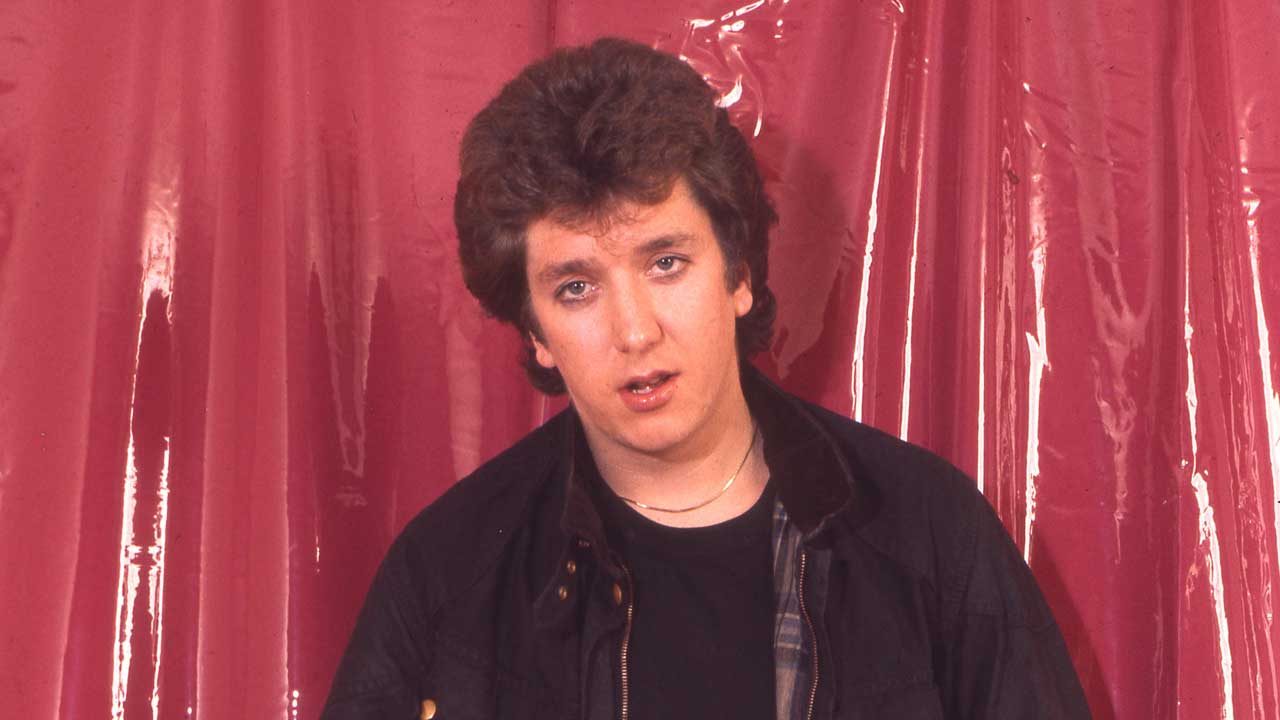

Steve Jones: the Classic Rock interview

Now in his mid-60s, and with the ups/downs life experience of someone at least twice his age, the former Sex Pistols guitarist who changed the world says: “I don’t want any aggro at this stage of the game. I just wanna have a good time.”

