Southern comfort: the unconventional story of Blackberry Smoke

Southern rock road warriors Blackberry Smoke want you to know there’s more to their music and their homeland than dog-eared clichés and ill-fitting stereotypes

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

One loud Sunday night in the 90s, at a rock bar called the Nine Lives Saloon in Atlanta, Charlie Starr was born. Not literally, of course. But as the young singer/guitarist christened Charles Gray thrashed out AC/DC, Rolling Stones and Motorhead classics, his bandmate inadvertently gave him the name that the rest of the world would come to know him by.

“He and I had a cover band that played there every Sunday, and he started calling me that on stage,” Starr recalls. “And this was over a period of a few years, so people started calling me that all the time. I never really thought about it as a ‘stage name’ per se, or a persona. It’s nothing like that, it’s just a nickname that stuck.”

Nickname or otherwise, it pairs well with the affable frontman’s southern timbre, Keith Richards threads and beautiful vintage guitars (all of which are on display on our Zoom call) – the sort of romantic rock-star ideals upon which rock’n’roll was built, with songs to match. It worked for the Stones, and it works for Blackberry Smoke.

“We’re firm believers in not overthinking much,” drummer Brit Turner, all shaggy beard, glasses and trucker cap in the Atlanta sun, reasons on a separate Zoom call from his van. “I think people can tamper with the music so much that it doesn’t sound real.”

They make good on that ethos on their seventh album, You Hear Georgia, part celebration of the dulcet nostalgia they do so well, part love letter to their motherland, and, in the title track, an exasperated look at the Deep South stereotypes embedded in American culture. Straight-shooting matter with a wry edge.

If you like Blackberry Smoke, You Hear Georgia won’t change that. But there’s more to this band of rock-steady longhairs, and to their home turf. Their story is riddled with sharp edges, little darknesses and intrigue. From a foundation of blue-collar grit, Bible Belt hoodoo and fast-living early days, their sound has been shaped by the nuances of the American south, with a little help from the British Invasion and 80s MTV. It’s the story of how a livewire guitarist from Alabama and two metalhead brothers (drums and bass) founded the 21st century’s answer to Lynyrd Skynyrd.

But first let’s rewind just a year. Like the rest of us, Blackberry Smoke hunkered down with their families when COVID hit. Keyboard player Brandon Still had a baby. When it was safe to do so the band played socially distanced gigs and drive-in shows. Starr wrote songs – a lot of songs.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I have hundreds of ideas on my phone and on scraps of paper,” he says. “I wrote a lot of songs during lockdown for Blackberry Smoke, and also co-wrote a lot of songs with friends. People would sit around bored and say: ‘Let’s write some songs.’ Who knows where they’ll wind up. But it was a really productive period.”

Recorded in Nashville with Dave Cobb (Rival Sons, Jason Isbell, Chris Stapleton) producing, You Hear Georgia comes with an ensemble-y feel, with additional musicians (longtime touring guitarist Benji Shanks and percussionist Preston Holcomb), A-list guests (Rickey Medlocke and Warren Haynes are among Starr’s co-writers on the record) and backing singers the Black Bettys creating flavours of the Tedeschi Trucks Band and Little Feat. From the first notes, there’s a sense that you’re in good hands.

“It was always my dream to have a three-guitar band like Lynyrd Skynyrd, you know?” Starr says. “Over the years Shanks would come and play with us, and it was always so great. This time we were just like, let’s invite everybody, let’s have a party.”

Over the years, Blackberry Smoke’s warm, inviting brew of countrified rock and select spices (swampy slide, Delta hues, metallic edges…) has matured and sweetened, but ultimately not changed a great deal, and You Hear Georgia is no exception.

It’s an approach afforded by independence (they put out music through Earache Records in the UK but essentially retain total control over their operation), and a fan base, affectionately known as ‘the brothers and sisters’ (a nod to the Allman Brothers album?), who continue to buy their records and fill the generously-sized theatres they play.

“Each time gets a little more comfortable,” Turner reasons. “But this, I felt like working with Dave Cobb was magical. He gets what we do. I feel like he just let it happen.”

‘Comfortable’. That’s a word you’ll hear a lot from Blackberry Smoke. You’ll also hear it being used about them by fans and critics, respectively as a redeeming quality and a dull one. Listening to their records and watching their shows – the rock-steady harmonies, the effortless live chemistry, the Skynyrd-style rugs on stage – ‘comfortable’ invariably comes to mind. Is it necessarily a bad thing?

“I guess if we felt the need to change anything about what we do, we would,” Starr says simply, “but I think we come from the ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ generation.”

He pauses and laughs, then adds: “And I don’t know if we’ve ever been given any good advice! We’ve had to learn the hard way in so many instances, and come out the other side with our little notebook full of: ‘Next time don’t trust the guy that bribes government officials’ and ‘Don’t wait three years to…’ you know. The list goes on and on and on.”

Today Atlanta is part of the Blackberry Smoke brand. In a city where rock, metal, hip-hop and more rub shoulders, the band have become part of the furniture. The Black Crowes are their neighbours, as are Mastodon and their families (“We run into each other at Target with the children,” Turner tells us).

