and Humble Pie. They practised a lot, and burned through drummers and bassists with Spinal Tap speed. They started writing their own songs, then changed their name. In 1989, The Black Crowes were discovered in a local club by A&R man George Drakoulias, who got them a deal with Rick Rubin’s Def American label. Rick went on to become their producer.

The Crowes’ climb from unknown roustabouts to the It Band of 1991 was slow and steady. Their debut album, recorded on a measly $5,000 advance, gathered steam, as hits Hard To Handle and She Talks To Angels propelled them into constant rotation on rock radio and MTV. They made the cover of everything from Spin to Rolling Stone, who voted them Best New Rock Band. Meanwhile, fans latched onto their throwback sound and swagger – a potent mix of Stones, Faces and Free, all filtered through a southern badass attitude. As an antidote to the bands dominating the charts then – Color Me Badd, Roxette, Nelson – the Black Crowes were akin to the second coming.

Their rise was made all the more entertaining by Chris Robinson’s mouth almighty. Part haughty wrath, part stoner goofiness, Chris was unstoppable, whether calling New Kids On The Block “dripping-nosed, talentless pricks” or rapping on stage about how “The Black Crowes are guilty! Guilty of never kissin’ anybody’s motherfuckin’ ass!”

Chris always gave good quotage and kept the band in the headlines, and never more so than when he got them thrown off ZZ Top’s Miller Lite-sponsored tour in 1990. During the Crowes’ set, Chris made a point of announcing: “This is brought to you commercial free.” Miller complained. The Top’s manager then told Chris to stop. He didn’t. That escalated into him equating ZZ Top’s corporate sponsorship to “prostitution”.

Funnily enough, every time Robinson dropped another one of his verbal bombs the band sold another 30,000 records. Looking back on his mouthiness, Chris says: “As a young person I was arrogant and angry and all that stuff. I’ll gladly accept those things, because it was my right as a 24-year-old rock star who’s making these adult businesspeople millions and millions of dollars at the time of our heaviest commercial moment. Fuckin’ A, what else did I have? They weren’t my friends. They have a hundred bands in their roster. I had one. I think that ‘us against them’ mentality has always included our audience as well.

Rehearsals for the band’s second album began in a time-honoured rock location: the garage. But it was a Crowes-style garage: a scaled-down Shangri-La, with rugs, candles, those twinkly lights and a huge black-light poster of Leon Russell.

“I bought a house in Atlanta and we put the album together in a couple of weeks in my garage,” Chris recalls. “We had about 25 new songs going in. Four or five of them, like Thorn In My Pride and Sting Me, we had started playing by early 1991 when we were on tour. A lot of the other songs were written in bits and pieces, towards the end of the Money Maker tour, in Europe. But we were coming off 350 shows in 18 months, so we were raring to go.”

Before the rehearsals, the Crowes had fired original lead guitarist Jeff Cease – who Chris says was “a subtraction to our music” – and replaced him with Marc Ford from Burning Tree. Rich Robinson commented at the time: “Marc made the songs warrant second guitars, because he could actually play his instrument.”

Ford was indeed a catalyst in pushing the band’s sound forward, not only through the Hendrix-meets-Page fire of his solos, but also in his ability to weave and embroider guitar lines around Rich’s open-tuned chording. Still, Ford’s first day on the job was a real eye-opener. The first surprise was that the Robinsons had completely rewritten the album they’d shown him during his audition a few weeks before. The second came as they started working on Sting Me, conceived by Rich as a slow-burning blues number. Chris told Rich it would be better as an uptempo rocker.

An argument ensued. Tempers flared. Chris picked up his mic stand and took a swing at his brother. “It hit him right in the head,” Ford told Guitar Player in 1992. “Rich threw his guitar down, lunged across the room and grabbed Chris by the shoulders, throwing him up against the wall; glass, candles and books went flying everywhere.” Johnny Colt and drummer Steve Gorman, who’d seen their share of dust-ups between the brothers, stood by. Ford wondered what he’d got himself into. “It was complete insanity,” he said.