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

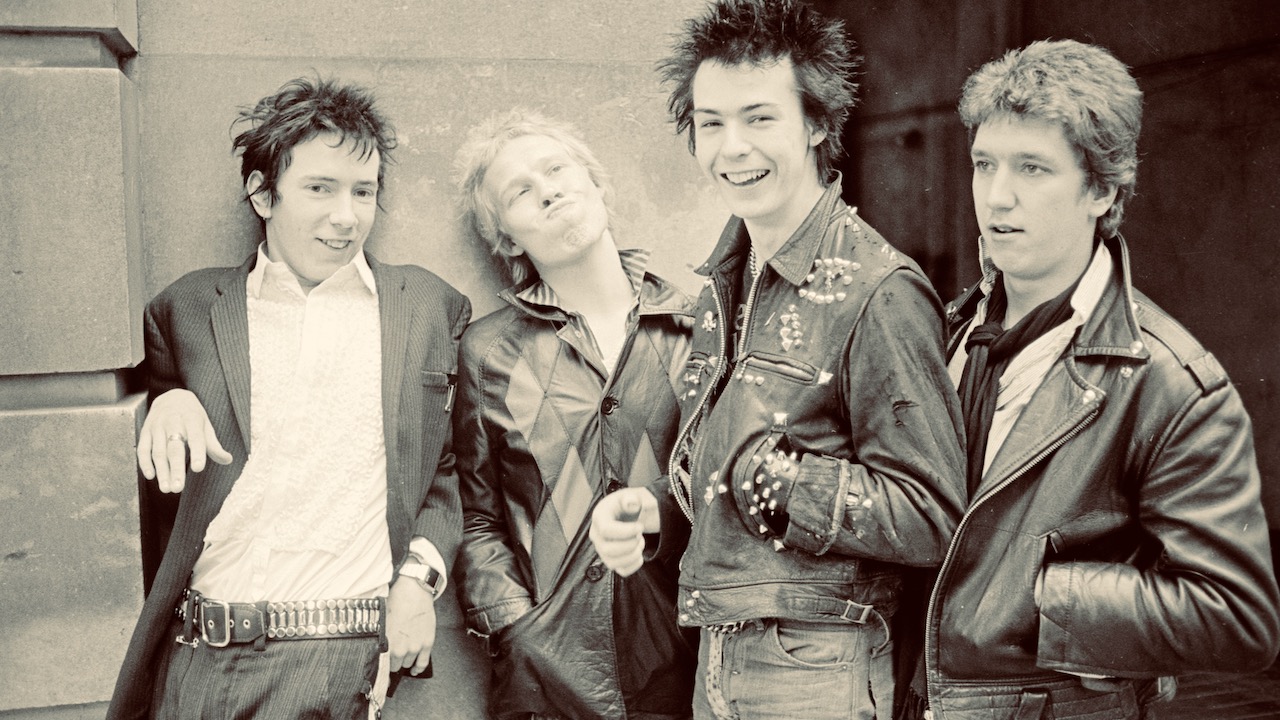

The Sex Pistols saved Steve Jones from a life of crime. Born in Shepherd’s Bush in West London, and abandoned by his father at age two, Jones was raised by his hairdresser mother and a sexually abusive stepfather in Hammersmith. Functionally illiterate, he found solace in theft. Fourteen criminal convictions later, he was remanded to an approved school, where he fell in love with the Faces.

Once back at large, he met Malcolm McLaren, learned to play guitar, formed the Sex Pistols with equipment stolen from David Bowie’s farewell Hammersmith Ziggy show, and subsequently changed the world. Since the Pistols split in ’78, Jones has played with everyone from Guns N’ Roses to Bob Dylan, conquered addiction and enjoyed a second career as host of LA-based radio show Jonesy’s Jukebox. His extraordinary autobiography, Lonely Boy, has just been adapted for the small screen as six-part mini-series Pistol by Academy Award-winning director Danny Boyle.

With your birth parents both being Teds, is rock’n’roll in your blood?

Yeah. I definitely got my rhythm from my mum. She had a lot of spunk in her when they used to go down Hammersmith Palais. I don’t really know my real dad, but I must’ve got my good looks from him.

Your early years living with your mum and grandparents seemed idyllic, but from the arrival of your stepfather your life seemed to go into free-fall. Was hearing Jimi Hendrix’s Purple Haze coming through your neighbours’ window like a portal into another world?

I loved music from a very early age. Liked it more than most kids. To them it was just a noise, but I gravitated to it. I don’t know why it was so important to me. Some people are just more musical than others. Some people can go through life without even listening to music. Some people are happy to listen to whatever’s on the radio. I always like to search for more.

You’ve known [Sex Pistols drummer] Paul Cook just about forever. Why do you think your friendship has endured?

I used to see Cookie walking to school when we were about ten. We were both skinheads, and that was the first attraction because there wasn’t many people dressed like skinheads then, especially as young as we was, so we knew we’d probably get on. We were good for each other, our personalities. I was always the one wanting to explore, and Paul was happy just to tag along. We just had great chemistry, and we’re still good pals. I guess there’s people who are friends for life, and he’s one of them.

Being a skinhead, what you wore was suddenly very important. Was nicking clothes what started you thieving?

I don’t know why I started nicking, other than I was subconsciously unhappy with the circumstances of my upbringing, with the step-dad and my mum, who just catered to him and didn’t really care for me. That’s the impression I got as a child. And I used to see them nick in Tesco – I used to watch them put fucking things under their coat. So it just seemed normal.

Tell us about the Steve Jones Cloak Of Invisibility.