But it all began outside the city. Starr grew up in Lanett, a tiny cotton-mill town near the Alabama/Georgia border, where he split his time between a bluegrass-playing father (who worked in a body and paint shop by day) and a mother who loved The Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. Typical of that part of the South, there was little to do. High-school football was a big deal. There was no music scene, except for the bars where as a teenager Starr would play covers sets on Fridays and Saturdays, playing music “to put people on the dance floor and sell beer”.

Before that, aged 11, he had discovered Aerosmith’s Rocks album in the cassette player of an abandoned truck in a mud hole. He cycled home, tape in hand, played it and never looked back. “I think it was Back In The Saddle that I heard first. The guitar sounds were just massive, and it just tickled my ear. I was like: ‘I like that, I don’t know what they’re doing, but I like that.’”

Religion was a constant presence. Starr was raised a Baptist. He grew up watching his devout father sell horses to the local preacher (“I only ever saw the preacher in a suit with his hair really coiffed, but he came over that day with his truck and horse trailer, and he had his sleeves rolled up, and on his forearm was a tattoo of a dagger, and it said: ‘Born loser’.”).

Around the time of the PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center, an American committee who wanted to limit the access of children to music deemed to have violent, drug-related or sexual themes) hearings, his mother set fire to rock records in their yard. The sort of darkness, contradiction and superstition that seems to get under the skin of anyone from that part of the world, in one way or another.

“I spoke with Alice Cooper twice about this,” Starr muses, “and he pointed it out it was on our Whippoorwill album, Six Ways To Sunday, the imagery in those lyrics about speaking in tongues and handling snakes and all that. It’s very inspiring when you look at it, because it’s all kind of scary.

“That’s another thing about the South, there’s a lot of boogeyman stories,” he continues. “There were all these spooky stories about devil worshippers, and how rock’n’roll bands were causing it. That’s the deeply rooted religious thing, and how people can make it so complicated. It’s such a huge part of the culture.”

Meanwhile in the city of Smyrna, Georgia, near an airbase where their father was a flying instructor (the family had previously lived in the Philippines, among other places, as part of Turner Snr’s military service), the Turner brothers soaked up everything MTV threw at them – “Def Leppard, Judas Priest, Ratt, all that business” – and jammed it out in their basement.

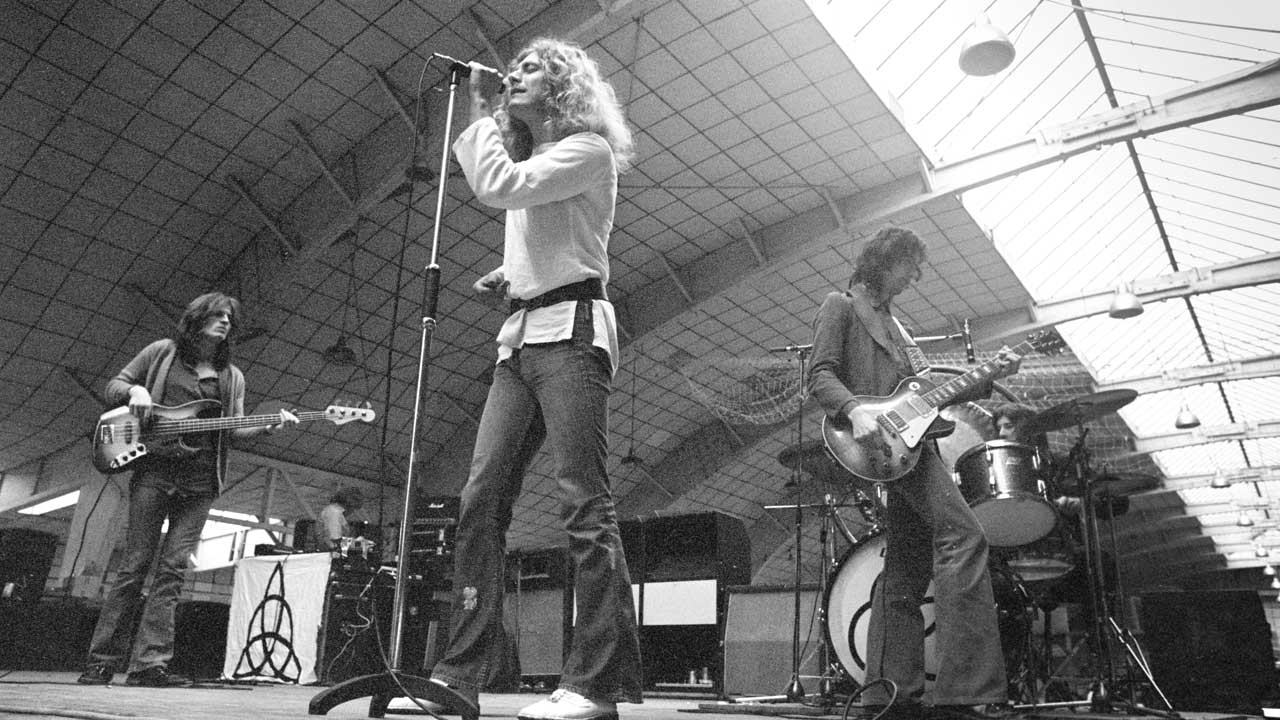

“My dad had some friends from the service, and their kids were a little bit older, so they turned us on to Aerosmith and Judas Priest,” Brit says, “and it went from that to Led Zeppelin. But we went hard into Iron Maiden, then Slayer, Metallica and all that.”