“The tension between the brothers always existed,” Colt says. “It was there before we made our first record. The only difference now was that there were a lot of people in the middle – managers, lawyers, label guys. That mucks up the communication. So when there were rifts, it was harder to get them back together. Were the rifts real? Sure. But journalists liked to make them into the new Davies brothers. They made a lot more out of it than we did. We grew up in the south, a culture where people punch each other in the mouth when they’re angry. Marc Ford, coming from the West Coast, had no idea what he was walking into.”

As usual, Chris and Rich made up quickly and got back to the creative matters at hand. As the band woodshedded on the new material, some songs got major overhauls, some were dropped altogether and a few more were composed in the heat of the moment.

“One of the things that you can’t take away from The Black Crowes is that on those first two records we did the work, plain and simple,” Colt says.

Ford reckoned work and a fluid creative attitude were the secrets to their success. “You’re really forced to stop thinking and just trust your instincts to groove,” he said. “It keeps things very alive and on the edge. And it either works magically or falls apart.”

Phase one worked magically. From the garage, the band moved to Atlanta’s Southern Tracks Recording Studio where they were joined by producer George Drakoulias. Sessions began in January 1992.

In the world outside, US President George Bush got ill and vomited on the Japanese Prime Minister. The Space Shuttle Discovery 15 launched. And in LA, racial tensions were heating up, stoked by the impending trial of four white policemen accused of beating African-American Rodney King. The opening lines of the new album would prove prescient: ‘If you feel like a riot, don’t you deny it.’

Over the course of what Chris Robinson calls “eight hazy days”, the band recorded the entire album to 24-track tape. That’s not bad in an era when it routinely took Def Leppard three years to make a record.

“Again, we’d done the work on the front end,” Colt explains. “We walked in the studio totally ready. A real rock’n’roll band who can play and who toured the way we did? If you can’t cut your record in eight days, something’s wrong with you.”

Colt, Gorman, Ford and new keyboardist Eddie Hawrysch had to be on their toes. “It took all I had to concentrate on where to put my hands and just get through the songs,” Ford said.

Colt: “In Chris and Rich, you had two super-good songwriters trying to figure things out. The rest of us were there to help give each song legs. For me it was just day after day, hour after hour, trying to make whatever we were working on sound its very best.”

Rich summed up the band’s approach to the new songs this way: “Everything on the album is unconscious. Sometimes I’m afraid to go back and analyse how I wrote something, because I’m afraid I’ll start to subconsciously try to repeat some formula.”

That unconscious approach produced a wealth of memorable material. From the one-two, uptempo punch of openers Sting Me (Chris won the argument) and its soulful cousin Remedy, through the melancholic beauty of Bad Luck Blue Eyes Goodbye to the strut and swagger of Hotel Illness and No Speak No Slave, to a New Orleans-flavoured take on Bob Marley’s Time Will Tell, it was the exhilarating sound of a band hitting its stride.

Funky, artlessly noisy, loose and tight in perfect measure, with stomping beats, church-y female background vocals, and dual guitars snaking around Chris’s raspy howl, it echoed everything from Exile-era Stones and Nick Drake to the Allman Brothers. More than anything else, though, it sounded like The Black Crowes. They found their “own language”, says Chris.

“What Chris accomplished in the lyrics was so authentic to who and what we were and where we came from,” says Colt. “I felt like he tapped into our fucking southern cellular DNA.”

Chris: “As a kid I was a horrible student, and I dealt with really severe dyslexia and trying to put it all together, and being a weirdo. But I had music and writing. That’s where I could express myself. That’s where I could be honest. I knew enough about who I was and what I wanted to do with music that I wasn’t going to be swayed easily by sycophantic gestures.”

On one song in particular, Black Moon Creeping, that honesty edged towards a darkness that Chris hadn’t addressed before. So ominous was the track, one of the female backing singers walked out of the session, saying: “I’m prayin’ for y’all. You need it.”

Chris chuckles. “Everything was still very new at the time, so the light and the dark was very new, and we were very attracted to dark matters. Even though I was 24 years old when that record came out, we did have the money to blow our minds. The drugs did start to be a bigger part of the sound and a bigger part of our experience. With that came the cast of characters and dealers and women and all sorts of weird stuff. There’s a dark romanticism with your youth. At least for me. When you grow up it’s Alex Chilton and Syd Barrett. When you look up to those guys, how far are you gonna go?”