I used to think I was invisible sometimes. Even around people. It was the weirdest thing. I’d go to Hamley’s, and rather than thieve from the shop floor I’d walk into the stockroom. I was convinced that if people saw me they’d’ve thought I worked there. Even though I was, like, eleven, which is ridiculous. But I never got pulled in there.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The cloak wasn’t infallible, because you ended up in Banstead Hall approved school. And there you discovered Rod Stewart and the Faces.

I got into the Faces through Rod’s Every Picture Tells A Story. I actually bought the album in the HMV on Oxford Street. I just loved the cover. I was infatuated by Rod: the barnet, the boat race, the voice and the clothes. And I was so happy with myself that I saw this album, bought it, and then it became a massive album. There was something satisfying in that, telling myself I liked good music. I was just hooked by Rod. Then the Faces, same deal. A great band to watch live. It was like a good time, it wasn’t all serious pomp. I loved them.

Where did you get your first guitar?

I can’t remember where I got it, but it was the Les Paul, and I gave it to Wally Nightingale who was wanting to put a band together. Me, Cookie and him would sit around his house, and we thought we were the Faces. He’d come up with riffs and I’d try and piddle along – I had no clue. They pushed me to be the singer. And I thought being the singer would be easy because I wouldn’t have to learn anything. I only really started playing after we got rid of Wally and I got put on the guitar. That was when I had to pull my socks up. And that was the beauty of the black beauties [fuelled by prescription diet pills, aka black bombers/black beauties, Jones taught himself guitar by playing along with The Stooges’ Funhouse while living in a squat above the fledgling Sex Pistols’ rehearsal space in Denmark Street]. I had ADHD – a lot of kids have it now, but there wasn’t a name for it then – but the speed gave me focus. I had a little record player I’d play along with over and over again. I just used to fuck about. I didn’t know what I was doing.

You met future Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren in 1971 when he and Vivienne Westwood were running their shop on the King’s Road, then called Let It Rock and ostensibly catering for Teddy Boys, and they let you into their home. Did they become surrogate parents for you?

Yeah, you could say that. It was good for me because at this point I never went home. I’d stay at Cookie’s with a couple of other people, and then when Malcolm came into the picture I could stay there too, and it was great. The great thing about Malcolm was that he had this other life I’d never known. He went to The Speakeasy, the club everybody went to back then, and knew all these King’s Road avant-garde types. I’d just tag along, and I was fascinated by it, just being an ’erbert from Hammersmith, and I loved it. And he liked having me around. He couldn’t drive, so I drove Viv’s Mini to the tailors in the East End so he could pick up samples. I always feel my loyalty lies with Malcolm. Even though we got shafted on the business end of it, I just had a loyalty to him. I liked hanging out with him, he was a laugh.

Because you were so close, would you have taken him to court over the missing Sex Pistols money if John Lydon hadn’t started the ball rolling?

Probably not. It was a great move on John’s part. Well, them two never saw eye to eye, really. But I’m grateful to John for that.

John Lydon – there couldn’t have been a Sex Pistols without him. But you never really know which John you’re going to get, do you?

I love John. I’ve a deep love for the guy, but I don’t wanna hang out with him. He can be hard work, but I obviously admire what he brought to the table. He was unquestionably brilliant, the full package: the look, the great lyrics, he was sharp as a diamond back then, and of course it wouldn’t’ve taken off without him, never. But I think we all played a big part.

The punter that Vivienne originally recommended to front the Pistols turned out to be Sid Vicious. Do you think we’d still be talking about the band now if Sid had got the job and John had never been brought in?

No, not in a million years.

Concerning the ‘Grundy incident’ (brought on as a last- minute substitute for Queen, the Sex Pistols famously swore on Thames TV’s teatime current affairs show Today, presented by Bill Grundy, in December 1976), do you wish it had never happened, and the band could have developed outside of the tabloids’ glare, without the bans and notoriety?

The truth is, it was what it was. It was short-lived and that was it. I don’t regret what happened. At the time, the Grundy thing was amazing. What happened after was so exciting. But unfortunately it was the beginning of the end. It just became a circus, and it was hard to handle. Then Glen [Matlock, bass player] leaving, and Sid joining, who couldn’t play... He looked fucking great, but it was slowly deteriorating. And then in America we all went our separate ways. It wasn’t a band, and it seemed obvious to implode. I’d had enough by the time we ended it in America. In hindsight we should’ve just had a rest, then gathered around again, but I was done. Literally.