It was AC/DC that set him on the path to being a drummer. “AC/DC was my love because it sounded like: ‘Okay, I understand this, and I think I can play it,” he recalls. “You could never play it like Phil Rudd, but you can play along.”

Inspired, Turner and his bass-playing brother Richard would wind up in Atlanta, playing in local metal band Nihilist. Gigs were full-on, even violent affairs. They opened for Iron Maiden and Metallica, as well as a stream of hardcore groups like Agnostic Front and Circle Jerks. Bad Brains frontman H.R. sat in with them one night.

“That kind of music is more like a sport than the music we play now,” he observes. “It was fun, so we definitely enjoyed it. But it’s a violent kind of music, it’s different. After ten years of slogging it out around this area I really just got tired of it.

Still, in the late 80s/early 90s there was plenty for young musos in America to dig into. Southern-fried rock faces like The Black Crowes, Raging Slab and the Georgia Satellites were enjoying a purple patch, along with heavy misfits like Faith No More and Junkyard; mavericks who filled the space between hair-metal and grunge with underrated aplomb. For Starr, who moved to Atlanta straight after high school, it was an exciting time.

“This was in 1993, and the Black Crowes had exploded. I don’t know if they were responsible for the excitement in the rock scene of Atlanta, but they probably had something to do with it. There were so many bands, and I met so many musicians who are still my friends, and it really excited me. I could barely sleep at night.”

Starr worked in a body shop like his dad by day, playing honky tonks and bars and partying hard by night. “We were in our twenties, so we just went nuts. Some people go to college, I joined bands [laughs]. We drank and did drugs and had a blast.”

And he remembers that quietly fertile, dynamic rock era with fondness. “Even before Nirvana put out the Nevermind record, those bands were already pushing out some of the more bubblegum, hairspray stuff,” he enthuses. “It was like, they look like they haven’t showered in a few days, they’re not just trying to pick up chicks, they’re greasy and real. I was never one for some of the radio-ready, lipstick music. Although I do love the New York Dolls, and Hanoi Rocks.”

Somehow it all led to Buffalo Nickel, the band that Starr and the Turner brothers played in, which, when that fell apart, led to Blackberry Smoke in 2001. But there was/is something about that founding trio that can be felt today in the group’s almost telepathic musical chemistry; the unmistakable warmth; the tight-but-loose ease at heart of everything they do.

A few months ago Starr and the two Turners played together again, as the backing band for a friend making a record down in Macon, Georgia.

“It was kind of like the old days,” Starr recalls, doe-eyed. “It was magical, it made me tear up a bit. There’s something that happens with Brit, Richard and myself. Only the three of us sound like that.”

It all serves to paint a more layered picture of Blackberry Smoke’s world than some may deduce from stereotypes of the American south; simplistic, often damning preconceptions that Starr is all too familiar with, and channels on You Hear Georgia’s title track.

“Hollywood’s always been really good at portraying that,” he sighs. “As I got older and travelled outside of the southern United States… Some of the ways that Southerners can be portrayed in movies – as these wretched, toothless, racist hillbillies – I would meet or see people like that in other places. There’s ugly everywhere, and if people focus on ugly ideas it sort of becomes a stereotype.”

Is it easy for you to separate the South you know, that’s in your music, from the more divided side that has been in the spotlight for the past few years?

“I look at it two different ways, and it really is the good and the bad. I try to surround myself with the good. What the South is to me is completely different to what it is to somebody from California, who’s looking over and thinking: ‘Well, down there it’s all hate and negativity.’ It’s not all good, obviously, I’ve experienced bad things too, but the good outweighs the bad for me. A lot of people just can’t move past horrible, horrible things. And I’m not saying that it’s easy…” Starr pauses, thinking. “I don’t know, that’s a deep subject.”

In a sense his lack of outspoken politics – except those that may hide behind his calm, kind eyes – says a lot about Blackberry Smoke, a band who’ve created a safe space of sorts, where differences and nuance are accepted, even expected, without fuss. Where the appeal of the music is simple, and deep if you care to listen for it.

“The music is, in its way, sacred to me, it’s not just a commodity,” Starr says. “It’s rock’n’roll. It’s meant to make you feel good, it’s not to be feared.”

Polly is deputy editor at Classic Rock magazine, where she writes and commissions regular pieces and longer reads (including new band coverage), and has interviewed rock's biggest and newest names. She also contributes to Louder, Prog and Metal Hammer and talks about songs on the 20 Minute Club podcast. Elsewhere she's had work published in The Musician, delicious. magazine and others, and written biographies for various album campaigns. In a previous life as a women's magazine junior she interviewed Tracey Emin and Lily James – and wangled Rival Sons into the arts pages. In her spare time she writes fiction and cooks.