- Rich Robinson forms The Magpie Salute with ex Black Crowes men

- The 10 Essential Southern Rock Albums

- Black Crowes split in ownership row

- Read Classic Rock, Metal Hammer & Prog for free with TeamRock+

Chris recalls that the band wanted to carry the spontaneity and freedom of the tracking sessions right into the mixing: “I mixed Thorn In My Pride with our engineer, Brendan O’ Brien, at the Record Plant in LA. And I hated it. They had this huge board with digital computers and shit, which Brendan loves. Forget it. I went over to Hollywood Sound, got on that little Neve board and hot-mixed the whole rest of the album in one evening. What else do you need?”

The result was a record that sounded like a classic – albeit a classic in 1974, not 1992. Their label, Def American, didn’t hear a hit. “When we plopped the record on their desk, they were definitely freaked out,” Chris laughs. “But if anyone told me anything back then like: ‘You’re making a mistake,’ I said: ‘It’s mine to make, not yours.’”

Colt remembers that the label “pounded us to do a cover song, another Otis Redding or some other razzle-dazzle bullshit. But, you know, when we turned the first record in, the reaction wasn’t positive either – Rick Rubin didn’t even put his name on it. I like Rick, so I’m not gonna bash him, but he thought we were a bunch of girly men dressed in ruffles, playing a rock’n’roll that wasn’t hard enough. He didn’t put his name on the record until it sold like 500,000 copies. But no one’s ever excited about your record when you turn it in. It’s lightning in a bottle. If they knew anything, they’d own the business. The only thing they can do is send you back to redo it, so if it is successful, they can say they had a hand in it.”

“If I’d listened to everyone saying we needed to go back in the studio, what would’ve happened?” Chris poses. “There was just a spiderweb’s chance that I would be here talking to you 20-something years later in my career. That doesn’t happen, at any level, regardless of any kind of success. So at that time, being 45 years old was hardly in my consciousness. We were doing what we felt. No Speak No Slave was a direct song to that feeling. For us it was about telling us what to do. The reality is that we would’ve lost out if we’d followed their advice.”

The new album was named after a post-Civil War southern hymnal, The Southern Harmony And Musical Companion. Released on May 12, 1992, it entered the US Billboard album chart at No.1.

“The record debuted at No.1 and went on to sell millions of copies, and was our real success in Europe. And I think with people who are into The Black Crowes, it’s our finest record, our classic album,” says Chris. “But it was a failure at the time for the record company because it didn’t sell more than Shake Your Money Maker.”

In support of Southern Harmony, the band set out on a year-long tour. There would be trouble in the decade ahead that left the band, in Colt’s words, “tattered and torn”. But right then, they were kings.

“As far as I’m concerned, from 1992 to 1994, no one could touch us in the studio or on stage,” Colt offers. “If we were a prizefighter, that would have been our golden moment. We were the Floyd Mayweather of real, authentic rock’n’roll. And Southern Harmony is a definitive statement about being young, coming into your own as an artist, being southern. In my opinion, it’s one of the greatest southern rock records ever made.”

“The thing I’m most proud of is that’s where we made a stand,” Chris says. “That’s where we went from looking from the outside in, to being inside looking out, in a way. Although it comes with a price, like growing up always will for anyone, no matter what you’re doing. It was the record that pointed the way forward for us.”

He pauses, then laughs, saying: “It also set the stage for us being the biggest pains of asses of all time. But, you know, so what?”

This feature originally appeard in Classic Rock 182.

The Magpie Salute: Former Black Crowes Rich Robinson and Marc Ford fly again

Bill DeMain is a correspondent for BBC Glasgow, a regular contributor to MOJO, Classic Rock and Mental Floss, and the author of six books, including the best-selling Sgt. Pepper At 50. He is also an acclaimed musician and songwriter who's written for artists including Marshall Crenshaw, Teddy Thompson and Kim Richey. His songs have appeared in TV shows such as Private Practice and Sons of Anarchy. In 2013, he started Walkin' Nashville, a music history tour that's been the #1 rated activity on Trip Advisor. An avid bird-watcher, he also makes bird cards and prints.