While having Sid on bass was difficult on many levels, his lack of interest meant you were able to put your stamp on Never Mind The Bollocks. You played bass, and seemed to work closer with producer Chris Thomas than anyone else on creating that Sex Pistols sound.

I would’ve loved Sid to have played on the record, but he just couldn’t. He was in hospital with hepatitis, so someone had to play bass and I just stepped up. He started out focused on learning where to put his fingers, but after a while he thought he was playing guitar; you can’t do power chords on the bass, but he seemed to think he could. So that was a bit of a nightmare.

It’s amazing to think we’ve had forty-five years of punk bands trying to recreate that Never Mind The Bollocks sound and no one’s really succeeded.

Well, me and Cookie definitely have a chemistry when we play together, like Charlie Watts and Keith Richards. Something happened when they played together, and I think it’s the same with me and Cookie. There’s a mental communication that just seems to work.

How much creative input did Malcolm actually have into the band, and do you think he was more responsible for the break-up than Sid was?

He had nothing to do with the music, not one iota, but he was important, a great manager who saw opportunities. Sending us to the American south when he did may have seemed mad, but we got a ton of publicity out of it. He didn’t want any of that ‘here comes another rock band’ crap, and as much as I fucking hated playing in front of people slinging bottles, I get the concept. Everything was a stunt. Just playing a gig in front of a bunch of people was boring to him. But he probably had something to do with the demise. He might have wanted it to end. Then again, why would you bother managing Bow Wow Wow or Adam Ant if your goal was just to destroy bands?

By the time he was managing Bow Wow Wow he’d started to believe his own legend and wanted to have creative input, to write lyrics and give artistic direction, but it wasn’t really what he did best.

No, but he did want to be a star. Which he obviously couldn’t be. Everybody wanted to have a go at stardom back then. Even [Clash manager] Bernie Rhodes wanted to be in The Clash. And the opportunity was there, because the doors were still open at that point.

Even though Sid’s story was a cautionary one, you fell into heroin addiction after the Pistols’ break-up.

After we broke up, smack was the perfect remedy for me – just to fucking check out, not deal with it. I don’t know if it had anything to do with the Pistols, I think that was just my destiny anyway. Being an alcoholic and having a shitty upbringing, doing smack was the perfect thing for me. But I’m fucking grateful that I’m thirty-one years clean and sober, because a lot of junkies don’t make it.

Between completing the Pistols film The Great Rock ’N’ Roll Swindle and launching The Professionals, you were a gun for hire, working with Chrissie Hynde, Johnny Thunders, Thin Lizzy, Siouxsie And The Banshees, Joan Jett and, for a short while, Sham 69 frontman Jimmy Pursey. Could a Sham Pistols have ever worked?

No. It didn’t seem like a bad choice at the time, because he was a frontman, he was Jack the lad. But when we tried it there was no chemistry, it had nothing. We gave it a go, but I didn’t give a shit about anything, I just wanted to get high. I wasn’t focusing on a career, even in The Professionals. It was just something to do because I didn’t have anything else to do. I just wanted to be fucking stoned the whole time, I didn’t wanna feel.

You did manage to make an album with The Professionals, but left following an American tour to stay in the States. Had life in England become too junk-focused?

Yeah. Coming to somewhere where there was always sunshine was attractive, and leaving grim London behind, all the junkies, was a no-brainer. I was in New York for a year before I drifted to California. Doing dope there was a totally different scene from London, a lot more dangerous. I must’ve looked like a fucking fish out of water in Alphabet City.

You then spent a couple of years in Chequered Past with Michael Des Barres, but by your own admission you “didn’t give a shit about the music by then”. Did the smack even rob you of that?

Completely. We did a showcase at New York’s Peppermint Lounge, and someone said: “Let’s start a band.” I’m a junkie, so I’m like: “Yeah, okay, great,” but all I’m thinking is where can I cop, where can I get money. Chequered Past brought me out to LA and I cleaned up. I went to this fancy methadone clinic in Century City and got off the smack. I was still drinking like a fish, doing blow and all the rest of it, but I quit smack for a bit. I sold my passport as well, as you do.

When was it you did actually fall back in love with playing?

Only when I got sober. That was the turning point. I look at it like I had two lives: there was pre-sobriety and post-sobriety. Everything changed. It was a long road, but I’m so grateful I managed to fall into the path of sobriety. I’ve always been a sad sack, really, a lonely boy, you know?

Your debut solo album, 1987’s Mercy, was your first release after getting clean, and it featured a Steve Jones we hadn’t seen or heard before. This was a decidedly more mellow Steve Jones. Did you see it as a new start?

Yeah, I wanted nothing to do with my past. It’s an okay album, it’s not great, but it was a start. Whether it was wrong or right, it was just part of my journey towards getting better.

Having worked with Iggy Pop and Bob Dylan, you formed Neurotic Outsiders and took the Sex Pistols back on the road in 1996.

I loved the reunion, because we never really played before, and we definitely didn’t make any wedge. So that was all great and I did enjoy the shows, but I think we played too long. It got ugly at the end. It burnt out. It was great at the time, but I’ve got no interest in doing it any more.

Were you surprised by how good you were on Jonesy’s Jukebox? You’re a natural.

I didn’t have a fucking clue when I started, but I loved it. I’m just like the uncle in the living room who wants to turn you on to new songs. When I started on Indie 103.1, it caught on like wildfire. People were relieved there was something real on the radio, because at that point [2004] everything was already dictated by playlists, and I’d just be loose, have a laugh, say whatever came into my mind, and not take myself too seriously. This was before every Tom, Dick and Harry musician had a radio show, so it was perfect timing. I put it down to someone fucking looking out for me; I just wander along and good things happen. I try to be a decent person, so I’m sure that helps karmically.

How closely is Danny Boyle’s Pistol based on Lonely Boy, and are you happy with how it turned out? Is the bloke playing you handsome enough?

He could never be as handsome as the real Steve Jones, but Toby Wallace did a great job. I can’t wait for people to see it. It’s fucking great.

The attention to detail is amazing. Having (punk legend) Jordan on board guaranteeing a high degree of historical accuracy really paid off, because it’s important for the people who were there at the time to be able to suspend their disbelief.

It’s not a documentary, and some people will probably pick holes in it – they’ll be like: “That didn’t happen at that time” or whatever, but you’ve got to forget that and just look at the big picture. Just look at it as a TV show, and it’s pretty spot-on. And the screenplay... Craig Pearce and Frank Cottrell-Boyce did a great job. I’m so excited.

You’ve recently been playing with Billy Idol, Tony James and Cookie as Generation Sex. Are we to understand that, especially following John Lydon’s failed Pistols court case, you’re not likely to be playing together again at any time in the future as the Sex Pistols, but Generation Sex is there to fulfil a similar role for the fans?

I dunno, it was a lot of fun. We did a couple of shows, and it’s always a possibility down the road, to maybe come to England and do some shows, do a US tour, and I’m up for that because it’s just fun. I just wanna have fun. I don’t want any aggro at this stage of the game, I’m fucking sixty-six, I don’t want to be around anything negative. I just wanna have a good time.

Looking back, are you happy with how everything has turned out? Because yours is a story no one could have made up.

I really don’t know how to answer that. I mean, I’m grateful, and I’m over the moon that I’m still around, and that I’ve kind of got my shit together, but I don’t think I’ll ever be really... I have days of real joy and happiness, but whenever I look at yesterday, I always look at it as kind of depressing. I think I have a little bit of depression, and a loneliness, and I don’t think that’s ever gonna go. I’m always the loner. I don’t have a partner, I have really close friends who are like family, that I hang out with all the time... It’s just what I got dealt with, and I’m not whining about it. I don’t play that victim role, it just is what it is.

I was going to ask you about regrets, but the root of many of your life’s difficulties isn’t really something for you to regret. You got dealt an abusive stepfather, and a difficult childhood – it wasn’t a situation you could have changed yourself.

Yeah, I don’t regret... A lot of kids get dealt a lot worse than I did. Some horrendous shit happens to some kids. My whole thing is that I’ve let all that go. There’s no resentment. My stepfather, my mother, I’ve just let it go... You’ve gotta move on. You can’t be a victim all your life. You can’t keep using that, you’ve got to let it go. I’m left with a certain emptiness about it. My upbringing, my youth... But I’ve really got nothing to complain about.

You’ve had quite serious heart issues in recent years. How do you deal with the anxiety of that, especially living alone?

I’m always the loner, always, but in recent times I don’t like being alone. The heart attack really put me in a different space. I used to get panic attacks, anxiety. That was in 2019 and I’m a lot better now. I just have to pick and choose where I put my energy, and limit what I do now. So you should think yourself really lucky that you got this interview [laughs].

Pistol is available to view on Disney+. Sex Pistols: The Original Recordings is out now via UMC.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.